SPECIAL FEATURE/EN VEDETTE:

|

VOL. 9, No. 1, 1-16

I should begin with a warning from the past: history is not on our side in our efforts to ensure that learners control the technologies associated with “the information highway.” It is more likely that technology will control them, and us. We just happen to be in the early phases of the new technol-ogy, when opportunities tend to be open, and optimism abounds. The first phases of printing technology also offered much to many: Bibles written in the vernacular; the penny press informing local and na-tional democracies. What have we got now? A publishing industry control-led by fewer and fewer giants-such as Paramount Communications, which owns Ginn and Prentice Hall, and a mass media dominated by conglom-erates. As they say, freedom of the press belongs to those who can buy one. These days, that costs lots.

When the movie camera was invented, pioneer film makers saw it as a tool for popular culture, where all kinds of people could tell their own stories, frame their own myths. Now, what have we got? A few vertically integrated production-distribution conglomerates and a Hollywood model of production requiring millions of dollars to participate as anyone other than a passive observer. With the advent of cable, there was a similar first wave of optimism, with community cable experiments such as “Town Talk” in Thunder Bay, “Women in Focus” in Vancouver, and Cable 10 in Toronto. Twenty years later, cable is dominated by a few big companies repackaging the same old commercial programming associated with broadcast television. It goes to show you: the medium is the message.

In other words, the social construction of the medium dictates what messages a given medium will carry. That is what we are up against. The fact is that the information highway is by and large a commercial corporate construction with a built-in bias toward information as a product-a com-modity to be consumed. It is not information as the process of informing oneself; it is not a process of communication but of production. The bias is toward information production and consumption, not dialogue. The commercial commoditizing interests have enclosed and come to monopolize every successive wave of new information technologies since the dawn of the modern era, and there is a strong possibility that they will do it again with the information highway. It is possible to resist, possible to create a public-interest community-centred model of learning and education using a variety of information technologies-as these are appropriate to the task. But we have to realize that we are acting inside the belly of the beast. And the beast is always hungry. Hungry for new things to commoditize, new markets to exploit.

It is also important to realize that the information highway is one aspect of the new world economic order associated with restructuring and deindustrialization. It is a sign of the maturity of the global computer-communications systems that have been growing since the 1970s. These systems reached critical mass and global integration in the late 1980s. As they did, they transformed the economy from an iron- and steel-centred economy to an information economy. In a nutshell, all the formerly separate sectors of the economy-pri-mary resources, secondary manufacturing, and services-have been turned inside out. Where before information was peripheral to the main materials handling, processing, and manufacturing operations, now everything from resource extracting to parts assembly-plus all the form-filling associated with services-has become merely the operations end of huge information systems. These systems are at the centre, driving the increasingly auto-mated operations as extensions of their software.

The Globe recently ran a picture from a convention on automated mining equipment. The photo showed a remote-controlled machine on which a single mine worker controlled two eight-yard scoop trams in a copper mine 450 km away, and 900 metres underground. There were two signs on the side of the system. One said Inco. The other, only slightly smaller, sign said Bell. Computers linked with communications systems allow for al-most totally automated mines, smelters, and pulp mills. They create largely automated fish-processing plants and even automated grain elevators across the Prairies. In secondary industry, they allow for just-in-time manufactur-ing: in the case of Benettons clothing manufacturers, for example, every-thing is keyed from colour and size according to the latest sales data flowing from Benetton’s on-line cash registers around the world. In the auto industry, they allow car-assembly instructions to be beamed from engineering departments in head office directly into the robots on the assembly line in Ontario or Quebec, or Mexico, or, soon, probably Eastern Europe. Similarly, computers linked with communications allow for multi-branch banking, computer-generated insurance, even automated patient-care management systems in hospitals. The computer is the new context putting everything together, “doing it all for you,” as the ad for McDonald’s used to say.

