VOL. 13, No. 2, 1-32

This case study of a university-level course delivered by computer conferencing examined student participation and critical thinking. It was guided by two purposes: (a) to determine whether the students were actively participating, building on each other's contributions, and thinking critically about the discussion topics; and (b) to determine what factors affected student participation and critical thinking. The results suggest that the emergence of a dynamic and interactive educational process that facilitates critical thinking is contingent on several factors: appropriate course design, instructor interventions, content, and students' characteristics. The study concludes that computer conferencing should be given serious consideration by distance educators as a way of facilitating interaction and critical thinking in distance education and overcoming some of the limitations of correspondence-style distance education.

Cette étude de cas, qui avait pour objet un cours universitaire diffusé par téléconference informatisée, s'est penchée sur la participation et l'esprit critique des étudiants. Son objectif était double : (a) établir si les étudiants participaient activement en mettant à profit les contributions de leurs co-apprenants et en montrant un esprit critique face aux sujets de discussion; et (b) identifier quels facteurs influaient sur la participation et l'esprit critique. Les résultats proposent que l'émergence d'un processus éducatif dynamique et interactif propice à l'esprit critique dépend de plusieurs facteurs : une conception de cours appropriée, les interventions du formateur, le contenu et les caractéristiques des étudiants. L'étude conclut que la téléconférence informatisée mérite que les formateurs à distance s'y intéressent sérieusement, car elle peut être un moyen de promouvoir l'interaction et l'esprit critique, de même qu'un moyen de vaincre certaines limites qu'impose le modèle d'éducation a distance du type "cours par correspondance".

Despite the growth in the size and acceptance of distance education, there have been persistent criticisms of this form of educational delivery because it often fails to provide for interaction among students and between students and instructors. Without this, it is suggested, distance education can only be an inferior imitation of the best face-to-face education because learners are unable to clarify and challenge assumptions and to construct meaning through dialogue (Henri & Kaye, 1993; Lauzon, 1992).

According to Lauzon (1992), the challenge for distance educators is to “search out means of reducing structure and increasing dialogue so that learners may move from being simply recipients of knowledge to actively embracing and working with objective knowledge to make it their own” (p. 34). In effect, the critics argue, much distance education is rooted in a transmission model of learning that inhibits the development of critical thinking. Learners passively assimilate knowledge rather than critically examine and construct it, based on their own experiences and previous knowledge (Burge, 1988; Garrison, 1993; Lauzon, 1992).

Some critics believe distance education’s inability to reproduce a critical dialogue among students and between students and instructor can be addressed through the use of two-way communication technologies. These provide opportunities for interaction that, it is suggested, lead to reflection and deeper understanding (Laurillard, 1993). Audio- and videoconferencing are used to achieve this, but these are time- and place-bound technologies that require all learners in a course to be available at the same time and to travel to one of several meeting places. A more flexible alternative involves using text-based, asynchronous (i.e., not in real time) computer conferencing to create a more interactive form of distance education that still retains the flexibility of time- and place-independence. Appropriately designed computer conferencing, it is argued, will facilitate interaction among students and between the instructor and students, thus making distance education more appropriate for the higher-level cognitive goals of college and university education (Harasim, Hiltz, Teles, & Turoff, 1995; Lauzon, 1992; Tuckey, 1993).

Computer conferencing is a relatively new educational technology that has been used for higher education instruction on a small but growing scale since 1982 (Feenberg, 1987). It is a subset of computer-mediated communications involving a configuration of computer hardware and software that allows group members to share information with each other. Until recently this information was text-based only, and this is still the most common type of computer conferencing, but the technology now allows for the exchange of multimedia information as well. This study examined a text-based computer conferencing system. Computer conferencing systems are “designed to facilitate collaboration among all sizes of groups, from two-person dialogues to conferences with hundreds or thousands of participants” (Harasim, 1993b). All messages to a conference are organized and stored sequentially. Depending on the software, messages can be sorted and reorganized according to different criteria such as date, author, subject, key words, or topic. Some systems provide message threading that links messages on the same topic.

The literature on educational computer conferencing is replete with references to its potential to create a new learning environment in which interaction, collaboration, knowledge building, and critical thinking are the defining features (Harasim et al., 1995; Hiltz, 1994; Mason & Kaye, 1990; Riel & Harasim, 1994). Harasim (1994) suggests that computer networking in education is a new paradigm that she calls network learning, a unique combination of place-independent and asynchronous interaction among learners connected by computer networks that will result in new educational approaches and learning outcomes.

There is limited empirical support, however, for the claims made about the potential of computer conferencing to facilitate higher level thinking. In 1987 Harasim reported, “We understand little about the new phenomenon of learning in an electronic space. There is as yet little data describing or analyzing teaching and learning within this asynchronous, text-based (screen) environment” (Harasim, 1987a, p. 119). More data are available now, but as recently as 1994 Burge suggested there was still a scarcity of qualitative studies that enabled researchers to “develop new and relevant concepts and hypotheses for consequent explorations” (p. 22). Eastmond (1994) also suggests there is a need for more studies that examine online learning from the student’s perspective.

Little is known about how and why learners participate in computer conferencing and what factors may affect their participation. Similarly, there has been little empirical study of the quality of computer conferencing interaction. Mason (1989) observes, “Many laudable studies have been carried out based on the user statistics generated from conferencing applications ... However, one usually looks in vain for any relation between this kind of analysis and an evaluation of the actual content of messages. In fact most computer conferencing literature distinctly avoids making anything but very general statements about the content of messages” (p. 97).

A further limitation of the computer conferencing research is that much of the seminal work focused on the participation of graduate students, academics, and professionals, but these studies did not attempt to analyze the educational quality of student participation or the factors that may influence it (Hiltz, 1990; Lauzon, 1992).

This study investigated a university-level undergraduate course that was offered through computer conferencing. It was guided by two main questions: (a) to what degree did students actively participate, build on each other’s contributions, and think critically about the discussion topics? and (b) what factors affected student participation in the course, and did they influence participation?

A review of the literature revealed three categories of factors that combine to affect learner participation: the attributes of computer conferencing, the design and facilitation of computer conferencing activities, and student situational and dispositional factors.

Harasim (1990) suggests the attributes of communication via computer conferencing are: many-to-many communication; place-independent group communication; time-independent group communication; text-based nature of communication; and computer-mediated learning.

The literature suggests that some or all of these attributes can promote or discourage participation (Burge, 1994; Feenberg, 1987; Harasim et al., 1995). This study attempted to determine under what conditions these attributes might facilitate or encourage participation and their relationship to the other factors in the conceptual framework.

The second category of factors that can affect participation is the design of the conference activities. The literature suggests that the interactive potential of computer conferencing will not be realized unless designs are employed that require learners to respond and contribute to discussions and that require instructors to play a facilitative rather than a directive role. That is, the activities should be designed to elicit inter-student communication and collaboration as well as student-instructor interaction (Berge, 1995; Davie & Wells, 1991; Harasim et al., 1995; Rohfeld & Hiemstra, 1995). This study examined how the conference activities were designed and facilitated and how students responded to these factors in an attempt to understand the impact of these factors on student participation.

