Development of Communication Conventions in Instructional Electronic Chats |

Karen L. Murphy and Mauri P. Collins

VOL. 12, No. 1/2, 153-175

The widespread use of computer conferencing for instructional purposes, both as an adjunct to and a replacement for the traditional classroom, has encouraged teachers and students alike to approach teaching and learning in ways that incorporate collaborative learning and the social construction of knowledge. Discussion and dialogue between instructor and students and among students is a key feature of computer conferencing and the foundation of constructivist learning techniques. Computer conferencing can be used both asynchronously, which allows time for reflection between interactions, and synchronously, which gives opportunities for real-time, interactive chats or open sessions among as many participants as are online simultaneously.

This study used content analysis to identify the communication conventions and protocols that real-time, interactive electronic chat users developed in instructional settings. The study also determined that the students recognized a need to use their communication conventions and protocols to communicate clearly and minimize misunderstandings in their online transactions with others. The most frequently used conventions included sharing information or techniques for conveying meaning and indicating interest in a topic, using keywords and names of individuals, using shorthand abbreviations, questioning and seeking clarification, and establishing social presence by greeting each other and referring to others by name.

L'utilisation répandue de la conférence par ordinateur à des fins d'enseignement, à la fois comme support et comme substitut à la salle de classe traditionnelle, fait en sorte que tant les enseignants que les étudiants ont été encouragés à considérer l'enseignement et l'apprentissage de manière à pouvoir y incorporer l'apprentissage par collaboration ainsi que la construction sociale de la connaissance. La discussion et le dialogue entre l'instructeur et les étudiants de même qu'entre les étudiants est une composante clé de la conférence par ordinateur et constitue l'un des fondements des techniques d'apprentissage constructiviste. La conférence par ordinateur peut être utilisée tant de manière asynchrone, ce qui permet du temps pour la réflexion entre les interactions, que de manière synchrone, ce qui favorise des occasions pour des discussions interactives en temps réel ou des sessions ouvertes entre autant de participants qu'il s'en trouve en-ligne à un même moment.

Cette étude a eu recours à l'analyse de contenu pour identifier les conventions et protocoles de communication que les participants aux discussions interactives électroniques en temps réel ont développé dans des contextes d'apprentissage. Cette étude a également fait ressortir l'idée que les étudiants reconnaissent le besoin d'utiliser leurs conventions et leurs protocoles pour communiquer clairement et ainsi minimiser les malentendus dans leurs transactions en-ligne avec les autres. Les conventions les plus fréquemment utilisées inclues la mise en commun d'information ou de techniques pour partager le sens donné à un sujet ou en indiquer l'intérêt, l'utilisation de mots clés et de noms d'individus, l'utilisation d'abréviations, le questionnement et la recherche de clarification ainsi que l'établissement de la présence sociale en se saluant mutuellement ou en référant aux autres par nom.

The widespread use of computer conferencing for instructional purposes, both as an adjunct to and a replacement for the traditional classroom, has encouraged teachers and students alike to approach teaching and learning in ways that incorporate collaborative learning and the social construction of knowledge. Discussion and dialogue between instructor and students and among students is a key feature of computer conferencing and the foundation of constructivist learning techniques.

Dialogue has been recognized by Moore (1973) and Moore and Kearsley (1996) as a determining factor in the amount of transactional distance that exists in most, if not all, instructional events: those taking place in a traditional classroom and those taking place at a distance where instructor or student may never see one another. Transactional distance describes not only a dimension of a physical separation between instructor and learner but also a communication gap that must be bridged by dialogue in some structured fashion so that shared meaning can be constructed, teaching and learning can occur, and the potential for misunderstanding and miscommunication can be significantly diminished. When teaching at a distance, instructors must use some form of communication technology to carry this critically important dialogue between teacher and student and among students. In electronic venues, this usually takes one of several forms of computer conferencing.

Computer conferencing can be used both asynchronously, which allows time for reflection between postings, and synchronously, allowing real-time, interactive “chats” or open sessions among as many participants as are online simultaneously. There are a number of different forms of synchronous online communication. An electronic chat is a series of real-time, short (usually 1 to 3 lines) text phrases and sentences exchanged with the other participants who are logged onto the same computer system and facility. The interactions appear as individual lines of text, prefixed by the nickname of the contributor, that scroll up the screen as they are entered.

Internet Relay Chat (IRC) is an example of a synchronous communication program that is international in scope and is available to anyone with access to a client program and who can log on to any one of the IRC servers located across the Internet. IRC can involve large international groups of people, many of whom may be strangers. Real-time electronic chat is commonly used for recreation and social interaction. On IRC, both topic and tone of discussion is policed only by the participants, with the result that a shared culture has gradually developed, defining communication norms and conventions somewhat differently than they are in face-to-face conversations.

Synchronous online communication can also occur in “members only” situations like chat rooms on commercial services like CompuServe or America Online, where the topics and language of “appropriate” discourse are defined and policed by the online service provider. Synchronous online communication is also a feature of closed groupware systems, like LotusNotes, FirstClass, and other systems used for computer supported collaborative work in business and education, where the norms of business and academic discourse usually prevail. Users of UNIX and VAX computer systems can communicate privately, one-to-one, using the system facilities called “talk” and “phone” where users type at each other in real time, each in their own half of a horizontally split screen.

Since the late 1980s, computer-supported collaborative work using various groupware programs has supported chats for information exchange, brainstorming, discussion, and problem-solving in business settings (Lloyd, 1994). Increasing interest has developed in the use of chats for instructional purposes through virtual classes, such as those at Athena University and Diversity University, using a highly structured MUD or MOO format. Instructional electronic chats (IECs) can also supplement both traditional face-to-face and distance coursework.

