Infusion, not Diffusion, a Strategy for Incorporating Information Technology into Higher Education |

Jon G. Houseman

VOL. 12, No. 1/2, 15-28

To date information technology has not been widely adopted in higher education. Although I mention a variety of different reasons for why this is the case in this article, I will focus on my own experiences as both a faculty member and an information technology centre co-ordinator. I believe that as a result of a number of changes on our campus, our faculty are more willing to consider information technology in their courses. I also provide some suggestions for faculty development strategies.

Jusqu'à présent, la percée des technologies de l'information dans les milieux de l'éducation post-secondaire a été modeste. Même si cet article relève un certain nombre de raisons qui expliquent cet état de faits, l'accent est néanmoins mis sur mes propres expériences en tant que membre du corps enseignant universitaire et en tant que coordonnateur d'un centre de technologies de l'information. Je crois qu'en raison des nombreux changements qui se sont produits sur notre campus, notre corps enseignant est désormais plus motivé à intégrer ces technologies à leurs cours. Je fournis également quelques suggestions en égard aux stratégies de développement du corps enseignant.

For a number of years, we have heard that computers, or information technologies, are going to change higher education-the way we teach and the way our students will learn. But most of us have seen little evidence to support the claim. I believe that one of the reasons is that we have failed to provide convincing reasons for the majority of faculty to use these technologies. In part, the failure relates to the strategies we currently use to promote the use of information technology and partly it is a failure to understand the adoption profile of any new initiative, especially within the context of teaching in higher education and the application of different media to the unique nature of this type of instruction. Laurillard (1993) provides an interesting perspective on how different types of information technology apply to teaching in higher education.

It is probably the biologist in me, but I have used the word infusion, rather than diffusion, in my title for a specific reason. To me the very different connotations of these two words well describe two different approaches to encouraging and promoting the use of information technology. Diffusion is a passive process. Place a lump of sugar in a cup of coffee, and, if you wait long enough, the sugar will become evenly dispersed throughout it. By the time that happens, would you be satisfied with the final product-a sweetened but cold cup of coffee? Infusion, on the other hand, implies some sort of work, or effort, to speed up the mixing of sugar and coffee-stirring. To follow the analogy, the coffee would be teaching, with a rich variety of blends, flavours, and beans that match the variety of styles, techniques, and strategies that we use when we teach; the sugar would be information technology.

A good example of the diffusive approach to the integration of information technology into higher education is allocating strategic funds to specific projects that, when finished, are held up as exemplars of the use of information technology. With these examples in place, the rest of the faculty are supposed to be ready, willing, and eager to follow along. An infusive strategy goes one step further. When a teacher considers adopting information technology in their teaching, they find in place the tools and training to support realistic initial projects that they can easily achieve. This approach makes no inherent demands that teachers use information technology; instead, when they choose to do so, they are not faced with barriers to their use of these tools.

One of the main reasons I believe that we are finally on the verge of seeing a more widespread incorporation of information technology into higher education is that, until recently, only a select group of users experimented with the computer and its potential use in teaching, not faculty in general. It is the general faculty population whom we must reach, and they are often ignored in efforts to encourage the use of information technology. When we combine this problem with a failure of university administrations to develop a strategic planning process for the use of information technology (Daniel, 1997), the services responsible for supplying it, understanding the dynamics of the adoption of any innovation, and the problem of access to the hardware and software, it should come as no surprise that we have as yet to see general acceptance of information technology at our universities.

So why haven’t we seen information technology and, in particular, computers become more heavily used in teaching? I have mentioned a few reasons, but there are still a variety of answers to that question, depending on who is asking or answering it, and they may conflict. I do not intend to try to identify all the barriers to adoption here, nor do I intend to provide solutions. (For a more in-depth discussion, see Gilbert, 1996.) Instead, I would like to take the perspective of average faculty members considering the use of information technology in their teaching and try to understand what they face when they consider this potential change in the way that they deliver material to their students. I will combine my own experiences as a faculty member who teaches biology with my support service role in creating an information technology centre for faculty development.

