Self-Directed Learning and Distance Education |

This discussion of self-directed learning and distance education begins with aconsideration of the concept of "learning-in- education," and with clarificationof several commonly held assumptions about teaching and learning. Distanceeducation is defined on the basis of these assumptions, and as varying along the two critical factors of structure and dialogue. Self-directed learning isdescribed in some detail in terms of its relevance for adult education. Adults are especially interested in learning that arises from the roles they play as they pass through the stages of human development (i.e., parent, consumer, employee, citizen). Such learning is described as being particularly well-supported by distance teaching, and by a proposed learning advisory network. Implications for teaching in distance education and for the organization of distance learning institutions are discussed. This paper discusses some aspects of the phenomenon called "self-directed learning" and the implications which follow for the curriculum and teaching methods in distance education.

Cette discussion des études auto- dirigées et de l'enseignement à distancecommence par une analyse du concept de la "connaissance par l'instruction" etpar une clarification de plusieurs présomptions courantes au sujet de l'enseignement et de l'apprentissage. L'enseignement a distance est defini selo nces présomptions et selon les variations entre les deux facteurs cruciaux quesont la structure et le dialogue. Une description détaillée des études auto-dirigées et de leur pertinence en ce qui concerne l'éducation des adultes estensuite entreprise. Les adultes sont surtout intéressés par une forme d'appren-tissage émergeant des rôles qu'ils occupent en passant par les divers stages du developpement humain (c'est-à-dire, parent, consommateur, employé, citoyen) . Cette forme d'apprentissage est présentée comme pouvant particulièrement bien convenir à l'enseignement à distance. On propose aussi qu el'enseignement soit appuyé par un réseau consultatif. Les implications pour laforme que prendrait l'enseignement à distance et pour l'organisation des institutions d'enseignement à distance sont discutées.

Cet exposé étudie certains aspects du phénomène et de ses implications pour I'élaboration des programmes et des methodes d'enseignement à distance.

A discussion of the nature of self-directed learning must begin with some consideration of the concept of "learning." There is a common failure to specify the differences in meanings of learning as a psychological construct, in its everyday use, and its special meaning for educationists. As a consequence, it might easily be concluded that self- directed learning is a human activity which is so ubiquitous, so commonplace, that it can not be defined, manipulated, nor studied.

No such confusion and misunderstanding is necessary if an adequate theory of learning-in-education is used as a basis for discussion. Of course there is no such single learning theory generally accepted but there is a r classified as those which view learning as a mechanistic process of response to externally induced stimuli; as a reorganization of cognitive structures; as adjustment of the person in the environment; and as the development of 5 social relationships. In their different ways theories of all these types explain how people learn - that is, how perceptions and behaviours change. as a result of experience. They explain how one learns to stop at a red light, how to behave in a shop in a foreign city, or how to find one s way around the city by bus. Such learning is usually unconscious, and occurs as a result of numerous accidental experiences. It is learning which is not planned. Such everyday, casual and random learning is studied by the psychologist. It is not the domain of the educationist. Ours is a more narrow focus, for our interest is not primarily in understanding how learning occurs - though of course such knowledge is helpful. Our primary interest is in making it happen, in improving it, in planning for it, and in helping it to happen. Our concern is in constructing an environment in which the individual learner, or group of learners, or whole community can learn. A key concept, essential to understanding education, and consequently essential to under standing self-education is intention. Watching a television program, or riding on a bus, or reading a novel, are all likely to result in learning, but as educationists we are interested in such activities only if they were carried out with a deliberate, conscious intent to learn.

It is these characteristics of intent and planning which distinguish the learning we study from that which interests psychologists and others, as for example advertisers, broadcasters and propagandists. "What we are really looking at," says the Canadian, Allen Tough,

. . .is the intention of the activity. So that regardless of what the person isdoing if he is trying to learn, trying to change through that activity, thenwe call it a learning project. People do learn in other ways. There are lots I fof activities that lead to learning. But if that is not the person's primaryintention then we do not include it in our definition of a learningproject. . .I define a learning project as an effort to change. (Tough, 1976, p. 62)

K. H . Lawson of the University of Nottingham makes the distinction between what he calls learning situations and educational situations:

The question 'has he learned X' . . .is concerned only to elicit whether or not has been acquired. The question can however be put with a different emphasis, meaning 'Has he learned x' where learn is given a rather specialmeaning....A learner is someone who wants to achieve something and who is prepared to do something in order to achieve it. (Lawson, 1974, p. 89)

