Elizabeth Stacey

VOL. 14, No. 2, 14-33

The study described in this article researched the process of collaborative learning that occurred when postgraduate students studying a Master of Business Administration (MBA) program used computer-mediated communication (CMC) as a means of small-group and large-group communication. It reports a largely qualitative study of groups of students learning collaboratively while living remotely from their university campus. The main objective of the research was to observe and document the effects of the use of the computer-mediated group conferences on the group interaction of the students and to record their use and perceptions of the effects of the use of computer-mediated communication in their learning process.

Cet article décrit une recherche qui porte sur le processus d’apprentissage collaboratif observé chez des étudiants inscrits à un programme de maîtrise en administration des affaires (MBA), qui ont utilisé la communication médiatisée par ordinateur comme moyen de communication en petit groupe et en grand groupe. Il décrit une étude qualitative menée auprès de groupes d’étudiants qui, pendant une période où ils ne se présentent pas sur le campus universitaire, doivent mener à distance une démarche d’apprentissage collaboratif. L’objectif principal de la recherche consistait à observer et à documenter les effets des forums de discussion sur l’interaction d’un groupe d’étudiants, à rapporter leur manière de l’utiliser et à définir leurs perceptions quant aux incidences de la communication médiatisée par ordinateur sur le processus d’apprentissage.

In the relatively few years of widespread use of the Internet for tertiary learning, its potential for providing a shared space for students to learn in groups, even though they are geographically dispersed, has been explored with enthusiasm (Bullen, 1998; Thorpe, 1998). The Internet has helped to remove the isolation of learning at a distance for off-campus students and even made it possible for them to join on-campus students in virtual campus environments (Stacey, 1998). Researching the type of learning that occurs in such an electronic environment has become increasingly important in helping us understand the most effective ways of using online technologies in tertiary programs worldwide. It has also provided a theoretical rationale for understanding the effectiveness of this learning.

The study described in this article researched the process of collaborative learning that occurred when postgraduate students studying a Master of Business Administration (MBA) program used computer-mediated communication (CMC) as a means of small-group and large-group communication. It reports a largely qualitative study of groups of students learning collaboratively while living remotely from their university campus. The main objective of the research was to observe and document the effects of the use of the computer-mediated group conferences on the group interaction of the students and to record their use and perceptions of the effects of the use of CMC in their learning process. At the time the study was implemented, a theoretical framework for collaborative learning in an online environment was only beginning to emerge in the literature (Garrison, 1993), and the research study provided results that supported and extended a theoretical framework from the perspective of social constructivism. This article describes the research study and its results in such a theoretical framework, as well as discussing the implications these have for distance education.

Using CMC with distance learners was seen from the early days of its introduction as having the potential to change the nature of distance education, with an ideal of “a collaborative respectful interdependence where the student takes responsibility for personal meaning as well as creating mutual understanding in a learning community” (Garrison, 1993, p. 17). Researching the use of CMC from this stage of the technology’s use, Mason and Kaye (1990) described computer conferencing as defining a new paradigm in distance education that can provide enhanced opportunities for dialogue, debate, and conversational learning and the potential for a real sense of community with access to other students’ experiences and opinions. They predicted that CMC use would develop a potentially new type of learning community that would provide a space for collective thinking and access to peers for socializing and communication. This prediction is beginning to appear to be affirmed in the widespread use of computer conferencing in tertiary programs (Naidu, 1997; Stacey, 1997; Oliver & Omari, 1999; Jonassen, Prevish, Christy, & Stavrulaki, 1999).

Harasim (1990) described the greatest strength of online education as its ability to facilitate interaction and saw the strength of CMC in group activity. The social, affective, and cognitive benefits of peer interaction and collaboration, which had previously been possible only in face-to-face situations, were now possible with the mediation of computer communication. Hiltz (1994), in listing the ways the virtual classroom (one that exists in interlinked computers) improved access to education, referred to flexibility of student location and time and claimed electronic conferencing as the ideal space for self-paced, active, and collaborative learning “in a peer-support and exchange environment” (p. 12).

