VOL. 14, No. 1, 14-33

This article reports the results of an evaluation of a blend of educational delivery methods used over a two-year period in a one-year Primary Care Nurse Practitioner (PCNP) program in Ontario, Canada. The first of its kind in the province, this practice-based program was administered by a complex consortium of 10 universities that combined and shared resources to offer the program in English and French to students in all regions of the province using multiple delivery methods. Students, professors, and tutors responded to a questionnaire designed to assess their perceptions of and satisfaction with the delivery methods. Students also participated in focus group interviews. Participants were satisfied with all delivery methods and developed new technological skill sets that were perceived as transferable to other teaching, learning, and practice situations. They expressed greatest satisfaction with face-to-face delivery, an approach with which they were familiar. The most dramatic increase in comfort over time was with computer conferencing, although it was the least familiar technology at the beginning of the program. Ongoing technical support was emphasized as an important need. The findings will be of interest to those planning program delivery using multiple educational delivery methods.

Le présent article rend compte d’une évaluation portant sur l’utilisation, pendant deux années, de diverses méthodes de diffusion d’un programme annuel en soins infirmiers de première instance (PCNP). Ce programme axé sur la pratique, offert pour la première fois en Ontario (Canada), était sous la direction d’un regroupement complexe de dix universités. Celles-ci ont mis en commun et partagé leurs ressources afin d’offrir ce programme, en français et en anglais, à des étudiants répartis dans toute la province, en s’appuyant sur un large éventail de moyens de diffusion. Un questionnaire adressé aux étudiants, aux professeurs et aux moniteurs visait à évaluer leurs perceptions et leur satisfaction quant à ces divers moyens. Certains étudiants ont également participé à des groupes de discussion dirigée. Les étudiants se sont dits satisfaits de toutes les méthodes de diffusion et ont affirmé avoir acquis de nouvelles compétences technologiques, qu’ils estiment applicables à d’autres situations d’enseignement, d’apprentissage ou de pratique. Ils ont accordé leur préférence à l’enseignement face à face, qui leur était le plus familier. En début de programme, les étudiants étaient moins familiers avec le forum électronique et celui-ci leur déplaisait; toutefois, leur niveau d’aisance face à ce moyen a augmenté de manière significative en cours de route. Ils ont clairement souligné l’importance d’un soutien technologique continu. Les résultats de cette enquête intéresseront les concepteurs de programmes qui souhaitent utiliser des modalités et des technologies multiples de diffusion.

Primary Care Nurse Practitioners (PCNPs) are Registered Nurses (RNs) who focus on health promotion and disease prevention in a collaborative, multidisciplinary health care partnership. They have the authority to order certain diagnostic tests, diagnose, and treat common diseases. Primary Care Nurse Practitioner programs (PCNP) have been operating in the United States since 1965 (Ford, 1997; Thibodeau & Hawkins, 1994), but until recently, similar programs have not existed in Canada. Initial attempts to mount such programs in Ontario in the 1980s were unsuccessful. However, a decade later, changing heath care needs and political and economic pressures in the province prompted efforts to expand the scope of nursing practice. To meet these needs, RNs required advanced knowledge and skills in nursing and in areas traditionally associated with medicine such as diagnosis and treatment of specific common illnesses. The PCNP was viewed as the health care provider who could meet the requirements of this expanded role; consequently, a program to educate these practitioners was begun in 1995.

This 12-month program, the first of its kind in Ontario, is designed to prepare nurses to function in expanded primary care roles and is administered by a unique and complex consortium of 10 universities that are part of the Council of Ontario University Programs in Nursing (COUPN). Consortium members combine and share resources to offer the curriculum in English or French to full- and part-time students in all regions of the province. As well, the PCNP program uses multiple distance and traditional delivery methods to provide nursing education in rural and urban Ontario.

In 1996, having recognized the necessity to evaluate the quality and impact of the PCNP program, the Ministry of Health of Ontario (MOH) provided research funds to McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, for a comprehensive evaluation study. The purpose of the study was to evaluate the structure, process, and outcomes of the educational program; the placement and practice patterns of PCNPs in health care settings; and the impact of PCNPs on the quality of care, patient outcomes, and the health care system. In this article, evaluation of the educational delivery methods employed in the first two years of the PCNP program are reported.

