A University Dance Course in Cyberspace:

|

Iris Garland and Lisa Marie Naugle

VOL. 12, No. 1/2, 257-269

Dancing in Cyberspace: Creating with the Virtual Body is a pilot university dance course that explores a new concept of teaching aspects of dance through the medium of telelearning via the World Wide Web (Simon Fraser University, 1996). This totally online course was offered for the first time between January 6 and April 4, 1997 through the Virtual-U at Simon Fraser University by the School for the Contemporary Arts and the Centre for Distance Education, Continuing Studies. The class members were regularly enrolled students at Simon Fraser University and distance non-credit participants from elsewhere in Canada, the U.S., Spain, and France. This paper provides the course organization, examples of class materials as they appeared on the Web pages, methodologies of the Virtual-U, reactions from students and instructors to the online environment, and speculation about the future potential of the place of the Internet in dance education.

Dancing in Cyberspace : Creating with the Virtual Body est un cours-pilote de danse de niveau universitaire qui explore un nouveau concept d'enseigne-ment d'aspects de la danse selon une méthode de télé-apprentissage conçue pour le Web. Ce cours entièrement offert en-ligne, fut lancé pour la première fois entre le 6 janvier et le 4 avril 1997 par l'École des arts contemporains et le module d'Éducation permanente du Centre d'éducation à distance sous l'égide de l'Université Virtuelle à l'Université Simon Fraser. Les étudiants participants étaient des étudiants réguliers inscrits à l'Université Simon Fraser de même que des étudiants à distance d'ailleurs au Canada, des États-Unis, de l'Espagne et de la France inscrits à titre d'auditeurs. Cet article rend compte de l'organisation du cours, d'exemples de matériels de classe tel qu'ils apparaissaient sur les pages Web, de méthodologies utilisées par l'Université Virtuelle, de réactions d'étudiants et d'instructeurs face à l'environnement en-ligne ainsi que de spéculations quant au potentiel éventuel de la place d'Internet dans l'enseignement de la danse.

Technological innovation has a direct influence on dance and art-making behaviour. Art-making behaviour may be construed as ideas being carried out in real-world projects. The effectiveness of dance education online to support art-making behaviour is a challenging new frontier waiting to be crossed. It is not difficult to identify works of art, especially since the Industrial Revolution, that have been extended, distorted, and manipulated in various ways through the use of tools and machines. So the machine aesthetic applied to dance is not new. But the current applications, such as creating dances with 3-D software and distributing them across networked systems of communication, are new.

Dance sites are springing up on the Internet that give access to various kinds of information and interactive possibilities. A logical next step is the exploration of the potential for cyberspace in the field of dance education.

There are cultural critics of the new technologies who have characterized “cyberists” as people who are attempting to liberate themselves from the confines and limitations of the human body, and who are thereby reinventing the mind-body split (cited in Slouka, 1995, p. 71). Perhaps John Perry Barlow has stated this reaction most succinctly: “Nothing could be more disembodied than cyberspace” (cited in Slouka, 1995, p. 39). As dance practitioners, our physical bodies are the medium of our artistic endeavours, and computer technology seems antithetical to our processes and objectives.

Its applications to the human body can only simulate and artificially approximate a phenomenon that is meant to be experienced through the lived body (Fraleigh, 1987, p. xvi). This is the conundrum we confronted in attempting to find an interface between dance and cyberspace.

The opportunity to design and implement an online course at Simon Fraser University came about by the confluence of two factors:

1. Simon Fraser University’s Telelearning Network of Centres of Excellence received a substantial federal government grant, which made technological and financial support available to faculty for designing online courses for the Virtual-U. The Virtual-U, developed at Simon Fraser University (1996), is an

online learning environment. . . . At the heart of Virtual-U is a World Wide Web software tool for group collaboration over networks. The Virtual-U Toolset includes tools for course design and facilitation, class discussion and presentation, course resource handling, and class management and evaluation.

Students may navigate through campus spaces to attend virtual classes, engage in group discussions, view hypermedia course materials, work on assignments, collect information from various online sources. . . . Because Virtual-U is a web-based system, navigation and tool access is accomplished by clicking on hyperlinks embedded in web documents. (p. 3)

2. Life Forms, a computer software 3-D human figure animation tool developed in the Graphics Lab at Simon Fraser University, has been utilized since the middle 1980s by professional choreographers (e.g., Merce Cunningham), dance educators, and dancers internationally. In the dance technology field, Life Forms is gaining recognition in other university dance programs around the world. However, the SFU Dance Program did not incorporate Life Forms into its current curriculum, and our students’ exposure to this dance technology, which was developed at our own university, had been ad hoc. The few dance students who had experience with the Life Forms program had obtained employment based on their expertise. A means to make the technology a formal offering in the dance curriculum was needed. The Virtual-U, with its 24-hour classroom available to students at any time that suited their individual time preferences, seemed an ideal way to introduce the new course without causing scheduling problems with other course requirements and electives.

