VOL. 16, No. 1, 102-112

The educational attainment levels of First Nations people in Canada lags behind that of mainstream society. Because many reserves are in rural or remote areas, attending postsecondary institutions has meant leaving the community. However, advances in information technologies and distance education program delivery mean that First Nations people can obtain postsecondary educational credentials without having to leave their home communities. This would be both convenient and less disruptive for the student. However, before programs can be delivered, the current technological competence and usage levels in reserves must be determined. The primary thrust of this research provides baseline information on the access to and use of various technologies and the degree, type, pervasiveness, and availability of technologies such as computers, Internet, e-mail, voice mail, computer networking, satellite systems, teleconferencing, and other communications services. This investigation of information technology usage in selected First Nations communities provides insight into their readiness for distance learning opportunities in the community.

Les niveaux de réalisation éducationnelle des personnes faisant partie des Premières Nations du Canada affichent du retard par rapport aux niveaux éducatifs de la société dominante. Étant donné que plusieurs des réserves se situent dans des régions rurales ou éloignées, fréquenter des institutions postsecondaires a voulu dire pour ces personnes quitter la communauté. Cependant, les progrès des technologies de l'information et l'offre de programmes d'éducation à distance signifient que les personnes des Premières Nations peuvent obtenir des certifications postsecondaires sans devoir quitter leur communauté natale. Cela serait à la fois pratique et moins perturbateur pour l'étudiant. Cependant, avant que les programmes ne puissent être offerts, les niveaux de compétence technologique et d'usage qui existent actuellement dans les réserves doivent être évalués. Le premier aspect de cette étude fournit de l'information de base sur l'accès et l'utilisation des technologies telles que les ordinateurs, l'Internet, le courrier électronique, la messagerie vocale, les réseaux informatiques, les systèmes satellites, la téléconférence et d'autres services de communication. Cette recherche sur les utilisations des technologies de l'information dans des communautés choisies appartenant aux Premières Nations donne un aperçu à savoir si oui ou non, ces communautés sont prêtes à saisir les occasions d'éducation à distance.

We are living in an information explosion. Technological advances such as bigger and faster computers, e-mail, electronic bulletin boards, the Internet, voice mail, and facsimile machines have changed the world we live in. They have also changed the way we do business, how we gather information, and how we communicate with each other. Indigenous people in Canada recognize their need to gain access to and develop competence in new digital telecommunications.

First Nations people are also embracing technology. Cellular telephones are a staple at meetings, and band administrators rely heavily on fax machines to transfer documents to government agencies and to other First Nations. A recent First Nations Trade Fair, held in conjunction with the joint Assembly of First Nations and the Congress of American Indians Annual General Assemblies, highlighted extensive information services such as specialized computer programming designed to accommodate specific First Nations needs (band membership or community demographics); interactive CD ROMs that assist language instruction; numerous Indigenous subject-related Web sites; and e-commerce.

Youth are becoming more familiar with communications technologies. Many First Nations schools are participating in the Schoolnet program that links them to the Internet. Students are taught computer skills as part of their curriculum, and computer labs are being set up in schools.

Indigenous peoples of Canada are increasingly pursuing education and credentialism. For example, First Nations’ enrollment in postsecondary institutions has increased to more than 27,000 according to the Department of Indian Affairs’ Basic Departmental Data, 1997 (Government of Canada, 1997). However, the educational attainment level of Aboriginal people in Canada falls below that of the general Canadian population. This document shows postsecondary enrollment rates for First Nations people between the ages of 17-34 years at 6.0% compared with 10.4% in Canadian society in 1996. This causes grave concern to First Nations leaders who wish their people to be more integrated into the mainstream economy. Education is seen as a means of achieving this goal.

Can First Nations peoples’ acceptance of information technologies be used to increase education levels and educational attainment in the community? Athabasca University, in an effort to fulfill its mandate to increase access to university-level studies to all adult Canadians commissioned a study to determine core technological competences1 in the First Nations setting.2

The following are results from the Athabasca University Technology Usage Project. Data were collected by self-administered questionnaires and face-to-face or telephone interviews using a variety of open-ended and closed-ended questions. Through a combination of subjective and objective data I explored the current levels of technology use and availability in the communities. I reasoned that acceptance and familiarity with information technologies, coupled with the need and desire for postsecondary instruction, could pave the way for distance learning programming in that First Nations community.