Distributed learning through various technical and nontechnical methods has been used in nursing education programs for at least three decades. Billings and Bachmeier (1994), in their review of nursing literature from 1966 to 1992, identified 69 articles related to distance education and nursing. Of the 28 research-based articles, print-based (correspondence) modules, television, and audio-teleconferencing were the most common approaches adopted in the 1970s and 1980s. In the 1990s, print-based (correspondence), television, and audio-teleconferencing continued to be used, but the introduction of computer-mediated conferencing (CMC), and mixed methods that combined use of television, audio- and videotape, cable, and computer-managed instruction (CMI) had also become evident.

Three studies conducted in the 1990s that involved mixed methods for program/course delivery were identified by Billings and Bachmeier (1994): Cragg (1991), Luchsinger (as cited in Billings & Bachmeier, 1994), and McLelland and Daly (1991). These studies focused on RNs pursuing undergraduate baccalaureate education. For example, Cragg studied the influence of distance education on professional resocialization of 24 diploma-prepared RNs from four Canadian universities who took degree courses in nursing issues by audio-teleconferencing or print-based correspondence. Few differences were found in attitudes between students taking courses through either mode. The differences were more a function of professor personality and institutional attitudes toward students taking courses through distance education than of the actual delivery medium.

Similarly, Luchsinger (Billings & Bachmeier, 1994) researched the effect of distance education in associate degree nursing programs and found no differences in learning outcomes of students when several delivery methods were combined. Television, videotaped instruction, audiographic teleconferencing, audio-conferencing, and cable networking CMI were used. McClelland and Daly (1991) used audiotape, audio-conferencing, videotape, and correspondence in their study of 72 diploma-to-degree students enrolled in on-campus and satellite centers. They found on-campus students achieved higher grades than satellite students, who were older, worked longer hours, had more children, and drove further to attend classes. None of these studies described faculty attitudes, PCNP education, or the blend of distance education methods used in the PCNP program.

One of few studies that involved nurse practitioner (NP) participants was reported by Landis and Wainwright (1996). They examined how computer-conferencing was used to link on-campus NP students at the University of Texas at Galveston with a group of NP outreach students in one of three distance sites served by the graduate program. Both students and faculty found the medium facilitated communication. Outreach students gained comfort with the technology, felt connected to their colleagues, and were more satisfied with frequent faculty interaction than on-campus students. Plans were being made to expand its use to other remote sites.

In summary, although a variety of delivery methods have been successfully implemented in nursing programs, only one study focused on NP education by distance learning methods (Landis & Wainwright, 1996). They used a single technology—computer-conferencing—in the design of this program. No research literature was found regarding analysis of combinations of multiple delivery methods in a complex consortium structure such as that used in the Ontario PCNP program. Few addressed faculty attitudes. The current study is unique in its evaluation of multiple educational delivery methods in this context. As such, it should contribute to a better understanding of the effectiveness of these methods in a practice-based, complex, postbaccalaureate NP program.

The five courses that comprise the PCNP program are Pathophysiology for Nurse Practitioners, Advanced Health Assessment and Diagnosis (Assessment), Therapeutics in Primary Care (Therapeutics), Nurse Practitioner Roles and Responsibilities (Roles), and the Integrative Practicum (Practicum). Full-time study is over a 12-month period and part-time may take up to 36 months. Ten consortium providers offer courses in English, and two provide courses in French. To maximize program access, a combination of two or more of the following are used in each course: print-based modules (includes articles, learning guides, etc.) and textbooks, audio- and videotape, audio-teleconferencing (TC), video-teleconferencing (VC), Internet-based computer-conferencing (CC), and CD-ROM. Face-to-face (F2F) sessions are used for seminars and laboratory practice in the Assessment and Therapeutics courses and during the Practicum. On-site practice placements are also required in these courses. Not all professors, tutors, or students use every medium for each course whether from home, workplace, or university. The delivery methods are briefly described below.

Printed materials (course outlines, readings, assignments) and texts are available for all courses. In some courses (Assessment and Integrative Practicum), students are also provided with audio- and videotapes that contain specific content. Audio-teleconferencing is used in all courses for students to discuss course content and process with professors and each other. These conferences are recorded so those students who are unable to participate can listen to the discussion later.

