VOL. 15, No. 2, 1-16

Discourse constructs the "realities" of educational practice. Web learning and education are being shaped by techno-utopianism, techno-cynicism, techno-zealotry, and techno-structuralism. The Web is an important instrument of distance education or open learning, but developments are impeded by the dominance of techno-utopian discourse. Techno-utopianism straddles a broad political landscape. Some of its silliness arises from the coalition of neoliberal advocates of restructuring and anarchist-utopian social activists, both trumpeting its virtues. Some claim the Web is "second only to death." The authors of this article compare and contrast four discourses by discussing their manifestations in North America and Asia. They identify themselves as techno-structuralists and caution readers about pitfalls associated with zealotry or utopian claims about paradigm shifts, information highway, empowerment, and other trendy terms. They also caution against jumping on the "distributed learning" bandwagon and declaring "distance education" dead and no longer a useful concept.

Le discours construit la « réalité » de la pratique éducative. L'enseignement et l'apprentissage sur le Web sont façonnés par le techno-utopisme, le techno-cynisme, le techno-fanatisme et le techno-structuralisme. Le Web est un instrument important de l'éducation à distance, et de l'éducation ouverte, mais son développement est entravé par la domination du discours techno-utopiste. Ce techno-utopisme influence tout l'éventail des positions politiques. Quelques-unes de ses sottises originent d'une coalition entre les défenseurs néo-libéraux de la restructuration et les anarchistes-utopistes-activistes-sociaux qui clament les vertus de cette utopie. Certains affirment même que le Web n'est seulement surpassé que par la mort. Les auteurs de cet article comparent et contrastent quatre de ces discours en examinant leurs manifestations en Amérique du Nord et en Asie. Les auteurs s'identifient comme des techno-structuralistes et mettent en gardent les lecteurs devant les pièges associés au fanatisme, aux revendications exagérées quant aux « changements de paradigme », à l'« autoroute de l'information », à l'« empowerment » et aux autres termes à la mode. Ils vous mettent aussi en garde contre la tentation d'adhérer trop rapidement au mouvement de l' « apprentissage distribué » et de déclarer le concept de « formation à distance » mort car devenue inutile.

Since the creation of the World Wide Web, educational institutions have been embroiled in discussions about the knowledge-based society, best practices, distributed learning, and empowerment through knowledge and technology. These discussions are nested in discourses that construct “reality.” Discourses are not a reflection of some objective condition, but socially constructed to serve some interests better than others. They arise from relationships between power and knowledge.

Our work is broadly informed by Foucault (1977), who demonstrated how knowledge and power are related. Whenever someone transmits knowledge, it involves power. Whenever power is exerted, knowledge is involved. Foucault’s aim was to attack grand truths and theories, to give free rein to difference and local knowledge, to upset conventional wisdom. He was mostly concerned with how power operates in everyday life, and his primary unit of analysis was discourse. His task was to question rules that permit some statements to be made and others excluded. What rules identify some statements as true and others false? What rules shape the construction of maps or classificatory systems (Paulston, 1996)? What is revealed when an object of discourse (e.g., open learning) is transformed (e.g., distributed learning)? Rules constitute discursive formations. Foucault was not concerned with so-called truth. Rather, the focus was on rules that forbid some statements but permit others.

If power is always linked to knowledge, there is no such thing as neutral education. This is in sharp contrast to the modernist notion that “dispassionate” knowledge arises from objective conditions. There is no objective knowledge and, therefore, all educators are political. Freire (1972) espoused this view, but among many practitioners the notion that they are taking a political position is not easy to accept. From this perspective the Web is not a neutral way of providing education. Although the wires, bits, and bytes are fascinating, the Web is also a discourse that serves some interests better than others (Toulouse & Luke, 1998).

A lot of people love the Web. For people tired of tyrannical teachers, capricious administrators, the fight for parking, crumbling infrastructure on college and university campuses, and other tediums of face-to-face education, the notion of securing education from home is attractive. As a tool for learning it has advantages.