Garrison (1993) approached the field from what he terms a cognitive constructivist approach to learning theory where “learners attempt to interpret, clarify and validate their understanding through sustained dialogue (i.e., two-way communication) and negotiation” (p. 202). As a medium for collaborative learning, computer conferencing was considered appropriate because it provided more opportunity for “reflective and thoughtful analysis and review of earlier contributions” (Kaye, 1992, p. 17) than in a face-to-face seminar where a contribution may be missed forever. Harasim and her pioneering colleagues (Harasim, Hiltz, Teles, & Turoff, 1995) repeated and supported conferencing as an ideal environment for collaborative interaction. They stated,

These shared spaces can become the locus of rich and satisfying experiences in collaborative learning, an interactive group knowledge building process in which learners actively construct knowledge by formulating ideas into words that are shared with and built on through the reactions and responses of others. (p. 4).

Henri and Rigault (1996) described this medium as a framework for true collaborative group work in distance education. They saw CMC providing more intense communication than face-to-face groups, where the lack of social pressure and the greater freedom to express their views without struggling for “the right of audience” (p. 10) enabled participants to react to the content, and not the author, with more reflective and effective communications.

These researchers and writers have described the potential of the medium as an interactive environment that would enable collaborative group learning and would change the nature of distance education from an autonomous, isolated experience to a potentially social constructivist environment. In the years that the Internet has come into more widespread use for tertiary learning, online collaborative learning has become more commonly accepted as an effective strategy that is now made possible by the technology. Social constructivist theory has also begun to be accepted as a theoretical perspective for explaining the effectiveness of collaborative learning in an online environment to the extent that Kanuka and Anderson (1998) claim it is “currently the most accepted epistemological position associated with online learning” (p. 60).

To explore the possible effects of using CMC technology in distance learning, this study was developed to explore how groups used a computer-mediated environment and how the groups shared the online environment for group learning. The proposition investigated was that the use of CMC could provide a group conferencing context that would facilitate and enhance learning at a distance. It was anticipated that the medium could provide students with a means of developing and sharing their construction of knowledge of the course content in a collaborative learning environment. This was framed from a constructivist perspective, the idea that people construct their own understanding by actively processing content in order to establish their own meaning. The social nature of cognition as theorized by Vygotsky (1978) provides a basis for learning requiring social interaction, because Vygotsky viewed learning as a particularly social process with language and dialogue essential to cognitive development. Through Neo-Vygotskian research (Forman & McPhail, 1993), such a social basis was seen as influential to a person’s construction of knowledge, and CMC was viewed as a facility for learner interaction. The provision of a means of dialogue in a community of learners was of major importance to the way the study was designed. Knowledge was perceived as a dialectic process in which individuals tested their constructed views on others and negotiated their ideas.

In a distance education context, a course that provides a means of regular group communication through electronic communication and has a defined purpose for group interaction establishes a means of developing a socially supportive environment for students often remote from one another and the campus. Such a group-supported environment is conducive to effective adult learning (Foley, 1995; Knowles, 1990) and provides an environment for students actively to construct their own knowledge through their understanding of the concepts and expressing the language of their new knowledge community. Studies that evaluated CMC use in course units describe positive responses by students (Mason, 1990; Hiltz, 1986; Eastmond, 1994), but the literature lacked deeper, qualitative studies that would provide more detail of the learner’s perspective on how and why the electronic environment could be effective for group learning. Although Burge (1994) and Eastmond (1994) remedied aspects of this gap, few studies provided a clear contextual story of small-group learning in this electronic environment.

This study was developed to explore the possible effects of using CMC technology in distance learning, how groups used a computer-mediated environment, and how the groups shared the online environment for group learning. In particular, the research questions driving the study were: How did the groups use the computer-mediated environment provided? How did the groups share the CMC environment for group learning? What was the nature of learning in this environment? How did the computer-mediated environment provide a socially supportive environment for learning?

The CMC context was researched as an ethnographic study. This type of qualitative, naturalistic approach enabled the participants in the sample groups to be studied in what was defined in this study as the natural context of group conferencing. The method enabled the participants to communicate electronically with the group and with the researcher and to use the electronic context as a data-gathering medium for sharing their perceptions and attitudes to the developing learning process. Hammersley (1990) defined the broad characteristics of ethnography as being usually a small-scale study of people’s behavior in a single setting or group in everyday contexts, not in experimental conditions. Data were gathered from a range of sources, including observation and informal conversation, and were gathered on as wide a front as possible.

In the case of an electronic group context the communication behaviors were studied using three main sources of data as described below.

