This study describes the nature and structure of an introductory educational psychology course in a distance education (DE) medium. Our aims were twofold: to minimize the common problem of isolation among DE students and to restructure the course content from a set of discrete topics to one that attempted to unify the content. To minimize feelings of isolation, students were exposed to structured group activities where they were required on a weekly basis to communicate with one another about the content. Moreover, they were presented with a Ship metaphor that functioned as a means of bonding the students. To help students reconceptualize and personalize course content, we used a series of "Big Ideas" that prompted them to synthesize topics across the domain. Our findings showed that student interactions online involved personal, administrative, and higher-level intellectual exchanges on issues in the field. Moreover, they readily adopted the Ship as their own, giving it a name, and taking on roles for themselves that would help the entire crew. Through structured tasks and online conferences, students assisted one another both within and across groups in discussing ideas and relating them to one another. Recommendations for DE course design and implementation best practices are offered.

Cette étude décrit la nature et la structure d'un cours d'introduction sur la psychologie éducative, dispensé par le biais de l'éducation à distance (ED). Nos objectifs étaient de deux ordres: minimiser le problème commun d'isolement chez les étudiants d'ED et de restructurer le contenu du cours à partir d'un ensemble de sujets séparés vers un seul sujet qui tente d'unifier le contenu. Afin de minimiser le sentiment d'isolement, les étudiants ont été exposés à des activités de groupe structurées pour lesquelles ils devaient chaque semaine communiquer ensemble et échanger sur le contenu. De plus, la métaphore d'un navire a été utilisée comme un moyen de créer des liens entre les étudiants. Afin d'aider les étudiants à conceptualiser à nouveau et à personnaliser le contenu du cours, nous avons utilisé une série de «Grandes Idées» qui les ont incité à synthétiser les sujets à travers le champ d'étude. Nos résultats de recherche ont montré que les interactions en ligne des étudiants occasionnent des échanges personnels, administratifs et de haut niveau intellectuel sur des questions relatives au domaine. En outre, ils ont rapidement fait de ce navire le leur, lui donnant un nom et se donnant eux-mêmes des fonctions qui pourraient venir en aide à l'ensemble de l'équipage. Par le biais de tâches structurées et de conférences en ligne, les étudiants se sont aidés les uns les autres, à la fois à l'intérieur et entre groupes, en discutant des idées et en les reliant ensemble. Des recommandations pour le design de cours d'éducation à distance et au sujet des meilleures pratiques d'implantation sont présentées.

Distance education (DE) courses are increasing in their popularity and changing in their nature owing to the development of technology (Laferriere, 1999). Although one of the goals is to increase accessibility of education to students, it is also our responsibility as educators to raise the quality of education. A concern in distance education is that students are usually faced with the unidirectional transmission of information (even with “interactive,” online courses) and objective-based tests that tap mainly into recall and comprehension (Gutierrez, 2000; Morley, 2000). In turn, this approach leads to students’ inability to deal with real-world tasks that require problem-solving skills, the ability to integrate knowledge including their own experiences, and to produce new insights (Bransford, 1979; Novak, 1998).

Additional problems in DE courses are feelings of isolation, lack of direction and management, and eventually waning motivation (Abrami & Bures, 1996). In an attempt to resolve these social and motivational difficulties or problems, computer-mediated communication (CMC) such as bulletin boards and conferences has been used to increase communication between students and the instructor. However, the communication is often limited to administrative uses (e.g., announcements, clarification, and submission of assignments, Hiltz, 1998). In these circumstances, use of CMC does little to alleviate social and motivational problems or obstacles in the deep processing of knowledge. In this article we discuss how components of a distance education course were designed to foster student interaction and provide relational and critical thinking. Our approach was in line with Bullen’s (1999a) thinking that “creating an interactive online learning environment that promoted critical thinking depended on more than simply creating the appropriate technological environment” (p. 1). In addition, evaluation and performance data are presented.