A curious coalition of right and left interests quietens voices that would otherwise raise awkward questions. Neoliberals like the Web because it seems efficient. It nicely fits the exhortation to do more with less. Moreover, it straddles national boundaries and coincides with the interest in internationalizing education in the context of the global economy.

For entirely different reasons anarchist-utopians like the Web because it enables them to subvert unequal power relations that infest much of formal education. Illich (1971), a leading anarchist-utopian, called for the deschooling of society. The Internet and Web exemplify the ethos of deschooling.

With neoliberals and anarchist utopians supporting it, Web learning and education has enjoyed rapid growth. Hence when America Online (AOL) polled 1,001 Internet users in the United States and asked if they would choose the Internet, television, or telephone if marooned on a desert island, only 9% opted for television whereas 67% said the Internet (“Internet users would pick Net over phone or T.V. if marooned: AOL Study,” 1998).

If Karl Marx were alive today he would probably write his magnum opus on Die Information and not Das Kapital (Tehranian, 1990). The first industrial revolution was impelled by capital, whereas at the dawn of the 21st century “information” is affecting all aspects of life. But because capital has information in a firm embrace, and where one goes the other follows, Marx would write about Die Information and Das Kapital. Or, in this context, Das Kapital and Das Web.

It is not our task in this article to analyze the political economy of Web learning and education. We did that elsewhere (Wilson, Qayyum, & Boshier, 1998) by showing how in most parts of the world the telephone system cannot support Web connections. We also showed how American technology (such as browsers and search engines) lead users back to US sites and wondered what this means for small countries. We also do not have space to delve into issues pertaining to the extent to which the Web is appropriate for Indigenous people, women, older people, or those with an ethnocultural background other than Anglo-Saxon. That task was also performed elsewhere (Boshier, Wilson, & Qayyum, 1999).

Rather, our purpose here is to trace the contours of four discourses concerning Web learning and education. After identifying four discourses, our task is to climb Mount Faber in Singapore and Grouse Mountain in Vancouver, adjust telescopes and browsers, and find material that exemplifies each discourse.

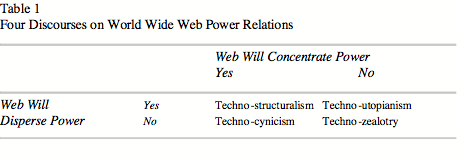

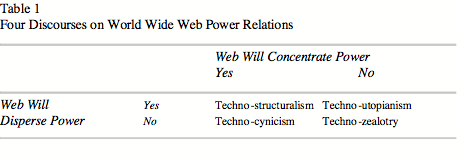

The intense politics of online learning and education highlights the power of competing discourses. At present there are at least four: techno-utopianism, techno-cynicism, techno-zealotry, and techno-structuralism (Table 1). These positions are adapted from Tehranian (1990) and derived from ascertaining the extent to which people believe the Web leads to a concentration or dispersal of power.

Two variables frame most forms of education. In this context the most important is power relations (Boshier, 1994) and in particular the extent to which the Web leads to a concentration or dispersal of power. This is important because writers like Mander (1996) see networked computer technology as a centralizing tendency and form of neocolonialism. In contrast, Rheingold (1993), the editors of Wired magazine, and numerous others see it as dispersing power and reviving participatory democracy. In distance education some see the Web as a dramatic contribution to equity and access. Others regard these claims as utopian and detached from the realities of restructuring, cutbacks, and psychocultural barriers to participation.

Our task in this section is to analyze each discourse shown in Table 1 and identify North American and Asian materials nested in each. This is important because at present policy is in danger of being overwhelmed by utopian thinking. In reading the discourses that follow remember they do not describe objective reality and, therefore, are not buttressed by the kind of referencing (or citation) found in academic work done on a modernist foundation. Discourses such as these are fluid. But even the most atheoretical forms of practice in distance education are informed by one discourse or another. This is not a bad thing provided practitioners understand how intersections between power and knowledge shape individual and institutional behavior.

