VOL. 16, No. 1, 56-69

Effective help-seeking is an important strategy that is fundamental to successful learning whenever the student's knowledge or comprehension is insufficient to enable independent resolution of a problem. Nevertheless, it is often regarded with negative connotations. For distance education students, help-seeking takes place in a different context than for students in conventional education. This is characterized by limited face-to-face contact, little interaction between students, and often isolated learning. Consequently, if distance educators are to help students to make the most effective use of help-seeking strategies, it is first important to understand the nature of help-seeking among these students. This article describes a study that compared the help-seeking strategies used by students identified as high achievers in courses at the Open University of Hong Kong (OUHK) and groups identified as low achievers in an attempt to uncover any insights about successful help-seeking strategies that can be used by distance education students, specifically those in a predominantly Chinese culture. Data were collected by questionnaires completed by 712 students and telephone interviews with a subsample of 32. Although there were similarities between the two groups in help-seeking for academic difficulties, there was a tendency for more of the high-achieving students to seek help for personal difficulties relating to their courses. Several help-seeking strategies were identified.

Une demande d'aide efficace est une importante stratégie qui est fondamentale au succès de l'apprentissage quand les connaissances ou la compréhension de l'étudiant est insuffisante pour permettre de façon indépendante la résolution d'un problème. Néanmoins, cette action est souvent chargée de connotations négatives. Pour des étudiants d'éducation à distance, la demande d'aide prend place dans un contexte différent de celui des étudiants en éducation conventionnelle. L'éducation à distance est caractérisée par des contacts face-à-face limités, peu d'interactions entre les étudiants et souvent un apprentissage isolé. Conséquemment, si les éducateurs à distance doivent aider les étudiants à faire un usage des plus efficaces des stratégies de demande d'aide, il est d'abord important de comprendre la nature de ces demandes d'aide chez les étudiants. Cet article décrit une étude qui a comparé les stratégies de demande d'aide utilisées par des étudiants identifiés comme étant d'un niveau de performance élevé dans des cours à la Open University of Hong Kong (OUHK) avec des groupes, de cette même université, identifiés comme ayant un bas niveau de performance. Elle a pour but de découvrir les concepts sous-jacents des stratégies efficaces de demande d'aide connaissant du succès et pouvant être utilisées par les étudiants d'éducation à distance, plus particulièrement ceux faisant partie d'une culture chinoise prédominante. Les données ont été recueillies par l'entremise de questionnaires complétés par 712 étudiants et des entrevues téléphoniques avec un sous-échantillon de 32 personnes. Bien qu'il y avait des similarités entre les deux groupes dans leur demande d'aide pour répondre à des difficultés scolaires, la tendance était que plus d'étudiants de niveau de performance élevé avaient recours à la demande d'aide pour les difficultés personnelles relatives aux cours. Plusieurs stratégies de demande d'aide ont été identifiées.

Effective help-seeking is an important strategy that is fundamental to successful learning whenever the student’s knowledge or comprehension is insufficient to enable independent resolution of a problem (Karabenick & Knapp, 1991; Newman & Schwager, 1995; Ryan & Hicks, 1997). Not only is it a strategy that can help students to address their immediate learning needs (Ryan & Hicks), it can also be a way of improving their performance (Karabenick & Knapp). Research has indicated that certain types of students are able to appreciate the benefits of help-seeking as a strategy to promote their learning. Ryan and Hicks reported that students whose goals are to gain understanding, insight, and skill, and whose self-worth is measured by their mastery of these, are likely to view help-seeking as a positive strategy. They further reported that some groups of students might seek help for reasons other than to support their learning. For example, those whose goals are concerned with positive peer relationships might view help-seeking as an instrument to achieving this end.

The issue of gender differences in help-seeking has been considered by several writers, although no clear consensus has been reached. For example, Ryan and Hicks (1997) reported evidence to suggest that women are more likely than men to seek help, although other studies have reported no such gender differences (Newman, 1990, Ryan & Pintrich, 1997).

Nevertheless, help-seeking is often regarded with negative connotations. Karabenick and Knapp (1991) found that many students were able to report times when they could have used assistance with courses, but did not seek the help that probably would have enabled them to surmount their difficulties. Some students, particularly those who have a strong desire to be judged as successful and able, may construe help-seeking as admitting to lack of ability and thus consider it to be threatening to their self-worth and thus to be avoided (Ryan & Hicks, 1997). Ryan and Hicks found that those students who are particularly likely to feel threatened are those who “define success and self-worth as outperforming others but who perform lower than most other students” (p. 154). Consequently, they will often employ ineffective strategies such as giving up prematurely, waiting passively for somebody to offer an explanation, or persisting unsuccessfully on their own. It is therefore important for students to be aware of how help-seeking can be a positive learning strategy.