The proposal for a special topics course, Dancing in Cyberspace: Creating with the Virtual Body, was accepted as the first offering in the School for the Contemporary Arts for the Virtual-U, and a course development team with telelearning and multimedia expertise was established by the Centre for Distance Education to assist with the course design and implementation.

Virtual-U and Life Forms software support learning while the student is doing tasks. For example, online conferences can be used to facilitate the way students gather information, store it for later use, and retrieve it as they are doing new work. As an example, students may work in groups of three to develop a movement animation. They can send, receive, and save movement sequences made by their team members; rework the sequences into a new variations; and retrieve the sequences for later use. The combination of Virtual-U and Life Forms software engages the student in assignments, discussions, and group projects. The online environment has the potential to include participants from all parts of the world, which makes the acquisition of specialized knowledge more accessible.

The course Dancing in Cyberspace: Creating with the Virtual Body incorporated existing dance technology with a new methodology for learning.

An introduction to the virtual body in cyberspace and its creative potential, Life Forms, a 3-D human animation software program, will be utilized to explore human movement through experientially designed sequences. Aesthetic and socio-technological issues of human body representation will be addressed.

The course aims to:

This course is designed to utilize methodology inherent in the unique features of the Virtual-U, which is a substantially different learning environment from that of the traditional classroom, laboratory, or dance studio. Course content that is appropriate for online learning must be selected. For example, teaching dance technique or physical skill acquisition would be inappropriate in a totally online course, whereas content that lends itself to collaborative problem solving, feedback from instructor and peers, and discourse about issues and concepts could benefit from a network approach. However, it is likely that every type of course might benefit from an online component that enables exchange of insights and information. Access through hypertext to the network makes available resources on the World Wide Web, including online databases, libraries, dance sites, and archives (Harasim et al., 1995). The methodology available in the Virtual-U opens new paths of learning experiences while closing more familiar avenues. The Virtual-U software utilized in our course includes the following features.

Electure is the Virtual-U equivalent to a lecture or oral presentation given by the instructor or a student. The computer environment is not conducive to the traditional 50-minute classroom lecture, which would take up several pages of text. Text-based electures are limited to a page and a half maximum on the computer screen. Information must be pared down to its essence and stimulate class member response. As part of the electure, provocative questions are posed for class member response in a conference, and relevant reading references are assigned. References may be in the form of photocopies of articles or book excerpts (with copyright permission) that are mailed to the class members in a reading packet at the beginning of the term.

A conference is a discourse environment based on messaging. Participants in a conference create messages, post them to the conference, and read posted messages. . . . [It is] a collection of messages. (Simon Fraser University, n.d., pp. 7, 9)

Class member responses to electures are limited to one page on the computer screen posted to a conference, and they are opened and read by the instructor and other class members. Strict deadlines are set for the posting of initial responses to electures by all class members. After initial class responses to the topic have been posted and read, class members are expected to post a minimum of two additional responses to the arguments generated by their peers. A lively interchange of ideas is facilitated, and class members develop skills articulating their ideas concisely and clearly. Messages may be reopened after they are marked as read for review by the instructor and class members. A number of different conferences or sub-conferences may be created, either by topic or course design.

The role of the instructor in the telelearning model is that of facilitator rather than lecturer. The learning is “student-centred” inasmuch as the instructor, after creating the framework for the course and guiding the initial sessions, assumes a background role. “The instructor observes, monitors, facilitates, clarifies, summarizes, and provides information” (Simon Fraser University, n.d., p. 8). This learning strategy implies that the collective wisdom of the class exceeds the knowledge of a single expert. Although this model of instructor as facilitator is not new to educators, it is challenging to adapt it as the single methodology for all aspects of course content. Two conferences were created for our course.

In the Topics conference, class members posted their responses to the electures or presentations by the course supervisor/tutor-marker, followed by responses to other class member presentations on the topic. Topics included:

The purpose of the Topic assignments is to encourage the class members to think critically about their online learning environment and generate a discourse about the aesthetic and socio-technological issues of human body representation in cyberspace, particularly in the Life Forms software program.