Techno-utopians are optimists who believe the Web leads to greater access to education. In this discourse the Web:

Paradigm shifts are often explained in racy keynote addresses packed with buzzwords and unproblematized invocations about empowerment. The speaker talks about participation and involvement, but usually has to rush to the next important meeting and has no time for questions. Techno-utopians are often the chief executive officer of important-sounding companies with futuristic-looking logos. They move easily from culture to culture and barely pause long enough to notice local particularities at odds with their techno-utopian vision.

Part of the corporate razzmatazz used by techno-utopians is an unproblematized version of the information highway (or super-highway). The fact this California metaphor makes little sense in most parts of the world is not a problem. Highways are dangerous, create pollution, and are the antithesis of the kind of world needed in the 21st century. Moreover, we are both foot-powered recalcitrants. One of us does not own a vehicle and has difficulty even using public transit. The other lives on a small island without electricity where dirt trails link the chicken run, garden, and house. Even Bill Gates (1995) is not comfortable with the metaphor. “When you hear the phrase `information highway,’ rather than seeing a road, imagine a marketplace or exchange ... digital information of all kinds, not just as money, will be the new medium of exchange in this market.”

We are troubled by conflating computer with material spaces, and for us market means Hong Kong’s Temple Street or being jostled in Bangkok alleys or Singapore of yesteryear. We agree with Druick (1995), who claimed the highway metaphor is “a utopian narrative well-entrenched in the West—namely, progress and salvation through technology and transportation.”

In Asia there is an unlikely concordance of interests between state authorities and social activists—both passionately enmeshed in techno-utopian discourse.

In Singapore IT literacy is considered a “corollary of globalization” (Chia, 1998). The government wants to turn Singapore into a learning society or “intelligent island” with a “semipermeable membrane” to admit needed but keep out unwanted information. According to the Minister responsible (Yeo, 1994), the membrane would be maintained through a “preventative” and an “immunological” approach (“an immune system which fights infection within the bubble. While we can minimize contamination, we cannot expect our environment to ever be germ-free”). Having previously devoted precious energy and resources to keeping unwanted influences (“germs”) out, the membrane idea gave rise to lively discussions about censorship—largely a nonissue elsewhere in the world. Singaporean academics Peng and Nadasrajan (1995) claimed it would be difficult for Singapore to “control information and yet reap the benefits of the information age” (p. 4).

The Singaporean learning society is partly a response to the Asian financial crisis—and very ambitious. Although there were echoes of earlier conceptions of lifelong education, it was not greatly informed by the democratic ethos nested in Fauré (1972). It was not just the use of medical metaphors and invocations about aberrant germs that set it apart. In the Singapore conception, learning is the same as the information society. However, the Asian financial crisis stimulated immense change, and by the turn of the century there were fewer references to membranes and osmosis. Now the Web itself is the metaphor. Hence “we are moving from a hierarchical to a web world ... the power of the state is weakening” (Yeo, 1998). In addition, there was an emphasis on adults learning about information technology so as to instruct their children (Chia, 1998). For lifelong education theorists this is an intriguing development.

In China the authorities are wary of what citizens can learn on the Web, but understand its role in the global economy. Hence despite official uneasiness with 1.32 billion “computer-hungry Chinese” who easily dodge government blocks on servers, China agrees the Net “is the perfect vehicle to transport the Middle Kingdom into the 21st century” (“China Gets Wired,” 1998, p. 16). The authorities seem to think the next great leap forward begins with the initials www, but transmitted contradictory signals by arresting Lin Hai and others for “Internet subversion” (“Chinese crack down on Internet subversion—Dissident’s wife expects guilty verdict,” 1999). In China learning and education on the Web might seem like a modernist and futuristic utopia, but the road ahead seems paved with familiar, contradictory, and repressive intentions.