I conducted 10 interviews at each of six sites for a total of 60 interviews. Interviews conducted with various reserve-based agency employees attempted to capture their experiences and insights into community technology use. Research participants were individuals working in band administration offices, schools, and agencies. They were viewed as key informants and were chosen because they used various types of technology while performing their work duties, were community members, and as community members had knowledge of technology use and availability in their community.

Self-administered questionnaires and face-to-face or telephone interviews gathered information in seven areas: educational attainment, employment, or training; individual use of technology; frequency of individual technology use; comfort level of individual technology use; availability of individual technology use; community availability; and community use. Participants were asked two types of questions. First, they were asked about their individual technology use while performing duties and, second, their opinion of use and availability of technology in the community.

Distance learning is a viable alternative for those living in sparsely populated regions or for those with domestic responsibilities that make leaving home to attend school a daunting if not impossible task. First Nations people, especially those living on reserves fit both these criteria. They reside primarily in the sparsely populated north and in the west according to Statistics Canada (1998), “in 1996, the highest concentration of Aboriginal people in Canada were in the north and on the prairies. More than four out of every five Aboriginal people lived west of Quebec” (pp. 3-4). In addition, the same report cites the high number of female-headed lone-parent families within the Aboriginal community. Home study and distance learning allow geographically isolated individuals to obtain educational credentials.

Distance learning can serve the needs of the institution, the community, and the student. Monaghan (1991), in his article “Ambitious Program Run by U.S. College Offers Hope to Canadian Indians,” described a distance learning program run by Gonzaga University at Canim Lake in British Columbia. Students who were forced to leave the community to attend postsecondary institutions often dropped out before completion for many reasons including loneliness, intimidation, and an alien, competitive environment. Gonzaga’s program linked students to campus by computer during the school year. Students would then bring their families with them while they attended summer session courses on campus.

Sharpe (1990) detailed the logistics of an Indigenous teacher program delivered in Labrador by Memorial University of Newfoundland. Students obtained either a two-year teaching certificate or a five-year baccalaureate degree in their home community. He stated that the program was constantly under revision to find the best way to deliver it. The logistics of program delivery included the courses required, instructor availability, instructor sensitivity to Native communities, scheduling, student teaching, responsibilities at home, resources, mode of delivery, curriculum content, and living accommodation. Program success depends entirely on resourcefulness and innovation.

Keast (1995) discussed a pilot project from the University of Alberta to remote communities where approximately 70% of the students enrolled were Aboriginal. Such courses were delivered via multipoint videoconferencing to a maximum of six sites. These programs are not without growing pains, with the students’ program evaluations citing concerns with program planning and administration. Students also expressed an interest in having more course offerings, more effective program advising, and career counseling. Despite complications, the project was deemed a “moderate success” with a 51% completion rate (p. 41).

Fiddler (1992) detailed the operations of the Wahsa Distance Education Centre for Aboriginal secondary and postsecondary students in northwestern Ontario. The program operates in 23 remote communities associated with the Northern Nishnawbe Education Council (NNEC). This distance learning program, which allows students to remain in their communities, has been funded by Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) since 1990. Radio broadcasts are used to deliver programming to community learning centers. Correspondence courses are also delivered with the assistance of coordinators and tutors. Effective program delivery methods, suggestions for program improvement, and expansion are offered.

Spronk and Radtke (1988) examined the issues faced by Aboriginal women who attempt distance education. They cite Aboriginal women as 80% of the enrollees in distance programs available to Aboriginal people through Athabasca University. They state that distance learning is attractive to Aboriginal women because it is self-paced and allows them to fulfill domestic responsibilities. Distance learning also eliminates transport and child care problems for these women. Various program delivery modes and student services are discussed, and their effectiveness is rated.

Owen and Hotchkiss (1991) examined Athabasca University graduates from 1985-1990 to determine whether the university was fulfilling its mandate to students. They found that 65% of students were female, primarily living in urban rather than rural areas, and “the removal of time and distance, through a flexible study structure, was an attraction to all Athabasca University graduates” (p. 10). The authors concluded that Athabasca University was successful in removing some of the barriers that prevent individuals from obtaining postsecondary education. However, the growth of new technologies raises questions about the level of access, comfort, and experience with technologies in First Nations communities.