Video-teleconferencing was used most often by French-speaking students. In one course (Assessment) offered in 1996, English-speaking students engaged in one VC, providing them with an opportunity to see and speak to each other. Internet-based computer-conferencing, asynchronous (delayed-time) communication through computer technology, gave students the chance to interact through written text at a personally convenient time and place. This strategy linked students and faculty over the entire province in a shared electronic learning space and was used in all courses for teaching or information sharing. The interactive, multimedia CD-ROM, developed specifically as a supplement for the Pathophysiology course, enabled students to work at their own pace, to visualize, interact with, and work through complex physiological concepts and processes that were translated into graphic displays or animations.

Evaluation of the distance education methods took place in 1996 and 1997. Participation in the study was voluntary. Data were collected from English and French professors, tutors, and 1996 and 1997 graduates. Most courses were taught by professors who were responsible for course development as well as implementation and evaluation. Tutors hired by each university were responsible for student course support in Assessment, Therapeutics, and Integrative Practicum courses. They facilitated tutorial and laboratory sessions.

In 1996, all graduates (N=30, from 135 admitted to the program), professors (n=10), and tutors (n=10) received a mail copy of an English or French researcher-designed, three-part questionnaire.1 Items were derived from the literature and experts in the field. Respondents selected the option that best represented their opinion of all items for each distance delivery method using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 reflected a negative opinion and 5 a positive one. Elements included: perceived satisfaction; changes in comfort with the technology; technological support; interaction and development of relationships with others; development of a learning community; and the ability to express opinions, reflect on, and integrate new learning. Students were also asked to rate their preference for and perceived effectiveness of the various media they had experienced in the program. In 1997, the questionnaire, which was modified slightly for the second cohort based on feedback from first-year participants, was mailed to 53 graduates (from 93 admitted in 1996), 10 professors, and 20 tutors.

Participants were assigned code numbers and not identified by name. Responses were returned by mail to the data collection center. No interaction occurred between participants and researchers during completion of the questionnaires. Those who did not return the questionnaire within one month received a telephone reminder and a second mailing, completion of which was requested within eight weeks. Quantitative responses were compiled and analyzed using descriptive statistics. A mean score of indicated that criteria were met. Mean scores of <<3 were examined as these suggested that the minimum criteria were not met. Appropriate PCNP curriculum changes could then be made. Open-ended questions were also included to encourage further comments. All data were subsequently shared in oral and written reports with program administrators (deans or directors and regional coordinators), professors, and tutors.

In addition to questionnaire data, in both years of the study, separate focus group interviews were held with volunteer program graduates drawn from different regions of the province. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and qualitative data summarized according to themes that emerged.