Although activists in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and elsewhere appreciate the opportunity to build solidarity links and learn from the Web, the Asian enthusiasm for bypassing “official” news and educational agencies is unrivaled. The fall of Suharto in Indonesia, the arrest and trial of Anwar in Malaysia, continuing strife in Burma, and various Internet-related arrests in China evoked passionate proclamations about the democratizing potential of learning and education on the Web.

In Malaysia, the scene of much Internet action, after the arrest of deputy Anwar Ibrahim, it was claimed “electronic discussion groups crackled with debate ... Anwar’s supporters ... stormed onto the World Wide Web ... More than a dozen new websites with titles like Voice of Freedom and Where is Justice sprang up almost overnight” (Erickson, 1998a, 1998b; “Malaysians Are Turning to the Foreign Net Media for Anwar News,” 1998; Politics.Com, 1998). Similar enthusiasm for the utopian idea of leapfrogging over censorship rules also occurred in Indonesia where the Warnet (Internet café) made learning from the Web possible for those without a computer or phone. In Hong Kong, where the notion of superhighway makes little sense, in the best Bruce Lee tradition those using the Internet to foster free speech were dubbed “wired warriors” (Erickson & Law, 1998, p. 47).

Techno-cynics do not believe the Web is a wired utopia for learning and education—or much else. Instead, it will lead to an concentration of power. Techno-cynics are realists, distrust corporatism and the commodification of education, and regard globalization as a code for Americanization. In this discourse the Web:

A Latin American manifestation of this discourse is found in the work of celebrated playwright and novelist Dorfman (1998) who believes that being too connected may deprive people of humanity. Technology itself is not bad. The problem is in the way it constructs relationships. By obscuring pain, technology organizes relationships so as to undermine humanity. Hence corporate executives once went to the maquilladora on the Mexico-US border and saw female workers with swollen legs. Now they click onto the triumphalist company Web site and avoid eye contact with the afflicted.

A disturbing part of the techno-cynic position is enunciated by Mander (1996) who argued that economic globalization involves the most fundamental redesign of sociopolitical and economic arrangements since the industrial revolution. Advocates and beneficiaries of the new order (free trade, deregulation, restructuring) use computers not to empower communities, as techno-utopians would claim, but as a tool of financial exploitation.

Computer technology may actually be the most centralizing technology ever invented, at least in terms of economic and political power. This much is certain. The global corporation of today could not exist without computers. The technology makes globalization possible by conferring a degree of control beyond anything ever seen before. (p. 12)

In the old days this kind of globalization was called colonization.

Noble (1995, 1997, 1998, 1999) is a leading North American exponent of techno-cynicism. He claims that online courses will lead to commercialization of higher education, the loss of faculty independence, a second-rate “shadow cyber-education,” and virtual universities with perhaps no faculty whatsoever.

Much cynicism has been stirred up by claims about mega-universities (Daniel, 1996) and the notion of consigning seasoned educators to the “dustbin of history” (Noble, 1998, p. 1)—sacrificed in the name of economy and efficiency. Noble claimed that “far sooner than most observers might have imagined, the juggernaut of online education appears to have stalled” as has the “ideological bravado” of those advocating distance learning. Hence, although 5,000 students were expected for the opening of the Western Governors virtual university, after considerable expenditure only 10 showed up. None of this was sufficient to curtail the aspirations of the University of Auckland, New Zealand, which despite crumbling infrastructure joined Murdoch’s News Corporation to launch an “e-varsity” (“Auckland to launch e-varsity,” 2000).

