VOL. 14, No. 1, 1-13

In a study with students in a distance-delivered nurse practitioner program, researchers examined student preferences for delivery methods. As well as examining learning style preferences and content, we asked students to report their experiences, state their preferences, and indicate problems they had encountered with distance technologies. From possible technologies the students selected print-based materials significantly more often than any other delivery method. CD-ROM and video-teleconferencing were the next most highly rated methods, followed by videotape, computer conferencing, audio-teleconferencing, and audiotaped lectures. Technological breakdown, poor technical quality of materials, and lack of familiarity with computers were among the factors that led students to give lower ratings to the more highly technological methods. Implications of the findings for distance educators are discussed.

Cette enquête porte sur un programme d’apprentissage à distance en soins infirmiers de première instance. La recherche s’est penchée sur les préférences des étudiants quant aux méthodes de diffusion de l’enseignement et quant aux modes d’apprentissage pour chaque contenu. On a questionné les étudiants sur leur expérience en tant qu’usagers des méthodes de diffusion, sur leurs préférences et sur les difficultés qu’ils ont éprouvées en utilisant les diverses technologies. Les étudiants ont exprimé une nette préférence pour l’imprimé, suivi du CD-ROM et de la vidéoconférence; venaient ensuite les bandes vidéo, les forums électroniques, les audioconférences et les cours reproduits sur des cassettes audio. Les problèmes technologiques, la faible qualité technique du matériel, ainsi qu’un manque de familiarité avec l’ordinateur expliquent leur insatisfaction envers les méthodes de diffusion utilisant les technologies complexes. L’article définit, à l’intention des éducateurs à distance, les enjeux soulevés par les résultats de cette enquête.

Distance educators can choose among an increasing array of delivery methods when seeking the best ways to provide effective, efficient learning opportunities. From traditional print-based modules, through interactive methods like audio- and video-teleconferencing, to the latest range of web-based capabilities, the options can seem overwhelming. Limitations on choices include the decisions institutions have made about investment in and support for particular technologies, the familiarity of course developers with different methods, the skill of teachers in exploiting the potential of each method, and learner preferences. The kinds of experiences that learners have had with different technologies and the impact of those experiences on their ability to learn can be expected to influence their perceptions of particular delivery methods. In this article, the impact of learners’ experiences with technologies on their preferences for distance delivery methods is examined. The findings come from studies of nurses taking a Primary Health Care Nurse Practitioner Program (PHCNPP) by distance education.

In a NODE-funded study that included both quantitative and qualitative methods, anglophone PHCNPP students’ preferences for distance delivery methods were examined. The study elicited student preferences based on type of content, learning style, and experiences with distance delivery technology before and during the program. It became clear that technology—both the practical problems encountered and affective responses to it—played a major role in determining which distance delivery methods students chose. These reactions are the focus of this article.

The PHCNPP is an initiative of the Ontario Ministry of Health that is offered by a consortium of the 10 universities in the province that provide nursing education. It is offered in English and French, with anglophone students enrolled at all 10 universities and francophones at the two bilingual universities. In each language, the five courses that make up the program are taught via distance from one of the 10 universities. Local tutors and preceptors provide face-to-face tutorials and clinical supervision. Professors have access to the distance education resources of the various universities. The program has a budget devoted to distance development and delivery. Therefore, being part of a consortium provides professors with more technology options than they would normally have at one institution. All students in the PHCNPP have experience with printed materials, audio-teleconferencing, audiotapes as backup for missed sessions, videotapes, web-based materials, computer conferencing, chat groups, and hot-links. In addition, a CD-ROM was used as a program supplement in one course for anglophone students, and video-teleconferencing was used regularly by francophones.

Although there is extensive literature on distance education, little work has been done in comparing multiple delivery methods and student preferences. Most studies of student reactions involve one or two technologies (Andrusyszyn, Iwasiw, & Goldenberg, 1998; Biner, Welsh, Barone, Summers, & Dean, 1997; Cragg, 1991; Schutte, 1996). Because all the students in this Nurse Practitioner program are exposed to a wide range of delivery methods, they present a unique opportunity for getting feedback from people with common experiences with a variety of distance methods.

