Crossing Boundaries:

|

A. W. (Tony) Bates and José Gpe. Escamilla de los Santos

VOL. 12, No. 1/2, 49-66

New computer and telecommunications technologies offer the possibility of global access to education. In theory, these new technologies should allow potential learners to access any course they want, at any time, from anywhere in the world.

Perhaps most important of all, through widening choice, the new interactive technologies could empower individual learners on a global basis by making education more focused on their needs rather than those of the local providers of education.

That is the promise. But what is the reality? The reality is that inter-national information-technology based distance education depends on developing curriculum that is relevant to learners wherever they happen to reside. It depends on well-developed information technology infrastructures whatever the location of the students. It depends on developing curricula that transcend local cultural and language barriers. And it depends on providing high quality learner support services wherever the learner happens to be. These are challenging requirements, and there are few, if any, guidelines or precedents to follow. It is a challenge that the University of British Columbia (UBC) and the Monterrey Institute of Technology set out to meet in 1997 when they signed a collaborative agreement to develop a set of five courses in the area of technology-based distributed learning. This is an account of how this challenge has been met.

Les nouvelles technologies d'informatique et de télécommunications offrent la possibilité d'un accès global à l'éducation. En théorie, ces technologies devraient faciliter aux apprenants potentiels l'accès aux cours de leur choix à tout moment, à partir de n'importe quel endroit au monde. Plus important encore, la variété sans cesse croissante de contenus offerts par les technologies interactives pourrait avoir un effet d'empour-voiement sur les apprenants à l'échelle globale : l'éducation serait ainsi mieux adaptée aux besoins de ces derniers, plutôt qu'aux besoins des établissements locaux d'éducation.

Telle est la promesse. Qu'en est-il de la réalité ? À ce jour, les programmes internationaux d'éducation à distance fondés sur les technologies de l'information, reposent largement sur l'élaboration de cursus qui soient pertinents aux apprenants, peu importe où ils habitent. Une infrastructure technologique bien développée et accessible aux étudiants de même que le développement de cursus qui transcendent les barrières culturelles et linguistiques apparaissent également comme des impératifs. Enfin, cette forme d'éducation nécessite que l'apprenant ait accès à des services de soutien de haute qualité, peu importe où il se trouve. Ces conditions sont exigeantes et il n'y a que très peu d'exemples à partir desquels s'inspirer en cette matière. Il s'agit d'un défi que l'University of British Columbia (UBC) et le Monterrey Institute of Technology ont entrepris de relever en 1997, en signant une entente de collaboration portant sur le développement d'une série de cinq cours dans le domaine de l'éducation à distance basée sur les technologies. Le défi a été relevé. En voici le compte-rendu.

New computer and telecommunications technologies offer the possibility of global access to education. In turn this global access offers the possibility of a truly global classroom, unlimited by race, religion, or nationality, with multi-ethnic courses, students, and teachers. Teachers and students can be drawn from many countries and study the same course together at the same time. Through widening choice, the new interactive technologies could empower individual learners by providing an education that focuses on their needs.

Lastly, because these new technologies encourage active learning and interpersonal communication independent of time and distance, they can encourage the development of higher order learning skills, such as critical thinking, knowledge construction, and collaborative learning. The University of British Columbia and the Monterrey Institute of Technology set out to meet the challenging requirements of international information technology-based distance education in 1997 when they signed a collaborative agreement to develop a set of five courses in the area of technology-based distributed learning. This paper is an account of how this challenge has been met.

The Monterrey Institute of Technology (ITESM is the Spanish abbreviation) is the largest and one of the most prestigious private universities in Mexico. Its founder deliberately modelled it on the Massachussetts Institute of Technology. It is a remarkable institution by any standards. It has 27 campuses throughout Mexico, with an additional 18 local centres in other cities and 5 centres in other Latin American countries.

As well as conventional face-to-face teaching at the local campuses, ITESM provides distance teaching through a separate component called the Virtual University. Since 1989, ITESM has been using satellite television transmission to deliver lectures to all the campuses within the system. The distance education initiative has been consolidated into the Virtual University since 1996. The Virtual University started as an internal training program for its own faculty in order to raise the academic standards of the campus teachers (many faculty in Mexican universities lack doctorates or even master’s degrees in their subject area). The Virtual University now offers 12 master’s degrees, one doctoral program, and terminal and hallmark undergraduate courses.