IECs are intriguing to educators because they appear to allow a sense of communicative immediacy and presence that is often lacking in asynchronous computer-mediated communication. Synchronous dialogue, when appropriately structured, can help reduce transactional distance. Questions and concerns can be raised quickly and addressed, and misunderstandings can be sorted out. IECs pose challenges for educators because the verbal and nonverbal communication protocols used in face-to-face or in video-based distance education settings may not be sufficient for quality educational exchange with and among participants. The design of most forms of IRC software is such that multiple disjointed conversational threads can quickly develop as various members of the group form smaller, rapidly changing conversational groups, each focused on its own topic and ignoring or only intermittently joining in others. These threads may result in conversational chaos. Even affective protocols such as emoticons (smilies) used to enhance e-mail communication are not necessarily transferable to an IEC. Day and Batson (1995) note “although at first it may seem difficult to follow the separate strands or topics, classes typically get used to the nonlinear ’flow’ of the conversation rather quickly” (p. 29). They do not say how this “getting used to” occurs, nor how students develop and establish the communication conventions necessary for meaning-making in the turbulent flow of on-screen conversation. This is the problem that has intrigued us.

The current study asked the following questions:

Adult educators frequently use discussion in their teaching to reach one of their primary goals, which is “encouraging adults to undertake intellectually challenging and personal precarious ventures in a non-threatening setting” (Brookfield, 1986, p. 135). Interacting openly with their peers in discussion groups, either face-to-face or in some technologically-mediated fashion, adult learners can practice using the new conceptual tools they are acquiring. Supportive feedback can be immediately forthcoming as they tentatively articulate their changing ideas and opinions, and so can rousing arguments as opposing perspectives clash. Learners can be exposed to widely divergent points of view, lifestyles, and belief systems and can receive encouragement as they enlarge and revise their own worldviews.

When using computer-mediated communication for discussion, teachers and learners use several different kinds of text-based electronic communications modalities. Asynchronous electronic communication in its most familiar form takes place via electronic mail, newsgroups, or computer conferences. A message is composed and then sent, to be read by the recipient(s) at a later time. The parties to the transaction do not need to be online synchronously (i.e., at the same time). Synchronous communication does require that all the parties to the discussion be online and participating at the same time. The familiar name for this activity is “chat,” although the discussion appears as lines of text that scroll up the screen, each input identified by the nickname of the discussant.

The FirstClass(tm) computer conferencing program used for the courses described in this paper has facilities for both asynchronous (electronic mail and postings to class conferences or discussion groups) and synchronous (real-time chat) communication. Students can access the FirstClass server via the Internet at time convenient to themselves and work independently on their projects and assignments, read and respond to their electronic mail, and read and post comments to the various open and closed class conferences, as McIsaac and Ralston (1996) describe. For a scheduled chat session, the participants must all be logged into the FirstClass server at the same time, reading and contributing to the ongoing discussion.

The use of synchronous electronic communications programs in instruction is relatively new. While it has been used in college writing classes (Day & Batson, 1995) and to teach literature (Harris, 1995), the more common use of synchronous chat programs among undergraduate students is to communicate with one another (Archee, 1993; Newby, 1993) for social and recreational purposes (Aoki, 1995) using IRC and similar public synchronous communications programs.

Public IRC is a text-based, international, message-handling program resident on many Internet servers. Multiple communication channels (similar to citizen’s band radio channels) can be created and named (sometimes fancifully) by their creators, thus introducing the meta-message: “Let’s make-believe and suspend disbelief” (Ruedenberg, Danet, & Rosenbaum-Tamari, 1995). Generically, these channels are variously designated as “chatlines” or “chat rooms” and encompass discussion on every conceivable topic. Access via a client program allows users to join and listen in on (read) conversations on multiple channels on multiple servers. With experience, four or five different channels can be attended to at one time (Gizelle, 1996, personal correspondence). Users join the channel(s) of their choice and type in their conversational contributions, one line at a time, and the “conversation” is distributed, via the servers, to all those who are logged on and listening to (reading) that particular channel.

Synchronous communication program users identify others, often strangers, with similar interests and engage in conversations with them. Users of public synchronous chat programs are customarily identified by a descriptive nickname that is sometimes chosen to “promote a certain image or invite a particular response” (Newby, 1993, p. 35). A nickname can serve as a mask not only to hide identity but also to call attention to the person through the expressive power and imaginativeness of the mask (Ruedenberg et al., 1995). Nicknames and other personal information can be changed at will, so that anonymity can be maintained within IRC programs until users choose to reveal their true identities to each other (Reid, 1991), which may never happen (Phillips & Barnes, 1995).

Advantages

Aoki (1995) notes that brainstorming and other activities requiring spontaneity can be handled effectively in a synchronous chat, as can decision-making that requires a quick turnaround time rather than extended discussion (Siemieniuch & Sinclair, 1994).

Synchronous communication can simulate an instructional environment that is familiar to students, faculty, administration, and funding sources (Fanderclai, 1995). Formal behaviour patterns may carry over from the face-to-face classroom, and students may find it easier to orient themselves when surrounded by familiar, albeit virtual, structures like classrooms, libraries, cafés, and faculty offices.

Synchronous communication adds the excitement of interacting with others in real time and builds a sense of social presence (Aoki, 1995)- there really are people on the other side of the computer screen-and a heightened sense of involvement in the ongoing communication events (Ruedenberg et al., 1995). This involvement can lead to what Csikszentmihalyi (1977) refers to as a “flow experience” in which action and awareness are fused, the passing of time is unremarked, and the activity itself becomes intrinsically rewarding and deeply engaging. This sense of involvement and engagement can be critical in building a sense of community among the participants (Reid, 1991).