Interviews—in-depth, before and after the study. Two individualized interviews with each of the student participants, before and after the period of electronic observation, provided the main source of data, particularly about their other types of nonelectronic communication. These interviews sought the participants’ accounts of their communicative behaviors, their reflections on their collaborative learning experiences, and their perceptions of the experiences, attitudes, and beliefs of the group (the electronic learning community) to the cultural context of their electronic environment.

Electronic observation: transcripts of conferences and questions to group conferences. An analysis of the archived electronic conference text was undertaken. Frequency, types, and content of communication were gathered. Questions about their group learning experiences were directed to the data groups through the computer conferences during the study.

Usage statistics of the electronic system were collected each month for each student, resulting in a quantitative record of the range of electronic uses and the timed intervals of logging on to the system. This provided data even if the participant left no written comment on the conference.

If the aim of ethnography, as Shimahara (1988) claims, is to report the culture studied in sufficient depth and breadth to enable one who has not experienced it to understand it, then such a method with its multiple strategies of data collection was appropriate for exploring the culture of electronic group collaboration. It described the electronic learning process and community in detail using the participants’ words and text to create a picture that should provide a range of data for understanding. The approach also provided means of observing the electronic interaction and participants’ view of the process without overtly affecting the type of communication that was occurring. The holistic approach of both qualitative and quantitative data gathering meant a multi-instrument approach with a focus on uncovering the participants’ understandings, motives, purposes, perceptions, interpretations, and beliefs. The electronic environment was a natural context of inquiry, not modified or contrived, a “context in progress” (Shimahara, 1988, p. 77).

The research involved three groups of students (totaling 31 part-time students) studying for their MBA degree by distance education, which had a predetermined structure of syndicate groupings that students were expected to join for course learning and assessment, which were established during their weekend of orientation sessions at the beginning of the program. Their compulsory group interaction was implemented through the use of the university’s CMC system, at that time a university-developed text-based system that provided communication software for e-mail, conferencing, and Internet access called Tutorial and Electronic Access System or TEAS. The groups were based in a diverse range of workplaces and geographical locations in three states of Australia remote from the delivering university location. This was purposive sampling with groups deliberately spread geographically to ensure that the students needed communication technology to facilitate their interaction. The gender balance of the groups represented the course population with more males (21) than females (10). Grouping was even more representational by chance than design in this study, as the groups also selected their own main mode of communication and represented each combination of electronic usage. One group used conferencing as a central form of communication combined with local meetings; another group used only local meetings; and the third group, with no chance of local meetings due to remoteness from one another, was dependent on communication technologies.

The groups were studied over two semesters of the first year of their MBA program with the study particularly focusing on their Business Economics course in the second semester of the academic year. This subject required them to work together collaboratively on two weekly tutorial tasks that were submitted as a group answer after individual input and discussion by the group, and a case study task that also required a group submission.

The content of the tasks was relevant to the workplace and not set within the boundaries of a theoretical context only. The tasks adhered to the constructivist principle that learning is not context-free, but must be situated in a real-life context so that the learner thinks as an expert in the field would do (Bednar, Cunningham, Duffy, & Perry, 1992).

Bruffee (1993) stated that a student’s individual writing is his or her means of joining the knowledge community. If assessed this way the student is reminded of “the responsibility to contribute to that community, to respect the community’s values and standards, to help meet the needs of other members of the community, and to produce on time the work they have contracted to produce” (p. 48). Students were examined individually at the end of the semester so that there was such an individual accountability to motivate their group participation.

The study was designed to gather data in depth rather than in breadth and provided a detailed study of the yearlong process of one course use of CMC for group learning. The interviews and posted questions established the students’ initial experience and their confidence with computers and electronic communication as well as their attitudes to and understanding of online collaborative learning. Similar questions were asked of the participants at the end of a year’s study, including queries about their best conditions for learning, the effects of CMC on this learning, and about their perceptions of the group conferencing process.

Analysis of the date was inductive and used the data to discover categories and interrelationships rather than through predetermined deductive hypotheses. Data were gathered, managed, and analyzed into emerging categories and themes with the use of several computer-based methods.

From the data gathered and analyzed in this study, a model emerged of the attributes of collaborative learning that occurred in the electronically mediated group environment. The group processes and tasks in the researched course were found to facilitate the social construction of knowledge in the groups as they used the group conferences as a central communication space. The process of communicating electronically enabled the learners actively to construct their own perspectives, which they could communicate to the small group. Their process of collaborative learning was achieved through a range of collaborative behaviors and through the attributes of collaborative learning and support that are described in summary below and discussed in detail in the following section. Results of student assessment was another indicator of the importance of CMC in their collaborative group learning and is also discussed.