The most significant barrier is not new. It is the failure of higher education to acknowledge teaching. In spite of the best efforts of central administrations and faculty associations, the acknowledgment of teaching in academic advancement still remains a poor second cousin to research. It is not a problem created by the use of information technology. It is a problem that has always existed and still needs to be addressed. Simply put, there is no incentive for faculty members to change the way they teach. When a faculty member has adequate, or better than adequate, teaching evaluations and is faced with stiff competition for ever dwindling grants for research, the staple of academic acknowledgement, it is clear where time is better spent. It is not on innovative teaching, which may or may not include information technology. (In the 1997 National Survey of Information Technology in Higher Education in the United States, Green [1997] reports that only 12.2% of the institutions surveyed recognize information technology in the career path of faculty.)

As universities consider providing access to the tools required for incorporation of the new technologies into teaching, they must ask why would faculty want to use them? (Only a third of the campuses in the 1997 survey by Green have a financial strategy for the use of information technology.) As institutions renovate and build multimedia classrooms, what guarantee do they have that the faculty will even turn on the equipment in the room? As support services invest their time and monies into pilot projects with faculty, they must ask whether other colleagues in that department would be willing to do the same and whether they could provide the same level of support the next time around?

In an enthusiastic rush to embrace information technology, we often fail to consider the human side of the equation: our faculty. How will they respond to these new initiatives, and will they adopt the innovations that are available to them?

Perhaps it is best to look first at the dynamics of the adoption of any new product and see what it takes for an innovation to change from being a novelty item to something everyone uses. Such an analysis is done in the marketing of any new product, and there are a few things that we can learn from these adoption curves.

In his original model, Everret Rogers (1995) identified five different categories of users in the successful adoption of a new innovation. I have taken the liberty of simplifying the model so that it includes only three categories: the innovators, the followers, and, finally, the naysayers. Each has an important role in assuring the success of any innovation, and each represents a different part of the adoption curve (Figure 1). The slow initial first phase of the innovators is followed by the middle group, which make up the two components of a rapid increase in users over time, which then slows to the point where only the naysayers, who never adopt the change, are all that are left. I suspect that you can think of a variety of innovations that have affected you already: the VCR, the switch from vinyl to CD-ROM for music, and even the telephone or television can be described using curves such as these. But what about the characteristics of the people found in these three different categories?

Innovators are those who will try just about anything new if they have a personal interest in doing so. From the latest DVD player, to a palmtop computer, or a new piece of software, the innovator will give anything a try, and they transfer this attitude to their teaching. They enjoy being on the leading edge (bleeding edge?), and they will spend their own time to trouble-shoot problems and iron out the kinks in their innovative projects. They can get the ball rolling, but their numbers are not enough to assure the success of the innovation. That falls to the next group: the followers.

Followers are generally interested in the innovation, but they would only consider getting involved after someone else has everything worked out. They are content with a VCR and may even have figured out how to set its timer and clock (a trait many believe would be attributed to an innovator). They might buy a DVD player once they are sure that the standard will hold. Followers are generally less tolerant of things that go wrong, and they want someone else to fix them when they do go wrong. They make more demands on the support system, at least until there are enough of them engaged that they can start to help each other. They often worry about what effects the innovation may have on other things that they do, and they bring this cautious attitude to their teaching. However, the followers are the most important of the three groups. By their numbers, they assure the success of the innovation.

Finally, there are the naysayers, who are not interested in and see no advantage to using the innovation. They are quite content with the status quo. They still do not have a VCR and can be recognized most easily either by the clatter of their typewriter or by the sheath of handwritten papers they have dropped off with departmental secretaries for typing. This group has little or no impact on the success of the innovation unless, of course, they take an active interest in opposing it. Often, too much effort is spent trying to convince the naysayer about the validity of the innovation rather than encouraging the follower.