Limitations

IRC software provides participants with a small window (approximately two lines deep across the screen) in which to type their contributions, which is input in its entirety into the conversation when the “return” or “enter” key is pressed. Only then can the new input be seen by all participants. Turn-taking in synchronous communication is problematical because there are no observable kinesthetic or para-verbal cues to indicate when someone wants to enter the conversation or to change the subject. Siemieniuch and Sinclair (1994) suggest that verbal and nonverbal protocols currently used in face-to-face meetings may be inadequate for synchronous computer-mediated communication and that perhaps some controls must be built into the software to rationalize the passing of conversational control from one participant to another to permit efficient interaction.

Synchronous communication requires substantial typing skills for a participant to communicate effectively, and the conversation may move too fast for non-native speakers of English, who have no time to reflect, frame questions, and compose responses as the text incessantly scrolls up the screen (Aoki, 1995), especially when there are many conversational participants.

Frequent users may have skills that novices have not had time to develop: “users are adept at following multiple chains of discussion at once, reading other’s responses while typing their own. The every-changing flow of messages results in considerable cacophony in the number of simultaneous thought-trains expressed on a channel. The closest analogy in the non-networked world would be a pub or a party” (Newby, 1993, p. 35).

The novelty of being in a virtual classroom will not last through an online lecture that appears as line after line of “teacher-talk,” input at the teacher’s typing speed or ability to cut and paste from a prepared text. Synchronous communications environments are designed for rapid interaction, and students will soon want to DO something (Fanderclai, 1995).

Hiding behind a nickname, habitual “chat” users can develop communication habits that might be disruptive to an instructional setting: Protected by the anonymity of the computer medium, and with few social context cues to indicate “proper” ways to behave, users are able to express and experiment with aspects of their personality that social inhibition would generally encourage them to suppress (Reid, 1991). Users of synchronous communication may choose to change the way they express their personalities; the anonymity and consequent sense of being alone can allow them to switch genders (Reid, 1991) or change their age; a quiet person may become expressive, abusive, or explosive. Participants can enjoy a sense of reduced accountability; actions and utterances are often in a playful mode or can erupt into sudden bursts of conflict (Ruedenberg, et al., 1995) and the vitriolic verbal abuse known as “flaming” (Aycock, 1995).

Curtis (1992) has commented that the technical aspect of text-based synchronous communication has significant effects on social phenomena, leading to new modes of interaction and new cultural phenomena. The lack of actual physical presence, indeed the often great physical distances between individual participants, demands that a new set of behaviour codes be invented if the participants are to make sense of and understand each other (Reid, 1994). In the case of synchronous chat, these are behaviours expressed in text that are designed to present a recognizable self, set a context for the interactions, share affect and meaning, and minimize misunderstanding.

Because synchronous communication users frequently spend many recreational hours chatting with (typing to) each other, communication conventions arise in several forms, including shorthand for common phrases (e.g., btw = by the way; brb = be right back; rotfl = rolling on the floor, laughing).

Ruedenberg et al. (1995) call communication on IRC a “veritable forest of symbols” as participants use typographic symbols “comprised of such humble materials as commas, colons and backslashes” to convey affect, as in the use of the ubiquitous emoticons known as the “smiley” :-) and the “frownie”:-( among many forms. Aycock (1995) notes that these “orthographic pictures” appear to indicate an “impersonal, but friendly” interest.

Conventional text emphasis cues are used to signal conversational tone and nonverbal communication information through underlining, capitalization for emphasis (read as SHOUTING), misspellings for slang purposes, and exclamation points !!! (Kuehn, 1993).

In his discussion of Foucault’s notion of fashioning oneself (souci de soi), Aycock (1995) notes that online discussion participants use at least three textual devices in their “presentation of self” (Goffman, 1959):

In addition, key words and personal names may be used to preface comments. In the ever-scrolling lines of text it is difficult to follow conversational threads, so key words are used as indicators of content or the individual to whom the comments are directed.

Playfulness is indicated by multiple repetitions of phrases or invitations to join a particular channel (Ruedenberg et al., 1995) and textual manipulations signifying jokes, sarcasm, irony, and witticism (Kuehn, 1993). Disclosure of personal information in an otherwise anonymous textual environment allows others to form an accurate perception of personal presence. The more one discloses personal information, the more others are likely to reciprocate, and the more individuals know about each other, the more likely they are to establish trust, seek support, and thus find satisfaction and to create a sense of being in a safe learning/discussion environment. Without disclosure and interaction, nothing happens. Disclosure creates a kind of currency that is often spent to keep interaction moving (Cutler, 1995).

Social presence in cyberspace takes on more of a complexion of reciprocal awareness by others of an individual and the individual’s awareness of others. . . to create a mutual sense of interaction that is essential to the feeling that others are there (Cutler, 1995, p. 18). It can be indicated by referring to others by name and to past, present, or future activities that have occurred in the shared communication space or in real life.

Status in face-to-face interactions is often signified, as it is in face-to-face conversation, by who can interrupt whom and by who can speak to whom, who takes conversational leadership and who listens, and by who changes topics or otherwise directs the group’s activities.