In 1996, the President of ITESM approached the President of the University of British Columbia with the suggestion for a strategic alliance between the two institutions. ITESM has been developing strategic alliances with a number of North American institutions. UBC was seen as a potential partner for several reasons. One is its strong links with Asian countries. For its business and engineering students in particular, ITESM was looking at ways to strengthen its Asian networking. Second, UBC is an attractive institution for student and faculty exchange in terms of its research capacity and location. Third, the Virtual University component was looking for a potential partner that could provide leadership and expertise in distance education and, in particular, in the area of interactive technologies, because ITESM was anxious to make the transition from the remote classroom model of distance education to networked multimedia. Last, ITESM was anxious to develop stronger links with Canada. As one of its staff remarked: “What Canada and Mexico have in common is what is between us.” Put another way, many staff at ITESM felt they could have a more equal partnership with a Canadian institution.

There were also potential benefits for UBC. UBC had focused its international activities on East Asia. However, the NAFTA treaty, encouragement from the Canadian federal government, the large and burgeoning Mexican higher education system, and the country’s relative proximity, was forcing UBC to pay more attention to Mexico in particular and the Latin American market in general. Moreover, ITESM has very strong links to major Mexican companies, particularly in mining, manufacturing, and agriculture. These companies were seen as potentially valuable opportunities for internships or job placements for UBC students. ITESM also has several valuable research facilities in areas such as aquaculture, forestry, and agriculture that would be attractive to UBC for student and faculty exchanges.

As a result, a number of visits took place between senior managers, with trips both to Monterrey for UBC staff and to Vancouver for ITESM staff. These visits resulted in a general agreement for a strategic alliance. One of the elements of this agreement was distance education. In particular, an agreement was signed on June 21, 1997, between the Virtual University of ITESM and the Distance Education and Technology unit of UBC for the development and delivery of five courses in technology-based distributed learning.

Like many universities around the world, UBC is undergoing significant changes in teaching methods as a result of the introduction of new technologies, particularly the World Wide Web but also CD-ROMs and, to a lesser extent at UBC, videoconferencing.

These developments are increasingly being referred to in Australia as “flexible learning” and in North America as “distributed learning.” The Institute for Academic Technology, University of North Carolina (March, 1995) has provided a useful definition of distributed learning: A distributed learning environment is a learner-centred approach to education, which integrates a number of technologies to enable opportunities for activities and interaction in both asynchronous and real-time modes. The model is based on blending a choice of appropriate technologies with aspects of campus-based delivery, open learning systems and distance education. The approach gives instructors the flexibility to customize learning environments to meet the needs of diverse student populations, while providing both high quality and cost-effective learning.

It is clear that such developments are having a major impact on faculty, university and college managers, and government decision makers. Within the Distance Education and Technology unit, we believe strongly that these developments have major implications for the training and professional development of faculty, instructional designers, and managers.

This view was shared by the management at ITESM. Prior to 1996, ITESM had already started planning a Master’s in Educational Technology aimed mainly at their own faculty. However, although they were able to develop 7 of the 12 courses in the program themselves, they were looking for another 5 courses that focused on new developments in technology-based teaching. Indeed, they had approached Tony Bates before the strategic alliance was initiated to see if he was willing to help develop some courses in this area.

UBC’s Faculty of Education had only one or two courses on distance education at the graduate level. Although one or two faculty members had some experience in developing distance education courses, and there were one or two electives on distance education, there was no program in either distance education or educational technology within the Faculty. However, it was receiving an increasing number of requests from students who wanted to do research theses in the area of distance education and technology-based learning, and there were several members of the Department of Educational Studies who believed that it was important for the Faculty as a whole to take a greater interest in this area. There was, therefore, support and interest within the Faculty of Education for such an initiative.