In the US access to the Web appears to depend on race. According to a study done by Hoffman and Novak (1998) in late 1966 and early 1997, 44.3% of white and only 29% of Black Americans owned a home computer. In households with incomes of $40,000 or less, white people were six times more likely than Black people to have used the Web in the week before the survey. Perhaps more worrying was the fact that 73% of white college and high school, in contrast to only 32% of Black students in the same settings, owned a home computer. The authors claimed the difference persisted even when the effect of household income was controlled. By the year 2000 the so-called digital divide had created serious potholes in what had previously been touted as a smooth, seamless, and navigable information highway.

Another manifestation of techno-cynicism arises from the tendency of the Web to promote a conservative view of education. There is much more to education than filling empty vessels or, in Asia, producing “stuffed ducks.” Despite fretting by anxious parents, the issue is not whether students cruise the Net for pornography, waste hours chatting with friends, or play games. What ought to trouble them is the fact too many distance education technologies deliver information without raising appropriate questions.

The problem with the Web is that it causes people to think of education as an information-transfer process. “We are building an educational system on the assumption that our minds are a lot of hard drives that can simply be filled up with data” (Ott, 1998) There is an empirical basis to these claims because, as Boshier et al. (1997) discovered in their survey of Web courses, most are information-transmittal oriented. Dirkx (1997) was adamant about this matter and argued that much practice is founded on a techno-rational view that emphasizes objective and literal rather than subjective and imaginative interpretations of the world. For him adult learning should encourage participatory, mythic, and imaginative ways of knowing. He wanted forms of teaching that nurture and care for the soul.

In Asia techno-cynicism resides as much in official as in lay (or academic) circles. Sometimes cynicism is expressed in technology crackdowns. For example, when Malaysia witnessed a passionate embrace of the Web as an instrument of political resistance, official media issued warnings about the heavy price to be paid for openness. For example, Ahmad (1998) claimed that although Web sites criticizing the government were a “growth industry,” they exact a “heavy price” by creating rumors and spreading “false” (i.e., not officially sanctioned) information.

When a hostile government wishes to erode the Web as an instrument of political resistance, it does so by creating a chilly climate—by alluding to the possibilities of identifying and dealing with miscreants. It was developments like these that led futurist Toffler (1998, who had previously applauded Malaysia’s attempt “to create a Silicon valley in a country that 30 years ago was primarily exporting rubber, timber and tin”) to warn that Internet and related developments cannot occur in a “climate of political fear.” Silicon valley has a pronounced libertarian culture “generating endless innovations and whole new industries.” These cannot occur in “the presence of political repression.” Throughout Asia the urge to regulate the Internet appears to run counter to fostering sophisticated and widespread use of the Web for learning, education, and building vibrant civil societies.

In developing Asia, despite techno-utopian talk of paradigm shifts, there are only roughly 9.8 million people online: a mere 0.3% of the population (Erickson, 1998a). Hence, although the traditional rivalry between Hong Kong and Singapore played out in the contest to establish “infoports,” and the leadership in China surfs the Web while arresting those using it to organize resistance to the Communist party, what is happening does not constitute an information explosion or a paradigm shift.

Techno-zealots often appear naïve and are tiresomely upbeat. Whether the Web concentrates or disperses power is not an issue. Power relations are irrelevant because technology has inherent value irrespective of how it is used. In significant ways technology is neutral. Techno-zealots are typically consultants or academics with few theoretical pretensions and a vested interest in cultivating corporate interests or others who control research and development grants.

Techno-zealots enthuse about convergences, paradigm shifts, and the galaxy of wonders lying at the intersection of telecommunications and computers. These people usually live in affluent cities with sophisticated infrastructure. Some of the most intense zealots are people with long experience in distance education and supposedly a sophisticated understanding of the loneliness and needs of the long distance learner.

In the techno-zealotry discourse:

Claims associated with techno-zealotry are significantly detached from the material realities that construct the life of those living in the urban areas of North America, let alone other parts of the world, including rural landscapes, where information technology is nowhere to be seen. Zealots are found in all parts of the world, not just in Palo Alto and Cambridge, Massachusetts.