Spronk (1995) outlined the historical, economic, cultural, and political situation of First Nations people in Canada. Using this information as a backdrop she then detailed a variety of collaborative distance education and Native studies programs being delivered across the country. She credits these programs with increasing the participation of Aboriginal students in postsecondary institutions through improved accessibility. Spronk surveys the program mandates and explores the challenges experienced with program delivery such as curriculum and course content, instruction and delivery, and political constraints.

The data were collected from participants of a Technology Usage Project conducted with First Nations communities affiliated with a tribal council and its administrative offices in summer 1998.

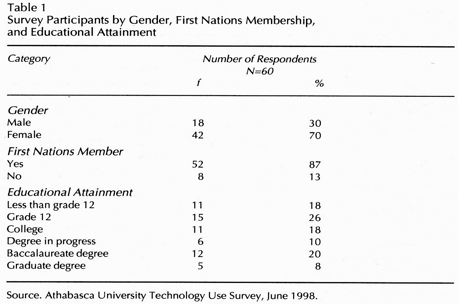

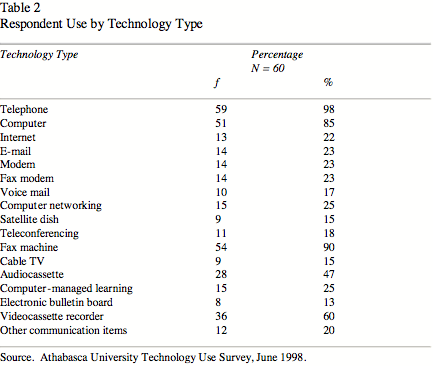

The 60 respondents who came from the six communities varied in education, employment, and training; were in different phases of their careers; and ranged in age from the early 20s to the late 50s. Identification data, summarized in Table 1, showed that most respondents (87%) were First Nations and 75% were reserve residents. The vast majority of those who were First Nations members were from tribal council member bands.

Respondents were employed and worked in various jobs in the community, but mostly in clerical positions. Most (80%) were employed in full-time, permanent positions; 10% worked part time; and 10% were employed temporarily.

There was an overrepresentation of women, with 70% women and 30% men. From my experience with First Nations communities, this sample is consistent with the gender ratios of most First Nations administration, school, and service agency work forces. Generally more women than men are employed in band administration.3

Respondents’ educational attainment levels ranged from less than grade 9 completion to postgraduate university degrees. Slightly fewer than 60%, or 34 of 60 respondents, had some form of postsecondary education. The educational attainment breakdown for respondents with postsecondary education is as follows: 11 (18%) have college training; six (10%) have a university degree in progress; 12 (20%) have baccalaureate degrees; and five (8%) have graduate degrees.

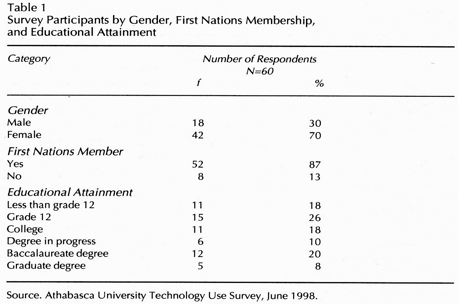

Respondents were asked about their regular personal use of technology in the workplace including telephone, computer, Internet, e-mail, voice mail, computer networking, satellite dish, teleconferencing, fax machine, modem, fax modem, cable television, audiocassette, computer managed learning, electronic bulletin board, videocassette recorder (VCR), or other technologies.

Table 2 summarizes the use of each technology. Some technologies are universally used in the respondents’ workplace: telephones were used by 98% and fax machine by 90%; computers had replaced typewriters, with 85% use. Less frequently used technologies were the audiocassette (47%) and the VCR (60%). However, most computer-based communications technologies listed on the questionnaire were used by only a quarter of respondents; computer-managed learning (25%); the Internet (22%); e-mail (23%); modem (23%); fax modem (23%); computer networking (25%); voice mail was used by only by 17%; an electronic bulletin board by 13%. Audioconferencing (18%); satellite dishes (15%); and cable TV (15%) were also used by only a few participants, but cellular phones were used by 20%.