Before embarking on a new program, though, we looked at the competition worldwide. There were plenty of institutions offering mainly technical support to faculty on-campus through faculty development office seminars and workshops. There were several institutions offering generic training in multimedia, such as Sheridan and Seneca Colleges in Ontario, and UBC itself offers a Certificate in Multimedia Studies and a Certificate in Internet Marketing through another Continuing Studies department. The Ph.D. program in Educational Technology offered by Concordia University has been a regular supplier of high quality instructional designers. However, it is an on-campus program requiring residency in Montreal, and at the time we were doing our market research, it was also suffering from the loss of critical teaching staff. All these programs are offered on a face-to-face basis and none except Concordia’s deals specifically with pedagogic or instructional issues in using the new technologies.

With regard to programs available at a distance, we located several key potential competitors. Athabasca University in Alberta offers a Master’s in Distance Education at a distance as does the Open University in the United Kingdom and Deakin University in Australia. However, while each had one or two courses dealing with media or technology, it was not their main emphasis. Furthermore, their focus was entirely on distance education not on distributed learning.

The closest competitors appear to be the University of Sheffield in the UK, which offers a Master’s in Networked Collaborative Learning; Boise State University in Idaho, which offers a well regarded Master’s in Instructional Technology over the Internet; Nova South Eastern in Florida, which is a private university in the process of developing a distance program in distributed learning; and the University of Southern Queensland, Australia, which has a graduate certificate program in open and distance learning. In addition, we found many Web-based courses on how to use the Web for teaching. Most of these, however, focused entirely on the technical aspects of creating Web pages and graphic design and, at best, offered very low level or simplistic educational guidelines (e.g., “don’t put too much information on a page”). Many of these “courses” were being offered by people who themselves were very new to online teaching, and while they were valuable in capturing some of the lessons that had been learned, in our view such courses were not sufficiently grounded in educational theory or research.

Although there is some competition out there, and more is likely to come (for instance, California State University is planning a program in a similar area), at UBC we felt that it was worthwhile to launch a new program for the following reasons:

The five courses being developed for this program are as follows:

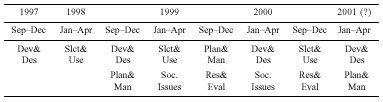

Details of each course are available from the program Web site at: http://itesm.cstudies.ubc.ca/info/>. The program schedule is as follows:

Although there is a logic in the sequence of courses, students can enter at any point in the program. The first course (Dev&Des) was offered in September 1997. The second (Slct&Use) was offered in January 1998. Two courses (a repeat of Dev&Des, and Plan&Man) start in September 1998 and two (a repeat of Slct&Use, and Soc.Issues) start in January 1999. For ITESM, all five courses are available within their Master’s in Educational Technology program (12 courses in all), four are available within their Master’s in Management of Educational Technology, one course is available within their Master’s in Education, and four of the five courses are available in their Ph.D. in Education.

For UBC, the five courses are available as electives within the Faculty of Education’s Master’s in Education program. However, students must be fully registered students within the master’s program, which has a residential requirement.

The courses are also available through UBC either as single non-credit courses or as a post-graduate Certificate program in Technology-Based Learning for which there is no residence requirement. Students taking the courses for completion of the Certificate in Technology-based Distributed Learning must pass the assessment on each of the five courses. Students may also audit courses, that is, they pay full fee, have access to all the materials, online discussion, and tutoring, but they need not submit assignments. Audit students do not qualify for the certificate. All UBC students, whether in the master’s program, certificate program, or taking a single course, follow exactly the same curriculum, take the same assignments, and are assessed at the same level.

Each course is 13 weeks in length and is equivalent to a three credit graduate course, although the Mexican semester tends to be 16 weeks long. (There are some difficulties in co-ordinating start and end dates between the two institutions.)

The courses are designed primarily by a team of staff from the Distance Education and Technology unit (DE&T), Continuing Studies Division, UBC, under the academic leadership of Tony Bates. Dr. Mark Bullen and Diane Janes, both courses developers in DE&T, together with Tony Bates, are responsible for the content of the courses and for tutoring the UBC registered students. The “content” team is assisted by an Internet specialist (Chris Brougham), a graphic designer (Sheila West), a desktop editor (Alan Doree), and a course administrator (Heather Francis), all from DE&T, and a librarian (Jo-Ann Naslund). The academic co-ordinator for ITESM is Dr. José Gpe. Escamilla de los Santos, assisted by several tutors from ITESM. Course team meetings are often done by video-conferencing between UBC and ITESM.