What these changes have meant is a massive erosion of work and employment. Direct loss of jobs occurs as assembly lines from car factories to garment plants are pared down, as management is reduced from 10 layers to 3, and as companies running on pre-automation equipment go bankrupt and others relocate under Free Trade and NAFTA. Between the introduction of Free Trade with the U.S. in 1989 and 1992, 463,000 full-time jobs disappeared in Canada. Automation has left us with protracted high levels of unemployment and jobless economic growth. In Ontario, for instance, companies are making new investments right across the board. But they are investing in new machinery, not new employment opportunities. But the most profound and pervasive of the effects of this transforma-tion, I think, is a polarization of work: the good jobs/ bad jobs scenario-with technology as the unseen hand in the equation.

I first documented this in Fastforward and Out of Control. In all three sectors, the middle ranks of employment-skilled machine workers, pro-fessionals and semi-professionals, administrators, senior clerical workers, and general managers-were being decimated. For example, in processing and manufacturing, 220,000 jobs disappeared at wage levels ranging from $6.75 to $20 an hour-half of them in the over $13.50 an hour range. Some growth was occurring at the highest wage levels-the mega-buck executives of the late 1980s and technology-assisted professionals. But the biggest job growth has been occurring at the lowest wage levels- in manufacturing and processing as well as in clerical, sales, and service. Finally, the role of technology in this polarization is being recognized in official circles.

A Statistics Canada report released earlier this year, called What’s Hap-pening to Earnings Inequality in Canada (Morissette, Myles, & Picot, 1994) documents the ongoing erosion of middle-class jobs. But the most dra-matic changes show up in the bottom ranks of income. Men in the bottom 20% of earners saw their real earnings drop by 16% between 1973 and 1989. Broken down by age, the impoverishment is even more dramatic. Young men (between 18 and 24 years old) took the biggest drop. Their real earnings fell by a whopping 26% between 1973 and 1989. Women’s dropped by 12%; but they were low to begin with-partly because of women’s historical concentration in low-paying and part-time jobs. High rates of unemployment and poverty-level underemployment-this is the reality of Generation X, which is quickly expanding into a two-generation phenom-enon. As Kurt Cobain of Nirvana put it in one of Nirvana’s most popular songs: “I feel stupid and contagious. Here we are now, entertain us.” I find it ironic that in my generation, Janis Joplin killed herself through a drug overdose. In an age of exponential expansion, she overdid it. Twenty-four years later, in an age of painful contraction, Kurt Cobain shot himself in the head.

I mentioned part-time work. This touches on the pervasiveness of the new kind of job on the short end of the polarization stick: the “McJob.” It has become a generic word for all the jobs that are mindless extensions of computer systems. You no longer work for a person. You work for the machine. You are the fingers on its keys, its smiling human interface. It also links into another aspect of the polarization-deinstitutionaliza-tion. With sophisticated information systems supplying the context for organizing and scheduling the work to be done, corporations and govern-ment departments can centralize control, decision-making, and innovation while drastically decentralizing operations. Deinstitutionalization makes possible both the “virtual corporation,” which comes into existence wherever a representative can plug in his or her laptop computer and get on-line; and, as a corollary, it also makes possible the “virtual workplace.” It might be your home or a satellite workshop. It might be anywhere.

Deinstitutionalized workers are the fastest growing segment of the labour force. They include professionals on contract and countless others in telework. This, I suspect, is growing the most, and will grow the fastest, as the information highway delivers more banking, brokerage, and retail services on line-and as it gets into processing transactions for video-on-demand, training-on-demand, inter-active shopping, and so on. (I can also see these services becoming more and more popular as more drive-by shootings and more hard-luck hustling street people transform the formerly friendly common places of our communities into a problem-filled preserve of the have-nots and the dispossessed of our society. The so-called Haves, certainly in the U.S., are beginning to feel safer staying home.)