The literature is less clear about learner factors that may hinder or facilitate participation. Dispositional factors include: the predisposing attitudes of the learner toward computer conferencing, distance education, education or the subject matter; computer skills in general and the more specific skills required to use the computer conferencing system; comfort with the medium of communication; the degree to which the learner is comfortable with the epistemological orientation of the course and the learning activities; and the motivational orientation of the student.

Situational factors include student access to the necessary computer hardware and software, their home situation in general (i.e., is it supportive of home study?) and amount of time available for study.

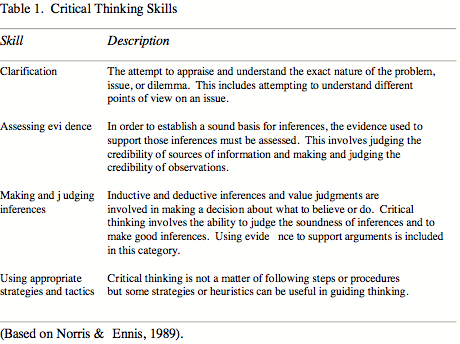

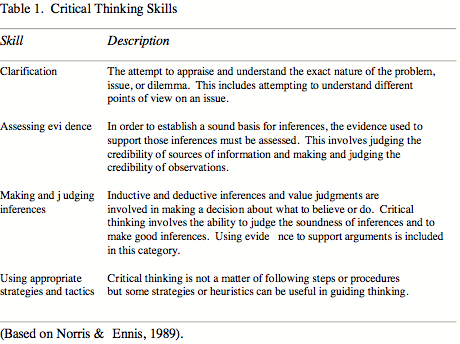

Critical thinking was defined as thinking that is reasonable and reflective and focused on what to believe or do (Norris & Ennis, 1989). Four categories of critical thinking skills were identified based on Norris and Ennis’ (1989) and Ennis’ (1987) definition and model of critical thinking, as well as the work of Quellmalz (1987) and Bailin, Case, Coombs, and Daniels (1993). Table 1 contains the four categories of thinking skills used in this study.

The study was carried out at the University College of the Fraser Valley in Abbotsford, British Columbia using one section of the course, Computer Information Systems 360 (Information Systems in Organizations and Society), which ran from January to April 1996. This was a required course in the college’s Bachelor of Computer Information Systems. It examined issues related the uses of information systems including legal, ethical, and privacy issues and the impact of automation on organizations and society (Instructor, 1996). Eighteen students registered for the course, and 13 completed it by writing the final examination. Two students dropped out before logging on.

A case study approach that involved the collection and analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data was used in this study (Yin, 1994). This complementary approach was chosen because the study sought to describe and analyze both the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of participation in computer conference discussions and to understand learner and instructor perceptions of the factors that affected their participation (Shulman, 1988).

The quantitative data collected for this study consisted of the number of messages posted by each student, the frequency of participation, the number of intermessage references, and an assessment of the degree to which students appeared to be thinking critically while participating.

Intermessage analysis followed Levin, Kim, and Riel’s (1990) technique of intermessage reference analysis whereby each message is analyzed to determine whether it refers to any other messages. The content of all the messages in the computer conferences was analyzed for evidence of the use of critical thinking skills (positive indicators), and also for evidence of uncritical thinking (negative indicators). Looking for evidence of uncritical thinking provided a balanced picture of each student’s level of critical thinking because it is assumed that the ratio of critical to uncritical thinking will vary from student to student. This is one of the factors that was used to determine each student’s level of critical thinking. A detailed description of the content analysis procedure is contained in Bullen (1997).

Transcripts of each conference were read and marked up for positive and negative indicators of the critical thinking skills in Table 1. Once the transcripts were marked, the students were sorted into one of three categories of critical thinking and assigned a corresponding score for each conference. The categories and corresponding scores were as follows: High (3)—extensive use of critical thinking skills, minimal use of uncritical thinking; Medium (2)—moderate use of critical thinking skills, some uncritical thinking; and Low (1)—minimal use of critical thinking skills, frequent use of uncritical thinking. Categorizing the contributions in this way was a subjective process, but detailed operational definitions of the three categories were used to guide the process (Bullen, 1997). In addition, the content analysis was guided by the overall definition of critical thinking adopted for this study: thinking that is reasonable and reflective and focused on what to believe or do (Norris & Ennis, 1989). In analyzing student contributions, then, the criteria of reasonableness, reflection, and focus on beliefs or actions were always applied regardless of the individual critical thinking skills identified.

The qualitative data consisted of the perceptions of the learners about their participation and use of critical thinking and the perceptions of the instructor about these factors. These were gathered using in-depth, semi-structured interviews with the instructor and 13 of the 16 students. The major themes from the literature provided the organizing framework for the interview schedule (Appendix A). and data were analyzed using the major categories. The definition of critical thinking was used as a basis for analyzing student responses to the question dealing with their understanding of the concept.

The students enrolled in this third-year university-level course were mostly male (15/18), in their early to mid-20s, studying full time while working part time. Although they were experienced computer-users, only one had any previous experience with computer conferencing or online education, and only two had any previous distance education experience. All of the students were taking the rest of their courses on campus.

On average, the 13 completing students posted 15.92 messages during the 14 weeks of the course for a weekly average of just over one (1.14) messages per student. Compared with the findings of other research this is a low-to-moderate participation level. Studies by Harasim (1993a), for example, found student participation levels ranging from an average of 5 messages per student per week to a high of 10, in 12 different undergraduate and graduate courses.

The small population size and homogeneity of the students precluded the use of statistical tests of association between student characteristics and participation levels, but possible relationships were observed between gender, reasons for taking the course, educational level, age, and participation. The three women in the course contributed more messages and had a higher average critical thinking score than the 10 men. The students who indicated that one of the reasons they took the course was because it was offered online contributed more messages and had a higher mean critical thinking score than those who did not indicate this was a reason. The students with some previous postsecondary education contributed more messages than those with only a high school education, and older students contributed more messages than younger students.

The instructor used computer conferencing for two main purposes: to deliver a “lecture” that supplemented the course textbook and readings by providing the instructor’s interpretations and elaboration of the reading material; and to conduct seminar discussions on key course issues. The course was organized around a series of readings and 12 related online discussions. Every two weeks for the first 10 weeks of the course, there were two concurrent online conferences related to articles or textbook chapters the students were to have read. One of the two concurrent conferences presented an ethical scenario that students had to consider and then decide whether the activity in question was ethical, unethical, or not an ethics issue. Students were instructed to support their position with reasons. In the other concurrent conference, the instructor presented one or more discussion questions that were related to that week’s readings and that had ethical implications. Students were instructed to answer the questions by thinking critically about the issues involved and then presenting a well-reasoned and supported argument on one side of the issue. The instructor used the same definition of critical thinking adopted by this study (Norris & Ennis, 1989). For the last three weeks of the course there were two consecutive discussions that overlapped slightly. The instructor’s purpose in using seminars was to encourage students to interact with each other in order to think critically about the issues and to relate them to their own experiences.