The Animate conference fulfilled the following course functions:

Class members had a hands-on experience working with the Macintosh 2.0 version of the Life Forms software program. The Life Forms program was installed in all the campus computer labs and program diskettes were included in course materials mailed to distance class members and on-site students with access to home computers. A series of progressively designed exercises was assigned to enable students to learn and gain facility using the Life Forms program. The exercises are similar to short dance composition assignments and resulted in animations that were posted to the instructors and other class members for viewing.

Collaborative assignments are an important part of the telelearning methodology, and in the fourth week, class members began collaborating by adding to their partner’s animation and critiquing the animations of class members.

The completed animation documents were posted as “Attached Documents” via E-mail to the instructors and other class members with home computers. One serious, but not insurmountable, problem in the course design occurred when we discovered during the first week of the course that the SFU computer labs had disabled the “Attach Document” function on the campus computers available to students. The problem was solved by creating a “Drop Box” in all the lab computers to which students could drag their completed animation documents. They were then retrieved and posted to the instructors by a member of our technical team. Likewise, a “Share Box” was created so class members could retrieve and view the animations of other class members. Distance class members were able to send their animations via E-mail to each other and to the instructor. Some distance students had trouble at first with the Attach Document function, but with help from the technical team, and patience and perseverance on the part of the class members, this problem was eventually solved.

E-mail was useful in communicating privately to individual class members. E-mail, or the telephone, was the preferred mode of com-municating concerns about student progress, late assignments, or lack of participation in the conferences. The tutor-marker held weekly office hours for students on campus.

Other conferences on the Virtual-U available to students were:

The Help conference is essential for class members to get assistance from the Centre for Distance Education with technical problems, such as logging on, passwords, and general system computer and software problems that hindered access to the Virtual-U. Technical expertise delivered promptly alleviates frustration and stress. The instructor and tutor-marker also received assistance with their technical problems.

The Café conference is the equivalent to a coffee break. It provides an opportunity for class members to socialize as normal students would do in a face-to-face class situation. Class members initially posted messages to introduce themselves in this conference. The messages are not concerned with course content and are not meant to be monitored by the instructors. The Café serves as a safety valve that allows students to vent frustrations, express humour, and share experiences. It is an attempt to prevent the isolation and possible alienation of learning online by providing a more casual and personal exchange between class members. Ironically, the Café was dominated almost exclusively by a few of the regularly enrolled students on campus. After the introductions, the distance class members, who were for the most part mature professionals, did not participate in the Café.

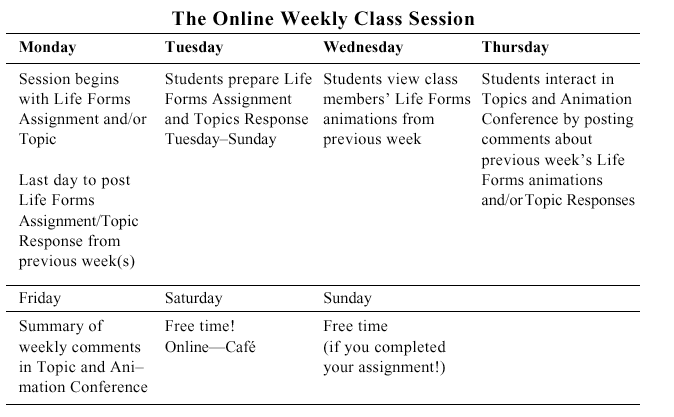

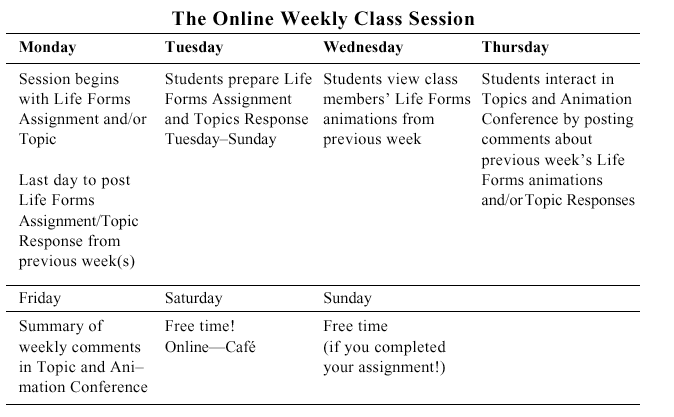

The telelearning pedagogical strategy includes strict deadlines for posting course assignments and conference messages to class members on the assigned topic. An Online Weekly Class Session Table describes the general course activities and expectations for students:

Class members were expected to log on to the Virtual-U three times a week for 30 minutes each time for reading and posting class messages. The instructor and tutor-marker were expected to log on every day and respond to student questions within 24 hours. Work on the Life Forms animations, assigned reading, and composing responses to the Electures occurred off-line.