Not surprisingly, U.S. companies such as Hughes Corporation’s Direct T.V. and the giant home-shopping cable network called QVC have estab-lished quite a lead in this new information economy. Omaha, Nebraska, is called the “1-800 capital of the world” because of its huge involvement in teleretailing and telemarketing. A full 40% of the city’s workforce is involved in this form of employment. The hotel chain Best Western has taken telework one step further. When you or I phone to make a reservation, the call is routed into a U.S. prison where inmates act as reservation clerks on keyboards installed there. It is an interesting variation on the notion of the “captive labour pool.”

Similar telework-and the “McJob” in general-represents an interest-ing variation on the notion of a glass ceiling blocking advancement and career development. I call it the “silicon ceiling.” All this restructuring is happening in a context of globalization. I can-not elaborate on that topic here, but I do want to mention it to finish painting the broader picture of what constitutes the larger context for your work in education and training. Basically, globalization means globalization of the corporate economy- the economy peopled by big companies, such as Alcan, Northern Telecom, Rogers, Canadian Pacific, the big banks, and so on. With global informa-tion systems at their disposal, they can take their money and go anywhere, generating new economic activity anywhere in the world. It is a bit like retinal detachment in the eye. Only in this case, these corporations have peeled off outward, into their own global orbit, leaving other parts of the economic body behind. By that I mean the business of raising kids and educating them, the business of looking after the elderly and the sick, providing housing and clean water, and putting food on the table. These parts of the economy are still here, still rooted in local com-munities.

Yet the money that used to trickle down from the industrial-production part of the economy is trickling down elsewhere now: in Mexico and, increasingly these days, in the former Soviet Union and East Bloc and China. Part of the crisis associated with restructuring is that globalization has made Keynesian economics redundant. That is the larger crisis of our time: having to renew the integrity of local, regional, and even national economies at a time when the tax base for publicly subsidizing these economies is drying up-because globe-trot-ting virtual corporations are trotting off and because of the unemployment and underemployment their management priorities have left behind. It is quite a crisis. And yet the social response to all this seems strangely stuck in adjustment mode. Adjust to the new world economics; adjust to the latest technology (i.e., more math and science education in the school system and, after that, more, and more sophisticated, retraining). This attitude prevails, despite the finding that 80% of high-school and univer-sity graduates have taken some computer training either at school or on the job but only 50% use computers at work. And most of these only use computers for simple jobs like data-entry and word processing (Lowe & Krahn, 1989).

Then there is the finding of a study by Jerry Paquette at the University of Western Ontario (Paquette, 1991) that found that given the pervasive-ness of the “silicon ceiling” and of the McJob, there is virtually no eco-nomic payoff to finishing high school or even to getting a college diploma in many cases. The payoff only begins when you have at least one univer-sity degree and can position yourself on the other side of the computer-systems divide where you begin to work with technological systems, not just for them. In other words, what Paquette found is that high school dropouts are not being dumb. I recall when I toured the new Chrysler plant in Brampton, Ontario, in the late 1980s, management had talked about the knowledge workers they would need to run the new place when it opened. But when I got there, many skilled workers had quit from boredom and were being replaced by high-school dropouts. As one guy told me, the work is the equivalent of changing light bulbs.

And, finally, a recent survey of 70,000 adults using the Daily Bread food bank in Toronto found that unemployment was the biggest single factor for people using the food bank. Since 1990 75% of them had lost jobs. Their job skills? As Michael Valpy reported in the Globe (April 6,1994): “Those out of work are more likely to be computer-skilled than labourers; more likely to be teachers than taxi drivers.” The largest single category was office workers-at 19% of those surveyed, followed by construction workers (at 17%) and professionals (at 14%). The crisis of reconstruction and economic renewal we are faced with is also a crisis of values: What values do we choose to govern ourselves and be governed by in education and elsewhere: technical systems values, such as faster, cheaper, more productive, and more competitive or human values, such as participation, social justice, equity, and community? In other words, do we want education to develop a whole person to participate fully in her society or education to fit people like widgets into the machine, into the latest McJob opportunities in an increasingly homogenized global systems economy?