Participation in the online conferences counted for 15% of the final grade. In addition there were mid-term (20%) and final examinations (20%), an essay (15%), and a term paper (30%). The instructor tried several approaches to promote and encourage online discussion. He began by posing the questions and asking students to present well-supported and well-argued responses. In subsequent discussions his instructions became more specific; he tried to promote greater inter-student discussion by organizing collaborative learning activities and by breaking the class up into dyads.

In general the instructor used a dialogical style of teaching, as opposed to a didactic or fact-based questioning style, which is recommended for facilitating critical thinking (Sternberg & Martin, 1988). Although he did present electronic lectures or “electures” in which he discussed the readings relevant to the week’s discussion topic, these were brief and made up only 10% of his messages (7 of 72). Instead, his style was to monitor the discussions and respond selectively to students’ comments, with encouragement, clarification, redirection, and summaries.

In total the instructor contributed 72 messages to the 12 discussions, ranging from a high of 19 messages to a low of one message. The instructor’s participation tended to be clustered on a few days in each conference instead of evenly distributed throughout the conferences. Of the 86 days between January 15 and April 9 the instructor posted messages on 20 of them for an average contribution rate of once every 3.47 days. However, his frequency of posting ranged from daily on eight occasions, to a gap of 13 days on two occasions. There was also one gap of 10 days, one of eight days, one of five, two of four, two of three days, and one of two days.

Despite his experimentation with several ways of organizing the online activities, in general the instructor played a relatively passive role in the course. Once he initiated the discussions with the opening question or issue, he remained silent and contributed only occasionally.

Henri (1989, 1992) identifies two types of messages: independent and interactive. Independent messages deal with the topic of discussion, but make no implicit or explicit reference to any other messages. Interactive messages deal with the topic, but also refer to other messages by responding to them, elaborating on them, or building on them in some fashion. Only 48 of the 207 (23%) messages were classified as interactive.

Content analysis revealed that all students appeared to be thinking critically at some level about the issues raised for discussion. Critical thinking scores were averaged across the 12 conferences. Individual mean scores for the course varied from 1.2 to 2.6. The overall mean critical thinking score was 1.83. According to the criteria established for the analysis, a score of 1 corresponds to the low category, 2 to the medium category, and 3 to the high category. All students in this class received mean scores higher than 1, and in all except two cases they were 1.5 or higher. However, only three of the 13 students received scores higher than 2. This suggests that although all students were thinking critically to some degree, none was doing so at the highest levels on a consistent basis.

Critical thinking levels also varied considerably from conference to conference, and there does not appear to have been any consistent trend over the duration of the course.

Critical thinking tended to be highest at the beginning and end of the course and lower in the middle weeks.

The factors most frequently and consistently identified by students as either facilitating or inhibiting their participation and critical thinking in online discussions were those related to the attributes of computer conferencing technology.

Time-independence. Time-independence in particular was mentioned by all students as having either, or both, positive and negative impacts. In the literature, the time-independent nature of computer conferencing is often cited as a positive feature because it enhances student control over the time of interaction, thus facilitating self-directed learning (Harasim, 1990). For most of the students in this course, however, it was a double-edged sword: it facilitated their participation and critical thinking but exacerbated their difficulty in managing their time effectively. Student #6:

I think the most, the worst thing about the course was because it was online it doesn’t seem like a real course. It was like I have four courses plus this online course which isn’t a real course anyway and because I spend a lot more time with my real courses than I felt I should have I didn’t put aside the time that might be suggested ... but it was also helpful that it was something you could do at three in the morning if you wanted to, so you weren’t really restricted by the fact that you were hungry or thirsty or tired or whatever, you could do what you want when you want which was both a help and a hindrance I think. (6:1:1)

Two other themes that emerged related to the time-independent attribute were the ability to be reflective and to compose thoughtful rather than spontaneous responses, and the democratizing effect that prevented discussions from being dominated by a few articulate or verbose speakers.

On the negative side, however, for some students there was also a sense that the inherent delays in asynchronous communication militate against the development of a dynamic and interactive online discussion, that this form of communication was not real, that it did not adequately simulate a face-to-face discussion, and that it left them feeling remote, detached, and isolated, and this discouraged them from participating. Student #15:

When you’re sitting there alone in your little office in front of your computer, it feels like you’re all alone and you can type anything you want and nobody is going to say anything because it feels like you’re completely alone, plus I think the pace at which discussions progress, well the fact that you’re not facing anybody, you don’t have to take immediate responsibility for what you said. (15:9:1)

In a sense ... it’s kind of like a situation where you’re required to submit a sealed bid in an auction or something. You know, you do your best, give it the best that you think you can but you don’t really know what the response is until much later. (15:9:2)

For these students the bulletin board metaphor, rather than a conference or discussion metaphor, was a more accurate description of the online activity. They were unable to perceive the individual messages as part of a discussion and thus their ability to respond critically was hampered because for them there was no real discussion. It also seemed important for these students to have their ideas validated, either by the instructor or by other students. Although the instructor did try to provide encouragement and redirection, he did not do it consistently, and students rarely followed up each others’ messages.

Whether students found the time-independence facilitated or hindered their participation, all expressed a desire for some form of real-time communication, whether face-to-face or by computer, audio-, or videoconferencing. The reasons given for this varied. Some preferred real-time communication. Others said they needed the structure of regular meetings to force them to devote time to the course. For those who were generally comfortable with the asynchronous environment, the real-time component was seen as a way of getting more immediate feedback from the instructor and for compensating for perceived deficiencies of the text-based environment. In particular they felt that if they could see and/or hear their fellow students, they might get to know them a little better and that this would improve the subsequent asynchronous discussions.

Text-based communication. The text-based attribute of computer conferencing was another commonly mentioned factor that was perceived to have had an impact on student participation. Students were almost evenly divided over whether the attribute had positive or negative impacts. In some cases the perceived impact of the text-based attribute was similar to, or the same as, some of the impacts of the time-independence attribute: it created a sense of detachment and a feeling of anonymity, but in this case it was brought about by the lack of visual and auditory cues and the reliance on textual communication. For some students the lack of facial expressions and voice intonation made computer conferencing a less human form of communication. For these students there was no “virtual community.” The online activity was not an interactive discussion, but just a series of messages posted to an electronic bulletin board. They felt no connection with their fellow students and thus felt no compulsion to go beyond the minimum participation required.

As with time-independence, the textual environment was not always viewed negatively. For some students it had a liberating effect, allowing them to compose their contributions, reread them, and possibly revise them before posting, thus facilitating a more reflective and critical approach.