The courses use the following technologies:

Much of the most valuable material, even in this subject area, is still available as printed material only. We decided to rely on selected textbooks and to distribute duplicated copies of selected articles rather than scan everything into the Web for several reasons. One major reason is that we can get copyright clearance within two weeks for most printed material through the Cancopy agreement. However, this agreement does not cover materials for distribution over the Web. To obtain copyright clearance for Web distribution means contacting the copyright holder directly, which is time-consuming, slow, and expensive. In addition, permission is often refused. Second, we find students often print out locally long articles accessed through the Web. Providing them with print versions then is more convenient for them. However, we shall discuss later some of the major problems that arose from the decision to rely heavily on printed material.

Although it would have been possible to use off-the-shelf software, such as WebCT, we decided to develop our own interface design for the Web site. The content is common for students in both institutions, but each institution has its own discussion groups, and we wanted to develop a unique look and feel for these five courses. We have deliberately kept the design simple and avoided the use of unnecessary graphics to ensure fast access speeds. We also hired an interface designer to ensure easy and intuitive navigation of the site. (Go to http://itesm.cstudies.ubc.ca/info> and click on any one of the courses to see an example.) In one course we used a CD-ROM because we wanted to show a variety of uses of multimedia, and it would have taken too long for students to download and interact with the material over the Internet.

The Web site for each course is password protected for security and financial reasons. Students are issued an ID and password when they pay their fees. ITESM issues its own passwords.

For the discussion groups, we use an off-the-shelf program called Hypernews. We chose Hypernews because it is reliable, it is easy for students to use (they do not need to use HTML, for instance), and it is free. However, it does require someone with Unix programming skills to organize the individual discussion groups. We have our own advanced Web server, with a complete back-up system, and direct access to a high speed on-campus fibre network with high speed links to the local Internet node.

The design of the discussion forums varies from course to course. In general, though, there is a non-academic forum (international café) and a general academic forum open to all students and staff, then a set of course related, topic-based discussion groups, each with one tutor and approximately 15 to 20 students. We have managed so far to maintain a maximum of 1:20 tutor:student ratio for UBC students. To keep this rato we have occasionally had to go outside UBC or ITESM to hire additional tutors with the necessary subject expertise. Also we try to have up to three guest tutors for each course. They come in for one week each to moderate the general academic forum. These guest tutors are usually authors of the required texts.

For the ITESM students there are also three or four video conferences per course from the team at UBC, relayed by satellite TV to the various ITESM campuses. Students registered with UBC, who can access the UBC site during the times of the transmissions, also attend. ITESM pays the technical costs for the broadcast videoconferences. The course content is in English (at ITESM’s request; it wants its students to be fluent in English in this area). Some of the ITESM online discussion groups are in Spanish; others are in English. ITESM is responsible for enrolling, tutoring, and accrediting its own students. UBC provides assistance and guidance to the ITESM tutors. UBC has developed a tutor manual and has a “closed” online discussion group for both UBC and ITESM tutors. UBC also develops guidelines and explicit criteria for marking assignments.

Some assignments require students to work collaboratively, with one student from Canada, one student from Mexico, and one student from a third country working as a team. Assignments generally require students to apply course content to their own working context, and at least one assignment must be done individually. There are generally three assignments per course but no proctored examination.

These courses had to be designed from scratch since there was no existing curriculum. It was a particular challenge for the first course offering (Dev&Des, 1997) because there were only 12 weeks from the signing of the contract between UBC and ITESM and the opening of the course. The last part of the first course was still being developed while the first part was being offered.

However, because these are graduate level courses and require a good deal of reading, research, and discussion on the part of students and because the Web was used primarily as a study guide, at least on the first course, these courses needed less development time than many of our print-based undergraduate courses. Nevertheless, with a new course being developed each semester, another two courses being delivered, and a third being revised, all at the same time, and with the core team also engaged in other work in a very busy department, the pressure has been intense.