Class members were mailed the following course materials at the beginning of term to facilitate their learning:

The course was opened to 10 distance non-credit class members, who included graduate students in dance, professional choreographers, university dance professors, a music and computer instructor, and a music student. These distance class members were from various parts of the world- California, Hawaii, Pennsylvania, Madrid (Spain), Valencia (Spain), Lyon (France), and Edmonton (Canada). The University had no administrative procedures in place to facilitate accepting distance students not registered in degree programs at Simon Fraser into online courses. An exception to university policy was approved specifically for this course.

The 22 credit students were largely first- through fourth-year dance students in the B.F.A. Dance Program at Simon Fraser University, but they also included students majoring in theatre, film, and communications. The wide disparity in experience did not seem to be a problem. Everyone was learning the Life Forms software program from scratch, with the exception of two professional choreographers who had experience with the program. Generally speaking, the class members with dance experience created more interesting movement sequences in their animations, but the students in other disciplines did good work, and some excelled, in the Topics assignments. The music/computer instructor experimented with adding music and importing visuals into his last animation assignment.

The design of the Virtual-U was conducive for learning the Life Forms software program. Class members progressed at a faster rate and completed more animations than a previous pilot course taught at Simon Fraser University in a face-to-face situation in the computer lab. T.W. Calvert, the Life Forms Project Leader, has acknowledged that the S.F.U. Graphics Lab has not had much success with teaching the Life Forms software program to individuals in a face-to-face laboratory situation. The credit students, although plagued by numerous technical mishaps in the computer labs (passwords that didn’t work, difficulty in posting animation assignments, download time, etc.), did not drop the course.

One can learn the Life Forms program by reading the Life Forms User Guide , supplied with the software purchase. However, it is a lonely endeavour. The online learning environment creates a community of supportive peers. Collaborative assignments allow class members to work with others in asynchronous time. Critical feedback and shared progressive assignments are incentives for continuous learning over a shorter, more intense time frame.

The students’ work in the face-to-face course contrasts significantly with the online course. The depth of understanding demonstrated in the written assignments and the degree of skills acquired to produce realistic, useful, or complex choreographic sequences were considerably more advanced in the online course. In the online course, all students contributed more than the recommended amount for both written and choreographic assignments. Students in the online course also managed collaborative projects that often involved solving scheduling conflicts because of different geographical locations. Overall, the number of exchanges between students in the online course far exceeded the number of exchanges in the face-to-face course.

The Topics conference provided the biggest surprise for me. Our dance program is studio based with few specialized dance theory courses. Aesthetics and criticism are taught by faculty from other art disciplines, and dance is given little direct emphasis. I was impressed with the dance aesthetic issues that were raised in the Topics conference and the increasingly articulate responses that the credit students made to the ideas generated by other class members and to the readings. I gained a different perspective of my students, most of whom I had taught in other courses. I learned more about their concerns and thinking processes than I did in my face-to-face classes where class participation in discussion is usually limited to several students in the class on any given topic. Only two of the distance class members participated in all of the Topics assignments, but their contributions about the various issues were interesting and provocative. This aspect of the course leads me to believe that other selected dance offerings would be appropriate for online courses.

Dancers who had never used a computer previously made excellent progress in the course. We did not find that dancers objected to creating movement sequences on the computer. They were enthusiastic and interested in technological innovations in dance. Initially, fears were expressed that the human element of live performance would be replaced by simulated computer animations, and much discussion about loss of soul, passion, and expressivity was generated in the Topics conference. Nothing can replace face-to-face interaction, but telelearning can add another dimension, often not expressed in real time and space relationships.

Fifteen of twenty-two credit students and six of ten distance non-credit class members responded to an anonymous student evaluation administered at the end of the course. Four of the ten distance class members did not finish the course. A rating scale was used for various aspects of the course, and individual comments were encouraged.

Rating Scale

(Excellent; Good; Average; Below Average; Very Poor; Useless; n/a)

Selected Items from the Questionnaire

The above average ratings for both the Life Forms and Topics assignments, and the affirmation that the class members would recommend the course to a friend suggest that the course was successful. Nine hundred and seventy messages were posted in the Virtual-U during the semester, exceeding by far the number for other online courses offered simultaneously in the university. This suggests an active and lively participation by the class.