This is what an Indian-born writer (Pitroda, 1993) said in the Harvard Business Review. Information technology “ranks second only to death.” It can overwhelm “cultural barriers ... economic inequalities [and] compensate for intellectual disparities. High technology can put unequal human beings on an equal footing and that makes it the most potent democratizing tool ever devised” (p. 24). Contrast this with Leonard’s (1998) impressions on arriving in Soweto, South Africa.

I have little patience for the marvelous promise of Web-based multimedia at the best of times, but in a country where the number of people without phones is growing faster than the number of people with them, the prospect of bandwidth intensive Web applications seems downright criminal. (p. 1)

Techno-structuralists—including hesitant optimists and pessimists willing to give the Web a try—are not interested in whether it is good, bad, or neutral. They do not believe the Web will either concentrate or disperse power. What happens depends on how the Web is deployed. Techno-structuralists are mostly interested in institutional forces or the social context wherein the Web is used.

In the techno-structuralism discourse there are questions about:

The centerpiece of this discourse is how technology is used. As Galtung (1979) noted,

A naïve view of technology sees it merely as a question of tools—hardware—and skills and knowledge—software. These components are certainly important, but they are the surface of technology, like the visible tip of the iceberg. Technology also includes an associated structure, even a deep structure, a mental framework, a social cosmology, serving as the fertile soil in which the seeds of a certain type of knowledge may be planted and grow and generate new knowledge ... Tools do not operate in a vacuum; they are man-made and man-used and require certain social arrangements. (p. 6)

Another good example of techno-structuralist thinking is Franklin’s (1996) claim that information per se, particularly that which “has nothing to do with anything ... and [resembles] a civic landfill” does not necessarily lead to social change. She distinguishes knowledge from action and claims political and corporate elites “have no intention of [doing] the right or appropriate thing.” Although the Web can facilitate vertical and horizontal communication, more information does not by itself lead to desired action. It is a question of who is doing what to whom and why?

Other questions informed by a techno-structuralist discourse concern who uses the Web. Using Wired magazine as data, Millar (1998) claimed that the Web primarily serves wealthy, white, male techno-enthusiasts by dishing up a mixture of libertarianism, cliquey techno-gabble and hyper-macho men (“Rich Men Dominate Cyberspace,” 1998). She claims that in a world where two out of three illiterate people are women the “world wide network of netziens” will be mostly white and male.

Having continually repositioned ourselves in these four discourses, now we have to nail our flag to the mast. These are not four equal-sized discourses. At present discussion is dominated by techno-utopianism (particularly in government and business circles), with techno-structuralism informing sidebar academic exchanges. Techno-zealotry and techno-cynicism are found in most places and create an important backdrop for policy formation and practice. Zealots are tiresome, but cynics raise important points not yet adequately answered by those touting the Web as utopia.

It is wasteful to construct Web learning and education as a paradigm shift and thus demean earlier forms of distance education. Errors of earlier forms of correspondence and distance education are being repeated on the Web. But more important, much of the historic concern for off-campus learners manifested by distance education is now being ignored. In our view the continuities between earlier and contemporary forms of distance education outweigh the discontinuities. Hence this is not a good time to shove aside the experience of pioneers like Pitman, Perry, and other architects of distance education. Moreover, distance education is not dead, although its practitioners should be infuriated by advocates of distributed learning. These are mostly face-to-face people who a few years ago had no interest in off-campus learners, but now claim these learners are their business (“therefore, why do we need an open university?”).

The Web has immense potential. But discussion about it is too often built around false binary oppositions—many planted by techno-zealots, techno-utopians, or grant-seeking academics. We are not willing to jettison older forms of distance education or endorse the utopia wherein the solitary learner traipses home to his or her computer or an Internet café. Nor are we enchanted by slashing music and art programs to pay for Web connections.