In order to encourage the development of effective help-seeking, it is important to understand the circumstances in which it can be perceived as threatening and those in which it can be perceived as valuable. For example, Daubman and Lehman (1993) found that students are more likely to seek help if their need for it can be attributed to external factors or lack of effort, rather than to, for example, lack of ability.

Considerable research has been done about the effectiveness of different types of help-seeking. Two particular types have been described: executive and instrumental (Karabenick & Knapp, 1991). Executive help-seeking, which places the responsibility on the helper, for example, by asking for the answer, reduces the time and effort required to complete a task. Instrumental help-seeking, which places the responsibility on the seeker, for example, by asking for a hint or an explanation of the principles leading to the problem’s solution, allows for greater independence in completing the task. Newman and Schwager (1995) further categorize these into requests for process-related information (hints or requests designed to figure out a rule or carry out an operation), explanations, clarification of information or answers, confirmation of uncertain answers, requests for the final confirmation of an answer or the correct answer, or requests for non-task-related information.

Even among those students who are prepared to seek help, their help-seeking may be counterproductive to their learning, for example, if they immediately ask for help before attempting or ask for an answer and then give up (Newman & Schwager, 1995). Consequently, as Newman and Schwager claim, it is important to encourage students to differentiate between help that will encourage their dependence on the helper and help that will facilitate mastery and long-term autonomy.

For distance education students, help-seeking takes place in a different context than for students in conventional education. This is characterized by limited face-to-face contact, little interaction between students, and often isolated learning. Consequently, if distance educators are to help students to make the most effective use of help-seeking strategies, it is first important to understand the nature of help-seeking among these students. This article describes a study that compared the help-seeking strategies used by students identified as high achievers in courses at the Open University of Hong Kong (OUHK) and groups identified as low achievers in an attempt to uncover any insights about successful help-seeking strategies that can be used by distance education students, specifically those in the predominantly Chinese culture of Hong Kong.

The study sought to investigate whether either the high-achieving or low-achieving group of students is more likely than the other to seek help, the kinds of problems for which they seek it, and from whom they seek it. A further question was whether either group was more likely than the other to engage in instrumental or executive help-seeking. For both groups of students, specific research questions with respect to high- and low-achieving students were:

These questions were also considered with respect to the independent variable gender. This was considered because gender, along with educational background and previous distance education experience, has been identified as a major factor affecting students’ performance (Fan & Chan, 1997) and is one of the major independent variables considered in the overall project (see Centre for Research in Distance and Adult Learning, 1999, for discussions of the other two).

Data were collected by questionnaires completed by 712 students and telephone interviews with a subsample of 32. Of the 712 students, 343 were male and 369 female. The high-achieving group contained 197 men and 263 women (total = 1,460), and 146 men and 106 women (total = 252) were low achievers.

The sample was selected from students ranked in the top 5% (high achievers) and bottom 5% (low achievers) of OUHK courses over four semesters from August 1996 to February 1998. The data reported in this article were collected as part of a larger study of the study habits and preferences of high-achieving and low-achieving distance education students at OUHK. Full details about the methodology, questionnaire, and interview schedule have been reported by Chan, Jegede, Fan, Taplin, and Yum (1999). This article focuses on describing the items that were designed to investigate students’ help-seeking behaviors.

It was considered important to investigate the students’ help-seeking behaviors in relation to the full spectrum of their student lives. Consequently, the items constructed for this part of the questionnaire were based on the work of Grayson, Clarke, and Miller (1995), who included financial, course-related, domestic, interpersonal and personal crises, and managing resources and facilities.

One series of questionnaire items was designed to investigate patterns in the formation of study groups with other students. Using a five-point scale, students were asked to indicate whether they preferred to study individually or with other students, whether they had ever formed or joined an informal study group, how many people were in the group, and whether the group communicated by e-mail, telephone, fax, or in face-to-face meetings.

The statement “I believe that help-seeking is a good way to learn and grow” was used as an indicator of the extent to which the students regarded help-seeking as a useful strategy. This item was rated on a 5-point scale, where 5 represented strongly agree and 1 represented strongly disagree. A further set of questions also requiring the students to give the same ratings sought to gain some information about the kind of help they preferred to seek, whether it was to have the person demonstrate the procedure, or to tell the answer, or to give just enough information that the person could then do it alone.