As described above, each conference was tallied and the type of messages categorized. Most messages in each group related to group learning and support, which was defined as messages of commentary on work of members of each group, organizational messages arranging synchronous interaction, and messages sustaining group cohesion and support. Messages with cognitive content often included socially supportive messages and this aspect of collaborative learning is discussed below.

The attributes of the social construction of knowledge that emerged through collaborative learning via CMC are described below. The students’ words explained these attributes, but have been summarized with only representational comments included in this discussion of the analyzed findings. The development of the group process orders the attributes as the students move from responding as interacting individuals to actively socially constructing knowledge as a collaborative group

As adult learners, many of these students were independent and conscientious in their individual study and came well prepared to use the group interaction for clarification and explanation of aspects of their learning. As they constructed their ideas and concepts, the confusion that could arise from their reading or from ideas they found obscure could impede further learning if concepts or minor points were not clarified. The ability to raise such points quickly with fellow group members, which is often preferable to raising them with a teacher or whole group, facilitated their learning.

With a question about an assignment or something and just a few comments about what to do really then just gets you going. So I think it’s just clarifying some points and making sure you’re on the right track. (Sarah)

The groups who used CMC used the conferences to post their answers and ideas for feedback from the others. Comments were posted with the answers to their tutorial questions or their other tasks. These encouraged and anticipated the type of changes that the other students might make and led to discussion on these. Comments and ideas were encouraged and feedback was frequently requested in these messages.

Posted By: greg on small group conference’‘

The elasticity of demand at $40 per barrel is –1.32 or –0.90 I THINK ????????

The students explained the value of the group for sharing others’ perspectives, exchanging ideas, and developing their thoughts in the way that Vygotsky had theorized and in a way that they could not achieve as an individual learning in isolation. CMC provided the means of facilitating access to that group process. They described the process of comparing work and looking at other people’s perspectives with the collaborative group assignment work that the group achieved through the small-group conference. The business economics tasks that required CMC use forced this process even more as they had to learn skills of communicating electronically, and this contributed to, and enabled, more effective learning through active engagement with the economics concepts. As one student commented:

Above all else I think the advantage to when you outline your topic is to be able to broadcast that topic, get other people’s opinions, be able to share your research information and I guess in a sense be able to discuss at length and at their leisure, the areas that you’re working on. (Malcolm)

They had the opportunity to push their understanding beyond their own limits by considering the ideas of others in the group and so developing their individual construction of knowledge and the language with which to express that knowledge.

Learners generously shared their resources electronically, such as researched explanations, literature references, or expert advice, and this was an effective aspect of collaborative learning. Such resources clarified students’ understandings and expanded new ideas and concepts. Other students’ work was also an extra resource for the student working individually as it could be taken in and extended during later group discussion. Students provided access to advice from industry consultants, and the group process enabled this access to be shared and discussed.

A problem often triggered electronic group discussion, for if a student wanted help the group would be their first point of consultation. This is problem-solving that is appropriately situated in a real context with the shared electronic conference less influenced by distracting aspects such as social roles or status, beliefs, and values that affect face-to-face group interaction (Forman & McPhail, 1993). If the mediational medium of the electronic conference did have an influence, this was not an apparent negative influence. When interviewed, the group members expressed a comfort level with their small-group audience, but did describe feeling inhibited about interacting with the larger group conference.

You don’t tend to ask questions in a forum of a huge number of people, because you think, “oh this could be a stupid question.” (Jemima)

The CMC discussion meant that the group provided students with the means of clarification or changing of ideas as they formed them. The group discussion affirmed or negated their construction of concepts, providing a means of extending ideas beyond the level they can manage individually “to the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86). In this case adult meant an expert in the knowledge community of this study of all adult participants.

Oh, it always helps me to tell them what I think, then they can sort of say “well no that’s not right” or else just giving you support along the way. (Sarah)

As learners, the study’s participants were in the transitional phase of moving from their current knowledge community to the language and community of peers who understood and discussed economic concepts. The small group provided a comfort level in this transitional zone as they constructed their new knowledge, and the computer conference provided an ideal opportunity to write new ideas and language. One student who particularly felt the isolation of not having electronic access discussed learning the language of the new knowledge area as an aspect that needs other people’s perspectives. The chance to learn and practice the terminology and concepts of the new knowledge community was provided by the collaborative groups, which gave group members the security to learn and practice the new language and ideas (Bruffee, 1993).