In summary, discourses on technology construct the “realities” of practice. Discussions concerning Web learning and education are mostly informed by a techno-utopian discourse that promises more than can be delivered. This is a particular problem for developing nations that are hard pressed to maintain a minimal infrastructure for traditional forms of education, let alone the kind of sophisticated technologies needed to secure access to the Web.

In order to compare and contrast the four discourses presented here, we deliberately repositioned ourselves. But in the midst of this repositioning we prefer to sail under the flag of techno-structuralism. For us there is more to the Web than pretty graphics and the ability to access information in distant locations (Boshier et al., 1997). We are disturbed by US hegemony (Boshier et al., 1999) and have reservations about techno-zealot or techno-utopian proclamations about the inevitability of education and democracy arriving at the end of fiberoptic cable.

We welcome, use, and celebrate the Web. But our chief concern is the context in which it is used, who is doing it, and why. Our other aim is to reinforce the legitimacy of traditional forms of distance education and the historic preoccupation with nontraditional learners. In our view, these learners are too important to be set adrift in some shaky and overstated utopia. In all the excitement about the future of distance education, this is not a good time to jettison the past.

The material facts of the Web—browsers, search engines, and pages—are important. But it is also vital that educators watch their words. Terms like paradigm shift, information highway, and empowerment are not innocent. Language is the building block of discourse. When people claim to endorse empowerment, what story lies behind their assertion? And is the Web “World-Wide?” In other words, who is doing what to whom and why?

Ahmad, A.R. (1998, October 27). A price to pay. New Straits Times.

Auckland to launch e-varsity. (2000, May 19). Christchurch Press, p. 1.

Boshier, R.W. (1994). Initiating research. In D.R. Garrison (Ed.), Research perspectives in adult education (pp. 73-116). Malabar: Krieger.

Boshier, R.W., Mohapi, M., Moulton, G., Qayyum, A., Sadownik, L., & Wilson, M. (1997). Best and worst-dressed Web courses: Strutting into the future in comfort and style. Distance Education, 18(1), 327-349.

Boshier, R.W., Wilson, M., & Qayyum, A. (1999). Lifelong education and the World Wide Web: American hegemony or diverse utopia? International Journal of Lifelong Education, 18, 275-285.

Chia, M.O. (1998, February). Development education in Singapore: The impact of information technology. Paper presented to the Asian-South Pacific Bureau of Adult Education Forum on Development Education, Seoul National University, South Korea.

China gets wired. (1998, May 11). Time (Asian edition).

Chinese crack down on Internet subversion—Dissident’s wife expects guilty verdict. (1999, December 5). National Post (Canada), p. A12.

Daniel, J.S. (1996). Mega-universities and knowledge media: Technology strategies for higher education. London: Kogan Page.

Dirkx, J. (1997, October). The illiteracy of literalism: Adult learning in the “age of information.” Paper presented to the Midwest Research-to-Practice Conference on Adult, Continuing and Community Education, Michigan State University.

Dorfman, A. (1998, December). Exile in the information age. Shift Magazine, p. 32.

Druick, Z. (1995). The information superhighway, or the politics of a metaphor. Bad Subjects, 18 [Online]. Available: http://english-www.hss.cmu.edu/bs/18/Druck.html

Erikson, J. (1998a). Asian activists are fighting rough-and-tumble guerrilla wars in cyberspace (2 October). Asiaweek, 24(39), 42-48.

Erickson, J. (1998b) Online—And in fashion. The Internet comes into its own as a catalyst for political change and economic activity. Asiaweek (December 25) [Online]. Available: http://www.pathfinder.com/asiaweek/current/issue/cs6.html

Erickson, J., & Law, S.L. (1998, October 2). The wired warrior: An activist finds free speech costs less online. Asiaweek, 24(39), p. 47.

Fauré, E. (1972). Learning to be. Paris: UNESCO.

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison (A. Sheridan, Trans.). London: Allen Lane.