The other questionnaire item related to help-seeking was designed to explore what the students sought help about and from whom they sought it. They were given a list of problems or difficulties that included new study materials; volume of materials to study; integration of studying and other duties; writing skills (in the language used in the course); self-motivation; anxiety about tests and examinations; finding time to study; and conflicts about spending time with family, friends, or colleagues. For each of these areas they were asked to indicate whether they sought help or not, and if so whether it was from the course coordinator, tutor, a work colleague, another student in the course, a friend or family member, or somebody who had completed the course.

The interview questions were designed to draw out more information about why students sought help and particularly the nature of the help they sought.

The mean ratings on the item regarding help-seeking as a valuable way to learn were 3.73 for 454 high achievers and 3.64 for 250 low achievers. There were no significant differences in the means of the high and low achievers, with both groups rating it between 3 (occasionally) and 4 (often) as a good way to learn.

In the interview the most common opinion was that help-seeking is a good way to learn only if it comes after having attempted the task to the best of one’s ability (6 high achievers and 8 low achievers). One high achiever and two low achievers said they had tried asking for help but had given up: the former because he was embarrassed that he still did not understand, and the latter because the helper was too busy. Another high achiever said it is important that the helper does not look down on the help seeker, because this can have an adverse psychological effect. Four high achievers and two low achievers said they would have liked to ask for help but did not because it was “too troublesome” to make contact with the tutor or find somebody else with the necessary knowledge or expertise.

A two-way analysis of variance indicated that there were no significant differences between the mean ratings of gender and achievement groups regarding help-seeking as a good way to learn (mean square .755; F ratio .778).

One of the criteria included to measure students’ help-seeking habits was whether they formed voluntary study groups other than in formal tutorials

Fifty-nine high achievers and 29 low achievers formed or joined study groups. In both the high achievers’ and the low achievers’ groups most of the students said that they worked alone rather than forming groups. In the follow-up interview the reasons given equally by both groups for this included that they could not make time to work with a group (7 high achievers and 7 low achievers) and that they were afraid they would get distracted and chat instead of working (1 high achiever and 2 low achievers). Six of the high achievers also expressed concern that if they worked in a group they might have to slow their pace to that of the slowest member, although no low achievers gave this as a reason. Five high achievers and two low achievers said they did not need to study in a group. Five high achievers and 10 low achievers said they would have preferred to study in a group if it had been easier to organize. The seven high achievers and three low achievers who said working in a group had helped them attributed this to being able to pool ideas and divide tasks. Where groups were formed the most common size was three to five students.

For the mode of communication used by groups students were permitted to check as many boxes as were appropriate. In both high-achieving and low-achieving categories the most common mode of communication was face-to-face, followed closely by telephone. Little use was made of e-mail, although 85% of OUHK students claim to have Internet access.

Of the 88 students who identified use of study groups, 42 of the 59 high achievers were female, and 18 of the 29 low achievers were male. There was a significant relationship between gender and achievement in the formation of self-study groups (<F128M>c<F255M^>2=9.28, p<<0.01), with the largest proportion being the high-achieving women (16%) and the smallest the low-achieving women and high-achieving men (both 9%).

For the mode of communication by study groups, 81% of the high-achieving women who joined groups met face to face, as did 80% of the low-achieving women, compared with 78% for both the high-achieving and low-achieving male groups.

Fan, Taplin, Chan, Yum, and Jegede (1999) reported elsewhere that the students indicated that the problems most likely to have caused difficulties with their work were finding time to study, integrating study with their other commitments, the volume of course materials, and test and examination anxiety. When the numbers of students in the high-achievers and low-achievers groups who said they sought help for these and other problems are compared, chi-square tests suggest that there were no statistically significant relationships between help-seeking and achievement. In both high-achieving and low-achieving groups the largest numbers of students said they had sought help for problems related to new study materials (77% and 73% respectively), followed by test and examination anxiety (54% and 50%). Similar numbers said that they sought help for problems relating to volume of materials (46% and 48%) and integration of their studies with their other duties and responsibilities (46% and 48%). In the high achievers’ group the next three were spending time with family, friends and colleagues (43%), writing skills (42%), and self-motivation (38%), whereas the order for the low achievers was writing skills (42%), then self-motivation (37%). Finding time to study was the problem about which the least number of students in either group sought help (30% and 26%).