More than just describing events and personalities involved, the adoption curve provides some clues, warnings, and, possibly, some answers to why technology has not entered the mainstream of teaching. The secret to the success of any innovation is the acceptance by followers. Once they become involved, you start to see changes in the way that things are done. No product or initiative will succeed if the adoption curve fails to move beyond the innovators. But what do we do to assure that the use of information technology will move on to the followers? Unfortunately, often very little.

Most universities focus their attentions on the smaller group of innovators and the projects they develop, regarding them as exemplars for all faculty to see and, by implication, to aspire to. By funding their innovative efforts, often by strategic funds or high profile corporate liaisons, we maintain our innovators at the leading edge of the information technology, and each institution may feel that it has in some way tamed the information technology dragon-after all, we have some people doing some great work!

But this approach can have detrimental effects on the adoption of information technology across the university community in general. As the innovator moves with the leading edge of what information technology has to offer and the follower waits at a stationary point, the gap between the two continues to widen. Where only a few years ago digital presentations in a classroom were considered an innovative target for a follower to aspire to, now it is multimedia, interactive web sites, and creating and distributing course materials on CD-ROMs or by video conferencing. Pity the poor follower who so far has only used information technology to prepare lecture notes and handouts on the word processor. They now have the impression that their starting point will involve creating multimedia, burning a CD, or creating web pages.

Our objective should not be to play catch up for the followers. We should instead be providing a replay of the path that got the innovators to the point where they are now. What did they do that worked for them when they started to use information technology? What tools did the innovators use, and what do we know now about their use and pedagogic effectiveness? If we are to engage the followers, we must provide them with the tools, guidance, and assistance in avoiding the pitfalls and traps that can appear along their journey. We must minimize the risks in their use of information technology and provide them with easily attainable objectives and outcomes.

Information technology is often seen as being fraught with technical challenges and risks. I am often asked if I have to cancel lectures because of equipment failure. That in itself is a valid question, but it is often framed with the underlying implication that teaching with information technology is more prone to some types of equipment failure than teaching with the more traditional media.

What we often fail to realize is that with every medium we use to teach, there is always an element of risk in the visual display of information for students. Chalk and the blackboard pose their own problems, and for those of you who use the medium, you already know the advantages of bringing a few spare pieces of chalk to class or eliminating even more risk by bringing your own blackboard brush. If your university uses acetate rolls on overhead projectors, then you probably know that the most coveted possession a teacher can have is a personal spare acetate roll. Slide projectors may fail to go backwards. These are all examples of risks we encounter when we teach, and using information technology is no different.

It is important that we let the followers know these risks and what has been done to minimize them. We do a tremendous disservice to followers by telling them “it’s easy” or that there are “no problems.” To engage our followers, the information technology we provide for them must be simple, transparent, and easy to use. For example, a computer in the classroom must be hooked up and ready to use. Do not expect the followers to connect cables and wires, align projectors and LCD panels, and map network drives.

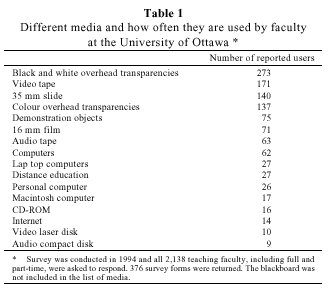

If we can successfully identify the time required and the risks involved, the next question is. What is the most appropriate way to go through the digital change? The answer to the question may lie in what media teachers are already using. In a campus-wide survey we asked faculty to identify the most frequently used media. The overhead acetate, VHS player, and slides (Table 1) ranked among the top three. Two of these items, the acetate and the 35 mm slide, accounted for 48% of the responses.They are both well suited for this technological change using presentation software, such as PowerPoint.

Although the computer can be used to produce the slide or acetate, there is no requirement for the teacher to use a computer in the classroom. As faculty are mastering the skill of creating digital materials, they can still present their content to their students using either the acetates or slides that they are most comfortable with. There is no need to overlay the learning of the software with the use of the computer in the classroom. (In reality, I have seen few professors choose this route. They would rather master the computer for the presentations at the same time that they master the production of the materials.)