But beneath that crisis lies what I consider to be the root crisis of them all: a crisis of perception and language. Every time you talk about “human interface,” “human capital,” or people’s “input” and “feedback,” you diminish the importance of people and increase the importance of technological systems, and you make yourself more receptive to systems-given perceptions. Every time you tolerate it when a CBC announcer says that the “stock markets are more comfortable today,” you accede to the importance of these systems over the importance of Kurt Cobain and Generation X. Possibly two generations of young people- unemployed or underemployed-are forced to live at home with their parents or to live on the street, disenfranchised from their society, and excluded from consid-eration by those same CBC announcers who tell us how comfortable the stock markets are today.

Now I want to turn to the information highway because I think that the key to your response to the larger crisis lies in how you respond to these technologies as they affect your work and working environment. And that, I think, depends on your ability to perceive what is going on with the information highway on your own terms. In other words, if you can throw off the ball and chain of preconceived perceptions about the “information highway” and begin to rephrase the issues and questions from the perspec-tive of people as learners and teachers. If you can cultivate a human-centred, learning-community-centred perspective and analysis here, then I think there is hope for the larger picture. So, getting back to “the medium is the message,” What is the medium? Is “highway” the best way of describing it?

Well, yes and no. Postwar highways and superhighways became major arteries of communication. They also stimulated all kinds of industries from manufacturing to services. And they transformed the social landscape, creating whole new institutions, for example, suburbs and industrial parks. But notice the emphasis on movement for the sake of movement in the highway metaphor. Highway focuses our attention on the pipelines of information associated with cable, telephone lines, satellites, and fibre optics. It simply assumes the content. The metaphor introduces almost a technological imperative to network, to be in touch with that group of Japanese school kids as happened with Safari ’94 on Earth Day. Hook up, hook up, log on. Hurry up. But why? It costs money. In Newfoundland, someone connected to the schoolnet there estimated that if they had to pay for the hook-ups they use, it would cost $40,000 a month. The organizers of the Toronto Freenet estimate it will cost $3 million for the first five years. Ah, but Rogers has come to their rescue, offering free hook-ups worth $7,000 a month as a donation-in- kind for those five years. And then? For many, too, the experience of hooking up is a big disappointment. But why should that surprise us when the highway metaphor puts the emphasis on the pipeline, on the transmission, and on the hook-up and not the quality of the content.

But perhaps the greatest drawback of the highway metaphor is that it is industrial age thinking where the technology is in front of you and tangible. Paved roads, cars, trucks, gas stations, and so forth. But with the global information systems into which television, cable, and interactive games and transactions are now being plugged, the important technology is invisible. It is the webwork of communication lines and switches behind the walls, in the air, and so on, integrating all kinds of information and media technologies into an all-enveloping skin. In the post-industrial age, the machine is no longer in front of us. Or rather that is only a small part of it. Now, the machine is all around us.

We live in the machine. That is why we have things like virtual cor-porations, virtual classrooms, virtual communities, and deinstitutionalized workers, teachers, students, and so on. The huge machine represented by global-now converged multi-media-information systems represents the new organizing context, the new all-pervasive institution within which everything comes together in space and time. The systems and applica-tions software are what drives it, what makes sense of it all. Sense to you and me? We need to make sure we have a way to check this out.

Marshall McLuhan said that the new electronic communications sys-tems were becoming our new living environment, our new “surround,” he called it. He also said that they structure our consciousness, working us over with their hidden assumptions. Not only is the medium the message, he said, it is also the massage. So, we are talking about more than highways you can choose to get onto or not, depending on how much gas you have got and whether you have a car. We are talking about enclosure in the global webwork of information systems associated with the new world economic order. It is a webwork of connectivity (and enabling or disabling software) that is already well entrenched through the business, government, research, and academic institutions of our society, and it is now being extended into health and educational institutions and through the community into people’s homes.