Moore defines a distance education transaction as “an interplay between people who are teachers and learners, in environments that have the special characteristic of being separate from one another, and a consequent set of special teaching and learning behaviors” (Moore & Kearsley, 1996, p. 200). He goes on to say that distance teaching behaviors can be described in terms of two clusters of variables: dialogue and structure. “Dialogue” is defined as a positive interplay of words, actions, and ideas (or a series of such interactions) between teacher and learner(s) that is purposeful, constructive and valued by each party to the transaction and directed to increased understanding by the student. (p. 201). “Structure” is defined as the extent to which an educational program can accommodate or be responsive to each learner’s individual needs. Structure is expressed in the rigidity or flexibility of the course’s educational objectives, teaching strategies, and evaluation methods (p. 203). Dialogue and structure set the parameters of “transactional distance.”

Transactional distance is a continuous, relative variable and describes the “distance” in technologically-mediated educational transactions. This distance is not only a physical measure but also “a distance of understandings and perceptions caused by the geographic distance, that have to be overcome by teachers, learners, and educational organizations if effective, deliberate, planned learning is to occur” (Moore & Kearsley, 1996, p. 200).

Transactional distance is a “psychological and communications space to be crossed, a space of potential misunderstanding between the inputs of instructor and those of the learner” (Moore, 1993, p. 22) and among learners as peers. This transactional distance can be as prevalent and disruptive of learning in a large face-to-face classroom (especially when conducted in a large lecture hall) as it can be when instructional delivery occurs online.

Transactional distance is likely to be at its highest in a recorded television program where there is no dialogue between teacher and student and “where virtually every activity of the instructor and every minute of time provided for and every piece of content [is] predetermined” (Moore & Kearsley, p. 203). In a course delivered using interactive technologies where student and teacher are in frequent communication, transactional distance and the misunderstandings and miscommunications it entails are likely to be low.

Interactive dialogue can permit continuous, structural modifications of course content, pace and activities to suit the learners’ individual needs, and students’ questions and concerns can be addressed immediately, thus significantly reducing transactional distance. By manipulating the communications media, it is possible to increase this dialogue among learners and their teachers and thus reduce transactional distance (Moore, 1993) by reducing the potential for misunderstanding.

The course from which the IEC transcript for this paper was taken was oriented by constructivist learning principles, so communication occurred among students and instructor as conversational peers who learn from and teach one another online as they strive to increase their understanding of one another. To facilitate this understanding, the students developed and used communication conventions to structure their synchronous conversation, reduce the cognitive load, and minimize misunderstandings.

This study involves graduate students studying educational technology and distance education in the College of Education at Texas A&M University during the spring semester of 1997. The students were masters and doctoral students, primarily from education.

The course was delivered by a combination of two-way interactive (compressed) video conferencing (VTel), computer conferencing via FirstClass software, and the Web. The students used the computer conferencing system as both an adjunct and an alternative to class sessions held by video conference. Since 1993, the instructor has used video conferencing and various forms of computer-mediated communication (i.e., e-mail, e-mail distribution lists, VAX-Notes, and computer conferencing via Forum software) to reach her students. These courses are described elsewhere (Murphy, Cathcart, & Kodali, 1997; Murphy Cifuentes, Yakimovicz, Segur, Mahoney, & Kodali, 1996; Murphy, Drabier, & Epps, in press; Yakimovicz & Murphy, 1995).

The instructor was relatively unfamiliar with FirstClass, having used it only since Summer 1996. The pioneer users were faculty and students involved in educational technology courses. Technical support for FirstClass was almost nonexistent. Students enrolled in the course included in this study were required to use FirstClass for two purposes: (a) asynchronous communication through computer conferences, e-mail, document sharing using attached files, and writing in collaborative documents; and (b) synchronous chats. Both asynchronous and synchronous computer conferencing were used for virtual class meetings. Without any protocols other than the netiquette explained by Mason (1991), the students in chats in earlier courses made off-task remarks, used acronyms and other text-based shortcuts, occasionally reprimanded each other, and turned what was intended as an instructional event into conversational chaos. During the previous two semesters of incorporating chats in courses, the instructor experimented with various degrees and forms of structure in the chat sessions, each time requesting reflection afterwards from the students. The students’ reflections on chats in another course were posted in an asynchronous conference. Those students spoke of the need to structure chat time “to make sure we don’t ’trip’ over each other and that things move swiftly along” and “when there is not enough structure there is little accomplished; when there is too much structure the objective could just as well be accomplished asynchronously.”

The course providing the basis for this study was the first course that the instructor ever taught online, in which 12 out of the 15 class meetings were held by a combination of FirstClass asynchronous conferences and synchronous chats, a listserv discussion with another university, a web page (http://disted.tamu.edu/~kmurphy/618index.htm) maintained by one of the students, and a web board (http://disted.tamu.edu/~kmurphy/wwwboard/wwwboard.html) enabling both asynchronous threaded discussions and a real-time chat function. The IEC lasted approximately 90 minutes, was moderated by the instructor, and was open-ended, which allowed the students to raise issues that they considered important. During this IEC (the second chat of the semester, held on February 18, 1997), the instructor and students established the agenda and then brainstormed decisions about their responsibilities for moderating the next listserv discussion topic, how to use the web board, and plans for a lab session on constructing individual web pages.

The research team consisted of the instructor and a graduate student from another university. The instructor had been involved in distance education for over a decade and was experienced in using a variety of forms of computer-mediated communication in both teaching and conducting research. The graduate student was very experienced with moderating listservs and using chat functions to conduct research, and she participated via FirstClass in two of the initial large group chats in previous courses and used the chat function for continuing communication with the instructor. The two researchers collaborated throughout the process of data collection, analysis, writing, and rewriting. We downloaded and printed out the relevant electronic file of messages from the asynchronous conferences and the logs of several chats that were available in the other courses.

The subjects in the IEC under analysis were the students in “Applications of Telecommunications in Education,” a distance education course. This elective course consisted of ten students who were experienced and interested in telecommunications, some of them working as telecommunications professionals. Adding to the complexity of communication were three students whose native language was not English. Five students had taken a previous class involving FirstClass with the instructor and therefore were more experienced with the software than the others.