Not having this opportunity for electronic communication was perceived as a severe disadvantage to the student:

Terry, group A:

I think it depends on what level you’re expected to reach. If you just need the basics well you can read them yourself. I found that very easy and very entertaining. But certainly the demands on the level that you needed were very extensive and I think you need to communicate with other people on that because a lot of unusual foreign language and styles in there that someone like me coming out of a medical field just hits like a brick wall. And I had to communicate with other people to get the slant on it.

The value of the small group’s role as a secure zone, a transitional phase to the new knowledge community, was recognized by these students. There they could practice their language as they constructed their new knowledge through generating solutions to problems and discussing their perspectives. They admitted fear of committing a message written in this new language to the whole-group space, which represented the understandings of the knowledge community to many of them.

I think with the Economics one I’ve felt a bit like I didn’t know what I was talking about enough to talk on them - You know not quite adequate. (Roxanne)

In order for students to learn collaboratively, the small group was also an important supportive environment. The collaborative behavior the data groups demonstrated are described below.

Posting supportive comments and sharing personal anecdotes and information provided a network of social interaction that underlay the mutual respect and trust needed for a successful collaborative group process. This type of communication seemed to give the students the friendship and sense of belonging that helped to motivate them to apply themselves to their study when they were finding it hard to manage, particularly because of the conditions of studying at a distance. Most students interviewed expressed such comments as:

It makes you feel there’s someone else there, and you’re not sort of sitting all alone out away from contact with other people. (Melanie)

Such socioaffective support was particularly important for students learning at a distance, and this was recognized by the study’s participants:

I think it gives us better contact with our fellow students and it takes away the isolation of distance education. And certainly the group that we had running here in the second semester is a fairly tight knit group now and the interaction with the computer has actually brought us together both from an education point of view and probably socially as well. (Greg)

The problems group members encountered in using CMC seemed to provide a common ground as their groups were formed. Technical hints were often shared with the students who were more technically capable helping the others. The humor and informality of reply in solving these technical problems collaboratively set the tone of the group’s interaction, as well as providing the group with a purpose for interaction and discussion, an important aspect in groups forming relationships.

Posted By: Perry

Title: Re “surprise economics!!”

Congratulations Jill you have finally made it into the electronic superhighway!! Watch out there are many false turn offs!!!

By the time the academic year was ending, group membership had become familiar, secure, and supportive, and members wanted to keep together in their established groups. Group members were trying to continue to study similar subjects so that they could continue their interaction and reduce their isolation. They pledged to keep in touch electronically regardless of course choices.

Commitment to the group’s expectation of their contribution acted as a strong motivator for group members to apply themselves to collaborating online. Having others dependent on them for their part in the group participation made them more responsible about their efforts and deadlines, and such accountability was a powerful motivator to study.

You’ve got demands on you to get in there and look and to keep yourself up to date with what’s happening. (Aaron)

The groups collaborated to organize the required tasks without imposing a fixed structure of roles on each other. The autonomy of collaborative groups meant that they organized roles according to the needs of the group with each changing task and stage. Messages such as the following would be posted regularly by different members:

Once we see the number of questions, we can then decide how to distribute them. I am wondering if the coordinator role would be best suited to the person who is either:

I am hoping that the coordinator can be spared any questions and only coordinates the answers. We won’t know if that is possible until the questions are posted.

I will be in contact.

Electronically yours

Fred

The groups used the group conferences to manage the work and administration of the group interaction. Having a central point of communication that could be read by all group members meant that the group interaction could flow smoothly and expectations of contributions could be clearly flagged, thus avoiding any difficulties. The group conferences were used to ask for assignment and administrative help, to share such information in the group, and to arrange teleconferences or meetings with follow-up postings of information for those who could not be there. The friendly social conversation appeared to provide group cohesiveness in the face of shared concerns.

The course results of these groups in the semester assessment showed clear differences in the level of achievement reached among the groups. The CMC-using groups all received credits and distinctions with only one pass-level student who used conferencing minimally. The group that met face to face and did not use the CMC for group interaction received 6 pass-level results out of nine students. Although other factors were involved, the extra level of collaboration through use of the electronic communication meant that the CMC-using groups communicated in more ways and differently. Their communication on the electronic conference was in text, written at a time convenient to the student when they were able to respond with some consideration of their response. It was posted after they had reflected on other messages posted before them, sometimes with reference to other resources such as reading or consulting with others. All students’ messages were able to be posted for group reading unlike the oral group discussion of the nonconferencing group, which sometimes had time for only a few respondents’ views to be heard.