The potential success of digital presentation as an entry point to the use of information technology is supported by Green’s surveys of the use of information technology in higher education in the U.S., where this application has increased in use from 15% to 33% from 1994 to 1997. The only other form of information technology that has had a similar rise in popularity is e-mail, which has increased from 7% to 33% use during the same period (Green 1996, 1997), making it a second potential entry point.

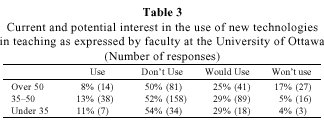

So are faculty willing to become involved in information technology? In the same survey where I asked our teachers what media they used, I also asked them what they would like to learn more about. Using computers or laptops, CD-ROM’s, and the Internet topped their list (Table 2). I was also interested in the demographic of those who expressed that interest. Based on the assumption, valid or not, that our youngest faculty would be innovators and those over 50 the naysayers, everyone in between would be potential followers. Our results (Table 3) showed the highest proportion of faculty who said that they were not using new technologies but would consider it were those under 50 years of age, including both the presumed followers and innovators. These results, and others in the survey, indicated that there was an interest in the use of new technology but an uncertainty about what should be done and how to go about it.

Finding that our teachers were interested in the use of computers might come as a bit of a surprise to those that believe there is an element of technophobia slowing the integration of information technology into higher education. Although this may have been true six or seven years ago, I believe that it is no longer the case. A simple show of hands at any assembled group of academics will show that the majority use a computer for word processing, an application that has become, for most of us, a staple of academic life. We do not live in fear and dread of the machine that provides this application to us. We may, however, not be aware of a computer’s potential for other uses. But the current potential success of information technology in teaching means more than increased acceptance of the computer. It involves other significant changes that have occurred over a few years, allowing university teachers to see the computer as more than just a tool for word processing.

Almost every campus has become “wired,” and fibre optic backbones weave their way through the underground to appear in our offices as an extra jack on the wall, through which, we are told, the campus network and the internet awaits. Prior to this advancement, the innovators were the only ones with internet connections, and they often either paid a premium or used a modem and their existing phone lines to make the required connection.

But where these new jacks are located on the campus can have a profound affect on whether the new technology will be used in teaching and learning by faculty and students. I doubt that many universities have taken this route but, if they only installed connections in the administrative offices of the university and faculty members’ offices were excluded, we can be sure that the followers would never join in. After all, they have no access to some of the other changes that will be discussed shortly.

What is more likely is that the infrastructure has extended to an individual faculty member’s office, making connectivity available to everyone. Evidence that the followers have plugged into this new environment is the rapid increase in the use of e-mail to communicate with colleagues, either across the hall or on the other side of the world. The followers are rapidly becoming comfortable with the use of e-mail, and they use it for their personal and research activities but not necessarily for teaching.

More often, when wiring was done on many campuses, teaching spaces were excluded. Inclusion of these spaces is essential if we expect to see the incorporation of information technology into teaching. There are those that will argue that classrooms will disappear as universities become more “virtual.” But whether or not that happens is not something to be debated here. It is, however, unrealistic to assume that when teachers adopt information technology in their teaching, they will immediately abandon the comfort and familiarity of the lecture format and the classroom that they are accustomed to. By bringing the infrastructure into our teaching spaces, we are able to deliver the hybrid environment that is most likely to be reassuring for the followers, allowing them to experiment with information technology in a traditional setting.

Access to software and hardware has also changed dramatically over the past few years, making it much easier to engage the follower. Five years ago, innovators usually had to purchase their own copies of software for their projects: something that we can never expect the follower to do. Part of the reason for this change is another consequence of the new wiring of our campuses and the networks that have been created. Central servers can deliver the required software instead of users having to purchase their own copies. In addition, competition between software vendors and aggressive educational pricing now makes available to the follower full suites of software for the price of an individual application only a few years ago. But even with all this potential, we have to remain cautious and deliver to the followers the tools that they need along with the training to use them and examples of how to do it. The service and support dilemma is something that all universities face, and the adoption of standards is one of the common ways to meet that challenge.