An examination of the pre-course surveys revealed that nine of the ten students had taken at least one course via distance learning prior to the beginning of this semester and one of the students had taken more than five courses via distance learning. The majority of the students indicated that they preferred to take this course via distance technologies and felt that it would hold their attention well. The students anticipated that they would take more responsibility for their own learning than in more traditional courses and that they would still achieve as much. They expected that active communication and interaction with the instructor and their classmates would be as good as it would be in a traditional class and expected that the course would help them communicate easily with students in other locations.

This research is a case study of one chat in the course “Applications of Telecommunications in Education.” The data sources included: (a) the transcript of an electronic chat, which lasted approximately 90 minutes, (b) transcripts of an asynchronous discussion in a computer conference about IECs, and (c) pre-course surveys.

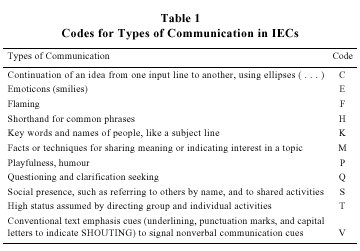

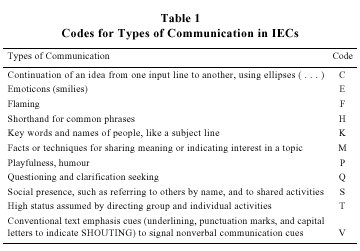

We based our research design on those of other researchers in computer-mediated communication: Henri (1992), Kuehn (1993), and Levin, Kim, and Riel (1990). We used content analysis to examine the data (Krippendorff, 1980). The codes used in our content analysis were derived from the work of researchers in recreational uses of synchronous chats (IRC, MUDs, MOOs) (e.g., Curtis, 1992; Reid, 1991; Reid, 1994; Ruedenberg et al., 1995). Individually, working from the list of communication conventions that we identified from the literature, we read through the transcript of the IEC, seeking to identify the conventions that the students had used. Simultaneously, we sought to identify any other conventions or protocols that the students might have developed. The next step was to compare our coding and reconcile our discrepancies. For example, while reading the transcripts, we highlighted and assigned code words to individual inputs to identify the types of communication that we thought were taking place. (Table 1 lists the codes that we used to identify the types of communication in each unit of analysis, which consisted of a single posting or partial posting in a chat.)

In addition, we established codes to identify quoted messages, which we include in the text precisely as the authors wrote them in the chats, including typing errors. We identify the author of the posting (I = Instructor, and S = Student) and the communication code, which is derived from the list in Table 1. The content analysis consisted of the researchers’ individually coding each entry of the transcript of the chat, then reconciling the differences using Internet Phone. The inter-rater reliability was approximately 85%.

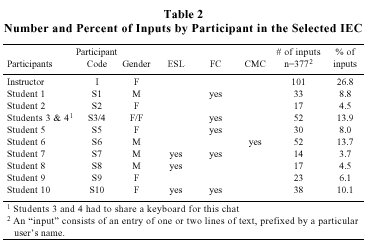

Our first research question asked, “What communication conventions and protocols do IEC users develop?” Table 2 summarizes the number and percentages of postings to the IEC discussed in this paper. In the table heading, ESL indicates that the student is a non-native speaker of English; FC indicates that the student had previously taken a course with this instructor and had used FirstClass; and CMC indicates a student who had taken a previous course with this instructor-a course that included the use of computer-mediated communication, but not the FirstClass conferencing system.

The instructor was responsible for 26.8% of the total inputs (n = 377), and the students posted 73.2% of the inputs. Of the student inputs: 42% were made by males, 58% by females (the gender split in the course was 40% male, 60% female, so the contributions were proportional); 25% were made by ESL speakers, 75% by native English speakers (there were 3 ESL students, so their contribution was slightly less than proportional); 61% were made by those who had taken a course using FirstClass previously (5 students had previously taken a class involving FirstClass and one student was taking two courses concurrently, so the representation was proportionate to course membership).

The participants implemented conventions and protocols that were useful to them as they struggled to make meaning out of this new form of communication. Examples of these communication conventions and protocols are provided with the one- to two-line entries extracted from the IEC, identified by the individual who posted the input. The content analysis of the IEC indicates that the participants used the following conventions, in order of frequency of use in the transcript. The conventions are included below, beginning with the most commonly used ones and ending with those least commonly used.

The students shared facts, helpful hints or techniques to indicate a shared meaning or an interest in the discussion topic:

Many students adopted the convention of typing a keyword or personal name at the beginning of a line to indicate the subject of the entry, or the person to whom the remark was addressed, or whose remark was being responded to:

The students used shorthand as a substitute for common phrases to decrease the amount of typing needed to convey meaning:

Students felt comfortable enough to pose questions and seek clarification of meaning, often from each other:

The students created a sense of social presence, by referring to each other by name, sharing activities, both on- and off-line, and greeting each other:

The participants adopted the use of conventional text emphasis cues (e.g., underlining, punctuation marks, and capital letters that often indicate SHOUTING) to express nonverbal communication:

Evidence of assumption of high status is seen in these postings in which students sought to direct group and individual activities:

The students exhibited their playfulness and humour in attempts to have fun with each other in socially acceptable ways:

The participants used ellipses (. . .) to indicate continuation of a thought from one input line to another:

The instructor occasionally expressed emotion by using emoticons such as smilies:

Table 3 provides a synopsis of the following: the types of communication conventions, who first used the particular convention (student or instructor), and the total use of each communication convention, in order of the most frequently used to least frequently used. The total number of inputs to the chat was 377, which included those made by both students and instructor. The instructor modelled the use of the following five conventions first, and students used them subsequently: K = keywords, H = shorthand, T = status, P = playfulness and humour, and C = continuation of a thought indicated by the use of ellipses. Only one communication convention (E = emoticons and smilies) was used by the instructor and not used subsequently by others. Four conventions that students used first and others used subsequently were: M = shared meaning, Q = questions, S = social presence, and V = nonverbal cues in text. There were no inputs that could be interpreted as flaming in the transcript of this IEC.