CMC also had effects on student retention in the study. Of the five students who did not come online at all, two deferred the course by early first semester and one failed and also dropped out of the course. The other two kept current with the electronic communication through reports and summaries from other group members.

The two groups with the most access to interaction not only through CMC, but through telephone calls and meetings, gave them a variety of levels for discussion, sharing of perspectives, and time for reflections on these different ideas. Members of the group who did not use their small-group conference read only the subject-specific conferences and seemed not to have reached a comfort level with communicating in a group electronic conference. If they had used the electronic communication as well as meeting face-to-face it can only be hypothesized that a richer, more reflective communication might have emerged. This group’s members admitted that the group meetings were often about “arranging things,” and if this had been done electronically perhaps more academic discussion would have emerged in the face-to-face meetings. The group’s results cannot be directly attributed to the difference in the nature of the group interaction, but it raises the issue of the additional value for learning that the group conferencing provides--an electronic place for continual discussion and reflective interaction, not for just communication of information.

The study answered the research questions by providing a rich description of the way CMC provided an environment for social construction of knowledge through collaborative learning. The socially supportive environment for learning also provided by CMC was an important aspect of the results in defining the collaborative learning process. In categorizing the data, the conceptual division that was made between the groups learning collaboratively to construct social knowledge and the groups’ collaborative support behaviors was in some ways artificial, as the socioaffective support environment was an essential element in the social construction of learning.

Discussion of computer conferencing in recent years has defined “the degree individuals project themselves through the medium” (Garrison, 1997, p. 6) as social presence and claimed a necessity for social presence to be established if cognitive presence is to be sustained (Garrison, 1996). This study’s findings support such a perspective, as the social relationships maintained online enabled the development of the trust and emotional support that facilitated computer-mediated social conversation and provided the learners with a context and stimulus for thinking and learning.

The establishment of an effective learning environment that included socioaffective collaborative support motivated learners and developed their confidence through sharing discussion of their progress and putting this into a realistic perspective. Technical collaboration provided a means of developing group cohesion and enabled a democratic system of group management, responsibility, and roles. Collaboration motivated students to study effectively and to seek to continue the group collaboration throughout the rest of their course. They had met face to face at their initial orientation residential weekend, and this helped to establish a sense of group cohesion that made their social presence on their group electronic conferences easier to establish (Garrison, 1996). As they collaborated technically, helping each other learn to use the conference environment, they established a level of social presence that enabled the social construction of knowledge to occur.

Vygotsky’s (1978) theory of a “zone of proximal development,” which although developed through observation of children was his commentary and study of the whole human condition, has come to be seen as providing an underlying framework in this area of adult learning in a social context. The concept of zones of proximal development, premised on the theory that the group will contribute more to the learner’s understanding than he or she is capable of constructing individually, provided an explanation for the attributes of effective learning that emerged from the analysis of the data gathered through this study. The different ideas and perspectives expressed by others in their groups were considered by these students as they studied the unit, with expert feedback from tutors to confirm that this expression of their knowledge fitted the new knowledge community they sought to enter. They had the opportunity to push their understanding beyond their own limits by considering the ideas of others in the group and so developing their individual construction of knowledge and the language with which to express that knowledge.

Vygotsky’s (1978) ideas that we think as a function of talking with one another and conversation becomes internalized as thought, means that a socially constructed environment is essential to effective learning, as learners need conversation, whether actual or mediated, for thinking and learning to occur. In the case of distance learning this can predominantly be achieved through technological mediation such as that provided by CMC. Bruffee’s (1993) description of learning as leaving one knowledge community for another is made possible for distance learners through the process of communicating through CMC, which enables such collaborative learning. In this study, students worked collaboratively to reach the knowledge community of their MBA course and, more specifically, the learning community of business economics. This is how the process of learning can be observed, through students who can converse with understanding in the knowledge community they have reached. A transition to an ease of communicating the ideas and language of the new knowledge of economics, as was observed on the electronic conferences and in the collaborative tasks, defined the learning that occurred.