The design of the distance education course emerged as a result of constructivist and humanistic views of knowledge and our use of collaborative and cooperative learning (Abrami et al., 1995). A common theme among constructivists is that learners must be challenged by meaningful tasks that are suited to the real world and that learners actively construct by using their prior knowledge and experiences to manipulate, relate, organize ideas, and examine alternative points of view (Bransford & Stein, 1993). The teacher’s role in turn shifts from one of dispensing content to one of reconceptualizing ideas, designing activities that are meaningful to students, and facilitating students’ construction of their own and the group’s understanding. In this view teachers provide scaffolds so that learners can ultimately manage their own learning (Stacey, 1999; Weinstein & Meyer, 1991).

To implement these principles in the course, instead of asking students to learn about various “isms” that focus on the discrete presentation of ideas such as behaviorism, humanism, and cognitivism, the instructor1 presented students with key principles in the field of educational psychology referred to as Big Ideas (e.g., we are active learners). These Ideas served to synthesize the content, enhancing content relevance (as learners must draw on their own prior knowledge to establish conceptual relationships) and transfer (Salomon & Perkins, 1989). Furthermore, these synthesizing activities were undertaken using structured, online group work. The design of these activities was guided by the cooperative learning literature, which speaks to issues of responsibility for the students’ own learning as well as that of others (Abrami et al., 1995; Lou et al., 1996; Johnson, Johnson, & Holubec, 1993; Slavin, 1989). According to Becker and Dwyer (1998), “group projects are increasingly essential part of assignments” (p. 1) as group work is part of the working world that students eventually embrace.

We were also guided by humanistic thinking, in particular that learners have various needs, including the need to belong, to interact with each other, and to be part of a community (Maslow, 1987; Stacey, 1999; Vygotsky, 1978). Attention to this need is particularly relevant in the distance education setting in the light of the problems with isolation mentioned above. The use of metaphors is often recommended to help learners feel that they are in familiar surroundings (Collis, 1997) and therefore more likely to anchor prior knowledge and experiences to new ones (Bransford, 1979). In this course the metaphor of a Ship was used to foster students’ sense of belonging to a larger community and to provide a framework for role assignment, identity, and responsibility. This approach also supports the goals of cooperative learning cited above.

The following case explores our use of metaphor, online interaction patterns among both students and teacher, and student reactions to both the content and the instructional strategies. We conclude with a number of empirically supported lessons learned and best practices.

This study reports on an undergraduate section of educational psychology that spanned across two academic terms (Fall/Winter). Students came from a variety of cultural, linguistic backgrounds as well as from different disciplines, were studying full or part time, and were mostly female. The course had one instructor who had taught the course in non-distance education mode and one teaching assistant. Initially 60 students were registered, but the final enrollment in the course was 30 students. Reasons for this decrement were twofold: (a) students were faced with serious technical problems with FirstClass, many being unable to communicate for the first month, which accounted for most of the dropouts, and (b) later students commented that the work assigned to them made them “think” and some were not used to this level of cognitive engagement.