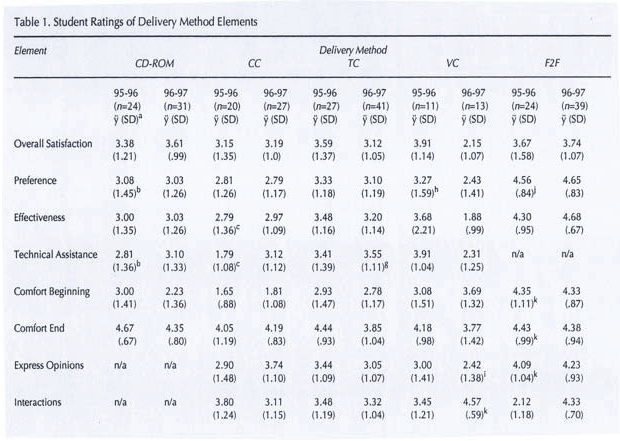

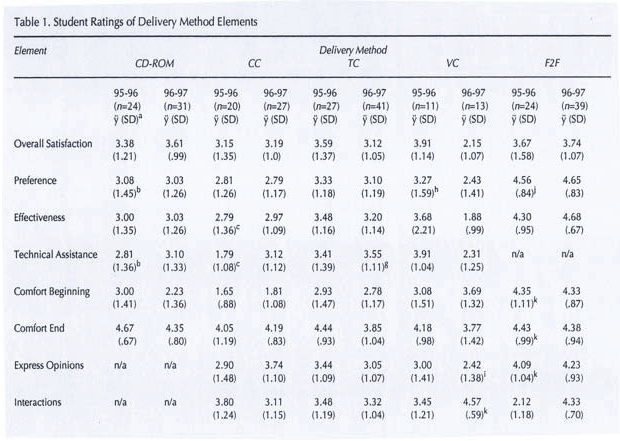

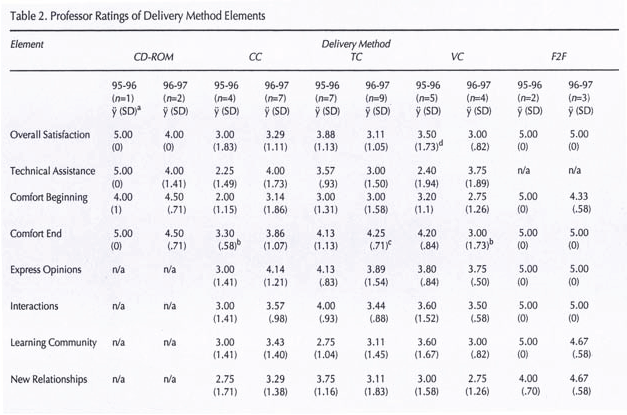

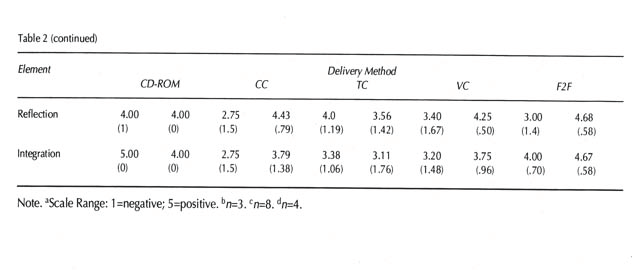

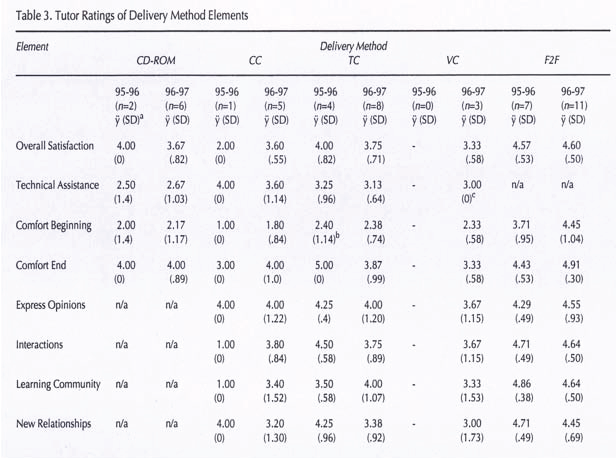

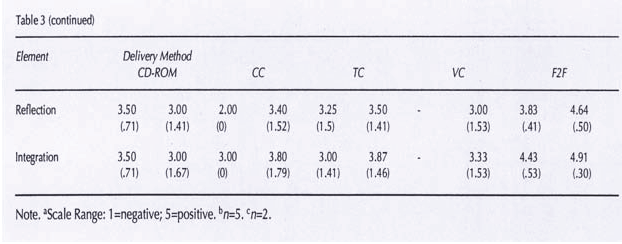

Data from three groups of participants are presented separately. Responses from participants in English and French programs are combined for each of the three groups as there were a limited number of French program graduates and few of those responded. Descriptive data are presented in Tables 1-3. Quantitative and qualitative data are included below. Participants were asked to rate only those technologies they had used while in the program.

Ninety percent of the 1996 graduating class (N=27), of whom two received instruction in French, returned completed questionnaires. They ranged in age from 26-53 years (M=35.7) and had an average of 12 years of work experience as nurses. Most (74%) had received their basic education in baccalaureate nursing programs, and 22% had some NP training prior to the PCNP program. The majority (70.4%) were married and employed full time (48%) or part time (42%). Approximately half (52%) participated in focus group interviews.

Seventy-nine percent (N=42) of the 1997 graduating class, of whom one was in the French program, returned completed questionnaires. These students were similar in age, experience, and marital and employment status to the 1996 class. They were 28-49 years of age (M=36.7), with an average of 14 years work experience as nurses. In contrast to the previous class, only 26% had received their basic education in baccalaureate nursing programs. The majority (81%) were married and employed (31% full time; 69% part time). Several (33%) were currently working as NPs. Fifteen (36%) stated they had NP training prior to entering the program. Forty-three percent (n=18) took part in focus group interviews. Graduates in both classes received little computer training in computer technologies prior to engaging in course content the first year, but workshops were made available at most sites the second year.