Among the anglophone students, a descriptive correlational design was used to examine the relationships among learning preference, learning style, distance delivery method, learning outcome, and experience with technology. The research team developed a 12-page questionnaire. The first section included demographic data such as age, gender, program status, education before entering the program, time since completing latest education, and additional responsibilities like work, family, and community involvement.

In the second section, students were asked what conditions they preferred when learning new things. They then identified preferences for delivery methods when learning specific content in the program. Twenty-eight content areas, for example, goal setting with client as partner, diagnostic reasoning, ordering lab tests, and health policy, were identified by an expert panel as being uniquely covered and important in the program. For each of these content areas, students rated their preferences for seven distance delivery methods: video-teleconference, audio-teleconference, computer conference, print-based materials, audiotape, CD-ROM, and videotape. Students gave each delivery method a score ranging from 1 (highly undesirable) to 5 (highly desirable). Video-teleconference was the only choice that had not been used in the anglophone program. Students were asked to rate only those content areas they had actually covered in the program.

Four sections of the questionnaire dealt specifically with students’ experience with distance education technology. They were first asked about their level of familiarity with each of nine distance methods before starting the NP program. (Televised courses and Internet learning materials were added to the seven listed above.) Students then rated technical difficulties they had experienced in the program with the various distance methods they had actually used. They were also asked whether they had adapted any delivery methods to suit their personal learning needs (e.g., printing computer discussions or taping teleconferences). Finally, students rated their overall satisfaction with the different distance education delivery methods used in the NP program on a 5-point Likert scale, with an additional choice of “never used it.”

The population for the quantitative study was the 125 students who had been enrolled in one or all of the five courses of the anglophone PHCNPP program from September 1996 to August 1997. Of these, four had participated in the focus group held during the development of the questionnaire and were excluded from the mailing. A pretest questionnaire was mailed to 25 students. Because there were only minor changes from the pretest to the final questionnaire, the 19 pretests that were returned were included in the final sample. A total return of 86 questionnaires meant a response rate of 71%.

The students were asked to contribute written comments throughout the questionnaire, and most took the opportunity to elaborate on the topics addressed. Their comments were collated and reported with the quantitative results, adding depth to the responses. In addition, following the quantitative data analysis, six randomly selected respondents were interviewed using a semistructured interview schedule. These respondents provided additional information and commented on some of the questionnaire findings. The data were used to inform the quantitative findings. Comparisons were also made with the responses in a parallel qualitative study conducted with francophone students and professors.

All the interviewees and 96.3% of the 86 respondents to the survey questionnaire were women. Most reported they had multiple roles. Whether they were full- or part-time students, most of the survey respondents worked (89%) and had responsibility for care of children and/or elderly relatives (57%) and other community responsibilities (29%) like volunteer work. Fifteen percent had all three types of responsibility. Time was at a premium for them, and many expressed appreciation for being able to take the program through distance education because it would not have been possible for them otherwise. A quarter of them lived 100 or more kilometers from their home university; 11% more than 200 kilometers away.

Of the 86 students who responded, 41.5% had completed the program. More than 95% had experience with three of the five courses and 73% had completed or were taking the fourth theory course that precedes the final practicum.

Distance Education Experience Among Survey Respondents

The students were asked to indicate what their experience with distance education had been before starting the PHCNPP. The largest number of students had experience with print-based learning packages (63% reported they had used them often, whereas 12% said they had never used them) and videotaped materials (53%). Some had used audiotapes often (31%), and some had experienced audio-teleconferenced courses (22%). The respondents were least familiar with the high technology distance methods: 81% had never used computer conferencing, 79% had never experienced video-teleconferencing, 70% had no experience with Internet learning materials, and 67% had never used CD-ROM multimedia instruction before starting the PHCNPP.