The Virtual University component at ITESM has relative autonomy to approve its own courses, so from ITESM’s point of view academic course approval has not been a major issue. This was not the case at UBC. DE&T is a service unit. Responsibility for content for distance education programs lies with the Faculties. In this instance, the Faculty of Education at UBC did not have sufficient faculty resources to mount these courses, and, in any case, it was specifically the content expertise within DE&T that ITESM wanted.

Fortunately the main academic co-ordinator from DE&T was already an adjunct professor within the Faculty of Education, and another member of the core team in DE&T had just obtained his Ph.D. within the Faculty. Normally, a new credit program would have to go through Senate for approval, and at UBC this process usually takes at least two years. However, there is a mechanism within the Faculty for offering experimental courses on a limited basis at a master’s level. The first three courses are being offered within the Master’s of Education program on this basis. The Faculty has set up its own academic approval committee to review these courses. Each course is approved individually by the Faculty approval team, while preparation is being made to have the set of five courses formally approved by Senate. (One disadvantage of this creative approach to academic approval is that the UBC course numbers for experimental courses are temporary. Thus, for the second offering of the first course, we found that the same course number is now shared with “Feminist Post-Colonial Pedagogy,” which may cause some confusion for students.)

UBC also recently established a fast track approval process for certificate programs. Provided that the certificate program has been approved by the relevant Faculty, it does not need to go to Senate. Thus, although the courses are the same, a separate approval committee for the certificate has been established with the chair of the Faculty academic approval committee also on the certificate approval committee.

We knew from the outset that ITESM was expecting substantial numbers of enrolments for the first course (200 students was the first rough estimate). Although we had done a quick and dirty market analysis for the rest of the world, we really had no idea how many students from elsewhere were likely to enrol. We needed enough students to cover our costs. However, we did not want so many that we could not cope with the numbers. Furthermore, because we could not advertise before we had academic approval, we had only three weeks during August to advertise for the first course.

We decided at UBC that since students would need Internet access to take these courses and since they were aimed at professional development, for the first course we would advertise solely on the Internet through professional list servers, such as DEOS-L. We had more time for the second course, and we were able to place advertisements in the Canadian Association of University Teachers newspaper.

For the second course, ITESM developed an agreement with the Simon Rodriguez Experimental University in Venezuela for delivery of this course into five of their campuses (two in Caracas and one each in Valencia, Barcelona, and Barquisimento).

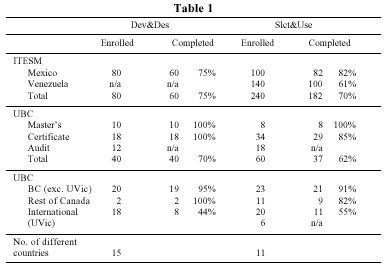

It can be seen then that the first course had a total of 120 enrolments, 80 through ITESM and 40 through UBC. The second course had a total of 300 enrolments, 240 through ITESM, of which 140 were enrolled through Simon Rodriguez Experimental University and 60 through UBC. Just over half the students registered through UBC came from Canada, and the remainder came from 11 to 15 different countries. Certificate and audit students significantly outnumbered master’s students. Of those students that registered for the first course with UBC, 14 continued into the second course. We have defined “completion” as those who registered and paid their fees and who also took the assessments and reached a pass mark, or better. All the UBC master’s students completed successfully, and, in all, 70% of UBC enrolments completed the first course and 62% the second course. Most of the non-completers were audit students who did not intend to submit assessments but who nevertheless continued to participate right through the course. It can also be seen that international students were more likely to audit or not complete than Canadian students.

These figures do not include UBC withdrawals from the course. We had as many as 25 students who wanted to register for the second course but had to withdraw because they had difficulties in securing financial support or because they realized that the course required more work than they could manage in the time available to them. However, only two students withdrew after fee payment, both for personal reasons.

A full evaluation of the first course has been conducted, and another article will deal more extensively with the design and evaluation issues arising from these courses.

ITESM has its own intranet between campuses, reliable server and network technology on campuses, and a dedicated Internet connection from Monterrey into the United States. Therefore, most students had reliable service when accessing the courses from the ITESM campuses. Many ITESM students also had Internet access from home.

