VOL. 13, No. 2, 51-65

The lack of empirical testing of theories in past studies in distance education has resulted in a fragile theoretical basis of this field. Investigating 121 learners’ experiences with videoconferencing, this study used path analysis to examine the postulates of Moore’s Theory of Transactional Distance. A major focus of the study was estimating the effects of the dimensions of dialogue, structure, learner autonomy, and transactional distance—the constituent concepts of Moore’s theory—on learning outcomes in such a learning environment. In-class discussion, one of the dimensions of dialogue, was found to contribute positively, directly, and indirectly to learning outcomes, whereas transactional distance between instructors and learners was inversely related to learning outcomes. None of the dimensions of structure and learner autonomy was found to have significant effects on learning outcomes. The data suggested that when learning outcomes were assessed only in terms of the student’s perception of how much he or she has learned, the relationships among the concepts in the transactional distance theory were only partly supported.

Dans les études antérieures menées en éducation à distance, le peu de vérifications empiriques des théories nous a légué des fondements théoriques faibles. Cette étude, qui analyse les expériences d’apprentissage par vidéoconférence de cent vingt et un apprenants, a adopté une analyse causale des postulats de la théorie de Moore sur la distance transactionnelle. L’étude s’est attachée à évaluer les effets du dialogue, de la structure, de l’autonomie de l’apprenant et de la distance transactionnelle--concepts constituants de la théorie de Moore--sur les résultats d’apprentissage dans un tel environnement d’apprentissage. La discussion en classe, qui est l’un des aspects du dialogue, s’est révélée contribuer de manière positive, directement et indirectement, aux résultats d’apprentissage, alors que la distance transactionnelle entre formateurs et apprenants était en rapport inverse avec les résultats d’apprentissage. Il est apparu que ni la structure ni l’autonomie de l’apprenant n’entraînaient d’effets significatifs sur les résultats d’apprentissage. Les données laissent entendre que si l’on évalue les résultats d’apprentissage en s’appuyant seulement sur la perception du « combien » les étudiants ont appris, les corrélations entre les concepts de la théorie de la distance transactionnelle ne sont que partiellement corroborées.

The distance education context has evolved toward greater complexity, particularly in relation to the variety, power, and flexibility of delivery systems. The changing field needs theories that reflect these changes in order to provide guidelines for practice. However, most previous research has focused on either the descriptions of various programs or the evaluation of student achievements and cost-benefit analysis to demonstrate the effectiveness of distance education systems (Saba & Shearer, 1994). As a result, little consideration has been given to developing a theoretical basis for the field. Keegan (1993) has argued the need for fostering theory development to serve as a basis for systematic study, to contribute to conceptual insights about the complexities of distance education, and to develop methods for enhancing the teaching-learning environment. This article is an attempt to move in that direction by addressing the applicability of Moore’s Theory of Transactional Distance to the current videoconference learning environment.

One of the few scholars to develop a theory of distance education is Moore (1973). Identifying dialogue, structure, and learner autonomy as the key constituent elements of distance education, Moore (1993) proposed the concept of transactional distance, a distance of understandings and perceptions that may lead to a communication gap or a psychological distance between participants in the teaching-learning situation. He believed that transactional distance must be overcome by teachers, learners, and educational organizations if effective learning is to occur (Moore & Kearsley, 1996). Moore (1993) also argued that degree of transactional distance between learners and teachers and among learners is a function of the extent of the dialogue or interaction that occurs, the rigidity of the course structure, and the extent of the learner’s autonomy.

Moore (1990) has repeatedly called for “the generation of hypotheses and empirical testing” (p. 14) of his theory and for research to help establish the relationships among these four variables in various educational situations. However, to date there is a paucity of empirical research dealing with these issues.