Computer-mediated communication. One attribute of computer-mediated communication mentioned by the students was the random access to a permanent record of conference discussions. For some this feature was viewed positively as enhancing their participation by allowing them to read selectively and reread and review when necessary. Student #6, for instance, found this to be “more orderly, easier to follow the way things were going” than in a classroom (6:3:1). Student #1 found this attribute eased him into the course because he “could get the gist of that class without doing every page of reading” (1:4:1). However, the extent to which this translated into active participation or critical thinking is questionable because he went on to say, “You could get the idea of what’s going on even if you didn’t participate in the discussions but read other people’s discussions” (1:4:2). For some, then, it is possible that although having random access to the record of discussions may have facilitated their initial participation, it may also have served to discourage more active participation because they were able access all the information they felt they needed by reading other contributions.

A negative manifestation of the permanent record experienced by some students was information overload. As the course progressed the record got longer and longer and the ability to deal with it became more of a problem for these students, particularly those who did not have the self-discipline to log on regularly.

The public nature of the permanent record also had an inhibiting effect on the participation of a few students. These students found it disconcerting to look back at some comments they had made early in the course or in the heat of the moment.

Software and interface design features were other aspects of the computer-mediated nature of computer conferencing that students mentioned as influencing their participation. The computer conferencing software used in this course (First Class) required students to participate “on-line”; there was no “off-line” capability. Because nearly all students were connecting from home, it meant tying up the phone line during this process. This forced some to hurry their online participation and tended to negate some of the benefits of time-independence such as having time to reflect and to compose and edit contributions.

Many-to-many communication. Some students indicated that they appreciated the potential that many-to-many communication offered. The access to other students’ ideas and opinions, the fact that everybody had equal access to the “floor,” and the importance of feedback and interaction were cited by students as positive impacts.

Although the ability to engage in many-to-many communication was viewed positively by students and may have affected the quality of student participation, it is not clear if it had any facilitating or inhibiting effects. Students did not indicate they participated more because of this aspect or that they found it easier or felt more motivated to participate. Rather, it was seen as having a positive impact on the type and quality of participation.

Interestingly, only two students mentioned that it had a positive impact on their ability to think critically. They felt the online discussions allowed them to consider multiple perspectives on the issues and to refine and revise their ideas based on feedback and from reading the contributions of other students and the instructor.

Mandatory participation seems to have had some unintended side effects. For some students the marks associated with mandatory participation did not necessarily result in more participation. Instead the marks became part of an ongoing type of cost-benefit analysis that they engaged in to determine how to apportion their time. Other students responded to the marks for participation, but not necessarily with enthusiasm. They explained that often what they had to say was not particularly original or insightful, but they wanted to get the marks. They felt they were often simply restating what had been said already by other students.

The need for social activities, pacing, and the instructor’s participation were three other themes that emerged related to the course design. Some students said that social activities would allow them to get to know each other before they began the discussions. This was partly behind the almost unanimous desire for some form of real-time communication discussed above. Students felt they needed this form of communication in order to develop a social bond and that some sort of social cohesion was a prerequisite to meaningful discussions of the course content.

In campus-based education, regular classes serve a pacing function that helps to keep students focused and on-task. Distance education completion rates increase significantly if substitute forms of pacing are used (DeGoede & Hoksbergen, 1978). In this course, pacing was achieved mainly by having regular online discussions with clear beginning and ending dates and specific deadlines by which students were required to contribute.

Students perceived that these pacing measures were only partly successful and that they may have had some unintended impacts on participation. There was a sense the discussion was stunted by the combination of the deadlines and the limited time frames for the discussions because students waited until the deadline to contribute, which then left no time for follow-up comments or responses.

They also said they were generally pleased with the instructor’s participation, but five did indicate that more instructor involvement in the discussions might have stimulated further student involvement and helped generate deeper discussions, yet in the end students assessed this course as more interactive, participatory, and interesting than many of their other courses.

The student’s study environment is a crucial factor for success because it plays a much larger role in the learning of the distance education student than it does for students attending campus-based classes. In this course most of the students were participating from their homes. However, all were also attending other classes on-campus, so the home study environment may have been less important than it would be for full-time distance education students.

Another factor that was mentioned related to the non-distance nature of most of the students in this course. Student #16 indicated that he often met face-to-face with some of the other students in the class, and they sometimes discussed some of questions that were meant to be discussed online. Later the results of these discussions would end up in the online discussion. For this student this was a positive impact because he felt he had to establish some connection with his fellow students before he could participate effectively. But for others this made the online discussions feel somewhat artificial.

Time available for study and participation was also an issue for most students. Nearly all the students were studying full time and working part time; some were even studying and working full time, and some had other extracurricular activities that competed with the time available for studies.

Learning style preferences and personality may help to explain why some students feel comfortable in the online environment almost immediately, whereas others struggle with it and in some cases never accept it. Three students indicated a clear preference for face-to-face classes, and all but one felt that their participation would have been enhanced if there had been some type of real-time discussion. They had difficulty with the asynchronous nature of the communication and the lack of visual and verbal cues.

On the other hand, three students who described themselves as shy or introverted and said they had difficulty participating in campus-based classes found the online environment liberating because it allowed them time to contribute, free from the competition of more verbally adept students.

Another learning style-related issue that emerged was a preference or need for more teacher direction. The learning environment of this course presented a challenge for these students because its design meant it was essentially an independent study course that lacked strong teacher direction and that, therefore, required self-discipline and effective time management. Most students felt they were not prepared for the self-discipline that was required by the course, and two students attributed their decision to drop out of the course to their inability to deal with this.

In general the students had an incomplete understanding of the concept of critical thinking that did not conform to the definition used by the instructor in this study. None cited skill in all four categories, and only four of the students mentioned skills in three categories.

Related to the students’ understanding of critical thinking are their perceptions of the purpose of the online activity and what they were expected to do online. Again, most students had an incomplete understanding of this element of the course. Student responses were analyzed for an indication that they understood the basic quantitative requirements of online participation (regular logging on, minimum of three messages per week related to the current topic) and that the purpose of the discussions was to facilitate their critical thinking about the issues. All students understood the quantitative requirements, but only two were able to articulate clearly the purpose of the discussions. Five seemed to have a partial understanding, and four seemed completely to misunderstand the purpose.

The instructor felt that the discussions were not very interactive and that most students were making independent comments that did not relate to, or build on, comments made by other students. However, he felt the students demonstrated a good grasp of the issues presented for discussion, and he was generally satisfied with the level of participation and the use of critical thinking in the discussions. He conceded that the discussions did not reach the same level of intensity as the last time the course was offered online, but he felt, given the generally passive nature of the students and their experience with a predominantly didactic style of teaching, that they performed well in this class.

The instructor cited the asynchronous nature of the communication and the design of the software as having an impact on students’ feeling of inclusion, which in turn may have affected their participation.