Based on the courses they reported they had taken, all respondents had experience in the PHCNPP with print-based materials, audio-teleconferencing, and computer mediated conferencing; 98% of them had completed the course in which a CD-ROM was used. Forty-one percent had experience with videotaped materials used in the last course in the program. Audiotapes of audio-teleconferences were available for those who missed sessions in any of the courses, but only 52% had used them.

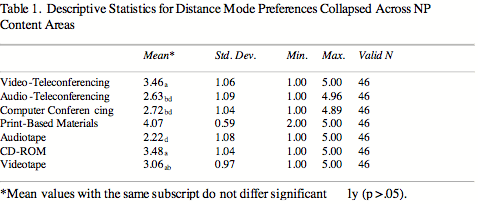

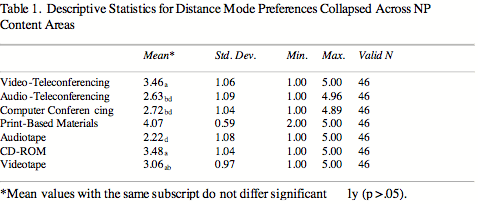

When asked about their preferences for learning specific content in the PHCNPP, students showed some variability in their preferences for delivery methods that reflected differences for factual material, psychomotor and interactive skills, and attitudes. However, there were patterns of responses that showed strong preferences for particular delivery methods no matter what the content. By collapsing scores across the 28 content areas listed, mean values were calculated for each delivery method and preference scores for each were created (see Table 1). A repeated measures ANOVA revealed an overall difference between the mean preferences. Post hoc comparisons (Bonferroni adjusted for multiple comparisons) between all pairs of mean method ratings were conducted. Print-based materials had the highest mean rating (M=4.07 on a 5-point scale. This rating was significantly higher than the mean ratings for all other methods. CD-ROM and video-teleconferencing were the next most highly rated methods (M=3.48 and M=3.46 respectively), followed by video-tape (M=3.06), computer conferencing (M=2.72), audio-teleconferencing (M=2.63), and audiotaped lectures (M=2.20). The low score for audio-tape did not differ significantly from the ratings for computer and audio-teleconferencing. It is worth noting that although video-conferencing was offered as a choice in this section of the questionnaire, these students had not experienced it in the program.

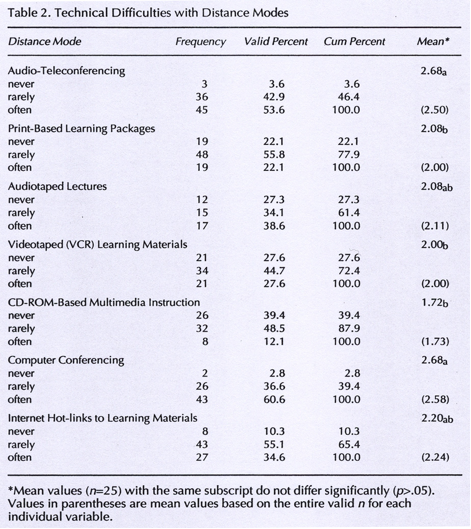

Survey participants were asked to indicate whether they had experienced any technical difficulties with the distance methods used in the Nurse Practitioner program (see Table 2). Valid sample sizes varied enormously, as many students had not used some of the methods available in the program, for example, audio- or videotapes. Repeated measures ANOVA requires equal cell sizes and thus employs listwise deletion of cases having missing data. This procedure reduced the sample size to 25 cases per variable for overall and pairwise comparisons of mean values.

The distance methods that presented the most trouble for respondents were computer conferencing (M=2.68 on a 3-point scale) and audio-teleconferencing (M=2.68), where the majority of participants indicated that they had experienced technical difficulties often (61% and 54% respectively). These findings were supported by the narrative comments on the questionnaires. Many participants expressed frustration because the server for computer conferencing had been down for periods of time, making it hard for them to participate. Several mentioned that they were not proficient with computer technology, that it took some time to get used to conferencing online, and that it was important to emphasize the dependence of the program on computer technology to potential applicants.