We were able to locate only three published studies that explicitly investigated the linkages among the concepts involved in Transactional Distance Theory. Claiming to be the first effort to understand the relationships among dialogue, structure, and transactional distance, Bischoff (1993) sampled 221 student volunteers in 13 public health and nursing graduate courses at the University of Hawaii to investigate their perceptions of dialogue, structure, and transactional distance (Bischoff, Bisconer, Kooker, & Woods, 1996). Responses to questions about these three variables were collected from students in both traditional and distance-format courses delivered via Hawaii Interactive Television Service (HITS), a two-way audio, full-motion television system operated by Hawaii Public Television. The results of this study led to the conclusion that dialogue and structure scale scores predicted transactional distance. Dialogue was found to be inversely related to transactional distance, whereas structure was directly related to transactional distance. This study also found that dialogue scores were significantly higher for distance-format courses than those for traditional-format courses and that dialogue and structure scores were significantly higher in courses offering electronic mail support than those in courses without e-mail interaction.

Saba (1988) proposed a system dynamics model in the form of a causal or feedback loop representing the relationship among Moore’s variables of dialogue, structure, and transactional distance. Saba and Shearer (1994) empirically tested this model in desktop videoconferencing instruction to examine the relationships among these variables. They noted that transactional distance was a function of structure and dialogue—transactional distance decreased when dialogue increased and structure decreased, and that when structure increased transactional distance also increased, but dialogue decreased.

Bunker, Gayol, Nti, and Reidell (1996) measured the effect of changes in structure on dialogue in an international, multicultural distance education course taught via audioconferencing. The research setting was a course that brought together a virtual class of approximately 100 students at nine sites located in eight different cities in four countries. The authors found that different types of instructional structure had a role in determining learning participation, that is, in predicting dialogue.

These three studies supported the presence of correlations among dialogue, structure, and transactional distance and Moore’s assertion that transactional distance is a function of dialogue and structure. However, they failed to address several important issues related to Transactional Distance Theory. First, they did not include the third constituent concept of Moore’s theory (learner autonomy) and its effect on transactional distance. Second, both the Bunker et al. (1996) and the Saba and Shearer (1994) studies emphasized dialogue as synchronous, in-class interaction (either face-to-face or via teleconferencing) rather than considering in detail the effects of asynchronous communication (such as e-mail) as a means of interaction. Third, they did not explore how various characteristics of the teaching-learning situation affect dialogue, structure, learner autonomy, and transactional distance. Finally, they failed to explore how dialogue, structure, and transactional distance relate to student learning.

Other researchers, although not explicitly linking their analyses to Transactional Distance Theory, have reported relationships of other factors to dialogue and structure. Thus Cyrs and Smith (1990) reported that as the size of the group increased, individual interaction decreased. Moore and Kearsley (1996) found that class size was negatively related to the flexibility of course structure and that learners with previous experience using the media of communication and with higher knowledge levels of the subject matter may participate more interactively and independently in learning activities. Young (1996) noted that the presence of the instructor in person affected the extent of dialogue that occurred:

Class participation decreased at the remote site and the ability for students to spontaneously ask questions decreased significantly. Many students noted that it is much harder to concentrate when the professor is at the other site ... It is harder [for students] to get the instructor’s attention at the remote site ... It takes [students] more energy to stay involved. (pp. 2-3)

The learner’s accessibility to electronic communication hardware and software such as computers and e-mail as well as the learner’s skill in operating the delivery systems and using learning resources such as e-mail and the World Wide Web have been found to affect the level of interaction that takes place in distance learning situation (Baynton, 1992; Benner, 1984; Dreyfus & Dreyfus, 1980; Hillman, Willis, & Gunawardena, 1994; Williams, 1993). “Learners need to possess the necessary skills to operate the mechanisms of the delivery systems before they can successfully interact with the content, instructor, or other learners” (Hillman et al., 1994, p. 32). Bischoff (1993) suggested that the level of material to be taught in the course, whether introductory or advanced, could affect the rigidity of course structure. Saba and Shearer (1994) proposed that (a) course content such as factual information or process may decrease the flexibility of course structure and (b) learners with prior knowledge of the content may increase the extent of dialogue that occurs.