Quantitative and qualitative data from graduates in both years indicated that the multiple delivery methods were well received (see Table 1). Learning to use various technologies was a challenge, yet graduates from both years stated they were satisfied with the available options. Learning a new skill set, particularly computer technology, was welcomed despite initial apprehension. Frustration with the technology notwithstanding, satisfaction ratings for technical assistance increased or remained the same for all media except VC over the two years. One graduate noted, “It added a large amount of stress of being `pioneers’ but now that it’s `all said and done,’ I feel that the exposure increased my comfort and utilization of computers and communication technology.”

In both years, the F2F method was rated most positively in terms of overall satisfaction. Many students commented in writing and during focus groups that they preferred this method as it was the “richest and most satisfying.” Classroom instruction provided opportunities for them to establish relationships with each other. As one student stated, “There is no substitute for the real thing.”

The greatest increase in comfort with using media over the length of the program (in both years) was with CC. However, graduates disclosed frustration with the technology and a need for a sense of privacy and adequate technical support. These concerns were noted in written comments as well as in focus group interviews, for example “the more computerized tools used, the more `glitches’ with technology” and “need more support with technology.” Technical difficulties, particularly in the first year, and newness of the technology contributed to their frustration. Nevertheless, one graduate commented, “[CC] was the most important single factor that decreased the sense of isolation felt as a distance learning student.” In the first year, graduates perceived the freedom to express themselves openly in the CC medium as slightly less than desirable (M=2.90 (1.48)). As a result, a private online conference space was established for students in the second year. The mean rating then met the criterion (M=3.74 (1.10)). Graduates noted that despite improvements to the online network from one year to the next, ongoing technical support was crucial, especially for those who were not computer-literate. Orientation to all technologies before beginning the program, particularly those that were computer-based, was perceived as essential. “We need help with computers prior to classes starting”; “a period of orientation would be helpful.” This was particularly emphasized by the 1996 graduates. During the focus group interview, one graduate explained: “I just remember the guy going `OK, you do this, this, this’ and looking at this sea of blank faces and going `Oh, you need more basics than this?’“

Graduates of both classes generally agreed that each of the delivery modes could be used to facilitate useful student interactions and develop a learning community. Yet they responded that the development of professional relationships was less positive for VC (1996: M=2.73 (1.19); 1997: M=1.69 (1.03)). However, because this medium was seldom used by English-speaking students in 1995-1996 and not at all in 1996-1997, these results must be interpreted with caution as English-speaking students represent 96% of the respondents.

Similarly, TC did not meet the criterion (M=2.80 (1.14)) in the 1996-1997 evaluation. Graduates remarked that the large number of people participating simultaneously in TCs made it difficult to contribute individually during the time allotted. Teleconferencing was perceived as being more useful for “information giving” purposes. “Some were good if they were facilitated ... but that was the problem, they weren’t facilitated enough.”

Graduates also indicated that all media provided time and space for reflection and integration of learning, although F2F offered the greatest opportunity. Their ratings for the CD-ROM program for Pathophysiology did not meet the criterion for integration (M=2.84 (1.29) in the second year. They were positive about the program, and one remarked, “It was excellent in explaining visually `before your eyes’ pathophysiology that would be difficult to conceptualize from reading a text.” However, several graduates in both classes admitted they were unable to find time to complete this optional supplemental learning program due to the heavy courseload and other responsibilities. One student commented, “Downfall, too heavy in one program/course re Patho and multimedia; test, workload, conference, courseware etc. ... meant some means were sacrificed.” They felt there was insufficient time in their schedules to make use of optional learning resources. Focus group data confirmed these observations.