Just as dramatic as the changes in the software are the changes in hardware. Prices continue to drop as rapidly as the capabilities of the individual machines increase. Five years ago an innovator’s computer was considered “high end” with a video card that displayed more than 256 colours, the potential for sound, a large hard disk, and extra memory to display the requisite graphics of a digital presentation. This is no longer the case. A low end machine today, often costing only a thousand dollars, has the potential to do all the things that the innovators were doing only a few years back. Hardware costs have even dropped to the point where on some campuses, central administrations, faculties, or departments are considering supplying a computer with each position. Such initiatives, combined with the availability of the software, makes it much easier for the follower to start once they decide to make that choice, a choice that must remain theirs.

I believe that across our campuses the followers are beginning to see the computer as more than just a glorified typewriter to be used for word processing. The connectivity of the campus networks has already turned the follower’s computer into a communications tool by their use of e-mail. Software suites have exposed them to different applications, and both innovators and followers are considering the potential of the computer as a tool in teaching, albeit in different ways. The problem for the follower is that it is not clear as to just how this should happen or be done.

With hardware and software in place and the connectivity available, how then do we support the followers in using the computer in their teaching? As discussed earlier, we often provide large funds to the innovators on our campuses for their information technology initiatives to create showcase applications. This strategy of providing funds to a few is often called the narrow but deep approach. By its very nature, it is well tailored for innovators but not for followers. In the case of the latter, a different approach is required-wide and shallow-an approach that does not necessarily involve only providing funds directly to the followers.

The connections to a campus-wide network, the availability of software applications that support teaching, and their delivery to the desktop of the user are all examples of the wide and shallow support of information technology for teaching that should also include information technology centres. If we are on the verge of finally seeing the use of information technology in higher education, it is because we have the combination of interest of our faculty, the infrastructure, and the tools readily available. Is that enough? No, because there is still the necessity for faculty development, assistance, and support for the followers that want to incorporate new technologies into their teaching. If we are to convince them to become involved in using information technology, we must have the support in place.

Workshops are a common way to provide support. In our experience, a successful workshop includes materials relevant to what faculty want to do. It allows faculty to work hands on with a computer, use the software at a comfortable pace, and learn in small groups. It is not that impossible a combination.

Workshops at Teaching Technologies are three hours long, and we never have more than 8 to 10 people attending the two or three sessions given each week. The small size of the workshops might, at first, not appear to be cost effective, but this is not really the case. The potential success of the small customized approach is apparent by numbers alone. Twenty to thirty people a week for 40 weeks of the year results in between 800 and 1200 potential contacts with faculty. Our workshop program over the last 2 1/2 years has seen over 1200 registrants for sessions ranging from an introduction to PowerPoint and advanced techniques of the same software to using the Web and Multimedia and training on how to use classroom computer installations (Table 4).

Date in brackets is the creation date for that particular workshop. Simple good luck probably plays just as much a role in the success of the Teaching Technologies Workshops as planning, but looking back over the last 2 1/2 years, there are a couple of observations that are worth noting.

More often than not the same workshop for an application is used to train faculty, support staff, and students, and it is not uncommon to have all three attending the same session. This combination of registrants can be problematic for a number of reasons. The needs and expectations of the three different groups may vary, and the contents of the one workshop, even if given to the groups separately, may not suit those attending. Many faculty believe that their students often have better computer skills than they have, and there is a potential problem when faculty and students are combined in the same session. Finally, each of these three groups may also have different levels of competence with the software, which further complicates the task of running an effective session.

Our experiences have shown that faculty prefer to learn in an environment that includes their colleagues. Under these circumstances, they are willing to openly discuss their concerns about the use of technology, its applications for their teaching, and their own mastery of that particular application. But, more than making it personally comfortable to attend the sessions, care must also be taken to insure that the instructor is aware of the needs of the faculty members. Computer-savvy undergraduate or graduate students, running workshops, outside agencies, support staff who are unaware of the time constraints, and reasons why faculty are reluctant to adopt information technology can often doom a workshop to failure even before its starts. The relevance of the application to teaching and a discussion of its advantages and disadvantages increases the likelihood of a successful session.