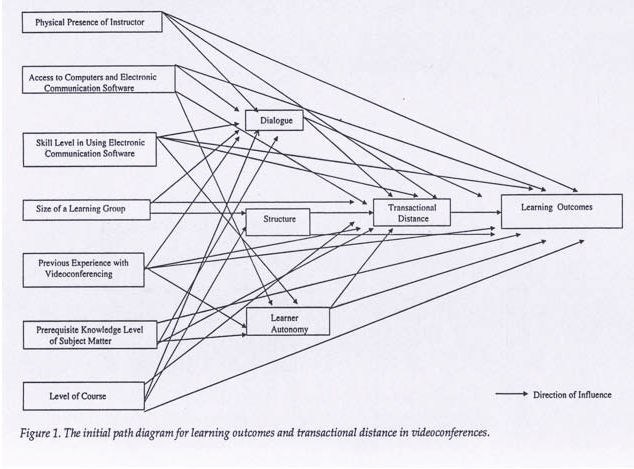

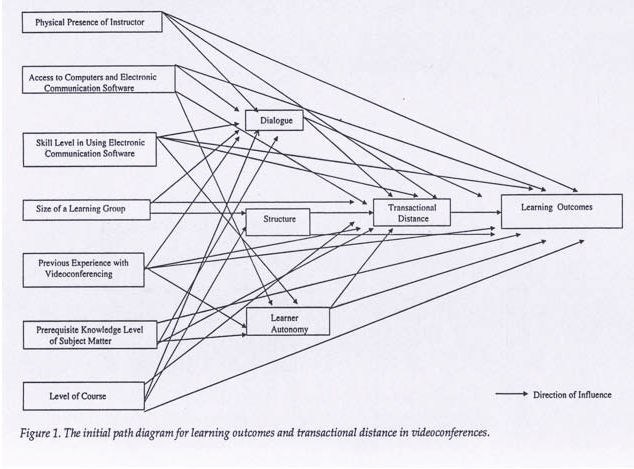

This study seeks to extend Moore’s Theory of Transactional Distance by incorporating these additional factors into a path-analytic framework along with indicators of dialogue, structure, and learner autonomy to enhance our understanding of transactional distance and learning. Specifically, the analysis addresses the following research question: What are the determinants of perceived learning outcomes and transactional distance when simultaneously examining (a) physical presence of instructor, (b) learner’s access to computers and electronic communication software, (c) learner’s skill level in using electronic communication software, (d) size of learning group, (e) learner’s previous experience with videoconference, (f) learner’s prerequisite knowledge level of subject matter, and (g) level of courses as exogenous (meaning “predetermined or starting”) variables, and using dialogue, structure, and learner autonomy as mediating variables (Figure 1)?

The sample. Data for this analysis were obtained from 121 participants enrolled in the 12 videoconferencing courses offered by the Pennsylvania State University in spring 1997. These courses originated from either the main campus at University Park or a branch campus at Harrisburg and were delivered to a variety of distant sites. Of the 12 courses, seven were at the graduate level; the other five were undergraduate. They covered a variety of subjects—including acoustics, adult education, aerospace, business logistics, counselor education, nursing, supervision, and Swahili. The enrollees included full-time or part-time students pursuing baccalaureate or advanced degrees and nondegree learners. The goal was to obtain a holistic picture of the learning experience in videoconferencing classes by targeting a diverse cross-section of learners. Students completed questionnaires during a class meeting period near the end of the semester.

Measurement of variables. Dialogue, structure, and learner autonomy were measured by asking a series of questions about various aspects of each of these concepts and factor analyzing the items developed for each concept to determine whether multiple ideas were involved. Extraction of factors was done using principal axis factoring, with an oblique rotation to allow the resulting factors to be interrelated. In each case the number of factors chosen was determined by calling into account: (a) the magnitude of the eigenvalue, with a minimum required value of 1.0; (b) the Scree Test; and (c) the interpretability of the item-grouping. Inclusion of a specific item in a given factor required a factor loading of at least .30 and at least a .10 difference between the item’s loading on this factor and the other defined factors (Chen & Willits, 1998).