What hidden assumptions are being extended invisibly through the walls, floors, and ceilings as these hook-ups go forward? When I interviewed Andrew Bjerring, CEO of CANARIE, for an ar-ticle on the information highway, he spoke enthusiastically about the fact that “education and health facilities are becoming much more integrated into the information infrastructures.” But are they being integrated on their own terms, so that these infrastructures reflect the true goals of education and health, with their twin priorities of public service and the public good? Or, are these institutions in danger of being transformed by the values governing these infrastructures and their operating software? It leads us to the next question: Whose information infrastructures are these? Who is building and designing them? Who is drafting the policies by which they will be governed and managed to ensure they are used in our interests?

Some people contrast the cable model, with its closed system and centralized control, to the more open architecture of the telephone, with its distributed switches empowering local users. But both cable and telephone companies are also grounded in the commercial model, which treats com-munications as transactions and information as a commodity being sold or distributed. It is in the phone companies’ self-interest to charge for units of information moved and for seconds of access time. Yet without a flat monthly or yearly fee, the free flows of information associated with schoolnets and the Internet generally could wither if not die out completely, and the flows will funnel down to only those items previously approved in the budget: that is, pre-packaged learning materials or courseware.

Andrew Bjerring told me that his preferred metaphor for the informa-tion highway is “information mall. It is a virtual mall,” he said, “where all the activities, including the cultural and social, take place.” But all, we should note, all enclosed within a commercial space. Garth Graham, on the other hand-a consultant associated with Telecommunities Canada and an Internet enthusiast-wants the informa-tion highways to be an “information commons.” Commons or mall? Which will it be? One way to check it out is to see who the players are and which ones are in strategic decision-making posi-tions, both regarding public and private investment and public regulation and policy. On the commercial side, there are a lot of heavyweights: Rogers and McLean’s have just merged into an interesting carrier-content combine. But what is even more interesting, though less publicized, is Rogers involve-ment with Microsoft to develop an interactive black box that will decode all the information coming to people’ s homes and schools as part of the “500-channel” universe. Everyone knows Microsoft, run by Bill Gates. Microsoft is the name in computer software. It controls 80% of the world market for PC operating systems and 50% of the applications software running off those systems. That is an astounding strategic strength. It means we should take Bill Gates seriously when he says he hopes to provide the brains running the informa-tion highway (i.e., its main operating system and maybe some of its appli-cations software too). Meanwhile, he has formed an alliance with Intel, the world’s biggest microprocessor manufacturer, and another one with Gen-eral Instruments, which makes T.V. converters. He is negotiating another with Time Warner. Along the way, he snapped up the hot little Montreal computer animation company, Soft Image, which animated the dinosaurs in the movie Jurassic Park. Microsoft is worth $23 billion-more than G.M., Xerox, or IBM. And it is investing $100 million a year in the information highway while we are holding bake sales to build learner-appropriate education networks. Rogers’ main rival in Canada is Stentor, the alliance of major Cana-dian phone companies. Stentor is working with Digital Equipment in the U.S. to develop its own dispatch/decoder system. Their plan is to create regional “media service centres.” Supercomputers in these centres will process customers’ demands-everything from log me into my bank to bring me X course offering from Carleton University’s Instructional Media channel, or T.V Ontario’s Learning Solutions Group, or B.C.’s Knowledge Network. The supercomputers will then beam out a, b, & c multi-media learning packages or movies or orders for Pizza-pizza-at a rate of 200,000 bytes per second to thousands of sites simultaneously-while a home re-ceiver would store the incoming information in a buffer, decompress it, and project it onto home receiving devices, computers, televisions, fax machines, printers, and so on.