He believed that students liked the convenience of asynchronicity, of being able to participate when it suited them and not at a predetermined time, but they would have liked others, especially the instructor, to respond to their contributions in a more timely manner. The instructor felt that his inability to respond to this asynchronous/immediacy dilemma may have resulted in some students not participating as intensively as they might have had he been able to respond more quickly.

The instructor’s view on the importance of rapid responses is supported by Tagg and Dickinson’s (1995) study, which found that frequent and prompt responses that offer guidance to students encourage student participation.

The design of the First Class computer conferencing software was also seen by the instructor as possibly having an impact on students’ feeling of inclusion and, consequently, their participation. He raised two issues: the impersonal nature of how the messages are handled and the passive nature of the interface.

When a message is posted to a conference in response to another message, the response is only posted in the conference. The author of the original message does not know that anybody has responded to his or her message unless he or she checks the conference. In some other conferencing systems, when responses are made they are posted in the conference as well being sent to the original author’s e-mail address. In this way the original author gets personal notification that somebody has responded to her or his message.

The other aspect of the software that was mentioned by the instructor was the fact that all messages in all conferences are always shown, and the only distinction between those that have been read and those that have not is a small red flag. Furthermore, each conference folder has to be opened to find out if there are any new messages. Other conference systems with a more active interface provide a “new-message” alert on the desktop and can be configured to show only the unread messages. The passive nature of the interface was mentioned by only one student, but it should not be ruled out as having a wider impact on that basis. People are often not aware of why they react in particular ways to technology, and it is possible that other students may have also been affected by this feature.

The instructor attributed the lack of sustained discussion, in part, to the absence of substantial differences of opinion on most of the issues. Most students offered similar points of view, and when there were differences they were stated mildly. In his view students seemed to be overly concerned about offending the instructor or other students. In retrospect he felt he might have been able to stimulate some discussion if he had taken a more active role, challenging students to elaborate their positions and to compare them with those of other students, but he felt somewhat removed from the course because he was reusing material from the previous year.

The concentration of activity in the final few days of each conference was seen as a deterrent to ongoing discussion because there was not enough time left for students to respond to each other’s contributions. The instructor had hoped and expected that students would log on regularly, that is, every day or two, but this did not happen.

The instructor identified several student characteristics that he felt had an impact on participation. He saw the students as not motivated to participate and believed they viewed their education as a necessary evil, not something in which they had any inherent interest. Looked at in terms of motivational orientation, if the instructor’s assessment is accurate, most of these students would be considered goal-oriented (Houle, 1961). That is, they were enrolled in this program with a clear objective in mind: to get the necessary qualification to obtain a job in the information systems business. In addition, this was the only course in their program that did not have a technical and instrumental focus, which may have influenced students’ motivation.

An issue identified by the instructor that may have been related to the lack of motivation was lack of time. The instructor felt that most students were pressed for time because of their part-time jobs and full course loads. According to the instructor, most of the students were working at part-time jobs for at least 15 hours a week, with many working more than 20 hours per week. Lack of time also emerged as a theme in the student interviews. What surprised the instructor about the time issue is that the students did not seem to consider the possibility of reducing their work commitments.

The instructor also identified passivity as a characteristic of many of the students that tended to inhibit their participation. Based on his previous experience teaching in the Computer Information Systems program, he said he found students were generally reluctant to initiate discussion. Discussion, dialogue, and group work are not commonly used instructional techniques in this program.

The results indicate that although all students contributed to the online discussions and all appeared to be using at least a minimal level of critical thinking, this course was not an example of the new paradigm of online learning that is mentioned in the literature. However, in the view of many of the students and the instructor, it was a more interactive, participatory, interesting, and engaging learning experience than many face-to-face courses they had taken previously. Why was this, and why did the course not measure up to some of the descriptions of computer conferencing as a virtual community of inquiry? Why was there a generally higher level and quality of online participation than the instructor was used to getting in the face-to-face classes he taught? Conversely, why were there not greater levels of participation and much deeper, more interactive, and sustained discussions?

Relative to the results of other research, the participation levels and interactivity in this course were considered to be low or moderate (Bullen & Salinas, 1998; Davie, 1988; Harasim, 1987a, 1987b, 1993a; Hansen et al., 1991; Henri, 1992). Other research found cost of access, technical problems, and lack of experience with computers to be barriers, but these issues do not appear to have been factors in the low levels of participation and interactivity in this course, as these students were all experienced computer users and most had ready access to a computer (Hansen et al., 1991; Hiltz, 1997; Mason, 1989).

A number of factors should have helped to increase participation in this course: 15% of the course grade was assigned to online participation, the course content lent itself to discussion, and the instructor followed many of the recommendations for effective online teaching. The results of this study clearly indicate, however, that this was not enough to foster active participation in the course and that the ability to participate in a course using computer conferencing is affected by a number of factors. Several related factors appear to have been particularly relevant in this.

Most of these students were in their early to mid-20s and in their second or third year of college, with a few having come directly from high school. Only one of the completing students had any previous distance education experience. According to the instructor, these students were accustomed to what Sternberg (1987) describes as the didactic approach to teaching in which the instructor lectures, the students listen and take notes, and there is limited student interaction with the instructor and/or other students during class. Furthermore, they were enrolled in a technically oriented degree program that consisted primarily of courses dealing with computer programming, information systems management, and other technical subjects. This was the only required course in the program that, in both its face-to-face and online versions, resembled a social sciences or humanities course in which there were discussions and the consideration of multiple perspectives on complex social issues. In the words of Paul (1993), this was multilogical subject matter, not the monological content of most of the other courses these students were taking, in which correct procedures were learned and applied. In short, these students were used to sitting and listening, used to learning the correct way to do things in the world of information systems and applying this knowledge in different contexts. For many of these students, the extent of their participation was showing up in class on a regular basis. They were not used to discussing controversial ethical issues with their fellow students and instructors, and they were not used to being able to determine when, where, and how they would participate in class. Student #6 summed up the perspective of these students:

Most people have gone through school, they get up in the morning, they go to school, they sit down at a desk, and they come home, and this was something I’d never experienced before, this online class, so it was different and in that way it seemed almost like it wasn’t an actual course because there was no class time or no assigned class time. There was no sitting down at a desk and listening to a teacher talk. That’s why I think of it as a fake course. (6:1:3)

This online course placed tremendous demands on these students. Accustomed to the security of the classroom environment where their presence was their participation, they suddenly found themselves in a situation where they were required to participate actively by making written contributions to discussions, where they were given the freedom to choose when to participate, from where, how frequently, and how substantially. Although the instructor’s expectations were laid out clearly in the course outline, the interviews with the students indicate that most only had a vague idea of what an online course was and what they were expected to do.

Compounding the effect of this inexperience with distance education, a dialogical teaching style, and multilogical subject matter was the fact that this was their only distance education course, the only course that was time- and place-independent, and that did not require the students to attend classes on a regular basis. The rest of their program consisted of face-to-face classes. Ironically, several students took this course because of the flexibility it afforded, yet as the interviews revealed, many could not handle the self-discipline and time-management that was required to integrate this course successfully into the rest of their program. This is consistent with the results of Hiltz (1994) and Simich-Dudgeon (1998) who found that self-discipline, self-direction, and good organizational skills were key factors in student success in an online environment.