Dialogue was measured by asking students enrolled in videoconference classes to indicate how frequently each of 13 different types of interactions occurred, including in-class student-teacher and student-student discussions among individuals at the same site and at different sites, out-of-class face-to-face interaction, and out-of-class electronic communication (e-mail, fax, voice mail, etc.). Answer categories ranged from 1 meaning Never to 7 meaning Always. Factor analysis of these 13 items defined three distinct aspects of dialogue-in-class discussion, out-of-class face-to-face interaction, and out-of-class electronic communication. A composite score for each of these dimensions was computed by taking the mean response score of the items within the factors. The higher the score, the more frequently students reported that type of interaction. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, measuring the internal reliability of the scales, were .84 for in-class discussion, .59 for out-of-class face-to-face interaction, and .58 for out-of-class electronic communication. Although modest, these coefficients were judged to be sufficient for the current analysis.

Questions concerning the structure of the course asked students to indicate on a scale of 1 (extremely flexible) to 7 (extremely rigid) the level of flexibility/rigidity of the: (a) teaching methods, (b) learning activities, (c) pace, (d) attendance, (e) objectives, (f) choice of readings, (g) requirements, (h) deadline of assignments, and (i) grading. The items were also factor analyzed, and two dimensions of structure were found. Flexibility/rigidity of teaching methods, learning activities, and pace comprised one factor that was termed course delivery/implementation. The remaining items formed a second factor labeled as course design/organization. Composite scores for these two factors were calculated; the higher the score, the more rigid students perceived the course to be in regard to delivery and design. Cronbach’s alpha was .69 for course delivery and .75 for course design.

Learner autonomy was measured by asking students to indicate the extent to which each of 11 statements described them. Answer categories ranged from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (completely true). Factor analysis of these items found two factors. These were termed independence (e.g., I am a self-directed learner; I am able to learn without lots of guidance; I am able to develop a personal study plan) and interdependenc e (e.g., I enjoy learning as a member of a team; I prefer learning in a group; I recognize my need for collaborative learning). Alpha was .82 for the factor termed independence and .77 for interdependence. Composite scores were calculated for both factors.

To measure transactional distance respondents were asked to rate the extent to which they perceived “a distance of understanding and perceptions” with their teachers, on-site classmates, and remote-site learners on a scales of 1 to 7, where 1 meant “extremely distant” and 7 meant “extremely close.” These three indicators were not sufficiently intercorrelated to form a single factor, so they were treated separately in the analysis.

The remaining variables were measured using the students’ responses to individual items on the survey form. Because some teachers traveled to various sites rather than always originating their instruction from the same location, each student was asked to indicate on a scale from 1 (never) to 7 (always) how frequently the teacher was physically present at his or her site. Seven-point rating scales were also used to obtain information on the students’ evaluations of their access to a computer and electronic software, their skill level in using e-mail and WWW resources, and their previous knowledge of the course subject matter. Previous experience with videoconferencing was indexed by the number of video courses the student had taken before this course (1 = None, 2 = One, 3 = Two or more). Course level was indicated as 1 = introductory, 2 = intermediate, and 3 = advanced. Size of the learning group was drawn from the teachers’ records and included the total number of on-site and remote-site learners.

Because the 12 videoconferencing courses covered a variety of subject areas, it was not possible to measure all students’ learning outcomes with a single objective assessment. Instead, learning outcomes, the ultimate dependent variable of this study, was measured by a questionnaire item asking the respondents to indicate how much they thought they had learned from the course using a scale of 1 to 7, where 1 meant Nothing; 7 meant A great deal.

Statistical procedures. Student responses to the items dealing with the study variables were analyzed using a series of multiple regressions in a path analysis approach. Causal modeling was used to specify the hypothesized determinants of transactional distance and perceived learning outcomes. The physical presence of the instructor, access to computers and communication software, students’ skill level in using electronic software, size of the learning group, students’ previous experience with videoconferencing, previous knowledge of the subject matter, and the level of the course were all expected to have an impact on the measures of dialogue, transactional distance, and learning outcomes. The indicators of course structure were hypothesized to be affected by the size of the learning groups and level of the course. Learner autonomy (independence and interdependence) were expected to be related to the learners’ access to computers and communication software, skill level in using electronic communication software, previous knowledge of the subject matter, and previous experience with videoconferencing. In addition, the dialogue, structure, and learner autonomy measures were expected to affect transactional distance and learning directly; transactional distance was also viewed as having a direct effect on learning.