This means that 70% of the listed technologies were used by a maximum of 25% of the respondents. However, all technologies were used by some individuals in the communities as the data show that no technology listed in the question was unused. Although not all respondents found these technologies essential to the completion of their daily duties, many stated that using some of these technologies would make their daily tasks easier.

Technology use at the six sites varied greatly. For example, individuals at Site 2 used 53% of the listed technologies on a daily basis, whereas those at Site 4 used 94%. The variance might be explained by the types of work performed by the individual respondents, and some were more technologically advanced than others. One individual used the Internet, fax modem, modem, electronic bulletin board, and computer networking several times a day, whereas others used only the telephone, computer, and fax machine.

Respondents were then asked which technologies they used the most while performing their work duties. A majority of the listed technologies, 13 of 17 or 76%, were used daily by the respondents. The telephone, computer, and fax machine were reported as the most frequently used technologies. All respondents used them. These were closely followed by the video tape-recorder and audiocassette, which were used by seven and nine respondents respectively.

Other technologies (Internet, e-mail, modem, fax modem, voice mail, computer networking, satellite dish, cable TV, computer-managed learning, and electronic bulletin boards) were used much less frequently. Respondents were asked why they did not use certain technologies. They answered that they were not readily available for their use; that they were too busy to learn how to use them; or that they were comfortable with the limited technology they had. When they were questioned about their comfort levels with using various technologies, the most comfort was reported with the technologies they used most frequently. The telephone, computer, and fax machine had the highest comfort levels for the respondents. However, most were not keen on learning newer software. Many commented that they would like Internet training. Technologies that were never used were electronic bulletin board (in 5 sites), voice mail (in 2 sites), computer networking (seldom used or never used in 3 sites), Internet (1 site), cable TV (in 2 sites), and satellite dishes (never used in 1 site and seldom used in 3 others).

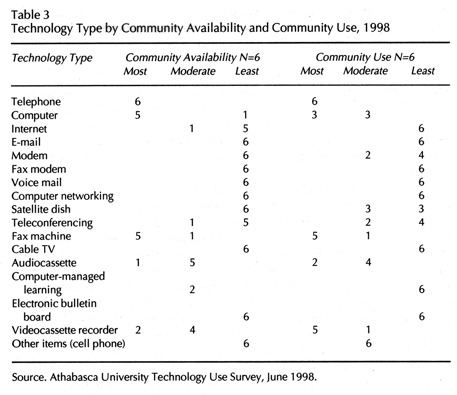

As community members, the respondents’ opinion on technology use and availability in the community was solicited. When six to 10 members at a site responded positively, the technology was considered most available; 2-5 positive responses were labeled moderately available; and least available was one positive response. Table 3 shows the respondents’ opinion on the availability of technologies and the use of technology in the community.

When asked about the availability of technology in the community, all groups stated that the telephone was most available, followed by the computer and fax machine. The VCR was reported as most available in two groups and audiocassette was deemed most available by one. Moderate availability technologies most frequently included audiocassettes and VCRs. Cellular telephones were also said to be moderately available by all groups. Least available technologies included e-mail, modem, fax modem, voice mail, computer networking, electronic bulletin boards, and the Internet.

Respondents were then asked about the use of technology in the community; Table 3 shows these findings. All groups stated that the telephone was most used. This was followed by the computer and VCR. The computer and fax machine were reported as readily available and frequently used by almost all the groups. Moderate technology availability and use was recorded for audiocassettes and VCRs. Audiocassettes were moderately used in four of six groups.

The least used technologies in the communities were the Internet, e-mail, modem, fax modem, voice mail, computer networking, cable TV, satellite dishes, and the electronic bulletin board.

Respondents stated that use and availability were closely linked. If a service or technology was available in the community, in their opinion it would be used. For example, they said that if the Internet were more readily available to community members, it would be more widely used. Some suggested that school computers could be made available to community members.