For these students the idea of the virtual classroom was too abstract and required too much self-directed cognitive engagement. Time and place-independence became unmanageable responsibilities rather than features that facilitated access and participation. In setting their priorities, it was only natural for these students to deal first with the things that demanded their attention such as the presence of an instructor or attendance at a lecture. The online class may be open 24 hours, but students may rarely venture in if attendance is entirely up to their discretion.

The face-to-face context in which all of these students were taking this distance education course may have had another impact. Distance education has traditionally been employed to provide access to students who cannot make it to campus. In this context, all the students were attending the college campus for their other courses, and some were seeing each other on a daily basis. This made the online discussions seem somewhat artificial for some students and so may have hindered their online participation.

So although in theory the time- and place-independence of this course should have given students greater flexibility of access and thus facilitated their participation, in practice it ended up acting as a barrier to the participation of some students because they participated from home, in the evening, and then often only after they had completed other studying and assignments.

There is an implicit assumption in much of the literature on computer conferencing that, for many educational purposes, this form of asynchronous, mainly text-based communication is in many ways superior to synchronous and face-to-face forms of communication. However, it is important to remember that for most people it is an unfamiliar form of communication and that, regardless of how great its potential advantages for facilitating or encouraging interaction, people must adjust to its peculiarities before they become comfortable with it (Hill, 1997). This lack of familiarity may explain the almost unanimous desire expressed by the students for some form of synchronous communication. With the exception of an introductory orientation session and the final examination, all learning activities in this course were handled through computer conferencing. Although all of the students were experienced computer users, familiar with e-mail and the Internet, only one had any previous experience with an online course. The underlying theme in their comments seemed to be that, regardless of their willingness to engage in this new form of communication, it was still in a sense a second language for them. Some seemed to be more fluent than others, but most missed the familiarity of synchronous communication. Feenberg (1987) calls this communication anxiety, the feeling of detachment, of not being sure who is really out there, when to expect a response, and what kind of response that will be.

The literature on computer conferencing suggests that students who find it difficult to participate in face-to-face learning environments because of shyness or a preference for written communication will find computer conferencing a more comfortable learning environment because it is text-based and they are able to participate without having to compete with others to be heard. They will also have as much time as needed to formulate their thoughts (Harasim, 1990). The results of this study generally support that view, but not unequivocally. Several students who indicated they found participating in classroom environments difficult said they felt more comfortable using computer conferencing, and this may explain in part why most students and the instructor felt there was greater student participation in this class than in similar face-to-face classes and in the same course offered face-to-face. However, the experience and perceptions of one student indicate that there may be exceptions to the rule that computer conferencing is an ideal environment for students who have difficulty participating in a classroom. Student #15, who said he was an introvert, found the need for what he called “constant contact” overwhelming. It did not seem to matter to him that the contact was asynchronous and text-based, nor that, beyond the minimum requirement, participation was voluntary. In order to stay on top of the discussions, he perceived a need to log in regularly and to make regular contributions. For him this was constant contact and he found it taxing. However, he also admitted to being unable to deal with the self-discipline and self-direction required of this distance education course, so isolating the impact of these two factors is difficult. Did he find the course taxing because of his personality or because he was accustomed to a much more teacher-directed environment? In this student’s view both played a part in his decision to drop out of the course after six weeks. His personality was not compatible with what he perceived to be the constant contact that the course required, and his preferred style of learning was not compatible with the self-discipline and self-direction required. This student’s experience indicates that the relationship between personality and comfort with this medium may not be as obvious as some of the literature may indicate.

The instructor’s approach to, and his perceptions of, his role in organizing and moderating the discussions may also have had an impact on student participation. The literature indicates that the role of the instructor in computer conferencing environments is crucial to the success of the course. In order to promote and encourage student participation, the instructor has to ensure that she or he does not become the center of attention, the authority that students look to for the “correct” answers and for approval (Harasim et al., 1995; Mason, 1998). On the other hand, without the appropriate guidance of the instructor the discussion is likely to wither and die.

Most of the students were generally satisfied with instructor’s participation but, when pressed, several did indicate that greater instructor involvement might have helped stimulate the discussions. The instructor agreed that student participation may have increased if he had become more involved and tried to provoke more discussion.

Although the instructor contributed a large number messages to each discussion, they were usually clustered on one or two days. In other words, although he may have responded to the contributions of many students, he tended to do it all at once on the same day. This may have given the impression to students that the instructor was not really “present” other than on those one or two days when he posted messages. Research by Tagg and Dickinson (1995) indicates that this style of instructor participation does not encourage student participation. Their study concluded that student participation is enhanced if they feel the continuous presence of the instructor. They suggest this can be achieved through the use of messages of encouragement that are frequent and prompt, offer guidance, and address individuals rather than the group. The instructor’s participation met most of these criteria: his messages were positive and encouraging, they sometimes offered guidance, and they were mostly addressed to individuals. However, they were not frequent and prompt, and they were clustered rather than dispersed throughout the discussions.

The instructor also may also have been too eager in his desire to provide a student-centered environment as the online teaching literature suggests (Berge, 1995; Davie, 1988; Davie & Wells, 1991; Harasim et al., 1995; Paulsen, 1995). When it became evident that students were not participating as actively as he would have liked, it may have been necessary to intervene and provide support sooner and more frequently. As well, the instructor’s perception of these students’ involvement as adequate and of their general attitude as passive may have influenced him in not seeking further comments or posting requests for increased interaction.

Finally, it should be noted that the lack of stimulus for involvement and interaction may itself have been a factor in the general lack of participation. Several students and the instructor commented that there did not seem to be anything to “grab on to,” that there was a lack of dissonance or disagreement that could spark a sustained and interactive discussion. These results support the literature, which suggests that online education requires a new pedagogy for which conventional teaching in face-to-face environments does not adequately prepare instructors (Berge & Collins, 1995; Harasim et al., 1995; Paulsen, 1995).

Two course design issues that seem to have had a major impact on participation were the participation marks and the deadlines for participation. Several students commented or implied that they participated solely for the marks and that when they had made the minimum required contribution they stopped. Others commented that they would sometimes opt not to participate if they needed to spend time on an assignment for another course that was worth more marks. So, instead of stimulating participation, the marks seem to have been used strategically by some students to get maximum marks for minimum participation.

The deadlines for participation had a similar effect in that instead of encouraging students to participate early and often, the deadlines seem to have caused some students to wait until the last moment to contribute. By having the deadlines so close to the end of the discussion, little or no time was left for other students to respond and for a sustained discussion to develop.