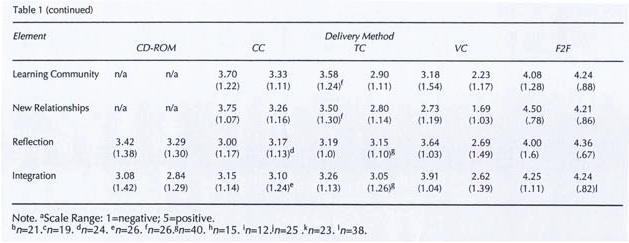

Eighty percent of the 10 professors, five of whom taught in French, returned questionnaires the first year. Their mean age was 39.8 years, and they had an average of 20 years of nursing experience. Of those who reported their highest level of education (N=6), two had baccalaureate degrees, two had masters degrees, and two had doctorates. Most (62.5%) had no prior training as NPs.

In the second year, most professors (90%), more than half of whom taught in French (n=5), whose mean age was 39.8 years, with an average of 26 years experience, returned the questionnaires. Of those who reported their highest level of education (n=8), two had bachelor’s degrees, three had master’s degrees, and three had doctorates. Of the latter three, one was not a nurse. Four professors reported prior training as NPs, but two had none. Those with training had obtained it either on the job or in a graduate program. Most professors were the same in both years of the study.

In the first year, the majority of the professors reported that they had little experience with the technologies used in the PCNP program. Nonetheless, all elements met the established criterion () for each delivery method except CMC, TC, and VC (see Table 2). Half of the elements (n=5) did not meet this criterion for CC, and one did not meet it for TC and VC. Professors found the conferencing system slow, and technical problems aggravated these difficulties. Technical issues were resolved in the second year, and all ratings on this element subsequently met the criterion (see Table 2).

In the second year, all elements met the criterion () for each delivery method except VC. Professors explained that they had developed more expertise with the various media as well as with the overall program: “The new `village’ was excellent, well run, and the people a pleasure to deal with.” They had also participated in planned orientations to the technology and received ongoing technical support. Like the graduates, professors in both years were most satisfied with the F2F medium.

Seventy percent of tutors (N=7) who returned questionnaires the first year, one of whom was tutoring in French, were on average 42.7 years of age. Their mean years of nursing work experience was 20. All had a university degree and most (85%) had master’s degrees. Fewer than half (43%) had prior NP training.

In the second year, 60% of tutors (n=12), of whom three were in the French program and whose average age was 42.2 years, returned questionnaires. All had a university degree. Three quarters of this group (N=9) had master’s degrees. One quarter (N=3) had prior NP experience.

As with the graduates and professors, all delivery methods were not used by every tutor. They rated only those they used in the program. In both years, tutors rated the F2F method most positively on almost every element (see Table 3), and because they had most contact with students in laboratory practice and tutorial sessions, this was not surprising. In the first year, comfort with each of the media increased from the beginning to the end of the program. Computer conferencing received a rating that did not meet the criterion for 5 of 10 elements; however, this finding should be viewed with caution as there was only one respondent. There was an evident change in 1996-1997 for this medium as all but one element met the criterion.

Overall, participants were satisfied with all delivery methods. Not only did student participants succeed in becoming NPs as an outcome of the program, graduates, professors, and tutors stated in their written comments that they had developed new technological skill sets that, in whole or in part, would be transferable to other teaching, learning, and practice situations.

The media, particularly CMC, TC, and VC, provided a lifeline for some students who would not otherwise have had access to the program or to each other. Many students lived in rural and remote regions of the province, so that completing an advanced certificate program in a traditional classroom setting would have been difficult. It might have necessitated relocation, additional expenses, and a sacrifice for those whose employers and families counted on their being close. In addition, CC, TC, and VC technology added a communication link that contributed to personal connectedness among the cohort of students and among faculty and students. These media were used to facilitate collaborative learning and contributed to interpretation, clarification, validation, and social construction of knowledge (Andrusyszyn & Davie, 1995). Creating ways for distance learners to interact with each other and with faculty, albeit through technology, is a fundamental element to successful distance program design and learning.

For others, however, the technology added a greater burden to their already complex personal and professional lives. These were adult learners (literature on this subject is abundant but not the focus of this research), who were probably grounded in more traditional approaches to teaching and learning. They may have preferred familiar methods. Dealing with computer connections to servers, which can on occasion be erratic, learning to navigate the Internet, and learning to communicate effectively through text using CC probably added to the rigors of an already intensive program. Not surprisingly, then, participants in both years expressed most satisfaction and comfort with F2F delivery, a traditional classroom method. It is also possible that they enjoyed learning the content addressed in F2F sessions more than other content areas. Familiarity and preferred content would reduce the stress of a learning environment with many unknowns, as a number of PCNP program aspects were new and under continuous development. Interestingly, both educators and learners in the first two years considered themselves pioneers in the NP arena.