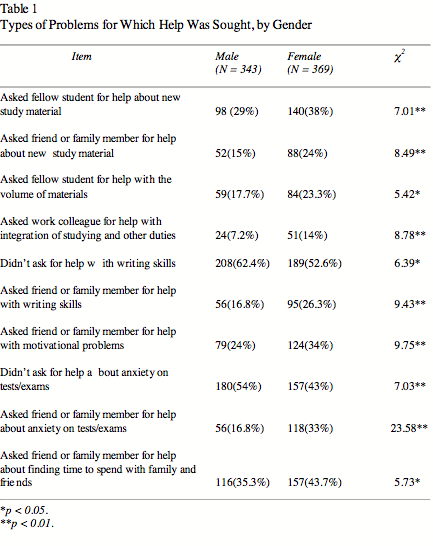

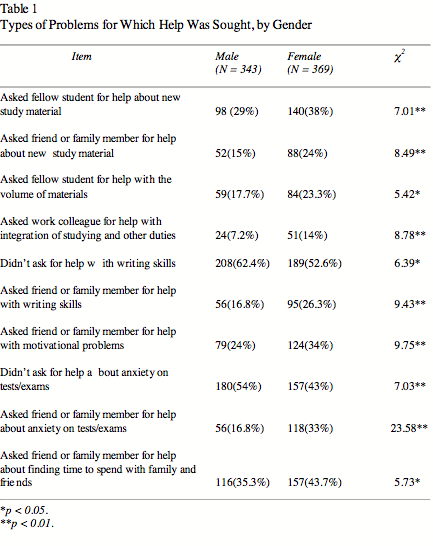

Table 1 shows the numbers of students in each group who said they had sought help for the given problems.

Because there were no significant differences in achievement, a comparison was made between genders without considering gender by achievement. There were 10 items on which chi-square tests indicated statistically significant differences. These results show a clear tendency for more women than men to seek help for various problems, asking: fellow students, friends or family members for help with new study material; fellow students for help with the volume of materials; work colleagues for help with integration of studying and other duties; and friends or family members for help with writing skills, motivational problems, test or examination anxiety, and finding time to spend with family and friends. On the other hand, more men said that they did not seek any help at all for difficulties such as writing skills and test or examination anxiety.

The high-achieving women had the highest percentages who said they sought help with new study materials (78%), writing skills (46%, the same as low-achieving women), self-motivation (57%), test and examination anxiety (57%), finding time to study (32%), and finding time for family and friends (46%). The low-achieving women were the next most represented group on all of these except for two problems on which there were slightly more low-achieving men The low-achieving women had the highest representations in seeking help for volume of work (50%) and integration of duties (51%), with the high-achieving women the second highest (48% on both problems). The differences between these two groups were the largest on test and examination anxiety (57% of high-achieving women and 48% of low-achieving women), self-motivation (42% and 34% respectively), and finding time to study (32% and 22%). The high-achieving male group had the fewest students seeking help for volume of materials (43%, the same as the low-achieving men), integration of duties (40%), writing skills (36%), self-motivation (27%), and anxiety about tests and examinations (43%). The four problems on which the highest proportions of students sought help were the same for all categories: new study materials, volume of work, test and examination anxiety, and integration of duties. Finding time to study was commonly the problem for which the fewest in each category sought help

There were no significant differences between the mean ratings of high and low achievers of their preference for seeking help through asking for the answer, for enough help to solve the problem alone, or for a demonstration to copy. Similarly, there were no significant gender differences. The highest mean rating was given to “asking for just enough help to be able to solve the problem alone.” This is a type of instrumental, process-related help-seeking that places at least some of the responsibility on the seeker. The other two options, both of which are executive help-seeking that places the responsibility on the helper, were rated as being used less frequently.

In the interview the 35 students were asked to give specific examples of the kind of help they sought. Only four students (2 high achievers and 2 low achievers) gave examples of instrumental help-seeking, for example, to check whether what they had done was correct. Sixteen examples (6 from high achievers and 10 from low achievers) were given of executive help-seeking, for example, “guidelines about what to do” or “explanation of what the questions were asking.” Four high achievers and six low achievers said the help they received was usually useful. Six high achievers and four low achievers said it was not, mainly because their helpers (usually tutors) were too busy and in some cases too impatient or not well enough informed to give the detail they needed. One high achiever mentioned that she had sought help in the form of asking others to take over some of her other tasks to allow her to cope better with her studying.