Franklin, U. (1996). Every tool shapes the task: Communities and the information highway. Vancouver, BC: Lazara Press.

Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Galtung. J. (1979). Development, environment and technology: Towards a technology of self reliance. New York: United Nations.

Gates, W. (1995). The road ahead. New York: Viking.

Internet users would pick Net over phone or T.V. if marooned: AOL Study. (1998, December 17). Financial Post, p. C11).

Harasim, L., Hiltz, S.R., Teles, L., & Turoff, M. (1996). Learning networks: A field guide to teaching and learning online. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hoffman, D.L., & Novak, T.P. (1998, April 17). Bridging the racial divide on the Internet. Science, pp. 390-391.

Illich, I. (1971). Deschooling society. New York: Harper and Row.

Leonard, A. (1998, November 16). Soweto online. Salon Magazine [Online]. Available: http://www.salonmagazine.com/21st/feature/1998/11/cov_feature2.html

Malaysians are turning to the foreign Net media for Anwar News (1998, October 5, Broadcast at 1641 GMT). British Broadcasting Corporation News.

Mander, J. (1996). Corporate capitalism. Resurgence, 179, 10-12.

Millar, M.S. (1998). Cracking the gender code: Who rules the wired world? San Francisco, CA: Second Story Press.

Noble, D.F. (1995). Progress without people: New technology, unemployment and the message of resistance. Toronto, ON: Between The Lines.

Noble, D. (1997). Digital diploma mills: The automation of higher education [Online]. Available: http://www.firstmonday.dk/issues/issue3_1/noble/index.html

Noble, D. (1998). Digital diploma mills, Part III. The bloom is off the rose [Online]. Available: http://communication.ucsd.edu/dl/ddm3.html

Noble, D. (1999). Digital diploma mills, Part IV: Rehearsal for the revolution {Online]. Available: http://www.communication.ucsd.edu/dl/ddm4.html

Ott, C. (1998, August 28). Computers in the classroom promote a conservative vision of education but liberals don’t seem to have noticed. Salon Magazine [Online]. Available: http://www.salonmagazine.com/21st/feature/1998/08/28feature.html

Paulston, R. (Ed.). (1996). Social cartography: Mapping ways of seeing social and educational change. New York: Garland.

Peng, H.A., & Nadarajan, B. (1995, June). Censorship and Internet: A Singapore perspective. Paper presented to the INET ’95 Conference of the Internet Society, Waikiki.

Pitroda, S. (1993.) Development. democracy, and the village telephone. Harvard Business Review, November-December, 66-68.

Politics.Com. (1998). Asiaweek, October 2, 24, 39, 42-48.

Rheingold, H. (1993). The virtual community: Homesteading on the electronic frontier. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Rich men dominate cyberspace. (1998, December 9). National Post, p. B3.

Tehranian, M. (1990). Technologies of power: Information machines and democratic prospects. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Toffler, A. (1998, November). Upheaval dims hopes for Mahathir’s Silicon valley. Technology Suite, 3 [Online]. Available: http://www.asia1.com.sg/bizcentre/techsuite/views1103_1.html

Toulouse, C., & Luke, T. (Eds.). (1998). The politics of cyberspace. New York: Routledge.

Wilson, M., Qayyum, A., & Boshier, R.W. (1998). World wide America: Think globally, click locally. Distance Education, 19(1), 109-123.

Yeo, G. (1994, August). The information age: Its potential and its influences. Speech at the Hwa Chong Junior College 20th Anniversary Celebration Ceremony.

Yeo, G. (1998, May). World Wide Web: Strengthening the Singapore network—From a hierarchical world to a Web world. Presentation to the IPS Conference, Singapore.

Roger Boshier is a professor of adult education at the University of British Columbia. His e-mail address is rboshier@interchange.ubc.ca.

Chia Mun Onn is the President of the Singapore Association for Continuing Education.