Path analysis was used to test whether the data supported the proposed model by comparing observed relationships among the variables with those predicated (Asher, 1984). Using this method allowed for assessing not only the direct effects of variables (such as the effect of dialogue on transactional distance), but also the variable’s indirect effects through one or more other variables (such as the effect of dialogue on learning outcomes through transactional distance). The strengths of relationships (paths) were assessed using regression techniques. The path coefficients, obtained to represent the strengths of each of the direct effects, were tested for significance. Nonsignificant paths were deleted to arrive at a final model.

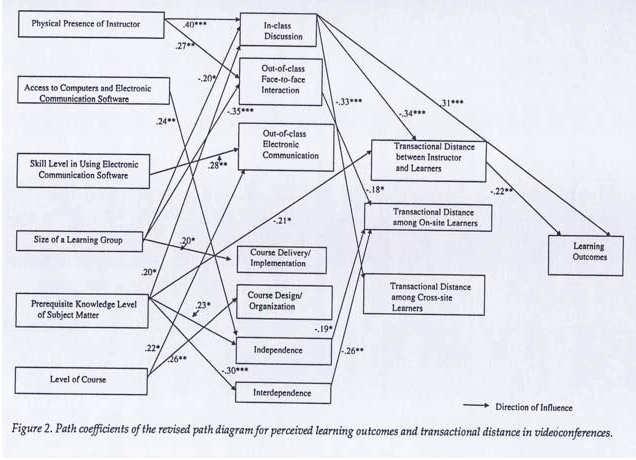

Path analysis of the study variables suggested the determinants of each dimension of dialogue, structure, and learner autonomy, transactional distance, and learning outcomes (Figure 2).

The findings of this study suggest that each of the concepts of dialogue, structure, and learner autonomy represent multifaceted ideas in a videoconferencing learning environment. Thus dialogue was found to consist of three dimensions: in-class discussion, out-of-class electronic communication, and out-of-class face-to-face interaction. Structure was differentiated into two dimensions (course design/organization and course delivery/ implementation.) Two separate dimensions of learner autonomy were delineated: independence and interdependence. Transactional distance was separately assessed in terms of the relationships between instructor and learner, among learners at the same site, and among learners located at different sites. Not only were these separate dimensions distinguishable in the current data, but their relationships with one another and with other variables considered here differed markedly. The multidimensional nature of dialogue, structure, and learner autonomy is important for understanding and extending Moore’s Theory of Transactional Distance and for suggesting new avenues of research, particularly for courses taught by videoconferencing. Awareness of these conceptual distinctions can also contribute to the effectiveness of practicing teachers by sensitizing them to the complexity of these elements in the teaching-learning environment.

When learning outcomes are assessed in terms of the student’s perception of how much he or she has learned, the factors affecting learning may not be as complex as one might believe. Only two factors (transactional distance between instructor and learners and frequency of in-class discussion) had direct effects on perceived learning outcomes. The greater the reported transactional distance between teacher and learners, the less the perceived learning outcomes; the greater the frequency of in-class discussion, the greater the perceived learning outcomes. The physical presence of the instructor and prior knowledge of subject matter increased in-class discussion and decreased teacher-learner transactional distance and thus indirectly contributed to perceived learning outcomes. As the size of the learning group increased, in-class discussion decreased and teacher-learner transactional distance increased with resulting negative indirect effects on perceived learning outcomes. However, none of the other factors considered here (including other indicators of dialogue, structure, learner autonomy, and transactional distance; learner’s access to computers and electronic communication software; learner’s skill level in using electronic communication software; learner’s previous experience with videoconferencing, and the level of the course) were found to have either direct or indirect effects on perceived learning outcomes. Distance education practitioners and researchers need to explore the question of whether the same conclusions would hold if other, more objective, measures (such as learners’ performances on exams and/or grades achieved) were used to index learning outcomes.