Although this course may not have measured up to some of the descriptions of computer conferencing in the literature, most of the students and instructor felt that there was more participation and interaction in this class than in similar face-to-face classes. The main reason for this seems to relate to three of the key attributes of computer conferencing: time-independence, place-independence, and the many-to-many communication. The convenience of being able to participate at any time and from home were the first factors cited by most students as facilitating their participation. Even students who admitted to having trouble handling the self-directed nature of the course commented that they found these attributes facilitated participation. This may not be as paradoxical as it first sounds. Students who admitted to procrastinating because of the time-independence usually ended up making some contributions to the discussions. So although time-independence may have played a part in postponing their participation, in the end it allowed them to participate because the classroom never closed. Their contributions may have been perfunctory, but these attributes of computer conferencing allowed them to make them. Add to this the several students who said they felt less inhibited in the asynchronous computer conferencing environment than in face-to-face situations, and we have a possible explanation for why there may have been more participation in this online course than in similar face-to-face courses.

The institutional context in which the online course is offered appeared to have played an important role in the participation of the students in this course. That is, the fact that this course was the only distance education course in their program appears to have had a negative impact on their participation because of the conflict between the time-independent nature of this course and the time-dependent nature of their other courses. This factor is not mentioned in the literature and was not anticipated in the conceptual framework.

Methodological problems and differences in approach in the studies that have attempted to analyze the educational quality of computer conference transactions make comparisons with this study difficult. Henri (1989), for example, used a different conceptualization of critical thinking and found most students were using lower-level clarification skills at the surface level. Mason (1991) did not look specifically for evidence of critical thinking, but used a typology of six types of student contributions. She concluded that students were reflective, self-directed, and active. Harasim (1991, 1993a) found students used active questioning, elaboration, and/or debate. Webb, Newman, and Cochran (1994) and Newman, Webb, and Cochrane (1995) did find evidence of critical thinking, but in addition to using a different conceptualization of critical thinking they also ignored the quantity of participation in their analysis.

Several factors appear to have had an impact on the students’ ability to use critical thinking skills in their contributions to the discussions: cognitive maturity, the instructor’s style of teaching, the students’ experience with a dialogical style of teaching, and their understanding of critical thinking.

The work of King and Kitchener (1994) and Perry (1970) suggests that in general, age and educational level are reasonably accurate proxies for cognitive maturity and that students in their early to mid-20s have not generally reached the higher levels of cognitive maturity that allow them to engage in reflective thinking. King and Kitchener’s Reflective Judgment Model describes the development of epistemic cognition from childhood to adulthood. There are seven stages in this developmental progression in reasoning that represent “distinct sets of assumptions about knowledge and how knowledge is acquired” (p. 13). Research conducted using this model found that reflective judgment scores increased consistently with age and educational levels and that college freshmen and seniors tended to view knowledge as absolute or uncertain and idiosyncratic to the individual (King & Kitchener, 1994).

Support for this explanation is found in the analysis of the students’ understandings of the concept of critical thinking. Most did not have a complete understanding, and several had difficulty articulating what they thought it meant to think critically.

Teaching style is another issue that can have an impact on students’ ability to exercise their critical thinking abilities. Sternberg and Martin (1988) suggest the best approach for facilitating this is a dialogical style of teaching in which there is ongoing interaction between students and the instructor, and that involves discussion, inquiry, and the free exchange of ideas. This is also the essence of the recommendations of Harasim et al. (1995), Berge (1995), and Paulsen (1995) for online teaching. As discussed above, the instructor followed most of these recommendations and tried to use a dialogical teaching approach, but its effectiveness in facilitating critical thinking may have been diminished by the fact that participation and interaction were limited, and that when this became obvious, the instructor did not adjust his approach in order to stimulate greater participation and interaction. As discussed above, most of these students were accustomed to a didactic style of teaching and content-based courses. The dialogical style of teaching used in this course and its focus on process rather than content may have been incompatible with the experience of some of these students. The visible cues of student engagement available in the face-to-face classroom are not available in the online classroom, so in using a dialogical approach the instructor must also be prepared to become more interventionist and directive than is suggested in the literature in order to foster participation and critical thinking.

The results of this study indicate that getting computer conferencing to work in the way envisaged by some of its proponents is not a simple task. Although the technology may have attributes that have the potential to facilitate a dynamic and interactive educational experience, making this happen depends on much more than the technology. Of all the factors that help to explain the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of participation in this course, most have little to do with the technology of computer conferencing. Student characteristics such as their previous experience with distance education or independent study, their cognitive maturity, and their experience with participatory and interactive learning environments seem to be necessary preconditions for the successful implementation of computer conferencing where success is measured by high levels of participation, interaction, and critical thinking. The context in which the computer conferencing is implemented is also key. In campus-based environments, a single distance education course using computer conferencing in a student’s program may turn what are considered positive attributes into negatives. Time- and place-independence, instead of offering flexibility, may offer too much temptation to procrastinate. It seems that a course that allows a student to participate anytime, anywhere is easily forgotten when all the student’s other courses demand attention at particular times and places. Time-independence, by default, becomes time-dependence as the course with flexibility gets put off until everything else has been attended to. Student perceptions of the factors that facilitated their participation in this course support the view that the attributes of computer conferencing play an important role, but it is also clear from what the students had to say that meaningful participation and interaction depend on more than these attributes. Just as having a classroom with comfortable seats and a whiteboard does not necessarily ensure an effective course, having an online environment with the attributes of time- and place-independence, many-to-many communication, computer mediation, and text-based communication does not ensure an effective online course. The results of this study support the view of Harasim et al. (1995) and others that these attributes must be exploited by using appropriate design and facilitation techniques. The results also suggest that student situational and dispositional characteristics must also be taken into account. Effectiveness, then, depends on an appropriate combination of factors related to student characteristics, course design and facilitation, and the attributes of computer conferencing.

Future research could build on the results of this study by focusing on one or more of the factors identified. For example, it would be useful to know what impact different styles of instructor participation have on student participation.

Two other related factors that emerged from this study were the lack of student experience with distance education and students’ difficulty integrating this distance education course with the rest of their campus-based program. These factors could serve as the basis for a future study that compares the participation of full-time distance education students with those taking only one computer conferencing course as part of a campus-based program.

There also appears to be a need for research that compares online instruction with other modes of distance education for their effectiveness in promoting participation and critical thinking. This type of comparative study might help to isolate the impact and role of some of the key factors that were suggested by this study.

A future study might examine whether students’ understanding of critical thinking has an impact on their use of critical thinking skills and how these skills could be developed in an online environment.

The results suggest that students, like instructors, need adequate preparation before they can work online effectively. If an online course has many newcomers, this period of adjustment can be unproductive, and this suggests that strategies for preparing students for the online environment should be considered. For example, having a mandatory noncredit online course that introduces students to online learning and how to make effective use of the online environment might help ease the transition from the classroom.