Students registered with UBC are required to have Internet access and a machine capable of running Netscape 3.1. We expect students to know how to operate their machines and access the Internet before they start the course. Generally, UBC found few of its registered students had major problems using the technology. Opening attachments (e.g., assignments attached to e-mails) was the major difficulty for both students and tutors because of the lack of standardization, but it was more of a nuisance, especially with collaborative assignments, than a major obstacle. We were surprised that our international students did not have more problems with the technology. However, to some extent, it is a self-selecting group of students; those with no or poor Internet access are unlikely to enrol. The relatively low completion rate for the Venezuelan students was partly caused by the fact that many students have problems with English, but mainly it was caused by technical problems at some of the campuses.Some servers were often down and access speeds were slow because there is only one limited capacity Internet line out of Venezuela.

The major problem we had with technology, though, was with the printed material. Because of the short turnaround period, we had major problems getting the required texts from the publishers in time to distribute to students, particularly internationally. One publisher delivered only half an order and never delivered the other half. Another publisher took over four months to deliver. Materials were sometimes held up at customs. Consequently, some students were more than half way through the first course before they received their printed materials.

This problem also affects course design. We need to decide on required books and printed readings a minimum of five months before the course opens, yet our design period is usually less than that. It means that we find ourselves selecting books and articles that are not so relevant as we had expected, and we cannot easily introduce additional print materials that we discover during the design process. For courses in a rapidly developing subject area and for the increasing requirement to respond quickly to the needs of partners or external clients, this is a major drawback of using print.

From the beginning, it was the intention at UBC that these courses should be self-financing. There is a fund allocated from the university’s general purpose operating grant to support the development of distance education courses, but the policy at UBC is to use this money primarily for undergraduate credit courses. From the beginning, the courses on technology-based distributed learning were seen as professional development courses, and, therefore, costs had to be fully recovered.

In the negotiations between ITESM and UBC, UBC made it clear that it expected a financial contribution from ITESM for the development of the courses. An agreement was reached easily and quickly. ITESM pays half the development costs of each course and in return has sole rights to offer the courses in Latin America. UBC has the rights for the rest of the world. UBC is responsible for developing the content and the design of the courses in consultation with ITESM. ITESM enrols and registers students and keeps its own fees. UBC does the same for students outside Latin America. ITESM students get the courses as part of their regular master’s or doctorate program and therefore pay the standard fee. The same applies to the UBC master’s students, who pay a flat annual fee and may choose these courses as part of their program. The DE&T unit then receives $465 per master’s student per course from central funds. For the certificate students, we set a fee of $695 per student per course (a total of C$3,475, or just under US$2,500, for the whole program). We arrived at this figure on the basis of the average cost of our on-campus, face-to-face certificate programs. With the contribution from ITESM towards the development of each course, UBC needs to enrol about 10 master’s students and 30 certificate students to break even. For the course with the CD-ROM, we needed about 10 master’s students and 40 certificate students to break even.

A full cost-benefit study has been conducted on the first UBC course offering as part of the national NCE-Telelearning project. Preliminary results indicate that these courses will make a net profit. However, the development costs of the first course were 70% higher than originally budgeted, mainly in the areas of course administration and tutoring rather than course development. However, actual costs appear to be much closer to budgeted costs for the second course because many of the administrative and tutoring issues have been resolved.

Although it would be an exaggeration to say that online technology is not a problem, it was minor compared with some of the other issues we have had to address. Applying the KISS principle seems to have worked in the context of this program. Using simple, cheap, widely available, well-tested technology, such as Netscape, HTML, and Hypernews, enabled us to provide a reasonably accessible, reliable, and acceptably fast online service, even over international public networks. Where we needed more complex graphics and software, CD-ROM design and distribution has served us well.

The most problematic area has been the curriculum or rather the wide range of students we are trying to serve with the same core material. We are still awaiting the formal evaluation report on the first course, but already a major issue has been identified.

We found no academic difference between the UBC master’s students, the Canadian or international certificate students, and the Mexican students who participated in the UBC discussion groups and collaborative assignments and most of the other students. However, there was a big difference in terms of criticism of the teaching approach adopted in the first course between some of the UBC master’s students and the rest of the students. This problem was also reflected in a tension between UBC faculty on the Academic Approval Committee and the course developers over the teaching approach in this program. The argument can be somewhat oversimplified as a tension along the following lines: theory versus practice; critical perspectives versus skills and knowledge; academic versus applied.