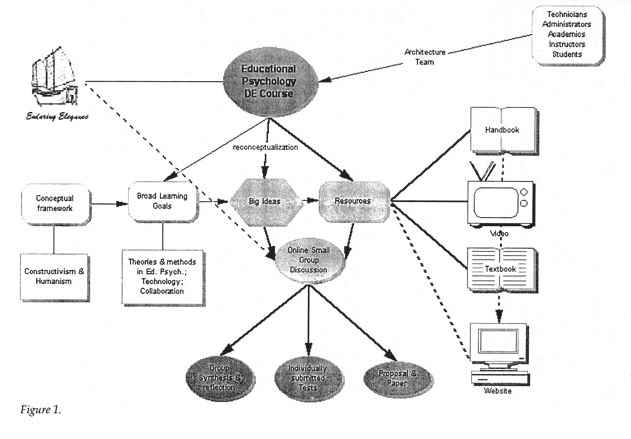

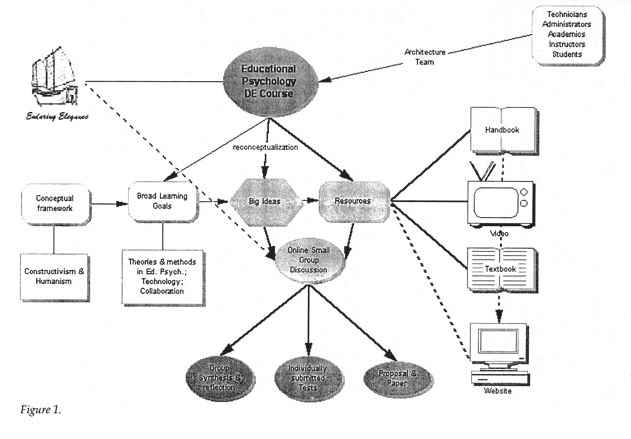

This distance education course was in its second year of pilot implementation. As depicted in Figure 1, the metaphor used in the course was a Ship: the teacher was the Captain, and the students were the Crew, who worked on various tasks designed to be meaningful and integrative. This metaphor was used to represent a voyage during which both student and teacher would meet the challenges associated with learning the content, the technology, and the process of working together. Another reason for this metaphor is that ships are familiar objects and they exude an air of respect, a value that the instructor wished to impart to her students.

Several resources on the Ship would guide their learning (see Figure 1): (a) the course textbook on educational psychology; (b) the videos, which carry the weekly content with discussion and examples of concepts discussed in the course textbook or in the general area of the field, as well as interviews with leading experts (broadcast four times weekly on local TV channels); (c) a student guide that served as the course navigational system, stating the course objectives, course assignments, and schedule; and (d) computer-mediated communication (CMC) software (FirstClass) to support teacher-student and in particular student-student interaction and communication on all aspects of the course.

To help cultivate a sense of community on the Ship, three to five students were placed in randomly assigned groups that remained in place throughout the year (unless some fundamentally irreconcilable differences arose). Using CMC, groups engaged in activities like group discussion, communication with the teacher, and the writing of five synthesis and reflection assignments. Individual group members received credit for the quality of their weekly discussion such as asking questions, providing clarification, elaborating, or revising an idea, and a group grade was awarded to the assignments.

To guide the discussions a new Big Idea was presented every third or fourth week so that students would discuss several theories as presented in their texts and/or videos in relation to the Big Idea. Once presented, these ideas were frequently revisited by both the students and the instructor. Based on these discussions, groups wrote the synthesis and reflection pieces spread across the year. The objective was not only to summarize and comment on the content, but also to critique the ideas and then reflect on them by drawing on their own knowledge, skills, and experiences.

In turn, both discussions generated from the Big Ideas and content from the syntheses and reflections were used to compose the mid-term and final exams. Although students could assist one another for the preparation of these exams, they were taken individually. The exams required the students to apply, synthesize, and evaluate what they had learned using conceptual principles and practical experiences to various problems. Finally, students were asked to engage in a project or research paper. They had the option of doing this together or individually, and most were completed individually.

Multiple data sources were used: student online interactions; a Teacher and Course Evaluation Questionnaire (TCEQ); and overall performance.

The online discussion was garnered by selecting at random two of the seven groups and examining the nature of their interaction patterns. Discussion was divided into three periods of this eight-month course (early, middle, and late). A distinction was also made between student-student, student-teacher, and cross-group discussions. Discussions were subdivided to determine whether there were any differences in quality of interactions over time. Themes were derived from these patterns.

The course evaluation questionnaire consisted of 18 items. Examples of these included: “I was able to get help from my instructor online”; “I developed my ability to respect and care for others”; “This course helped me to relate my own ideas and experiences with ideas and concepts in the course”; “This course helped me to become a more reflective thinker”; “The course tasks and assignments were effective in helping me learn”; and “Overall, I have learned a great deal in the course.” Students rated each question on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 is strongly disagree and 5 is strongly agree.

The results of this study are presented in three subsections: (a) students use of metaphor; (b) online interactions between students, between students and teachers, and across groups; and (c) end-of-course student evaluation and performance.

Most students in our class clearly welcomed and made active use of the Ship metaphor by interacting with the metaphor to suit their needs. This approach is similar to that of Yeoman (1996), whose instructor created a conferencing environment for his students using the metaphor Sam’s Café. Our students participated in naming the Ship; some assigned themselves a role like the Captain’s sexton and sea-watcher; and others modified existing icons (i.e., symbolic folders in FirstClass that students can create) to reflect their understanding of course materials and course environment.

Also, the metaphor allowed students to focus on solutions rather than become distracted by their emotions when things went awry. For example, when things were confusing some students would say, “A storm is coming up ahead,” or when expectations and procedures were still new to them they would say, “I’ll keep a watch for icebergs.”