A comparison of demographic data from the pre-course surveys with the IEC transcript reveals a positive link between the previous level of use of e-mail and both (a) the frequency of interaction in the IEC, and (b) the number of playful and humorous postings in the IEC. In all, the students developed a repertoire of communication conventions and protocols that they used in this and subsequent IEC.

The second research question asked, “Do IEC users recognize a need to use these communication conventions and protocols to communicate clearly and minimize misunderstandings in their online transactions?” The following remarks, which are extracted from asynchronous FirstClass conferences in the course, reflect the students’ recognition of a need to use a variety of these conventions and protocols to reduce transactional distance.

The students discussed clarity of communication through using keyword descriptors. One student suggested this chat protocol in an asynchronous computer conference prior to the chat analyzed here: “Start every line with a referent: if there are two topics underway, use a title to refer to which topic you are chatting about” (S4, 2-10-97). A second student replied to this posting with the following: “The FC protocol was helpful. I tend to get excited about replying and forget to type in the person I am responding to. Thanks I will try to remember this on the next FC Chat” (S3, 2-11-97). Yet another remarked, “the first chat was not well organized but the second one was improved because of the method of mentioning the name of the students who surpose [sic] to answer or respond to a particular statement” (S8, 2-22-97).

Students used metaphors to create shared meanings with their class-mates, even explaining new words to reduce possible misunderstandings. “Looking back at the chat, my comments seem like you may have created a monster. The proverbial vaccination with the victrola needle. Student 10, are you familiar with the term Victrola? It is a brand of record player. Being vaccinated with a Victrola needle means a person talks a lot” (S6, 2-20-97). Another student’s metaphor related to literature: “To me the synchronous chats are much like Faulkner’s use of stream of consciousness in some of his works. It is analogous to the way one thinks? a flow of information and thoughts. Sometimes mine become waterfalls, but most of the time they move at a slow trickle!? like finding water during a Texas drought” (S5, 2-24-97).

Students, particularly those from other countries, recognized the challenges of the constant and rapid flow of text on their screen during chats. For example, one international student remarked, “Well, chat is never my friend. I cannot keep on with the speed of information coming in. Instead of pitching in at wrong time, I prefer to read and contribute when necessary” (S8, 2-22-97). Another student, without the additional burden of English as a second language, still faced problems with his slow typing speed. He commented, “I had developed some strategies to get around my slow typing speed. I also had an idea of how the process worked so I could tolerate more ’noise’ on the chat” (S6, 2-20-97).

Another technique that students recognized as important in reducing transactional distance was self-disclosure, perhaps from their desire to present themselves on an equal footing to those without excellent telecommunication skills, as the following excerpt suggests.

I would be very interested in learning if others find live chats similar to what I found or if they find them particularly enjoyable . . . I do not like to read large amounts of text. I think therefore, that some of my unease in the first chat was due to personality and preference. (S6, 2-20-97).

Although we did not include self-disclosure as one of the codes for types of communication in our analysis of the IEC, it is clear from the preceding excerpt that students sought to create a sense of personal presence and establish trust in a safe learning environment.

As the semester progressed, the students continued to use various communication conventions and protocols in their efforts to communicate clearly with their peers and the instructor. As they practised with these protocols, the students became more proficient in using IECs for brainstorming and group decision-making-two activities that are handled well in synchronous communication.

Much research on the development and use of communication conventions in computer-mediated communication has been conducted on transcripts of asynchronous conferencing in instructional environments (Harasim, 1990; Henri, 1992; Hiltz, 1994). Research on communication conventions in synchronous computer-mediated communication has occurred in settings such as MOOs and IRCs, which are used primarily for social and recreational activities. Not surprisingly, in this synchronous format most of the research has concentrated on the social aspects of communication, such as play and role-taking (Kuehn, 1993; Ruedenberg et al., 1995). The literature on real-time, computer-based communication in instructional settings is sparse, concentrating primarily on MOOs in which scholarly collaboration occurs (Curtis, 1993; Day, Crump, & Rickly, 1996; Fanderclai, 1995), college writing classes (Day & Batson, 1995) and literature classes (Harris, 1995), and forms of exploratory MUDs for primary and secondary students (Woodruff, 1995).

This study first explored the existing literature to identify the communication conventions and protocols that occurred in synchronous chats, matched them against those developed by the students, then ranked the conventions in terms of their frequency of use in one IEC. While the findings are similar to the literature about communication conventions in non-instructional computer-based chat settings, the purpose of IECs in this study was different: the students were engaged in problem-solving and decision-making, which was usually accomplished through discussion and brainstorming. The students demonstrated their developing competencies in communicating with each other and with the instructor during the second large group chat of the semester. It should also be noted that the students in this course typically checked to see if any of their classmates, or their instructor, were logged on when they were, with the result that they engaged in numerous spontaneous small group chats. Such chats helped the students to improve their skills in a non-threatening setting as well as to enhance their communication with the individuals involved in the chats. These private chats were not saved unless the individuals involved chose to log them.