After teaching the face-to-face course in 1996, I could have easily continued teaching in the traditional mode. However, I knew from my experiences of teaching that incorporating a collaborative element increased student enthusiasm for a course and that a Web-based course could reach a greater diversity of students.

On January 6, 1997, we went online for the first time. Endless phone calls and e-mail messages from students on that day and for two weeks to follow made us wonder if we were in cyberspace or Dante’s Inferno. It was a collective challenge from the beginning. The class was online, and, in a sense, we were a new kind of community, but we didn’t have the ease of communication and efficient transfer of information, at least not initially. Meeting students privately for half an hour or hour once during the semester proved extremely beneficial. By mid-semester, most students acknowledged that their choreography, or way of looking at dance, was influenced by the use of Life Forms and being able to have extended conversations with peers online. Some students revealed that they felt less alone in the online class than they did in the dance technique class they shared.

Teaching the course was exciting. It was also extremely labour intensive, more so than any course I have ever taught. Faculty need not fear becoming obsolete with the advent of online learning. As with most technological innovations, it does not save time, nor will the Virtual-U save money for educational institutions.

Teaching dance in virtual spaces is not simply a matter of reproducing images from an original, or conducting a series of action and reactions between people and machines. It may mean we acquire a variety of presentation formats-narratives, images, the ability to navigate, orient, and adapt in virtual environments. Finally, with technological power and precision also comes a need to reconsider policies, copyright, violation of privacy, economic security, and, most importantly, content.

Iris Garland

Professor of Dance

School for the Contemporary Arts

Simon Fraser University

Burnaby, B.C. V5A 1S6

Fax: (604) 291-5907

E-mail: Iris_Garland@sfu.ca

Lisa Marie Naugle

Assistant Professor of Dance and Technology

University of California, Irvine

School of the Arts, Department of Dance

MAB 300

Irvine, California 92697-2775

Fax: (949) 824-4563

E-mail: lnaugle@uci.edu

Credo Multimedia Software Inc. (1996). LifeForms (user guide for Macintosh). Burnaby, BC: Credo Multimedia Software Inc.

Fraleigh, S. F. (1987). Dance and the lived body: A descriptive aesthetics (p. xvi). Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Harasim, L., Teles, L., Hiltz, R., & Turoff, M. (1995). Learning networks: A field guide to teaching and learning online (p. 127). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Garland, I., & Naugle, L. (1997, Spring). Dancing in cyberspace: Creating with the virtual body study guide (p. 2). Burnaby, BC: Simon Fraser University, School for the Contemporary Arts and Centre for Distance Education, Continuing Studies.

Simon Fraser University. (1996, January). Telelearning: “The use of multimedia learning environments based on powerful desktop computers linked by the information highway.” In TeleLearning Research Network (TL-RN) Update (p. 2). Burnaby, BC: Simon Fraser University.

Simon Fraser University. (1996). Virtual-U(tm) workshop manual (p. 3). Burnaby, BC: Simon Fraser University.

Simon Fraser University. (n.d.) Virtual-U: Designing and teaching online courses workbook. Burnaby, BC: Simon Fraser University, CDE Lab.

Slouka, M. (1995). War of the worlds: Cyberspace and the high-tech reality (pp. 39, 71). New York: Harper Collins.

1. This article is based on a paper presented at the Congress on Research in Dance Conference, Art Making Behavior at the University of Arizona, Tucson, November, 1997 and it is printed in their Conference Proceedings. Permission has been granted by the authors to publish in the Journal of Distance Education.

Iris Garland is professor of Dance in the School for the Contemporary Arts and founder of the Dance Program at Simon Fraser University. She is an independent choreographer and teaches dance/movement analysis, Bartenieff fundamentals, dance composition/improvisation, and dance history. Iris is a certified Laban movement analyst.

Lisa Marie Naugle is Assistant Professor of Dance and Technology at University of California, Irvine. She received her MFA from New York University, Tisch School of the Arts in 1992 and is currently working on her Ph.D dissertation, “Collaborative Online Methods in Dance Education.” She has taught at the Julliard School of Performing Arts, New York University, Marymount College, and Simon Fraser University. Lisa has been exploring the artistic uses of LifeForms choreographic software for stage and education since 1989. She initiated the development and co-authored “Dancing in Cyberspace: Creating with the Virtual Body.” As part of her Ph.D research, Lisa is working with several computer-based applications for dance: videoconferencing, web-site performance, interactive performance tools, motion capture, and course development. She currently performs and teaches modern dance technique and composition.

ISSN: 0830-0445