Alternatively, if some group members had not been heard from for a few days, others would announce that they were looking for “lost crew members.” The experience of not hearing from group members often provoked anxiety for many who kept a more regular online presence. However, thinking of their classmates as lost crew members eased such anxiety and increased their efforts to locate them.

Those who made use of the metaphor as described above were also able to create for themselves a sense of belongingness and community, whereas those who were not able to use coping strategies to address technological and content challenges eventually dropped the course.

The vast majority of students were online at least twice a week, making this component of the course the centerpiece for participation and interactivity. We were also interested in the nature of the online discussions, so we undertook a qualitative method of analysis to categorize emergent themes. Complete transcripts of two randomly selected groups were analyzed. Initial examination was guided by procedures develop by Poulsen et al. (1995) and yielded categories such as “personal, administrative, content, group process.” We included personal interactions because these communications are socially constructed and came into play as the group faced online challenges such as interpretation of one another’s ideas and problem-solving (McLoughlin & Luca, 2000). The use of keyword searches enabled us to refine and quantify the categories. The early period included the first two months; middle, the next three months; and late, the last two months.

The categories that emerged in our analysis of student-student discussions were personal, management of learning environment, administrative, and cognitive (subdivided into asking for clarification, intellectual exchange, and checking for others’ understanding). These categories were clearly present in both samples. To further establish their validity, a keyword search was undertaken to locate similar content in the other five groups, and their presence was verified. Examples of each category are provided below. These categories are reflective not only of cognitive interactions as talked about by Henri (1992) and Stacey (1999), but metacognitive comments.

Early interactions were marked by personal and administrative inquiries as well as more cognitively oriented interactions, especially in how clarifications were requested.

Personal. In personal interactions students talked about their personal lives and feelings. For example, when talking about Big Idea 1, one student said, “I also feel that I am not part of this group since nobody ever responds to my messages and discussions.”

Administration. In reference to administrative conversations, students talked about the status of technology and their reactions to it. For instance, when working on Big Idea 1, one student wrote, “The initial computer intimidation is subsiding ... and I just got the Big Idea One.” On another occasion, when working on Big Idea 2, another student wrote, “I’m glad to see that you were not yelling at me; I must say I got a little worried! That is the challenge of working with a new medium.”

Management of learning environment. This category has to do with clarification of tasks that students need to do for themselves. For example, in working on Big Idea 2, one student wrote to the group, “We should respond to each other’s messages and we will all try to be more aware of this, but I was just pointing out my thoughts, which I thought would be helpful to all of us to enhance the group as a whole. Sorry if you misinterpreted, I did not mean any harm, if anything I want our group to work even better together.”

Cognitive. In cognitive interactions students asked for clarification, engaged in intellectual exchange, and checked for others’ understanding. For example, when working on Big Idea 2, one student asked her group members for clarification, “Perhaps the first video is what’s confusing me, and I’m going to review it again. Any clarification ... you might have, I welcome.”

When working on the same Big Idea several students in the same group were engaged in an intellectual exchange. One student started: “I just wanted to bring the concept of `self-efficacity’ into the discussion.” Another student replied:

[Name of student], you are making a lot of sense. I don’t know if you watched the video yet but in the video they say exactly that. They say that a teacher should not introduce new games or tasks to challenge the children. Instead the teacher should leave a toy or game long term so the children can be successful at it and then try something new. Also I believe that scaffolding also implies that the child should be supported (at their own level) until they are able to learn on their own.

Students also frequently checked with each other for understanding. For example, working on the same Big Idea, one student contended, “I am not sure I see a difference; I’ll have to think about it! What do you mean? A difference in how we challenge them or if we challenge them?”

Although there were still personal and management-of-learning interactions, students placed greater emphasis on the cognitive forms of discussion, samples of which are offered here.

Cognitive. In discussing Big Idea 7, two students were engaged in an intellectual exchange. One student said, “Where I see that learning is genuine is the child is not forced to act in a certain way (like operant conditioning), the child actively thinks through the situations even on small scale modeling.” Another interjected,

Hi! I guess I wasn’t explaining it adequately or perhaps I’m not fully understanding Skinner! It just seems based on reading his theory that learning is done through behavior, however the PROCESS of learning just doesn’t seem as natural to me or as genuine as the social learning theory. I guess I’m having a hard time explaining it?? Help!