The study also indicated that the students recognized a need to use their communication conventions and protocols to communicate clearly and minimize misunderstandings in their online transactions with others. Because the class met only three times face-to-face or by video conference during the semester, the regular chat sessions supplemented the ongoing asynchronous communication by providing a simulated face-to-face experience during what would have been regular class meeting times.

Because the course required the students to work collaboratively in small and large group endeavours throughout the semester, the chats in FirstClass provided regular opportunities for the students to ask questions, establish work schedules, make decisions, and stay in touch with their classmates and with the instructor. The students’ metacognitive comments in the asynchronous conferences reflected their confusion when trying to follow multiple chains of discussion at once. Chats were particularly difficult for the slow typists and non-native speakers of English. At the same time, these metacognitive comments reflect the students’ growing skill in sharing facts or techniques to indicate interest in the topic of the conversation, keywords and names of individuals, shorthand techniques, asking questions and seeking clarification, and ways to establish their social presence, such as greeting each other and referring to others by name.

Students were provided with little training or direction in the use of communication conventions and protocols prior to using chats in FirstClass, so the protocols that they developed were based on their prior experience in similar communicative settings (e-mail, classrooms, and face-to-face communication), and the instructor’s modelling of several of the conventions.

Consistent with findings of other research (Rohfeld & Hiemstra, 1995), the students acknowledged that the IECs would have been less productive and more difficult without having first established rapport with the other group members in a face-to-face setting. Additionally, as Hillman, Willis, and Gunawardena (1994) suggest, it is imperative to determine how best to help students in advance to be competent with the technology, in this case the chat process, since they typically did not have the experience of working in a synchronous computer communication setting. Pairing students with keyboard partners of unequal ability in the FirstClass training session appeared to decrease the cognitive load created by having to pay simultaneous attention to content and a new technological process.

When asked to debrief IECs online, students in another course made such observations as “you can interrupt without interrupting,” “I feel I’m in another world,” “you can’t send too much content in a chat,” “a moderator is needed in a chat involving more than 2 people,” “good for visual learners and field dependent learners,” and “Hey, can we get back on video and hash this out? I find chats very frustrating” (excerpted from the third large group chat in the first semester of using FirstClass, 7-24-96).

Further research on IECs needs to include content analyses of chats logged at different times during the semester, chats that focus on specific tasks and topics, and chats in various discipline to determine if the conventions and protocols remain constant and useful over varied times and settings.

Additionally, the categories for content analysis should be refined to include the category of self-disclosure that we did not include in the current study and other categories as they emerge. Further investigation could determine optimal pedagogical techniques that can be employed effectively in IECs of different kinds. Because of the growing global community fostered in the computer-mediated communication environment, it would also seem important to determine ways to empower non-native speakers of English with the conventions and protocols necessary to communicate easily in IECs.

Finally, the growing acceptance and use of instruction grounded in constructivism implies that instructors and teachers need to know more about how to facilitate IECs that foster communication and learning in such settings. Gunawardena, Anderson, and Lowe (1996) developed a model for constructivist interaction analysis of asynchronous computer conferencing, and this model should be tested in a synchronous chat environment.

Karen L. Murphy

Texas A&M University

Dept. of Educational Curriculum & Instruction

308 Harrington Tower, MS 4232

College Station, TX 77843-4232

Voice: 409-845-0987

Fax: 409-845-9663

E-mail: kmurphy@tamu.edu

Mauri P. Collins

Northern Arizona University

The Institute for Learning and Technology (TILT)

NAU BOX 5751

Flagstaff, AZ 86011-5751

Voice: 520-523-4059

Fax: 520-523-0057

E-mail: mauri.collins@nau.edu

Aoki, K. (1995). Synchronous multi-user textual communication in international tele-collaboration. Electronic Journal of Communication (EJC/REC) [Online], 5(4). Available Internet: http://www.cios.org/getfile\AOKI_V5N495

Archee, R. (1993). Using computer mediated communication in an educational context? Educational outcomes and pedagogical lessons of computer conferencing. Electronic Journal of Communication (EJC/REC) [Online], 3(2). Available Internet: http://www.cios.org/getfile\ARCHEE_V3N293

Aycock, A. (1995). “ Technologies of the self “: Foucault and internet discourse. Journal of Computer-mediated Communication [Online], 1(2). Available Internet: http://jcmc.huji.ac.il/vol1/issue2/aycock.html

Brookfield, S. D. (1986). Understanding and facilitating adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1977). Beyond boredom and anxiety. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Curtis, P. (1992). Mudding: Social phenomena in text-based virtual realities. Intertek [Online], 3(3). Available FTP: ftp://parcftp.xerox.com/pub/MOO/papers/DIAC92.txt

Cutler, R. H. (1995). Distributed presence and community in cyberspace. Interpersonal Communication and Technology: A Journal for the 21st Century [Online], 1(2). Available Internet: http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~ipct-j/1995/n2/cutler.txt

Day, M., & Batson, T. (1995). The networked-based writing classroom. In Z. L. Berge & M. P. Collins (Eds.), Computer-mediated communication and the online classroom in higher education (pp. 25-46). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Day, M., Crump, E., & Rickly, R. (1996). Creating a virtual academic community: Scholarship and community in wide-area multiple-user synchronous discussions. In T. M. Harrison & T. Stephen (Eds.), Computer networking and scholarly communication in the twenty-first-century university (pp. 291-311). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Fanderclai, T. L (1995). MUDs in education: New environments, new pedagogies [Online]. SenseMedia Homepage. Available Internet: http://lucien.sims.berkeley.edu/MOO/muds-in-education.html

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Doubleday.