The suggestions of Moore’s Theory of Transactional Distance that dialogue, structure, and learner autonomy affect transactional distance were only partly supported. The linkages between dialogue and transactional distance differed depending on the type of dialogue and the indicator of transactional distance. As in-class discussion increased, the transactional distance between the instructor and learners decreased as did the transactional distance among cross-site learners. In-class discussion was not significantly related to the perceived transactional distance among on-site learners. Only out-of-class face-to-face interaction was directly linked with decreased perception of transactional distance among on-site learners. Out-of-class electronic communication was not significantly correlated with any of the transactional distance measures, perhaps because the frequency of use of this form of dialogue of out-of-class was minimal. Thus the various kinds of dialogue affected different types of perceived transactional distance rather than jointly contributing to a lessening of all types of transactional distance. Moreover, only the dialogue of in-class discussion was associated directly or indirectly with perceived learning outcomes. Neither of the two indicators of structure (course design/organization or course delivery/implementation) was linked to any type of transactional distance (as Moore suggested) or to learning outcomes. The measures of learner autonomy (both independence and interdependence) were both negatively related only to transactional distance among on-site learners; the other two types of perceived transactional distance (between instructor and learners and among cross-site learners) were not affected by either of the dimensions of learner autonomy.

Rather than dialogue, structure, and learner autonomy affecting transactional distance as Moore’s Theory hypothesizes, these data suggest that: transactional distance between instructor and learners (the only type of transactional distance linked with perceived learning outcomes) is not affected directly or indirectly by structure, learner autonomy, or two of the three dimensions of dialogue; it is related inversely to in-class discussion.

Why did neither structure nor learner autonomy relate to transactional distance between instructor and learners in this study? It could be that Moore’s Theory is correct and that this study has simply failed to uncover the relationships. It was the case that variations in the measures of structure and learner autonomy were limited. Whether this was a fault of the measuring instruments or resulted from a relative homogeneity of the sampled classes and students in regard to these variables is uncertain. Regardless, the low level of variation here would probably have served to attenuate these relationships.

On the other hand, it could be that the constituent concepts of Moore’s Theory do not actually affect transactional distance. That is, structure may not constrain emergence of “understandings and perceptions” or lead to “a communication gap” or “a psychological space of potential misunderstandings.” Indeed, it seems likely that structure of course design and delivery could sometimes facilitate understandings between teachers and learners. Similarly, rather than decreasing transactional distance, learner autonomy could actually interfere with interaction and thus contribute to a greater transactional distance between instructor and learners.

Given the importance of in-class discussion in decreasing transactional distance between instructor and learners and increasing learning outcomes, it is important to consider the circumstances that are correlated with student discussion in the classroom. Only three variables were associated with the incidence of in-class discussion (physical presence of instructor, size of a learning group, and prerequisite knowledge level of subject matter). Of these, the physical presence of the instructor was by far the most important. However, for distant sites, instructor presence may be impossible as a means of decreasing transactional distance with instructor and increasing learning outcomes. Additional research is needed to explore how substitute mechanisms might compensate for the lack of instructor’s physical presence at the receiving sites to decrease transactional distance between instructor and learner and increase learning outcomes.

Although out-of-class electronic communication is sometimes suggested as an alternative avenue of interaction in a videoconferencing learning environment, this study did not support the effectiveness of this practice. Future studies need to reassess the impact of electronic communication and to ascertain whether its usage can in some measure compensate for the absence of an instructor from the learning site.

Size of a learning group was also a predictor of in-class discussion with small size (i.e., fewer students) increasing discussion. In this study none of the 12 investigated classes was as large as 30 enrollees (the class sizes ranged from 4 to 28). Some guidelines for videoconference instruction have suggested that 20 to 30 student participants in a videoconferencing site represent an appropriate size (Cyrs & Smith, 1990; Willis, 1994; University of Maryland, 1996). This study suggests that fewer than this number of students is likely to enhance the intensity of in-class discussion.

Prerequisite knowledge level of subject matter was positively related to in-class discussion. For some courses that require certain prior knowledge of subject matter, instructors of these classes should provide the specific requirements to students to enhance the frequency of in-class discussion, decrease teacher-learner transactional distance, and increase learning outcomes.

Additional research on distance learning and on the efficacy of Moore’s Theory is needed both to evaluate the applicability of the revised path model to other learning situations and to extend the current analysis. Our study was based on a fairly small number of cases (N=121) and dealt with students at a single institution. Furthermore, it depended on students’ self-assessment of their learning. Replication of these procedures on other populations and using larger samples is called for. Moreover, further research should consider alternative measures, particularly for assessing learning outcomes. Although the present study’s use of the learners’ perceptions of how much they had learned is applicable across courses and presents a possibly important subjective perspective on learning, more objective measures should also be used.