Another student said, “So I think that reinforcements are everywhere, in any form and probably that is why I think that both theory are important because in some way they complete each other.”

During this period students continued to check with each other for understanding. For example, one group verified that their communications were accurate. “Am I making sense?” “I guess my point is not really clear, but for now, it’s all my brain can think of ... !!! I will come and check tomorrow!!”

By this time in the course students were involved in many types of interactions as categorized above. In the cognitive interactions they were more active in voicing and discussing their viewpoints. They were also involved in managing their assignments and learning environments.

Management of learning environment.

Now we can start fresh with new ideas to contribute to Big Idea 5. Big Idea 5 is due on March 9th, I believe. That is only about 2 or 3 weeks away. Is anyone interested in taking this one on. Any volunteers????

Another student responded:

Do you mean synthesis no. 5?? Let’s do this as a group, each of us can keep track of specific examples or stuff they want to put in the synth. Maybe we can keep it in the folder you created for the synthesis papers. It might make it easier to write the paper ... just an idea.

Cognitive. Several students in one of the groups were engaged in an intellectual exchange regarding the Big Idea “learning and teaching is enhanced when the learner engages in self-evaluation.” One student commented that she “liked the general idea of teaching children to take responsibility for their own behaviors. The examples in the video were also very representative of the kinds of disruptive behaviors a teacher sees in classes today.” Another in the same group replied:

Hi [Name of students]! Our Big Idea “learning and teaching is enhanced when the learner engages in self evaluation” was clearly demonstrated in this week’s video regarding reality therapy. I thought it very interesting and perhaps a very useful tool for teachers to know ... but I saw where it needed to be practiced in order to reach the desired outcome. I wouldn’t mind learning more about it. I tried practicing it on my 6 yr old daughter today but it didn’t work ... I guess I wasn’t doing it right. I asked her what she was doing (after I noticed she was fighting with her little sister) and she replied bugging my sister ... I asked her if that was accomplishing anything and she said yes since her sister had just broken her pretend fort and she was getting back at her ... I didn’t know how to go any further because I was obviously getting no where with my train of thought???!! The video was good in making us aware that reality therapy which ties into our Big Idea is available to us but I really need to get more info on it in order to feel really comfortable with its success. What are your thoughts?

Bye for now

PS. Hope you have a wonderful Easter holiday!!! I cant believe there is only 2 weeks left with our discussions ... I’m so used to checking in for messages I think I’m going to feel at a loss for a temporary period ... or am I insane???!!!!”

A third student replied,

Hi [you two]! I agree with [name of student] that Reality therapy takes some practicing. When my son was about 1.5 years old I took some parenting classes and learned about I messages etc (also mentioned in our text). When I first started using I messages and trying to reflect back to my son it felt very unnatural but then it became second nature. I think that Reality therapy would become more natural with practice.

Have a good Easter! If you are insane ... then I am too ... we’ve been at this for a while so I think it is only natural that we will feel a little loss not checking for messages. Bye for now.

The student-teacher analysis also yielded the same categories as mentioned above: personal, administrative, managing learning, and cognitive (asking for clarification, intellectual exchange, monitoring student understanding).

During this period the instructor’s communications dealt with providing students with direction as to the procedural aspects of the course so that they could engage in the relevant cognitive tasks.

Managing learning. When students were working on Big Idea 2, the Captain said, “Also, in responding to BIG 2, text, and whatever else, make sure you respond to another too! In addition, do not forget that you are getting points for your discussions (not presentations), so if you hurry, I cannot give points.”

By mid-semester, the instructor was more involved in explaining ideas to students than was the case with the early interactions.

Cognitive. With regard to Big Idea 7, the Captain asked for clarification, “I don’t know if I’m right but when you speak of the `curriculum,’ do you mean only the curriculum, or their pedagogy (which includes the curriculum, but not limited to)?”

Regarding the same Big Idea, the Captain engaged in an intellectual exchange with her students:

I also believe that genuine change occurs when it is meaningful to the learner. In other words, it needs to have value and worth to the person. Also, Paul Pintrich, a researcher in conceptual change, says that people will make change when these changes are fruitful. Who wants to engage in a change when it bears little or no fruit? The “fruits” might be monetary or tangible or simple intrinsic value-more knowledge, greater humanity, etc.