Carleton University is involved in a pilot project with Stentor, which is delivering one of Carleton’s 45 video courses to 500 distance education learners. Université d’Ottawa has been offering course-support materials, such as NFB films. But Stentor is also involved in an alliance with MCI, one of the biggest long-distance communications carriers in the U.S., just as Unitel (which is partly owned by Rogers and partly by Canadian Pacific) has formed an alliance with AT&T-through which AT&T now owns 20% of Unitel. I worry at this continental integration-not as such, but for the biases it can bring. I worry that we will get file-server centres that offer a better deal on, and easier access to, American educational packages than they offer those provided by Carleton, or the Knowledge Network, and so on. Strategic policies and alliances are needed to prevent this integration from happening, in my opinion.

So where is the Internet model in all this? Well, it is very much in danger of being enclosed by these continental-scale commercial interests. This is happening not only through the colossal investments being made by the corporate sector- including Rogers’ move to subsidize the Toronto Freenet and U.S. West’s move, in alliance with the Corporation for Public Broadcasting in the U.S., to donate $1.4 million to computer networking groups in the States. It is also happening through the privatization of Internet’s infrastructure and related management. In the U.S., Bell Atlantic is one of the companies bidding to take over running the core infrastructure from the National Science Foundation, which funded the original network of research scientists and which, along with the universities involved, has essentially subsidized Internet’s amazing growth in recent years.

In Canada, this prize went to CANARIE, a private/public sector con-sortium, which the government has adopted as its chosen mixed-economy instrument both for upgrading and privatizing the Internet infrastructure and for supporting the Information Highway through our tax dollars. I began to worry when I discovered that the minimal entry fee to participate in this consortium was $2,500 a year. What schoolnet or freenet can afford this price of admission? My next worry was when I discovered that setting this exclusionary fee was part of the by-laws set down by the founding members of CANARIE. Of the 19 founding members, only the University of British Columbia and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research were from outside the cor-porate sector, outside the commercial model. The others were Bell, Unitel, Northern Telecom, IBM, Hewlett Packard, Unisys, Newbridge, Stentor Resource Centre, and Canada Trust. We cannot roll back history and prevent the enclosure of the com-mons. The commons has already been enclosed, has already been commer-cialized. We are in the belly of the beast. Some call the beast the techno-logical dynamo or the technological imperative. Others call it imperial-ism-specifically, American imperialism.

Certainly, I think we are on the brink of a recolonization of Canada, with our health care and educational institutions as the primary targets for take-over, not just by services offered by big information-systems con-glomerates moving into education and training but by the mindset associ-ated with the commercial model. In it, education is increasingly trans-formed into educational packages, a commodity to be consumed-and it is less and less a holistic experience in real life, grounded in real commu-nities. How to resist? First, through clear-eyed analysis and, second, through imagination.