So all the learning situations which educationists are concerned with, even when we talk about self-directed learning, are those in which there is a deliberate goal. If there is a goal there must also be, explicitly stated or implied,7 some criteria of its achievement, and in such planned, goal centred learning, there must be some strategy for reaching the goal . The processes of deciding on the goal, the strategy and criteria for attaining the goal, we call program planning; carrying out the program plan we call implementation; and making decisions about attainment we call evaluation. Together these processes make a learning program:

...a purposeful, deliberate planned activity or series of activities by a learner intended to result in a change in knowledge, behaviour or attitudes. (Moore, 1977, p. 11-12)

Charles Wedemeyer describes the learning program in terms of the different roles played by the learner. He believes that there are seven such roles. The first three are concerned with determining the learning goal, the next three with its implementation, the others are concerned with evaluation:

Role Behanour 1: The learner is passive with respect to learning because he thinks he has learned enough to survive and perceives no new learning needs.

Role Behaviour 2: He is anxious because he thinks or fears that maybe he doesn't know enough, and begins to weigh whether and how he could learn general or specific things that would meet his needs better. His needs are only vaguely perceived but he is beginning to display goal seeking behaviours.

Role Behaviour 3: He casts about for leads that will put him in touch with learning opportunities to satisfy his needs in his situation. His needs are now more sharply perceived, and are being transmuted into learning goals. Anxiety increases, particularly if he fails to locate opportunity that is accessible to him.

Role Behaviour 4: He acts on his goals, makes decisions among the possibilities open to him. He does something to enhance his learning, such as enroll in a learning program or begin one on his own. Whatever overt or covert action is taken to initiate purposeful learning, goals continue to undergo modification. If the action taken is formal, goals are modified according to institutional programs and accessibility. The learner displays learning- or knowledge-seeking behaviors.

Role Behaviour 5: He becomes a student in a specific program. He begins learning.

Role Behaviour 6: He persists (or does not persist) in learning.

Role Behaviour 7: He reaches (or does not reach) his and/or the institution's goals. Anxiety is reduced if successful; increased if unsuc cessful. Further goal modification. (Wedemeyer, 1981, pp. 147- 148)

Educators, like learners, have intentions and role behaviours. Their inten tions are to decide what people might want to learn, or what society might want learned, and to state these wants as teaching goals. They find and organize resources and strategies for achieving their goals, and some way of measuring attainment. Very often, especially in the institutionalized education of young people, role behaviours of the normal learner are overlooked and the processes of learning are taken over by teachers . This is unfortunate, and leads too often to a disrespect for, and rejection of teaching. Education should be an interaction of learning programs and teaching programs. Ideally, a perfect fit should exist between a learner's goals and a teacher's, between the strategies and resources needed by one and offered by the other, and between the criteria of attainment which each finds acceptable.

There cannot be education without some form of teaching. The very word, education in English is derived from Latin "educare," itself related to the verb "educe", meaning "to bring out, to develop from latent or potential existence" (Oxford dictionary). It is a transitive verb, that is somebody must do the educing; at least two persons must be involved in an educational relationship. At some point even the self- directed learner must use help deliberately planned and prepared by another. At that point the learner meets the teacher, and education occurs. In my view, any actions aimed deliberately and primarily to help learning as already defined, may be called teaching. Ministers of religion and librarians are often teachers, but so occasionally are garage mechanics and physicians. Consider, for example, the deliberate, planned, learning and teaching occurring when a nurse instructs a new mother on the care of her first baby, or when a minister visits the family of a dying parent.

What, though, if the young mother or grieving children turn to a library in search of information and advice, or decide to watch a series of television programs on the subject of their concern, or subscribe to the Open University courses on "you and your baby" or "caring for older people"? It is critical for an understanding of self-directed learning to appreciate that teaching (actions aimed deliberately and primarily to help learning) does not have to be personal, individual or face-to-face. The meeting of learner and teacher to which I referred does not have to be a physical meeting, but rather, as the saying goes, a "meeting of minds." In this sense a person can teach by writing a book, producing a radio or television program, or contribute to writing a correspon dence course. With the broadcast media in particular it is not always easy to distinguish a teaching program from one that is entertainment. The same difficulty in the printed medium was recently noted by Jeffcoate (1981), in an on the goals of the book or program, since in an educational program all other goals are secondary to achieving learning. The goal of learning should be clearly intended, and receive first priority - with the content of the program aimed at that goal to the subordination of all others.