Students also noted that audio-teleconferences were of poor quality because the large numbers of participants made interaction difficult. Accessing audio-teleconferences and starting on time were other problems noted. Audiotapes of the teleconferences, made available to those who were unable to attend, were rated poorly because of sound quality. Videotapes that were used in some classes were also noted to be technically poor. Several participants expressed satisfaction with the CD-ROM developed for one of the courses, as well as the Internet hot-links that were part of several of the courses. Comments about print-based materials reflected concern about the volume of reading expected and lack of guidance about relative importance of articles, and some frustration with the quality of the reproduction, with missing pages in some cases.

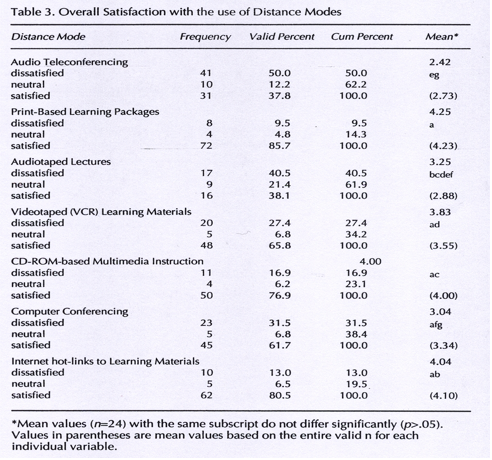

Survey participants were also asked to indicate overall satisfaction with the way the program was delivered using various distance methods (see Table 3). Responses were made on a 5-point scale ranging from very dissatisfied to very satisfied. As with the previous questions on technical difficulties, the valid sample size varied on these questions, with about 48% of respondents indicating they had never used the audiotaped lectures that served as backup for missed teleconferences. Use of repeated measures ANOVA further reduced the overall and pairwise comparisons by a listwise procedure to 24 cases. As a result, the means are reported based on a sample of 24 for comparison purposes along with means based on the total valid sample size for each variable. Although the 5-point scale was used to calculate mean satisfaction values for each variable, responses to this section of the questionnaire were recoded for easier interpretation by combining the very dissatisfied and dissatisfied, and satisfied and very satisfied options.

Considering only the satisfaction frequencies, the highest overall respondent satisfaction was with print-based learning packages (86%), followed by Internet hot-links (81%), CD-ROM based multimedia (77%), videotaped materials (66%), computer conferencing (62%), audiotaped lectures (38%), and audio-teleconferencing (38%). An overall significant difference was found between these means using repeated measures ANOVA (F 6,18=10.618, p=<<.001) along with pairwise comparisons supporting this general ranking on a continuum of satisfaction.

Pearson’s correlations were computed between the overall satisfaction variable and the items addressing the frequency of technical difficulties with the distance methods. In each case, a large and statistically significant negative relationship emerged for paired variables: audio-teleconference (r=–0.50, p=<<.001), print based (r=–0.52, p=<<.00l), audiotaped (r=–0.70, p=<<.001), videotape (r=–0.58, p=<<.001), CD-ROM (r=–0.49, p=<<.001), computer conference (r=–0.58, p=<<.001), Internet hot-links (r=–0.54, p=<<.001). Pearson’s correlations were also computed between the overall satisfaction variables and the corresponding mean preferences for distance methods for learning content in the program. Positive relationships were found for all paired variables at the p=<<.05 level.

The survey included a question on whether materials presented were individually adapted or converted to suit personal learning needs. Seventy-six percent indicated having made such a conversion. Of the 65 people who had made adaptations or conversions, 55 (84.6%) printed materials from a computer conference, 12 (18.5%) audiotaped lectures or tutorials, 16 (24.6%) audiotaped a teleconference, and 12 (18.5%) indicated that they made some other form of adaptation or conversion. For example, two students indicated in their narrative comments that they printed materials they accessed through Internet hot-links. These percentages do not total 100% due to the large number of multiple responses. Twenty-six respondents (40%) indicated making more than one type of adaptation or conversion.