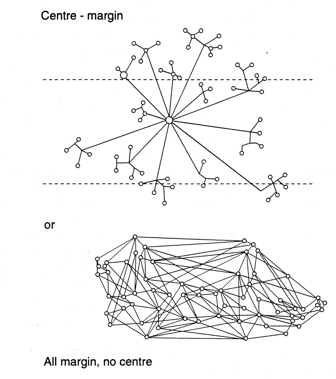

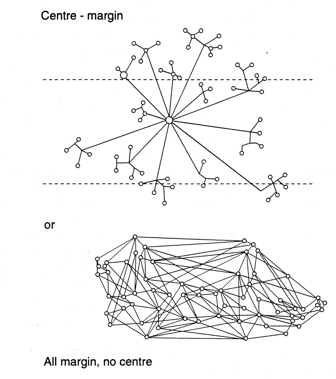

By way of analysis, I think it is critical to understand some of the key structural dynamics in the construction of these technologies. Being an avid student of Harold Innis, who studied the communications technologies of many civilizations from the Egyptians, the Greeks, and the Romans to our own, I draw from his analysis to predict that the bias of the corporate systems is toward the commoditization of every human activity and to do it in a way that will centralize control over large areas and enhance depend-ency, especially on the margins. As strategies of resistance, it is important to offset the commercial commoditizing bias with a public sector bias on information as a public resource and education as a public good. Structurally, it is vital to empha-size and support the margin so it can resist being sucked right into the centre and assimilated by its culture. Since its first occupation by Europeans, Canada has always been on the margins. And our identity has always been wrapped up in simultane-ously participating in the cultures of imperial centres and resisting total absorption by them. Resisting is essential if we are to have a diverse culture in this part of the world: in other words, if we are going to educate ourselves on our own terms, in terms of what is important to us histori-cally and in the present moment, in the local community. Identifying ourselves with the margin, as educators and learners, means ensuring that the information highway is structured and governed so that it will build functionality in the margins and across the margins. Both are critical. At the simplest level, it means trying to equalize the computing power between the centre and the margin (i.e., lots of computer and net-working power on our desks and in our schools, not just in multi-media distribution centres). As I said at the outset, controlling the technology is crucial. Here, it means controlling the structures associated with network-ing and distribution (i.e., controlling the switches so we can distribute things freely, easily, and directly between one site on the margins [a school, perhaps] and another spot on the margins [a library or a school in another community])-without having to have the material approved by a corpo-rate distributing centre, such as the Prodigy network operated by Sears and IBM. Controlling the local switches to facilitate networks of inter-meshed networks will build a society that is all margins and no centre.

It includes the webworks within the community (e.g., school kids operating video cameras and creating a data base, so when it is time for speeches or Science Fair, all the parents who cannot come can log into Freenet to find out when their kid’s speech or project will be on, and then watch it. Maybe even key in questions for the student). Frankly, I would rather put the money into people locally to enrich networking in local communities before throwing everything into global communities.

Enriching local communities requires an open, locally governable ar-chitecture. That is why local freenets are so important-building local computer switching capacity and interoperability between like-minded institutions in the community, as well as from community to community- not community and centre, community to centre. This issue gets to the questions within the question of Access. When people talk access, it is important that it mean more than access to the Information Highway technology. What counts is access to information: the content, which is both communication and dialogue, as well as information as data and product. It means easy, open, ubiquitous movement across the information systems. It also means access to participation: participation in learning experiences and, in the process, maybe creating, packaging, and indexing new information, which can possibly be shared with others or sold. This kind of access is a far cry from just consuming information as an inert product with multiple-choice simulated interaction. It also means negotiating cost structures as much as the software and system structures that facilitate interaction.

We can learn from the experience of community cable. One of the reasons community cable failed is that it was handicapped from the outset by government regulations-regulations possibly informed by vested inter-ests in the corporate lobby. CRTC regulations prevented community cable companies and collectives from sharing and trading and buying each oth-er’s productions. The CRTC said that local programming meant that only locally produced programs could be shown on local cable stations. Yet re-selling is the key to cost recovery and to making enough money so that you can make more programs. And, of course, it is critical to be able to do some buying and selling. Here, I wish to simply flag in passing the fact that big business is keen that freenets should be run on an entirely voluntary basis-no commercial activity, no employment-generating capacity. If this were formalized into regulation, it could cripple the capacity for content creation on the margins just as surely as community cable was crippled by the local-programming rule.

We can also learn a lot from studying the lessons of the UNESCO discussions about the New World Information Order in the early 1980s. We are not drafting a traffic code for a new type of highway here. Whether we are participating or not, what is going on is the equivalent of constitutional talks: drafting the constitution that will determine how we live and govern ourselves in the post-industrial information society. Some of you may know of the UNESCO discussion by the name MacBride Commission. This Commission was part of it, part of the dis-cussions that involved mainly Third World and non-aligned countries try-ing to draft a charter of information rights that would help them to de-velop their own news media for their own citizens and to push back the nearly saturating presence of U.S. news media in their countries. What happened? Well, you might say that the U.S. won that round of negotia-tions over the New World Information Order because they successfully redirected the discussion into a question of access-access to technology, that is to say, American technology.