Internet access was viewed as important to respondents. Many feel that valuable and recent information available on the Internet could help them in their jobs. E-mail and voice mail were viewed as time-saving devices that would allow them to leave a message for co-workers and return to their duties. However, this convenience is not available to them in their workplace. Some said they must sometimes make several attempts to reach co-workers for information. This is costly, time-consuming, and frustrating.

The telephone, computer, and fax machine were used regularly by almost all respondents, whereas the Internet, e-mail, computer networking, and modem were used by fewer than one quarter (of respondents). Other technologies such as the electronic bulletin board and the satellite dish were used by fewer than 10 individuals.

Respondents were keen to learn more about the Internet and to upgrade their computer skills. They felt that although many of the new technological advances were making their way to their workplaces or to the reserve, they were being left behind technologically. They believed that if they had more skills they could provide mentorship and support for new learners.

Most technologies were available almost exclusively in the administration offices, service agencies, and schools. Respondents believed that all community members should be computer literate and have access to communications systems, but there was a feeling that if the community members were not “brought up to speed” with regard to technology, they would have a much harder time finding employment in a society that increasingly relies on technology. Greater access to the Internet is essential if students are to have the potential to participate in distance learning opportunities.

The availability of technologies and the willingness of the potential students to gain academic credentials make the reserve setting a perfect location for distance learning program delivery. Delivering distance learning programs makes sense. Many obstacles such as loneliness, lack of a familial support network, housing, child care, and transport that are faced by students who leave their home communities to obtain academic training can be alleviated when students can remain in the community. First Nations people are aware of the increasing need for academic credentials to compete in today’s economy. Distance learning is the answer for people who are ready, willing and able to gain academic qualifications, but having an appropriate experienced student support network in place is essential.

Government of Alberta. (1998). First Nations of Alberta: Indian register population, December 1997. Edmonton, AB: Intergovernmental and Aboriginal Affairs.

Government of Canada. (1997). Basic departmental data, 1997. Ottawa: Ministry of Public Works and Government Services.

Fiddler, M. (1992). Developing and implementing a distance education secondary school program for isolated First Nation communities in Northwestern Ontario. (ERIC Microfiche Accession No. ED 400 156).

Keast, D. (1995). Access to university studies: Implementing and evaluating multi-point videoconferencing. Canadian Journal of Continuing University Education, 23(1), 29-47.

Monaghan, P. (1991). Ambitious program run by U.S. college offers hope to Canada’s Indians. Chronicle of Higher Education, May 15, p. A3.

Owen, M., & Hotchkiss, R. (1991). Who benefits from distance education? A study of Athabasca University graduates, 1985-1990. Research/Technical Reports 143. (ERIC Accession No. ED 34-301).

Sharpe, D.B. (1990). Successfully implementing a Native teacher program through distance education in Labrador. In D. Wall & M. Owen (Eds.), Distance education and sustainable community development. Edmonton, AB: Canadian Circumpolar Institute with Athabasca University Press.

Spronk, B. (1995). Appropriating learning technologies: Aboriginal learners, needs, and practices. Why the information highway? In J. Roberts & E. Keough (Eds.), Lessons from open and distance learning (pp. 77-101). Toronto, ON: Trifolium Books.

Spronk, B., & Radtke, D. (1988). Problems and possibilities: Canadian Native women in distance education. In K. Faith (Ed.), Toward new horizons for women in distance education: International perspectives (pp. 214-228). London: Routledge.

Statistics Canada. (1998). The Daily, January 13, 1998, pp.

1. Core technological competences are defined as access, comfort, and experience using a variety of communications technologies.

2. The First Nations communities participating with this study included member bands associated with a central Alberta tribal council and its administration offices. The bands have a total population of 6,000 with 1,600 living off-reserve (Government of Alberta, 1998).

3. I have worked extensively with First Nations communities for the past 12 years.

Cora Voyageur teaches in the Sociology Department at the University of Calgary. She completed her doctorate at the University of Alberta where the sociology of work and Native employment was one of her areas of specialization. Her academic research focuses primarily on the Aboriginal experience in Canada, which includes women’s issues, justice, employment, education, and economic development. She has worked with many First Nations communities and organizations to conduct community-initiated research in the Aboriginal community. She is a member of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation from Fort Chipewyan, Alberta.