Graphs were used to compare the sources from which help was sought by high and low achievers for the eight types of problems. It can be seen that the patterns are similar for the two groups. For course-related problems that required specialized help such as new study materials and volume of materials, the majority in both groups asked their tutors for help, followed by other students and then former students of the course. It can be noted that slightly more low achievers sought help from former students. For problems with writing skills required to do the coursework, however, the majority in both groups asked friends or family for assistance, with slightly more high achievers than low achievers seeking help from this source.

For organizational problems such as integration of studying with other duties and responsibilities and finding time to study, the majority in both high-achieving and low-achieving groups sought help from family or friends. For problems with integration of duties the tutors were the next most sought-after helpers, although they did not feature prominently with either group for help with finding time to study. Other students and colleagues were also approached for help with organizational problems.

For personal problems, including self-motivation, test and examination anxiety, and finding time to spend with family, friends, and colleagues, friends and family and fellow students were clearly the most frequently approached for help. University personnel such as tutors played a much less significant role in this kind of problem—although the tutors were approached by 17-18% of help-seekers for problems relating to test and examination anxiety.

The question of preferred sources of help was followed up in the interview, but there were no consistent patterns in the responses. One high achiever and five low achievers said that they would prefer to ask the tutor for help, but that the tutors were usually so busy and so much in demand that it was not easy to receive the quality and quantity of help that they required.

When the graphs were broken down by gender, some further patterns emerged. The highest percentages of the high-achieving female group sought help from family or friends for all problems except new course materials, for which the majority asked the tutor. Next, they tended to ask fellow students, except for help with writing skills (tutor) and integrating duties (similar percentages asked fellow students and tutor). The largest proportions of the low-achieving women also sought help from family or friends except for new course materials and writing skills (tutor). Again, the second largest percentage asked fellow students.

The largest percentage of the high-achieving men asked the tutor for help with new course materials, volume of materials, and writing skills; family or friends for help with self-motivation and finding time to spend with others; and other students about test and examination anxiety. Equal numbers asked tutors and family or friends for help with integrating duties. The largest numbers of low-achieving men asked the tutor for help with new course materials, volume of materials, integration of duties (with the same number asking a friend), and writing skills; family or friends about motivation; and fellow students about test and examination anxiety.

In all cases the high-achieving female group had the highest percentage of students asking family or friends, followed in most cases by the low-achieving women. Also, for all problems higher percentages of high-achieving women than other groups sought help from fellow students. For seeking help from other sources there were no clear patterns, and the

The purpose of this article is to report aspects of the help-seeking behaviors of high-achieving and low-achieving students at OUHK. There was no evidence of statistically significant differences between high and low achievers, but some interesting patterns have suggested some implications for further research or policy implementation. Most of the students regarded help-seeking as a good way to learn. Interviews suggested, however, that they thought they should try to do it themselves first. The main reasons for not seeking help, apart from not needing it, were that access to a tutor or suitable knowledgeable person was difficult. One implication suggested by these outcomes is the need to explore strategies that will make it less troublesome for students to seek help when they need it.

Most of the students indicated that they did not seek help for any problems other than those associated directly with their study materials. Although there were similarities between the two achievement groups in help-seeking for academic difficulties, there was a tendency for more of the high-achieving students to seek help for personal difficulties related to their courses. There was a tendency for more women to seek help, particularly from family or friends, for a range of problems, and usually for more of the high-achieving women to do so than the low-achieving women. The biggest differences between the numbers of high-achieving and low-achieving women seeking help were for test and examination anxiety, self-motivation, and finding time to study. The question of whether seeking help for these problems has given the high-achieving women the edge over the low achievers warrants further investigation. Where similar numbers of high- and low-achieving women sought help for the other problems, there is the implication that the former may be doing something different that enables them either to receive more effective help or to use it more effectively. The data about preferred kinds of help sought do not give any support to this conjecture, but this is also worthy of further investigation. Another interesting observation is that for most of the problems considered in this study, the group in which the fewest students sought help was the high-achieving men. This suggests that they either did not need help or found other methods of solving their problems that were clearly not detrimental to their achievement.

Except for problems directly related to coursework, on which most sought help from tutors, the majority of students asked family or friends for help, with fellow students being another popular source. It is interesting to speculate whether the high achievers are in fact receiving help from family or friends who have better knowledge or expertise and are therefore able to help them more effectively than the family or friends helping the low achievers. Further investigation of this question could reveal some useful insights about the quality of help received by high and low achievers.