The course developers have tried to cover all these aspects, but different parts of the program have a stronger emphasis on one rather than the other. The battle is being fought over the revision of the first course, “Designing, Developing, and Delivering Technology-based Distributed Learning.” The criticism is that the approach in the first two courses is still too functional and logical-technical. The faculty would like us to take a much stronger deconstructionist approach, raising questions such as: Who is setting the agenda for promoting technology-based teaching? What are the implicit value systems that support technology-based teaching? What are the negative social effects of distance education and technology-based learning?

Although the course developers recognize the importance of this approach, they feel that it is addressed to some extent in the first course but that the major emphasis on these issues will come in the fourth course, “Social and Policy Issues” (which has not yet been developed). Second, many of the certificate students (18 out of 30 in the first course and 31 out of 52 in the second course) already have a master’s or doctorate in education. Thus, a good proportion of our students are already likely to have been exposed to a deconstructionist approach. The course developers believe that there is a need for practitioners to deal with “logical-technical” issues, such as technology selection and use, budgeting and cost analysis, and planning and management, while at the same time recognizing that decisions will be influenced by values and knowing that deeper questions than how to apply a particular technique need to be asked.

Last, there are already other excellent courses that focus almost entirely on a critical perspectives/deconstructionist approach, such as the Master’s in Distance Education at Deakin University. We believe that the unique aspect of this program is its attempt to deal specifically with the technical and technological issues within a critical framework.

The danger for the program is that the course developers’ approach may not be acceptable to the Faculty of Education at large and that it will, therefore, fail to get formal academic approval, which will prevent it from becoming a regular and integrated part of the Master’s in Education program. That, however, is a risk we are willing-indeed we feel we have-to take.

The biggest barriers we had to overcome were organizational and bureaucratic. The formal academic approval process at UBC would have been too cumbersome to permit this initiative if it had been strictly followed. Fortunately, we had strong support from academic staff in the Department of Educational Studies, who demonstrated creativity, flexibility, and skill in moving this program forward while remaining consistent with the formal process of approval. We also had to repeat the process for the approval of the certificate program within our own division of Continuing Studies, and even there we have had to argue vigorously over issues such as overhead charges and duplication of services.

However, academic approval is also a minor issue compared with some of the other administrative and organizational issues that we had to face. There was a whole set of related issues concerning payment from international students, ordering and delivering of print material, and tracking of payments and print orders.

This problem is best explained by taking a student perspective (this is an actual example). Three weeks before the course is due to begin, a student in Serbia sees the information about the course on the Internet and decides to enrol. She has to ask her employer to pay the fee. Once the employer agrees, she then has to get the money changed from Serbian into Canadian currency and then transmitted in some form to UBC’s Continuing Studies. She also has to get a separate payment for the printed material, which she has to order from UBC’s Bookstore by fax. When we started, UBC’s financial services did not accept international electronic funds transfers. The Bookstore was not used to dealing with international orders nor full fee-paying students. Therefore, it would not ship until payment had been received. It also started to send the books by regular mail and did not track the orders. When the Serbian student complained that her materials had not arrived, we could not track whether the order had been sent, was still in the mail, or had been held up at customs (it turned out to be the latter).

We have now set up a one-stop shopping system for students. While there is one course fee, students can choose between a variety of supplementary material delivery options. Once they have made their choice, they make a single payment for both tuition and materials by electronic funds transfer. The Bookstore still orders the books and clears copyright for printed materials on our behalf, but we pack and ship the materials ourselves, often using international courier services, if the students have chosen and paid for that option. We have our own course administrator who handles student registration and fee payments; monitors the ordering, shipping, and tracking of materials; issues passwords; and is the single point of contact with students when they have administrative queries. She is also our primary liaison with UBC Finance, the Registrar’s Office, Faculty of Education administration, and the Continuing Studies Certificate program co-ordinator for all matters related to this program. It is not surprising that in the cost-benefit analysis, we found that the course administrator’s time spent on the first course was 400 hours more than anticipated.