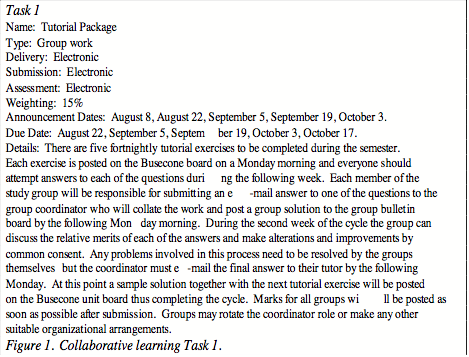

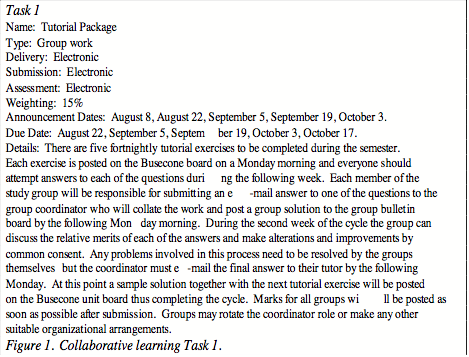

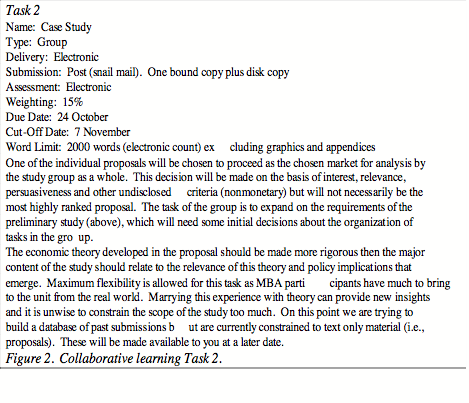

In this study the assessment process was regular and informative (see Figures 1 and 2), and students were in constant contact with teachers as help was needed. If the group expressed doubt about an issue, then there was confidence about asking for expert help as a group rather than as individual students. Some individual students studying at a distance will give up at points of difficulty without the group support provided by such electronic means. Provision of expert advice when it was required or sought was an essential element of the collaborative learning model and was also part of the theoretical framework provided by Vygotsky (1978), who advocated help from a teacher or capable peer as a learner attempted to construct his or her own concepts in a social context. With CMC the teacher could explain what the student needed to know at the point of need. As the electronic medium provided a quick and constant means of seeking feedback on ideas, the chance of going too far in the wrong direction was lessened.

Learners at a distance can often lack the social student network of the on-campus student, which provides them with a comparative perspective of their progress with the course. Feelings of inadequacy about learning can result in poor results and poor retention of distance students in programs (Brown, 1996). During the study’s interviews many students reiterated the importance of the group process in keeping them going when the course became difficult and in providing them with an ongoing network of support.

In the time this research study was undertaken, the size and capabilities of the Internet have grown extensively, and a global online community has developed through increased use of this CMC network. The potential for its use as a means of global adult education has raised discussion about how CMC should be introduced and used, how groups of learners should be organized and facilitated, and how effective its use is in facilitating learning. This study has developed a sound theoretical rationale for using groups to learn collaboratively through electronic conferencing. The small collaborative group’s ability to help students develop social presence online enables them then to be able to work toward a social construction of knowledge. As online technology develops further, the issues of learning and group interaction identified in this study remain consistent and continue to be important to the most effective use of CMC.

This study found that the notion of construction of knowledge in a group context, which is derived from the work of Vygotsky (1978) and neo-Vygotskian researchers, could provide a framework for understanding how the study’s participants learned.

Learning collaboratively through group interaction was found to be achieved through the development of a group consensus of knowledge through communicating different perspectives, receiving feedback from other students and tutors, and discussing ideas until a final negotiation of understanding was reached. In this research study, the interactive communication process was facilitated through the CMC, which established a vehicle for socially constructed learning at a distance.

Bednar, A.K., Cunningham, D., Duffy, T.D., & Perry, J.D. (1992). Theory into practice: How do we link? In T.M. Duffy & D.H. Jonassen (Eds.), Constructivism and the technology of instruction (pp. 17-34). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Brown, K. (1996). The role of internal and external factors in the discontinuation of off-campus students. Distance Education, 17(1), 44-71.

Bruffee, K.A. (1993). Collaborative learning: Higher education, interdependence, and the authority of knowledge. London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bullen, M. (1998). Participation and critical thinking in online university distance education. Canadian Journal of Distance Education 13(2), 1-32.