So, in education we have deliberate learning and deliberate teaching, and an educational transaction occurs when learning programs and teaching programs are brought together. This meeting might be face to face, with the medium of communication the human voice, or it might be at a distance, conducted across both space and time by print or electronic media. The latter is distance education. The effective ness of distance education is determined by a complex interaction of variables which include learner variables, teacher variables, subject variables, and communication variables. This last set includes variables which may be referred to as dialogue and structure, with a minimum of both in the more distant forms of educational transactions. A teacher who teaches through a communications medium which permits easy and frequent interaction with the learner is less distant than the learner and teacher who communicate through, for example, a one-way medium like the radio. This might be termed the critical variable, "dialogue." The other critical variable is structure. The teacher who prepares a teaching program aimed at only one particular learner is able to tailor, organize, or structure the program to meet the learner's specific needs and interests in a way that is quite impossible if the program is prepared for a million viewers, listeners, or readers.

To me, these two critical factors in combination lie at the heart of all educational transactions . I believe they should be used as the basic concepts for analyzing and organizing distance education. Consider the following possible combinations. If there is dialogue and no structure the teacher can adjust to the learner's intellectual abilities, physical state, cognitive style, and emotional needs. In particular, teaching can be organized according to the learner's own learning program. However, where there is no dialogue and there is a high degree of structure, there can be no negotiation or consultation about program plans; the learner must then follow the teaching program exactly as it is presented.

There is also a third alternative. Learners might be sufficiently confident and competent to design learning programs alone, and draw from a teaching program or several programs only those parts which are appropriate for their goals. It is not uncommon in educational institutions for teachers to plan and prepare programs apart from the learners they expect to use them. It is less common in schools and colleges for learners to prepare learning programs apart from teachers - or indeed to prepare their own learning programs at all.

It is not uncommon for adults, outside educational institutions to plan, implement and evaluate their own learning. This is autonomous, or self-directed learning.

A number of scholars (i.e., Boyd, 1966; Knowles, 1970) have described autonomous learning as especially characteristic of learning in adulthood. Since children tend to have a self-concept of dependence, it is natural for them to look to adults, including teachers, for reassurance, affection and approval. They are usually willing to follow a teaching program, regardless of its congruence with any learning programs of their own, merely to win the 87 approval and affection of the teacher. Adults, on the other hand, have a self concept characterized by independence. In most aspects of their everyday lives they believe themselves capable of self-direction and they are generally capable and willing to be self-directed in their learning also.

Institutional programs of distance education normally have three kinds of adult learner. One kind could be regarded as self-directed learners who have decided that the teaching programs of the institution generally meet their learning goals. It is possible that only part of the program meets a person's goals, and he/she might drop out before the end, might not submit certain assignments, and in other ways might not conform fully with the norms for a "class" or tutorial group. Such persons though, are in the position of customers buying a service; they are well in control of the educational program and should give us no cause for real concern.

Other members of the tutorial group, or other distant learners in a distance education institution, are the learners who are motivated by need for a degree or some other formal accreditation which can only be obtained by following the teaching program offered by the institution. In this case the teaching program might not fit the learning program of the students in the course. Such students are not engaged in an educational program per se, but merely are undergoing the formalities associated with certification. Though not self-directed learners, they are self-directed in pursuit of their non-educational goal.

Finally, there may be students who have neither a learning program, nor need for certification, but who use the educational institution to satisfy an emotional need for dependence. They need affection, reassurance and approval, and have learned in school to win this from their teachers. In schools many teachers fail to assist children in becoming self-directed in learning. As a result it is very common, as Knowles (1970) has pointed out, to leave school adult in other ways, but still dependent, or at least retarded in independence, as a learner.

There is a need for considerable caution in this regard on the part of tutors and counsellors in distance teaching institutions. It is important that the legitimate desire to give emotional support (perhaps we might say "first aid"), to students in distress, does not result in actions that reinforce their dependence. The role of educational councellor or tutor requires that the first priority be to reduce dependence and encourage students to become self-directed. The adult learner

is entitled to do what Boyd refers to in his "psychological definition of adult education," that is to,

...approach subject matter directly without having an adult in a set ofintervening roles between the learner and the subject matter. The adultknows his own standards and expectations. He no longer needs to be told, nor does he require the approval and reward from persons in authority. (Boyd, 1966, p. 180)