A number of help-seeking strategies were identified that included the establishment of self-formed study groups. Although the questionnaire data revealed that the majority of students in both the high-achieving and low-achieving groups reported that they preferred to work alone, the follow-up interviews indicated that a number of students, particularly low achievers, would like to work with groups if it were easier to organize. This organization could be facilitated through the use of e-mail. As noted, few of the respondents reported the use of e-mail to discuss problems with fellow students, for two possible reasons. One is that although 85% of OUHK students report having access to the Internet, probably many of these do not actually have regular access to using it for study purposes. The second reason is that students may be inhibited from using e-mail for lengthy discussions because of the time involved in writing messages, particularly when this is in their second language. Therefore, it may be worthwhile to explore further how the use of this medium can be enhanced. A significant relationship was found in the questionnaire analysis between gender and achievement in the formation of self-study groups, with the largest proportion being the high-achieving women and the smallest the low-achieving women. This suggests that it may be worthwhile to conduct further research to investigate the potential impact of participating in study groups on achievement, particularly of low-achieving female students

In both groups the students reported a preference for receiving a type of instrumental help where the helper provided enough of a hint for the student to solve the problem, although most of the examples given in the interviews were in fact executive help-seeking where the helper tells the answer or demonstrates. The interviews indicated that the help given was sometimes useful and sometimes not, and one of the main reasons given was that the helper was unable to provide adequate assistance that took into account the learner’s level of understanding and needs. This suggests that some tutor training in appropriate help-giving might enhance the quality of students’ learning.

Although this project did not reveal many statistically significant differences between the help-seeking behaviors of high- and low-achieving OUHK students, it is anticipated that further investigation of the issues outlined above will help to enhance the quality of the distance education experience for both high- and low-achieving students.

This project on which this article is based was funded by the President’s Advisory Committee on Research and Development, the Open University of Hong Kong.

Chan, M.S.C., Jegede. O., Fan, R., Taplin, M., & Yum, J.C.K. (1999, October). A comparison of the study habits and preferences of high achieving and low achieving Open University students. Paper presented to the 13th annual conference of the Asian Association of Open Universities, Beijing.

Centre for Research in Distance and Adult Learning. (1999). Factors that enhance high achievers’ success in Open University. Unpublished project report. Open University of Hong Kong.

Daubman, K., & Lehman, T. (1993). The effects of receiving help: Gender differences in motivation and performance. Sex Roles, 28(11/12), 693-707.

Fan. R.Y.K., & Chan, M.S.C. (1997, November). A study on the dropout in mathematics foundation courses. Paper presented to the 11th annual conference of the Asian Association of Open Universities, Malaysia.

Fan, R., Taplin, M., Chan, M.S.C., Yum, J.C.K., & Jegede, O (1999, October). Effective support services—A target-oriented approach. Paper presented to the 13th annual conference of the Asian Association of Open Universities, Beijing.

Grayson, A., Clarke, D., & Miller, H. (1995). Students’ everyday problems: A systematic qualitative analysis. Counselling, August, 197-202.

Karabenick, S., & Knapp, J. (1991). Relationship of academic help seeking to the use of learning strategies and other instrumental achievement behavior in college students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83, 221-230.

Newman, R. (1990). Children’s help-seeking in the classroom: The role of motivational factors and attitudes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 71-80.

Newman, R., & Schwager, M. (1995). Students’ help-seeking during problem solving: Effects of grade, goal and prior achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 32, 352-376.

Ryan, A., & Hicks, L. (1997). Social goals, academic goals, and avoiding seeking help in the classroom. Journal of Early Adolescence, 17(2), 152-181.

Ryan, A., & Pintrich, P. (1997). “Should I ask for help?” The role of motivation and attitudes in adolescents’ help-seeking in math class. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 1-13.

Margaret Taplin is a research fellow in the Centre for Research in Distance & Adult Learning at the Open University of Hong Kong.

Jessie Yum is a research coordinator in the Centre for Research in Distance & Adult Learning at the Open University of Hong Kong.

Olugbemiro Jegede is the Director of the Centre for Research in Distance & Adult Learning at the Open University of Hong Kong.

Rocky Y.K. Fan is an associate professor of mathematics in the School of Science and Technology at the Open University of Hong Kong.

May S.C. Chan is an assistant professor of mathematics in the School of Science and Technology at the Open University of Hong Kong.