The aim during this period was to remove instructor support so that students could rely on one another to a greater extent than they had earlier. The conversations focused more on cognitive interactions with the students such as asking for clarification and engaging in intellectual exchanges.

Cognitive. In an attempt to prompt a student to elaborate, the Captain contended “Come on [student name]! You can find something to say that will give us a window into your unique way of thinking about cooperative learning and the Big Idea. How about cooperative learning and constructive learning?”

The strengths of having group interaction available online is not only limited to intragroup collaboration; it also encourages intergroup collaboration.2 Students shared online tips for learning, writing, and how to overcome technical problems. Examples of these intergroup collaborations are provided below.

Initially a student addressed members of own group, but when she discovered that they were not online, she addressed the other groups,

It’s me [name of student]. As you can see I’m having trouble sleeping so that I decided to see if any of my members had written ... Nope! Then I decided to check your group out and it looks that you’re also out of luck! Hmmmmmmmm ... good or bad idea??? Anyways good luck and sweet dreams. Don’t forget your gym clothes for tomorrow!

This interaction involved three members from two different groups. One student suggested his “Poker Chip theory” to all groups. The originator of the theory said to another individual in another group,

[Name of student], you bring up valid points. But I also think you are taking the object in a metaphor a bit too seriously. It’s not to take the place of a valid explanation, it’s to help the understanding of a concept that may not be obvious to those learning it ... It doesn’t have to be gambling, I agree, but I’m open to a similar metaphor that works just as well ... suggestions?

Here is another example of across group interaction in intellectual exchange:

Hi [Name of student]. I was going through some messages because there is nothing new in my group (it’s okay because it is the exam, I suppose, but in a way I missed the discussion). You have a very interesting point here. The concept of teaching the child that other ways or other things exist in different cultures is good. It makes the student learn to accept and understand different cultures, values, etc. ... But here is the question that he brings up. He says that it’s good to teach understanding to children, but to what degree?

In addition to online communication, students were exchanging phone numbers and scheduling times to meet with one another to discuss the content face to face and/or to arrange social gatherings with one another and the instructor (this was possible as most lived in the same city). (It is worth noting that students were also provided with a confidential “Pub” to which the teacher and TA were denied access.)

As part of their regular end-of-course teacher evaluation, students were asked to complete the Teacher Course Evaluation Questionnaire (TCEQ). Overall, students were very positive about the course. On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is strongly agree and 5 is strongly disagree, the majority of the respondents (i.e., 71.3%) either agreed or strongly agreed that the course had developed their “ability to respect and care for others.” In addition, over 91% of the students either agreed or strongly agreed that “I was able to get help from my instructor online.”

In reference to the integrative Big Ideas, 100% of the students replied on the TCEQ, that they either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement: “This course helped me to relate my own ideas and experiences with ideas and concepts in the course.” Also, 93% of the students either agreed or strongly agreed that the course helped them to become a “more reflective thinker.” Moreover, 82% either agreed or strongly agreed that the “course tasks and assignments were effective in helping [them] learn.” Students’ online discussion showed that they were relating more than one theory to a Big Idea. Initially this required some prompting from the teacher, but they gradually began to look for commonalties. Indeed they also produced better synthesis and reflection pieces, scoring on average 60% for the initial papers to 80% to 90% for the later ones.

Both the instructor and the students had a successful learning experience with the course. In terms of performance, response to the statement “Overall, I have learned a great deal in the course” on the TCEQ, 66% of the students either agreed or strongly agreed. In support of this perception, the mean overall performance for the course (assignments, exams, etc.) was 73.3% (and a median of 84), scores ranging from 50 to 95. Although a variety of factors led to the extremely wide distribution of scores, the single factor that best “predicted” low achievement was lack of active, quality participation. Because of the integrative nature of the Big Ideas and subsequent tasks, failure to participate directly influenced all other aspects of the course.

This course succeeded in implementing strategies that minimized feelings of isolation and enriched meaningful learning for those learners who overcame the initial communication problems and were willing to undertake the required workload. The forum described above was created to promote meaningful learning in three ways: (a) by having a metaphor that students could relate to; (b) by having continual online group interaction both within groups and across groups; and (c) by having integrative activities that are structured to support and sustain group collaboration.