The path models considered here were assumed to be recursive models and did not consider the possibility of statistical interactions. Other variables may need to be brought into the model to represent the teaching-learning situation in videoconferencing more accurately. Moreover, although recursive models represent the traditional and simplest form of path analysis, they deal only with unidirectional causal flow and do not allow for evaluation of the feedback loops and reciprocal causation that may occur. Last, consideration should be given to exploring whether these causal models differ for different types of students, different levels or types of classes, or by teacher characteristics.

Asher, H.B. (1984). Causal modeling. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Baynton, M. (1992). Dimensions of “control” in distance education. American Journal of

Distance Education, 6(2), 17-31.

Benner, P. (1984). From novice to expert: Excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley.

Bischoff, W.R. (1993). Transactional distance, interactive television, and electronic mail communication in graduate public health and nursing courses: Implications for professional education. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Hawaii.

Bischoff, W.R., Bisconer, S.W., Kooker, B.M., & Woods, L.C. (1996). Transactional distance and interactive television in the distance education of health professionals. American Journal of Distance Education, 10(3), 4-19.

Bunker, E., Gayol, Y., Nti, N., & Reidell, P. (1996). A study of transactional distance in an international audioconferencing course. Proceedings of seventh international conference of the Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education (pp. 40-44). Phoenix.

Chen, Y.J. & Willits, F.K. (1998). Dimensions of educational transactions in a videoconferencing learning environment. American Journal of Distance Education, 13(1), 1-21.

Cyrs, T.E., & Smith, F.A. (1990). Teleclass teaching: A resource guide. Las Cruces, NM: Center for Educational Development, College of Human and Community Resources, New Mexico State University.

Dreyfus, S.E., & Dreyfus, H.L. (1980). A five stage model of the mental activities involved in directed skill acquisition. Unpublished report supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFSC), USAF (Contract F49620-79-C-0063), University of California at Berkeley.

Hillman, D.C.A., Wills, D.J., & Gunawardena, C.N. (1994). Learner-interface interaction in distance education: An extension of contemporary models and strategies for practitioners. American Journal of Distance Education, 8(2), 30-42.

Keegan, D. (1993). Reintegration of the teaching acts. In D. Keegan (Ed.), Theoretical principles of distance education (pp. 113-134). London: Routledge.

Moore, M.G. (1973). Towards a theory of independent learning and teaching. Journal of Higher Education, 44, 661-679.

Moore, M.G. (1990). Recent contributions to the theory of distance education. Open Learning, 5(3), 10-15.

Moore, M.G. (1993). Theory of transactional distance. In D. Keegan (Ed.), Theoretical principles of distance education (pp. 22-38). New York: Routledge.

Moore, M.G., & Kearsley, G. (1996). Distance education: A system view. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Saba, F. (1988). Integrated telecommunication systems and instructional transaction. American Journal of Distance Education, 2(3), 17-24.

Saba, F., & Shearer, R.L. (1994). Verifying the key theoretical concepts in a dynamic model of distance education. American Journal of Distance Education, 8(1), 36-59.

University of Maryland. (1996). IVN faculty guide and technical training manual. MD: University of Maryland University College.

Williams, A.T. (1993). Efficacy of premium broadband videoconferencing in teaching cardiac arrest skill: A comparative study. Ann Arbor, MI: University Abstracts International.

Willis, B. (1994). Distance education: Strategies and tools. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

Young, W.H. (1996, November 1-3). Two-way interactive television delivery: Critical analysis and keys to success based upon student responses from their journals. Paper presented to the conference of the American Association of Adult and Continuing Education, Charlotte, North Carolina.

Yau-Jane Chen is an assistant professor in the Center for Teacher Education at the National Chung Cheng University in Ming-Hsiung, Chia-Yi 621, Taiwan. Fern K. Willits is a professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Sociology at the Pennsylvania State University, University Park.