Six women were interviewed for the qualitative portion of the anglophone study. All were part-time students with ages ranging from 31-54 years. All worked full time; five had family responsibilities and other personal challenges. Many of the responses, whether to questions specifically aimed at getting reactions to technology or discussing other aspects of the program, reflected the importance that technology played in their perception of the program. Several mentioned that without the opportunity to study by distance education, they would have been unable to take the program. They also emphasized the need for flexibility in the use of distance methods to deliver course content. They preferred methods that were time-saving and allowed personal choice of study time. On the other hand, they valued interaction and particularly commented on liking face-to-face meetings, both for learning specific skills and for meeting fellow students. To increase interaction, some had also arranged face-to-face meetings outside those organized for the courses. In commenting on distance methods, they reported that the printed course materials, computer conferencing and the Internet, CD-ROM, and contact with colleagues through so many different networks were helpful.

Discussing the preference expressed for print-based materials by survey participants, the interviewees stated that they considered these an essential foundation for learning. Print-based materials are flexible, portable, and familiar. Although respondents perceived them as being well laid out, with clear objectives, the volume of reading and lack of clarity about their relative importance caused frustration.

Participants also commented on their satisfaction with other delivery media. Videotaped content was satisfactory, but the production quality was poor. Audio-teleconferences caused problems because of difficulties with scheduling, making contact, participating actively in large conferences with many sites, lack of structure, and lack of expert presenters. The CD-ROM was seen as useful. It was also reliable and allowed student choice in timing and interaction. The use of computers received mixed reviews. Computers were recognized as useful to stay on track, but they were also a source of frustration and anxiety because of lack of previous experience. Lack of computer support at home was a major problem. Despite their frustrations with learning the new technology, most persevered and were subsequently pleased at having learned new transferable skills that they anticipated continuing to use in their careers.

As mentioned above, a parallel francophone study involved interviewing seven students who had completed the program. In the area of technology, the francophone respondents had similar reactions to the delivery methods, except for their experience with audio- and video-teleconferencing. Because the numbers of students in audio-teleconferences were smaller, there were few complaints about inability to participate actively in discussions. Video-teleconferencing was preferred to computer conferencing, but frustration was expressed about the frequency of technological breakdowns with the equipment.

These studies were carried out with only one program and fairly homogeneous groups that were predominantly female. Students were highly motivated adult women with multiple responsibilities and limited technological and distance education experience. Whether the results can be generalized to other groups is questionable, but the students’ responses do provide some insights for distance educators.

Student preferences for distance delivery methods are influenced by many factors. Although this article concentrates on the students’ responses to technology, examination of the results from the entire questionnaire and interviews indicates that a combination of life circumstances, approaches to learning, specific types of content, and experiences with technology all played a part in determining preferences. The fact that the PHCNPP was preparing students for a new role and required students to learn hands-on skills and new role-related attitudes, as well as factual content, meant that a variety of approaches, including face-to-face tutoring and direct clinical supervision, were chosen by course developers. In the qualitative data, students referred a great deal to the need for face-to-face interaction for learning some aspects of their new role. They were not given the option face-to-face in the survey because it was anticipated that this would be the preferred learning situation in most cases and it was distance education methods that were being assessed.

Examination of the role of the various factors assessed in this study in student preferences for distance education delivery methods indicates the importance of comfort with technology and technological reliability. Technological breakdown was a frequent and frustrating experience. In a demanding program where time was of the essence, these busy women reported that they put a premium on reliability of delivery methods. This emphasis by the learners is reflected in the stronger correlation found between lack of technical difficulties and preferences for delivery methods than between learning style and preferences. Students reported that they made adaptations if the presentation of material did not match their learning needs. Comparison of preferences, approaches used, and academic success proved to be impossible because all the students who gave permission for access to their grades had done so well in all courses that there were no significant differences. However, if students could not access the material, if the technology broke down, or if the technological problems prevented good discussion, the students were not happy with the method of delivery. This valuing of reliability may account for the frequent choice of print-based materials. These are reliable, portable, and allow self-selection of learning time. CD-ROM was also liked because it was reliable and use of material and timing could be flexible. Previous experience with delivery methods before the program began did not seem to be a major factor in the preference for CD-ROM and dislike of audiotapes and audio-teleconference, but, from student reports, seems to have played a role in the low preference scores for computer conferencing.