Burge, E.J. (1994). Learning in computer conferenced contexts: The learner’s perspective. Canadian Journal of Distance Education, 9(1), 19-43.

Eastmond, D.V. (1994). Adult distance study through computer conferencing. Distance Education, 15(1), 128-152.

Forman, E.A., &. McPhail, J. (1993). Vygotskian perspective on children’s collaborative problem-solving activities. In E.A. Forman, N. Minick, & C.A. Stone (Eds.), Contexts for learning: Sociocultural dynamics in children’s development (pp. 213-229). New York: Oxford University Press.

Foley, G. (1995). Teaching adults. In G. Foley (Ed.), Understanding adult education and training (pp. 31-53). Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Garrison, D.R. (1993). A cognitive constructivist view of distance education: An analysis of teaching-learning assumptions. Distance Education, 14(2), 199-211.

Garrison, D.R. (1996). Computer conferencing and distance education: Cognitive and social presence issues. In The new learning environment: A global perspective. Proceedings of the ICDE World Conference. Pittsburgh, PA: Pennsylvania State University.

Garrison, D.R. (1997). Computer conferencing: The post-industrial age of distance education. Open Learning, June, pp. 3-11.

Hammersley, M. (1990). Reading ethnographic research: A critical guide. London: Longman.

Harasim, L.M. (Ed.). (1990). Online education: Perspectives on a new environment. New York: Praeger.

Harasim, L.M., Hiltz, S.R., Teles, L., & Turoff, M. (1995). Learning networks: A field guide to teaching and learning online. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Henri, F., & Rigault, C. (1996). Collaborative distance education and computer conferencing. In T Liao (Ed.), Advanced educational technology: research issues and future potential (pp. 45-76). Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Hiltz, S.R. (1994). The virtual classroom: Learning without limits via computer networks. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Hiltz, S.R. (1986). The virtual classroom: Using computer mediated communication for university teaching. Journal of Communication, 36(2), 95-104.

Jonassen, D., Prevish, T., Christy, D., & Stavrulaki, E. (1999). Learning to solve problems on the web: Aggregate planning in a business management course. Distance Education, 20(1), 49-65.

Kanuka, H., & Anderson, T. (1998). Online social interchange, discord, and knowledge construction. Canadian Journal of Distance Education, 13(1), 57-74.

Kaye, A.R. (1992). Learning together apart. In A.R. Kaye (Ed.), Collaborative learning through computer conferencing (pp. 1-24). London: Springer-Verlag.

Knowles, M. (1990). The adult learner. A neglected species. Houston, TX: Gulf.

Mason R. (1990) Computer conferencing in distance education. In A.W. Bates (Ed.), Media and technology in European distance education (pp. 221-226). Milton Keynes, UK: Open University.

Mason, R., & Kaye, A.R. (1990). Towards a new paradigm for distance education. In L.M. Harasim (Ed.), Online education: Perspectives on a new environment (pp. 279- 288). New York: Praeger.

Oliver, R., & Omari, A. (1999). Using online technologies to support problem based learning: Learners’ responses and perceptions. Australian Journal of Educational Technology, 58-79.

Naidu, S. (1997). Collaborative reflective practice: An instructional design architecture for the Internet. Distance Education 18(2), 257-283.

Shimahara, N. (1988). Anthroethnography: A methodological consideration. In R.R. Sherman & R.B. Webb (Eds.), Qualitative research in education: Focus and methods (pp. 76-89). Lewes, UK: Falmer Press.

Stacey, E. (1997). A virtual campus: The experiences of postgraduate students studying through electronic communication and resource access [on-line]. Available: RMITultibase: http://ultibase.rmit.edu.au/Articles/stace1.html

Stacey, E. (1998). Learning at a virtual campus: Deakin University’s experience as a dual mode university. In F. Verdejo & G. Davies (Eds.), The virtual campus. Trends for higher education and training (pp. 39-49). London: Chapman & Hall.

Thorpe, M. (1998). Assessment and “third generation” distance education. Distance Education, 19(2), 265-286.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. (M.M. Lopez-Morillas Cole, A.R. Luria & J. Wertsch, J. Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Elizabeth Stacey is a senior lecturer in the School of Scientific and Developmental Studies in the Faculty of Education at Deakin University in Melbourne, Australia. She teaches and researches the use of information and communication technologies in distance education, and her doctoral research explored adult collaborative learning online. Her e-mail address is estacey@deakin.edu.au.