When I heard that Rogers is giving space and technical support to the Toronto Freenet, I remembered those discussions and I thought cynically: “It is the old, loss-leader idea of merchandising. Get people into the store by practically giving away certain things. Then you have got them.” Here, get people used to the technology, get them integrated into the information infrastructures, with dollars and time invested in using-and relying on- these multi-media systems, and colonization is complete. So one part of the analysis must be to consider seriously saying NO to all these fancy new multi-media technologies-or at least to taking a breather, declaring a moratorium so you can blink and get your perspective straight and can see the forest for the technological trees. We must take seriously their capacity to work us over. We must take seriously the disproportions of power involved.

We must also look at the physical bias of computer technology. Com-puters are not built for synthesis but for breaking things down into infinite numbers of sub-sections. Also, their capacity for dialogue is limited. “E-Mail from Bill” (in the Jan. 10, 1994 issue of The New Yorker) demon-strated this truth to me. On the computer, people talked past each other. The author also noted that it was only when they met in person that real communication began, when they could take each other in as whole per-sons. Not as disintegrated, dismembered parts of sensory experience. I do not mention this example to trash the technology but to em-phasize the importance of clear-eyed analysis and of distinguishing between functional dialogue and real communication, the stuff of real learning communities.

People talk about virtual reality as though it is real; but it is not. It is virtual simulation. We mistake it for reality at our peril. So, the analysis phase should pay attention to the physical weaknesses as well as the strengths of the new technologies, and it should identify centre-margin disparities and how to offset them through public policy and through the negotiation of actual structures. Then there is the second aspect of resistance: imagination; that is, the capacity-which includes taking the time-to think things through on our own terms. This means focusing on learning communities first and fore-most, and only when we have clearly identified what we are for as learners and educators, only then asking what is the technology for? What is the most appropriate place of various information technologies here? In other words, our job is not to focus on the information highways and pipelines but on the content. Our job is to focus on people in communities and what they need to learn to make their way in the world and to participate in renewing the local, regional, and national economy. (Here, I refer back to what I was saying earlier about renewing local economies because I truly believe that educating and learning must become more dynamic and crea-tive, more geared to learning by doing in actual contexts of work needing to be done in the community.)

Meanwhile, our job is to focus on multi-media as a means to an end, not an end in itself. The number of people who have flipped it around amazes me. A journalist who interviewed me last week was full of ques-tions about whether the information highway would produce a more open democratic society. I kept saying “only if.” Only if we negotiate and leg-islate these values and priorities into the structures of the iinformation high-way systems. The constitutional talks and the design negotiations are going on now; principally among big business, with government acting as an administra-tive assistant. We need to create our own parallel discussions, through the Coalition for Public Information, through Internet’s Canada Infohighway discussion group, and so on. From my own experience, which includes participating in some video-conferences, one electronic conference, and teaching a course on televi-sion, I have learned that there is an important place for these new technolo-gies. Good video programming, supplemented by a well thought out learner manual, plus meaningful electronic mail contact with the professor and teaching assistants can be a good learning experience. However, there are limits. Very real limits. There has to be equal opportunity for dialogue through face-to-face on-campus involvement.

If educators work in solidarity with learners, putting the learning needs of people as people first and foremost, I am confident we can ask the right questions and, in answering them, define our own terms for participating in the New World Information Order, making it a place for people, not just technology. Good luck.

Morissette, R., Myles, J., & Picot, G. (1994). What is happening to earnings in-equality in Canada? Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Analytical Studies Branch.

Lowe, G. S., & Krahn, H. (1989, June). Computer skills and use among high school and university graduates. Canadian Public Policy, XV(2), 175-188.

Paquette, J. (1991). Why should I stay in school? Quantizing private educational returns. London: University of Western Ontario, Department of Educational Administration.

Heather Menzies was the keynote speaker at CADE '94, the annual con-ference of the Canadian Association for Distance Education, which was held in Vancouver, Canada in the spring of this year. Heather's presentation was very well received and many participants requested a copy of her address. For these reasons and to accommodate the interest of those who were not able to attend the conference, we include her address in this issue of the Journal.