The anglophones perceived video-teleconferencing as the next best thing to the face-to-face class with the professor, especially for skill development. However, their experience was extremely limited as it had not been used in the PHCNPP and 79% of them had no previous experience with it. The francophones’ enthusiasm was moderated by their experience of the realities of jerky, unclear images and difficulties getting on-line and interacting, but they still valued the similarity to a face-to-face class.

Anglophones made several comments about the production quality of audio- and videotapes used in the program. Audiotapes were of audio-teleconferences. The videotapes were made by the staff of the program and were usually lectures by experts. Students who are used to broadcast- quality production values found that amateur materials detracted from their ability to learn. As web pages become more sophisticated and students come to distance learning with more experience of the Internet, similar problems can be anticipated if professional input is not sought for design of web-based courses. For all media, raising the technical production quality will increase cost, but it may also increase acceptability of the distance delivery method to students.

It was clear from the interviews that participants believed that no one delivery method was ideal for all distance education. Students believed that a variety of methods should be used. A mix of approaches would mean that the requirements of different types of content, different approaches to learning and the inevitable breakdowns in the more highly technological delivery methods could be accommodated, and they could have satisfying learning experiences.

The responses of these students point to the importance of considering technological reliability and student experience when choosing distance delivery methods. The choice of print-based materials as the most preferred delivery method across different content areas is a reminder to distance educators not to be seduced by the latest gadgets into forgetting the value of low-technology, reliable, familiar options. However, the students’ frequent choice of other delivery methods demonstrates that there is also value in choosing methods that are a good match with desired outcomes. Whenever possible students should be provided with choices of how they receive distance education. Students are able to learn through a variety of distance methods. It is incumbent on distance educators to consider many factors, including technical reliability, in selecting those that will enhance and not hinder learning.

The authors would like to thank the NODE Learning Technologies Network for their funding of this project and Michael Williams of Assessment Strategies and Femmy Mes for their major contributions to this research.

Andrusyszyn, M.A., Iwasiw, C., & Goldenberg, D. (1998). Computer conferencing for graduate students. Nurse Educator, 23(2), 8-9.

Biner, P.M., Welsh, K.D., Barone, N.M., Summers, M., & Dean, R.S. (1997). The impact of remote-site group size on students’ satisfaction and relative performance in interactive telecourses. American Journal of Distance Education, 11(1) 23-33.

Cragg, C.E. (199l). Nurses’ experiences of a distance course by correspondence and audioteleconference. Journal of Distance Education, 6(2) 39-57.

Schutte, J.G. (1996). Virtual teaching in higher education: The new intellectual superhighway or just another traffic jam? Unpublished manuscript, California State University

Betty Cragg is the Director of the School of Nursing at the University of Ottawa. She is actively involved in providing distance education for nurses and conducting research into their reactions to distance education delivered by a variety of delivery methods. Her e-mail address is bcragg@uottawa.ca.

Mary Anne Andrusyszyn is an assistant professor in the School of Nursing in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Western Ontario. She has been using distance technologies, particularly computer-conferencing, in her teaching and learning since 1991. Her e-mail address is maandrus@julian.uwo.ca.

Jennie Humbert is the Eastern Region Co-ordinator of the Primary Health Care Nurse Practitioner Program, an educational consortium of 10 universities in Ontario. She is responsible for distance education in the anglophone program. Jennie has presented at the two CADE conferences on the distance delivery of this program and been involved in other distance education research. Her e-mail address is jhumb@village.ca.

ISSN: 0830-0445