Gunawardena, C. N., Anderson, T., & Lowe, C. A. (1996, April). Interaction analysis of a global online debate and the development of a constructivist interaction analysis model for computer conferencing. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the American Educational Research Association, New York.

Harasim, L. M. (Ed.). (1990). Online education: Perspectives on a new environment. New York: Praeger.

Harris, L. D. (1995). Dante in MOO space: Using networked virtual reality to teach literature. Electronic Journal of Communication (EJC/REC) [Online], 5 (4), np. Available Internet: http://www.cios.org/getfile\HARRIS_V5N495

Henri, F. (1992). Computer conferencing and content analysis. In A. R. Kaye (Ed.), Collaborative learning through computer conferencing: The Najaden papers (pp. 117-136). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Hillman, D. C. A., Willis, D. J., & Gunawardena, C. N. (1994). Learner-interface interaction in distance education: An extension of contemporary models and strategies for practitioners. The American Journal of Distance Education, 8(2), 30-42.

Hiltz, S. R. (1994). The virtual classroom: Learning without limits via computer networks. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Krippendorff, K. (1980). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Kuehn, S. A. (1993). Communication interaction on a BBS: A content analysis. Interpersonal Communication and Technology: A Journal for the 21st Century [Online] 1(2). Available Internet: nhttp://www2.nau.edu/~ipct-j/1993/n2/kuehn.txt

Levin, J. A., Kim, H., & Riel, M. M. (1990). Analyzing instructional interactions on electronic message networks. In L. Harasim (Ed.), Online education: Perspectives on a new environment (pp. 185-213). New York: Praeger.

Lloyd, P. (1994). Groupware in the 21st Century. London: Adamantine Press.

Mason, R. (1991). Moderating educational computer conferencing. [Online]. DEOSNEWS, 1(19). (Archived as DEOSNEWS 91-00011 on LISTSERV@PSUVM.PSU.EDU)

McIsaac, M. S., & Ralston, K. D. (1996, November/December). Teaching at a distance using computer conferencing. TechTrends, 41, 48-53.

Moore, M. G. (1973). Towards a theory of independent learning and teaching. Journal of Higher Education, 44, 661-679.

Moore, M. G. (1993). Theory of transactional distance. In D. Keegan (Ed.), Theoretical principles of distance education. London: Routledge.

Moore, M. G., & Kearsley, G. (1996). Distance education: A systems view. New York: Wadsworth.

Murphy, K. L., Cathcart, S., & Kodali, S. (1997, January/February). Integrating distance education technologies in a graduate course. TechTrends [Online], 42, 24-28. Available Internet: http://disted.tamu.edu/~kmurphy/techtrd2.htm

Murphy, K. L., Cifuentes, L., Yakimovicz, A. D., Segur, R., Mahoney, S. E., & Kodali, S. (1996). Students assume the mantle of moderating computer conferences: A case study. The American Journal of Distance Education, 10(3), 20-36.

Murphy, K. L., Drabier, R., & Epps, M. L. (in press). A constructivist look at interaction and collaboration via computer conferencing. International Journal of Educational Telecommunications, 4(2/3).

Newby, G. B. (1993). The maturation of norms for computer-mediated communi-cation. Internet Research, 3(4), 30-38.

Phillips, G. M., & Barnes, S. (1995). Is your epal an ax-murderer? Interpersonal Communication and Technology: A Journal for the 21st Century [Online], 3(4), 12-41. Available Internet: http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~ipct-j/1995/n4/gmp1.txt

Reid, E. M. (1991). Electropolis: Communication and community on internet relay chat [Online] . Honors Thesis, University of Melbourne, Australia. Available Internet: http://troll.elec.uow.edu.au/~neut/electrop.html

Reid, E. M. (1994). Cultural formations in text-based virtual realities [Online]. MA Thesis, University of Melbourne. Available Internet: http://www.ee.mu.oz.au/papers/emr/cult-form.html

Rohfeld, R. W., & Hiemstra, R. (1995). Moderating discussions in the electronic classroom. In Z. L. Berge & M. P. Collins. (Eds.), Computer-mediated communication and the online classroom: Distance Education (pp. 91-104). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Ruedenberg, L., Danet, B., & Rosenbaum-Tamari, Y. (1995). Virtual virtuosos: Play and performance at the computer keyboard. Electronic Journal of Communication (EJC/REC), [Online], 4(4). Available Internet: http://www.cios.org/getfile\RUEDEN_V5N495

Siemieniuch, C., & Sinclair, M. (1994). Concurrent engineering: People, organisations and technology or CSCW in manufacturing. In. P. Lloyd (Ed.), Groupware in the 21st century. London: Adamantine Press.

Woodruff, M. (1995). Multi-user dungeons enter a new dimension: Applying recreational practices for educational goals. Electronic Journal of Com-munication (EJC/REC) [Online], 5(4). Available Internet: http://www.cios.org/getfile\WOODRUFF_V5N495

Yakimovicz, A. D., & Murphy, K. L. (1995). Constructivism and collaboration on the internet: Case study of a graduate class. Computers and Education, 24(3), 203-209.

Karen L. Murphy is an Assistant Professor in Educational Curriculum and Instruction, Texas A&M University, where she teaches at a distance, combining compressed video, computer conferencing, and the Internet. Her teaching and research focus on distance education, particularly computer-mediated communication, design of online instruction, and sociocultural context of distance education.

Mauri P. Collins is a Research Associate and Adjunct Assistant Professor, Educational Systems Programming, Northern Arizona University. Her interests include web-based course design and the use of interactive communications technologies in distance education. She chaired the first and second annual NAU/Web conferences in 1997 and 1998 and is the conference manager for NAU’s virtual conference centre.