If the course that is being offered using computer conferencing is the only distance education course that students are enrolled in, it is worth considering having several face-to-face sessions during the term. Many students in this course had difficulty integrating this distance education course into their campus-based program, and several indicated that face-to-face sessions might have helped. These could help ease the transition from a campus-based program to a distance education format, particularly for on-campus students who have had no previous distance education experience. They might also help students develop a social connection that facilitates their online participation. In this regard, a synchronous chat facility might be worth experimenting with, again to ease the transition, in this case from synchronous to asynchronous communication.

Online participation has to be seen by students as something integral to their success in the course. If it is viewed as busy work that they do only in order to get the participation marks, then it is unlikely that meaningful discussions will result. Some students in this course willingly gave up some of their participation marks because they knew they could get a satisfactory grade by completing their assignments and writing the examinations. Having students work collaboratively online to complete one or more assignments and then participate in an online discussion of these assignments, using the record of the discussions as a basis for an assignment, or having students each moderate their own discussion are suggestions for making online activity integral to the course.

Another practical issue is how participation deadlines are structured. The results of this study indicate that deadlines should be established near the midpoint of the discussion so that adequate time is allowed for follow-up comments. In addition, instructors should consider establishing two deadlines, one for the initial contribution and a second for a follow-up comment.

Whether or not one subscribes to the view that online instruction is a new paradigm, it is without question a new and different form of instruction for instructors who are used to teaching in a classroom, particularly if they are accustomed to practicing a didactic style. It is unreasonable to expect instructors to shift from the classroom to the online environment without adequate preparation. Without proper training in the principles and practices of online teaching and learning, instructors will probably attempt to transfer their classroom approach to the online environment.

The following is a list of the opening questions that were posed to students and the instructor during the semi-structured, open-ended interviews. After each question, or series of questions, is an explanation of the reason(s) for asking the question.

1. I am trying to get an idea of what things might have made it easier for you to participate in the computer conferences and what things might have prevented or inhibited you. First of all, can you think of anything that you felt encouraged you to participate or made it easier for you to participate?

2. Can you think of anything that prevented or inhibited you from participating? Depending on responses, subjects will prompted with more specific questions relating to different components in the conceptual framework as follows:

3(a) Was there anything about the way the computer conference activities were designed or organized that you felt helped or hindered your participation?

3(b) Was there anything about computer conferencing itself that you felt helped or hindered your participation? Depending on responses, prompt with examples such as the text-based nature, the ability to log in any time, information overload etc.

3(c) What about your own personal situation? Was there anything related to this that helped or hindered? I'm thinking of things like your study environment at home, your other responsibilities interfering with studies and so on.

All of the initial interview questions are based on the conceptual framework in which four main factors are identified: the attributes of the medium, the design of the learning activities, student situational factors and student dispositional factors. The first two questions are broad, opening questions that do not relate to any specific factor. They are intended to be conversation starters and to get the subject thinking about what may have hindered or facilitated his or her participation without influencing him or her with the preconceived factors of the conceptual framework.

Question 3 (a) (b) and (c) stem directly from the conceptual framework and relate to the design of the conference activities, the attributes of the medium and the student situational factors respectively. They will only be asked if the subjects do not raise these issues themselves in response to the broad opening questions (1, 2).

4. Finally I would like to get an idea of how you felt about this course before you took it and whether that changed. To start with, would you say you were looking forward to taking this course?

4(a) Did this attitude change over the duration of the course? Why?

4(b) What was your attitude towards computers in general before you took this course?

4(c) Did that change over the duration of the course? Why?

4(d) Now I would like you to think about your attitude towards the use of computer conferencing to take a course. What was that like before you took the course?

4(e) Did that change over the duration of the course? Why?

4(f) Do you feel that any of these attitudes you had at the outset had any effect on your participation? Why?

This series of questions relates to the dispositional factors in the conceptual framework. The purpose here is to probe the subject's attitudes towards computers and computer conferencing and to see if this changed over the duration of the course.

5. I am also trying to get some idea of what may have helped or hindered you in thinking critically about the questions that were posed in the seminars. First of all, I will explain what I mean by "critical thinking". Does that explanation make sense? Okay, now that you understand what I'm talking about, I would like you to think back over the course and try to remember if there was anything that helped you to use critical thinking.

6. Now, what about things that made it difficult for you to think critically. Can you think of anything? Depending on responses, subjects will be prompted with more specific questions relating to different components in the conceptual framework. See questions 3(a), (b), (c) and 4(f).

As with the first two questions, questions 5 and 6 are designed as broad conversation starters. In this case they deal with critical thinking rather than participation as in questions 1 and 2. Again, the purpose is to get the subject thinking about the issue without influencing him or her with the preconceived categories of the conceptual framework. Follow-up questions based on the four factors of the conceptual framework will be asked only if the subjects do not raise the factors in their responses to questions 5 and 6.

Bailin, S., Case, R., Coombs, J., & Daniels, L. (1993). A conception of critical thinking for curriculum, instruction and assessment. Paper commissioned by the Examinations Branch, BC Ministry of Education and Ministry Responsible for Multiculturalism and Human Rights in conjunction with the Curriculum Development Branch and the Research and Evaluation Branch. Victoria, BC: Ministry of Education.

Berge, Z.L. (1995). Facilitating computer conferencing: Recommendations from the field. Educational Technology, 5(1), 22-30.

Berge, Z.L., & Collins, M. (Eds.). (1995). Computer mediated communication and the online classroom. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Bullen, M. (1997). A case study of participation and critical thinking in a university-level course delivered by computer conferencing. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia.

Bullen, M., & Salinas, V. (1998, September). Postgraduate program in distance education and technology: Online instruction transcending national boundaries. Presentation to the Conference of the Consortium for North American Higher Education Collaboration, Vancouver.

Burge, E.J. (1988). Beyond andragogy: Some explorations for distance learning design. Journal of Distance Education, 3(1), 5-23.

Burge, E.J. (1994). Learning in computer conferenced contexts: The learner’s perspective. Journal of Distance Education, 9(1), 19-43.

Davie, L.E. (1988). Facilitating adult learning through computer-mediated distance education. Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 55-69.

Davie, L.E., & Wells, R. (1991). Empowering the learner through computer-mediated communication. American Journal of Distance Education, 5(1), 15-23.

DeGoede, M.P., & Hoksbergen, R.A. (1978). Part-time education at the tertiary level in the Netherlands. Higher Education, 7, 443-455.

Eastmond, D.V. (1994). Adult distance study through computer conferencing. Distance Education, 15, 128-152.

Ennis, R.H. (1987). A taxonomy of critical thinking dispositions and abilities. In J.B. Baron & R.J. Sternberg (Eds.), Teaching thinking skills: Theory and practice (pp. 9-26). New York: Freeman.

Feenberg, A. (1987). Computer conferencing and the humanities. Instructional Science, 16, 169-186.

Garrison, D.R. (1993). A cognitive constructivist view of distance education: An analysis of teaching-learning assumptions. Distance Education, 14, 199-211.

Hansen, E., et al. (1991). Computer conferencing for collaborative learning in large college classes. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 334 938)