The chances of a successful workshop session are also enhanced if the relevance of what is going on, and how it relates to teaching, is clear to those attending. Our most successful workshops have been ones where, by the end of the session, participants have created something that they recognize as being useful in their own teaching. Or, if it is not quite so easily identified as such, they have a clear understanding of how it could be useful. Successful workshops include conversion of an existing first day course handout into the Home Page on the Web that contains the same material and links to other potential course components, sessions on the conversion of traditional teaching materials into an electronic formats using equipment in the resource room, and using material that the faculty member has brought to the session.

Although there are many other roles or functions that can be identified for an information technology centre, one of the most important is at a place where it is possible to replay the lessons learned by the innovators from their use of information technology in teaching so that the followers can achieve the same results using a more directed strategy and in a shorter time. There are a number of ways that information technology centres can showcase the most effective use of technology in teaching, and in some cases the worst, by providing an opportunity for other faculty members to view what their colleagues have done in their respective disciplines. But more than that, they also validate the efforts of the teachers on our campuses. Having the information technology centre take an active role in this activity assures its ability to maintain an inventory of projects that have been done and of the approaches and technologies that have been used.

The pace with which technology is incorporated into the teaching of our faculty will continue to be overestimated as long as the incentives and acknowledgment of the effort are not recognized. But, unlike the past, the tools required to make the transition from traditional to digital formats are more accessible than ever before. But this unprecedented level of access can be a double-edged sword and without any guidance, faculty can easily create materials that are not visually and pedagogically appropriate. Software agents such as “wizards” may make it easy to create a final product that may have pedagogic and information design flaws when used in teaching. As an example, presentation software wizards create digital slide shows with dark backgrounds and light coloured text that are difficult to use in a 60- or 90-minute class because of how dark the room must be for this type of presentation. (More appropriate is the use of darker text on a light background.) Even the software “default” fonts adopted for projection in the classroom may be inappropriate in both appearance and size.

If these types of pitfalls exist in the simpler applications of information technology, then effective use of the web and multimedia can be even more problematic for the unguided faculty member. Again, it becomes the role of the information technology centre to be sure that the material created is both appropriate and consistent with sound design and pedagogic objectives.

Finally, it is important that information technology provide solutions to pedagogic problems rather than looking for things that technology can do in teaching for the sake of using technology. Traditional instruction design and support is an essential component of the information technology centre, and it is imperative that information technology be part of the multimodal tool kit that our teachers have available to them. Teachers must feel comfortable with the tools that they use, and they have to be assured that any changes they make are appropriate for their own expertise and experience.

There are no simple answers and solutions. But, more than ever, the barriers to the adoption of information technology in higher education appear to have been lowered, and the faculty themselves seem eager to experiment and use information technology. With our content experts, the faculty, now considering the possibilities of information technology, there is the potential for some interesting changes in the coming years.

Dr. Jon G. Houseman

Teaching Technologies and

Department of Biology

University of Ottawa

P.O. Box 450, Station A

Ottawa, ON K1N 6N5

Fax: (613) 562-5237

Telephone: (613) 562-5229

E-mail: houseman@uottawa.ca

Daniel, J. S. (1997). Why universities need technology strategies. Change, 29, 11-17.

Green, K. (1996). The coming ubiquity of information technology. Change, 28, 24-28.

Green, K. (1997). More technology in the syllabus, more campuses impose IT require-ments and student fees.

Gilbert, S. W. (1996). Making the most of a slow revolution. Change, 28, 10-23.

Laurillard, D. (1993). Rethinking university teaching: A framework for the effective use of educational technology. London and New York: Routledge.

Rogers, E. (1995). Diffusion of innovation. New York: The Free Press.