As anticipated, comfort with each of the delivery strategies increased for all participants as courses progressed. Computer conferencing showed the most dramatic increase in the first year, despite its being the least familiar to faculty and students at the onset of the program. It was also the medium that required the greatest technical manipulation. Not only did participants have to acquire fundamental computer operations, they also had to learn more sophisticated activities such as how to access the Internet for program information and how to communicate with each other using a conferencing program. These procedures can be intimidating to technological novices.

Although comfort with CC increased from beginning to end of the second year, the shift was not as dramatic as in the first year. For faculty, greater familiarity with strengths and limitations of the technology may have accounted for their increase in comfort. Furthermore, factors that may have influenced both faculty and student perceptions and increased their sense of satisfaction might have been the following interventions: faculty development sessions during the second year; trial-and-error experiences of faculty and students in the first year; planned student orientations to technology in the second year; clearer expectations about and guidelines for computer access prior to students starting the program in the second year; more stable organization of the program in the second year; peer support; and ongoing technical support. It is also reasonable to assume that as faculty expertise with the technology increased, they would be able to provide more guidance and support to students. This would apply to CC as well as to other technologies such as CD-ROM, TC, and VC. Availability of ongoing technical support for each of the media is paramount, as this would reduce frustrations and allow users to attend to course content instead of expending needless energy on technical issues. Furthermore, assuring that processes are in place to orient faculty and students to required technologies before courses begin is an effective way of dissipating fears while increasing personal comfort.

Because each delivery medium has unique characteristics, not all will suit every learner or educator. As stated above, adult learners have different and preferred learning styles, multiple roles, and complex lives. Some may prefer experiential and/or experimental teaching-learning activities, whereas others need a more traditional visual or auditory method. Some may value interaction with others in small and/or large groups, whereas still others may prefer to learn on their own. Educators, on the other hand, may be skilled in the lecture-discussion method, whereas others may thrive on more facilitative approaches to knowledge development. Similarly, various delivery media have inherent features that may or may not appeal to all learners or educators. Audio-teleconferencing, for example, may appeal to those who rely on listening skills, whereas video-teleconferencing may suit those who use visual and auditory skills. Although these media are time- and place-dependent, they do provide greater connectedness to colleagues than CD-ROM, which normally requires individuals to work independently. CD-ROM, nonetheless, has the benefit of iterative learning and the merging of multiple media that stimulate interest. Therefore, although the issue of access bears thorough attention when planning programs so that no students are disenfranchised, the program delivery design also warrants consideration. Educators need to pay particular attention to the fit between content and method. Integrating a blend or a mixed-method approach to program delivery enables both students and educators to fulfill their differing learning and teaching needs and accommodate their teaching and learning styles.

Strengths and Limitations

The high response rate to the questionnaire and the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data were strengths of the study. The small population size and the geographic location of the program in one Canadian province are obvious limitations that may preclude generalizability of results. Participants from both years were graduates, professors, and tutors who were part of a leading-edge program with academic rigor. It is possible that responses from this group of selected individuals who were highly motivated adult learners and who probably already possessed the internal motivation to deal with the challenges of the program are biased in a positive direction.

In summary, multiple distance education delivery methods that combined traditional and nontraditional methods were used effectively in the PNCP program. They contributed to the delivery of a rigorous clinical program made accessible in a flexible and creative manner. The F2F method received the most positive ratings, while CC, TC, VC, and CD-ROM were viewed as facilitative to program completion. Participants who were novices in technologies learned considerably and acknowledged the benefits of accessibility, flexibility, and acquisition of a new skill set in their responses. However, their frustrations related to obtaining easy access to online technology must be addressed by educators planning distance programs. Every effort must be made to ensure that this access is quick and easy so that students can focus on substantive course content from the beginning and not have to spend inordinate amounts of time solving technological problems.

Designing a program offered through distance media requires careful planning. The design should address the nature of the learner, the educator, and the content, as well as the fit between content and delivery methods. Distance programs should be developed and offered with appropriate built-in supports and attention to individual student needs, so as to promote a healthy learning environment. Faculty interests and their expertise with various distance methods should also be considered. Guidance and support are equally important for those who teach.