Another unanticipated problem we ran into was over transferability of courses for master’s students between British Columbian universities. There was a general agreement in place between the Deans of Graduate Studies of all the western Canadian universities that a master’s student registered at one university could take a single course from another university without charge. As a result, for the second course we had seven students and an instructor from another university’s master’s program enrol under this agreement. However, since this is a cost-recovery program, we needed the $465 per student to cover the tuition costs. When the director of Budget and Planning at UBC heard about this problem, he immediately withdrew UBC from the Western Deans’ Agreement with regard to distance education programs. The seven students were halfway through the program by this point. Fortunately, the instructor was able to transfer them to a directed studies program status and they still got credit from their own institution, but we ended up teaching them without payment.

The consequences of this situation are quite profound. Under current arrangements, master’s students in British Columbia pay a flat fee of around $2,500 per annum while in the program. By removing distance education from the Western Deans’ agreement, students can still attend face-to-face classes at another institution free of charge, but they would have to pay an additional $695 to take one of our distance education courses. We are therefore trying to change the whole system of payment for both on-campus and distance students in masters’ programs to a cost per course basis, which is both fairer to part-time students and makes transfer between programs financially simple and fair to operate. However, it means getting all the universities in the system to agree to the change.

It is important not to misunderstand the message here. UBC’s administrators are not stupid or incompetent. The systems have been developed for quite different circumstances. We were not able to anticipate in advance what new problems were likely to arise as a result of going into international course delivery on a serious scale. It is actually to the credit of UBC administrators that when presented with a problem and an alternative method of solving the problem, they have been in general more than willing to make the necessary changes.

When going international, the benefits of having a partner organization are immense. ITESM provided Latin American students, financial support, local organization, and academic credibility, feedback, and cultural and language adaptation through their tutoring. UBC provided academic credibility through its experience and content experts and additional international prestige through its global reach.

The formal partnership agreed at the highest level between the two organizations was also very important. It enabled the teams at both institutions to overcome major institutional barriers, and it gave institutional support for a project that had to change well-established practices and procedures in both institutions if it was to succeed. There is a special chemistry about this particular partnership between DE&T and the Virtual University. Working relations between the two teams have been excellent throughout. There has been a lot of consultation (almost entirely by e-mail and video-conferencing), and a genuine feeling of mutual respect in the relationship.

Lastly, given that there are still some major issues to be resolved concerning academic control and financial relationships between the Faculty of Education and Continuing Studies at UBC, an effective working relationship between DE&T and the Department of Educational Studies has also been essential.

We believe that this program has already proven to be successful. We have found high demand for the course, it works technologically, we have attracted students from all around the world, we are receiving good feedback and high satisfaction ratings from most of the students, and the program is almost certainly self-financing.

The program is a good example of a niche market. We have identified a fast growing area of expertise for which there is limited but specific demand on an international scale. Our target group, because of the subject matter, is more likely to have access to the technology and to be skilled and comfortable in using it for their studies. Because most students are already working in a professional area, they have been able to find the money to cover the full costs of the course. Nevertheless, our approach and, in particular, our use of technology will not be appropriate in many other contexts.

International online teaching is also not an enterprise that should be undertaken lightly if a high quality and successful program is to be launched. It needs thoughtful market research, strong institutional support, and adaptability to local needs. Major administrative and bureaucratic obstacles will need to be overcome. Above all, it needs a dedicated and hardworking team with very strong motivation to succeed.

Nevertheless, if these conditions can be met, delivering international programs online can be a most satisfying experience for students and teachers alike.

Dr. A.W. Bates, Director

Distance Education and Technology

Continuing Studies

The University of British Columbia

2329 West Mall

Vancouver, B.C. Canada V6T 1Z4

Tel: 1-604-822-1646

Fax: 1-604-822-0822

E-mail: tony.bates@ubc.ca

Dr. José Gpe. Escamilla de los Santos

Director de Programas en Tecnologia

Educativa

ITESM - Universidad Virtual

Av. Eugenio Garza Sada 2501 sur,

Edificio Cedes, 1er Piso

64849 Monterrey N.L.

MEXICO

Tel. 52-8-328-4466

Fax: 52-8-328-4055

E-mail: jescamil@campus.ruv.itesm.mx