The use of metaphor gave rise to feelings of belongingness, consolidation of group identity, and a focus on problem-solving. The metaphor also allowed students to become grounded so that they could concentrate on collaborating and solving problems together. Although Yeoman and her colleagues found that her learners abandoned the Café metaphor, our students used the Ship metaphor throughout the course. Three features of our metaphor stand out. First, the idea of a voyage implied an extended time frame—they were in this for the long haul and opted to take on and retain personae as members of a collaborative crew. Second, the metaphor was sufficiently familiar for them to understand, but was at the same time novel and “romantic.” Finally, the concept was reinforced throughout the course by the instructor’s reference to herself as the Captain, signaling an appropriate mix of authority and knowledge on the teacher’s side, and self-reliance or collective accountability on the student-crew’s side.

Group collaboration gave students a venue for offering cognitive support for one another through questioning, elaborating, and summarizing as well as emotional scaffolding for one another (largely represented in our “intellectual exchange” category). Cross-group collaboration gave students wider opportunities to share experiences with one another and to build a greater sense of support and community to draw on as the group needed. This form of collaboration fostered a sense of independence from the teacher. Consequently, the teacher was not solely responsible for their emotional and intellectual well-being. Student interdependence also prevented a common problem cited in the literature: that instructors become overwhelmed with the demand for myriad individual questions.

The structured activities allowed students to operate in a framework that supported meaningful and purposeful learning. The series of integrative Big Ideas prompted students to compare theories, relate them to their own experiences, and synthesize topics across the domain.

Overall the data suggest that it was the combination of the above three factors that enabled our students to develop meaningful learning of the Big Ideas in the discipline.

Methodology. This study offers a revised categorization system for the analysis of collaborative discussions held in computer-based conferencing environments. Data were analyzed not only for type (as found in Stacey, 1999), and metacognition, but over time. The literature on the development of group dynamics describes five qualitative stages, that is, forming, storming, norming, performing, and terminating (Tuckman & Jensen, 1977). Bullen (1999a, 1999b) reported problems with group development, particularly as it related to the time required to form productive interaction. Our data explicitly represent this development: from early, personal communications to increased cognitive ones; to later, synthetic activities. Instructors should be sensitive and accept this developmental evolution in collaboration and withdraw scaffolding only as learners acquire the skills and habits necessary to support higher-level cognitive engagement.

Future research. The results of this study suggest the value of continued exploration of the use of metaphors, structured group activities, and both intergroup and intragroup collaboration to enhance student learning in a distance learning environment. Furthermore, one must attend to the ongoing problem of attrition. CMC lay at the core of this course’s success, enabling interaction arguably superior to that encountered in large-enrollment in-class courses. Early effective technical support is the sine qua non of this approach. Another issue we intend to examine relates to the students who dropped the course due to its heavy cognitive demands. Participation was greater than that typically required in an in-class mode, and the nature of participation vis-à-vis the synthesizing activities appeared to place unanticipated demands on both the time and ability of some students. We intend to study alternative course design and support activities that will provide necessary scaffolding for these students.

An earlier version of this article was presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, April, 2000. The authors wish to acknowledge Christina Dehler as the technical support person for the online discussions. We also wish to acknowledge Stef Rucco for overall administrative support of the FirstClass conference.

Abrami, P.C., & Bures, E.M. (1996). Computer-supported collaborative learning and distance education. American Journal of Distance Education, 10, 37-42.

Abrami, P.C., Chambers, B., Poulsen, C., De Simone, C., d’Apollonia, S., & Howden, J. (1995). Classroom connections: Understanding and using cooperative learning. Toronto, ON: Harcourt-Brace.

Becker, D., & Dwyer, M. (1998). The impact of student verbal/visual learning style preference on implementing groupware in the classroom. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Network, September, 1-9.

Bransford, J.D. (1979). Enhancing thinking and learning. New York: Freeman.

Bransford J.D., & & Stein, B.S. (1993). The ideal problem solver (2nd ed.). New York: Freeman.