The PCNP program, as described above, was the first program of its kind in Ontario. The complexity of the consortium as an organizational structure, coupled with multiple distance and traditional delivery methods, were unique program characteristics. Organizational leaders and faculty put much effort and energy into maximizing opportunities for success and carefully attended to the challenges that arose day to day and year to year. The motivation to initiate and conduct a successful program was strong, and the political, social, and economic stakes were high. In addition, students had a vested interest in seeing themselves and the program succeed. However, continued evaluation of the program over time is necessary to identify improvements and responses to changes. It will be interesting to compare NP practice patterns and perceptions of employers of those who studied by distance with those who completed traditional programs. This research is currently in progress. As well, ongoing evaluation of distance delivery methods should be pursued to assure their relevance. Additional investigations of attitudes of faculty and students involved in distance education should be undertaken. Further research should focus on the fit between the nature of the content and the delivery methods.

External critics may be skeptical about whether an advanced clinical program offered by distance can be as rigorous as one offered through traditional methods. Continuing evaluation of program content and use of multiple delivery methods with future classes are, therefore, necessary to demonstrate that standards of excellence are maintained and NP graduates are prepared to meet health care challenges of the new millennium.

Funding for this study was provided by the University of Western Ontario Vice President Academic Research Fund and the Ontario Ministry of Health.

The researchers acknowledge all participants and the research assistants Peggy Austin, Lisa Buckingham, and Lauren Griffith for their contributions.

Andrusyszyn, M.A., & Davie, L. (1995). Reflection as a design tool in computer-mediated education. Proceedings of the Distance Education Conference: Bridging research and practice. San Antonio, TX: Texas A & M University.

Billings, D.M., & Bachmeier, B. (1994). Teaching and learning at a distance: A review of the nursing literature. Pub. No. 19-2544. New York: National League for Nursing.

Cragg, E. (1991). Professional resocialization of post-RN baccalaureate students by distance education. Journal of Distance Education, 30(6), 256-260.

Ford, L.C. (1997). A deviant comes of age. Heart and Lung, 26, 87-91.

Landis, B.J., & Wainwright, M. (1996). Computer conferencing: Communication for distance learners. Nurse Educator, 21(2), 9-14.

McClelland, E., & Daly, J. (1991). A comparison of demographic characteristics and performance. Journal of Nursing Education, 30(6), 261-266.

Thibodeau, J.A., & Hawkins, J.W. (1994). Nurse practitioners: Factors affecting role performance. Nurse Practitioner 14(12), 47-52.

1. A copy of the questionnaire can be obtained by e-mailing Mary-Anne Andrusyszyn at maandrus@julian.uwo.ca.

Mary Anne Andrusyszyn is an assistant professor in the School of Nursing in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Western Ontario, London, Canada. She has been using distance technologies, particularly computer-conferencing, in her teaching and learning since 1991. Her e-mail address is maandrus@julian.uwo.ca.

Mary van Soeren is an acute care nurse practitioner in critical care in Ontario and an adjunct professor in the School of Nursing at the University of Western Ontario, London, Canada. Her interests are in teaching and implementing the nurse practioner role; her research involves muscle metabolism and exercise physiology. Her e-mail address is mvansoer@julian.uwo.ca.

Heather Spence Laschinger is a professor in the Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Nursing, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada. Her e-mail address is hkl@julian.uwo.ca.

Dolly Goldenberg, at the time of writing, was an associate professor in the Faculty of Health Sciences, School of Nursing at the University of Western Ontario, London, Canada. She is currently an adjuct professor there. She was introduced to computer-conferencing when co-teaching a course with Mary-Anne Andrusyszyn and has used this technology in courses for several years. Her e-mail address is dgold@shaw.wave.ca.

Alba DiCenso is a professor in the School of Nursing and in the Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at McMaster University. She is a career scientist of the Ontario Ministry of Health and co-editor of the journal Evidence-Based Nursing. She is the principal investigator of the study to evaluate the Primary Care Nurse Practitioner Initiative in Ontario. Her e-mail address is dicensoa@fhs.csu.mcmaster.ca.

ISSN: 0830-0445