Bullen, M. (1999a, October). Technology meets pedagogy in online distance education. Paper presented at WebNet 1999, Honolulu [Online]. Available: http://www2.cstudies.ubc.ca/~bullen/webnet.html

Bullen, M. (1999b, September). Collaborating in the virtual learning environment: Problems, practicalities and potentials. Paper presented to the Primera jornada regional de Informatica educativa y enseñanza virtual, San Jose, Costa Rica [Online]. Available: http://www2.cstudies.ubc.ca/~bullen/costa.html

Collis, B. (1997). Pedagogical re-engineering: A pedagogical approach to course enrichment and and re-design with WWW. Educational Technology Review, 8, 11-15.

Gutierrez, J.J. (2000). Instructor-student interaction. Education at a Distance, 14, 1-16.

Henri, F. (1992). Computer conferencing and content analysis. In A.R. Kaye (Ed.), Collaborative learning through computer conferencing: The Najaden papers (pp. 115-136). New York: Springer.

Hiltz, S.R. (1998, November). Collaborative learning in asynchronous learning networks: Building learning communities. Paper presented to WEB98, Orlando. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 427 705)

Johnson, D.W., Johnson, R.T., & Holubec, E.J. (1993). Cooperation in the classroom (6th ed.). Edina, MN: Interaction Books.

Laferriere, T. (1999). Apprendre en reseau: Une option pedagogigue a l’aube du noveau millenaire. Education Canada, 39, 12-15.

Lou, Y., Abrami, P.C., Spence, J.C., Poulsen, C., Chambers, B., & d’Apollonia, S. (1996). Within-class grouping: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 66, 423-458.

Maslow, A. (1987). Motivation and personality (3rd ed). New York: Harper & Row.

Morley, J. (2000). Methods of assessing learning in distance education courses. Education at a Distance, 13, 1-8.

McLoughlin, C., & Luca, J. (2000, December). Lonely outpourings or reasoned dialogue? An analysis of text-based conferencing as a tool to support learning. Paper presented to the annual conference of the Australiasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education, Brisbane [Online]. Available: http://www.ascilite.org.au/conferences/brisbane99/papers/mcloughlinluca.pdf

Novak, J. (1998). Learning, creating, and using knowledge: Concept map as facilitative tools in schools and corporations. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Poulsen, C., Kouros, C., d’Apollonia, S., Abrami, P., Chambers, B., & Howe, N. (1995). A comparison of two approaches for observing cooperative group work. Educational Research and Evaluation, 1, 159-182.

Salomon, G., & Perkins, D.N. (1989). Rocky roads to transfer: Rethinking mechanisms of a neglected phenomenon. Educational Psychologist, 24, 113-142.

Slavin, R.E. (1989). Cooperative learning and student achievement: Six theoretical perspectives. In C. Ames & M.L. Maehr (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Stacey, E. (1999). Collaborative learning in an online environment. Journal of Distance Education, 14(2), 14-33 [Onine]. Available: http://cade.icaap.org/vol14.2/stacey.html

Tuckman, B., & Jensen, M.A. (1977). Stages of small group development revisited. Group and Organization Studies, 2, 419-427.

Weinstein, C.E., & Meyer, D.K., (1991). Cognitive learning strategies and college teaching. In R.J. Menges & N.D. Svinicki (Eds.), In college teaching: From theory to practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in society. (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Yeoman, E. (1996). Sam’s café: A case study of computer conferencing as a medium for collective journal writing. Canadian Journal of Educational Communication, 24, 209-226.

1. The first author created this approach and was the course instructor.

2. The FirstClass interface allows for easy access to cross-group discussion because each group's icon is visible on a common desktop.

Christina De Simone is a researcher at the Centre for the Study of Learning and Performance at Concordia University in Montreal. She specializes in learning strategies and classroom research and teaches a distance education course in educational psychology with Richard Schmid.

Yiping Lou is an assistant professor in the Educational Technology Graduate Program, Department of Educational Leadership, Research, and Counseling at Louisiana State University. She specializes in instructional design, computer-supported collaborative learning, and research synthesis.

Richard Schmid is an associate professor and Chair of the Education Department at Concordia University in Montreal. He specializes in learning strategies as applied to the classroom and in the workplace. He co-teaches a distance education course in educational psychology with Christina De Simone.