This is fully autonomous or self-directed, and adult learning. It is the learning of the person who is able to establish a learning goal when faced with a problem to be solved, a skill to be acquired, information that is lacking. Sometimes formally, often unconsciously, self-directed learners set their goals and define criteria for their achievement. They know (or find out) where and how and from what human and other resources to gather the information required, collect ideas and practise skills . They judge the appropriateness of the new skills, information and ideas, eventually deciding if the goals have been achieved, or can be abandoned. And in all this they use teaching programs of all kinds. A phenomenon of the Euro-American culture, which has been exported around the world, is that schools and universities are generally neglectful of learning programs, and preoccupied with sustaining and studying teaching and the work of professional teachers. This is a consequence in part of an inability to conceptualize more broadly, and also a reluctance to challenge one's own institutions. Although education is about both learning and teaching, educa tional institutions have focused too much and for too long on the latter, on teachers' intentions, to the exclusion, or at best subordination, of the equally relevant side ofthe educational relationship, intentional learning. Self-directed learning, if considered at all, is regarded as a careless and casual activity on the periphery of the educational field, hardly worthy of systematic study or major support.

One result of this neglect is that educators and their institutions grossly underestimate the numbers of people in education and the size and nature of the market for educational services. In U.K. estimates of participation in adult educationvaryfrom 15-22% (ACACE,1982)ofthetotalpopulation. In Canada it is about 20% (Tough, 1971). In the first national study of adult learning in the U.S.A., Johnstone and Rivera (1965) found 15% of the population were involved in institutionalized education. With some surprise they noted an unexpectedly large incidence of what they could only call "independent self study." This was deliberate and planned learning reported by interviewees who did not use professional teachers or courses, classes or educational institutions . Johnstone and Riviera concluded that this was a widespread, though previously overlooked form of adult education. Their discovery set offa wave of interest in what became known sometimes as independent learning, sometimes as self directed learning.

One of the most important empirical studies of this self directed kind of learning was Allen Tough's research in Canada. He focussed his attention on the ways in which adults plan their own learning, and then went on to investigate how they actually "teach themselves," including ways in which they obtain advice and help from other people. Although Johnstone and Riviera had been surprised at the extent of self-directed learning they encountered, there were earlier educators than Tough who had described, theorized, and hypothesized about the phenomenon. Tough's achievement was first to define self-instruction in measurable and, therefore, researchable terms, and then to begin and maintain an extensive program of empirical research. He defined self-instruction as, "a series of related episodes adding to at least seven hours. In each episode more than half a person's total motivation is to gain and retain certain fairly clear knowledge and skiU or to produce some lasting change in himself" (Tough, 1971, p. 6). Tough first conducted in-depth interviews with 66 adults, probing to help them recaU their learning during the year before the interviews, and to remember how they had set about learning. From this and many subsequent studies in eight or nine countries (Coolican, 1974; Hiemestra & Penland, 1981; Tough, 1976) the following picture of adult learning has emerged:

Before this research, most educators appeared to pay little attention to self- directed learning. They concerned themselves with those adults who came to classes and courses, and seemingly assumed that since the majority of adults were not interested in what was offered there, they were not interested in learning itself. Following Tough, there is now a greater willingness on the part of educators to find out what adults are interested in learning, and to provide help to this self-motivated, self-directed adult learning. This is a highly significant change in emphasis, for the "market" for adult education is virtually the whole adult population.

Also significant however, is that the teaching approach which best meets the needs of these learners is not one of control and direction but one that is helping and responsive. As pointed out by Hiemstra and Penland (1981, p. 1),

Even though the learner protects a personal control and pacing of the learning project, the constraints and opportunities of the environment cannot be ignored. Support requirements are real and consist of the numerous helping sources consulted by the learner during project development and completion.

These sources include tutors; friends and relatives; travel. They also include what I would call teaching at a distance through books, newspapers, magazines and newsletters, radio, television, films, tapes, and home computers. When asked why they like self-directed learning, Hiemstra and Penland's (1981) respondents answered:

Distance educators appear to be well qualified to assist learners in taking increasing amounts of control over the learning enterprise. The remainder of this paper deals with three key questions about self-directed learning and distance education. They are:

The variety seems almost infinite, but the majority of learning (76 % according to Hiemstra and Penland) is for some practical purposes, to do with the home, hobbies, crafts, sports, and recreation. There is considerable learning connected with work, among professional people especially, and also in topics about interpersonal relations. Only some 7 % is academic learning, and only 1% is learning for certification (Hiemstra and Penland, 1981).

Especially interesting in my opinion are the learning needs which arise as a consequence of each individual's development through the various life stages, as identified by developmental psychologists. Psychologically speaking, the years of adulthood are years of ever increasing individuation. In other words, as one gets older one becomes more peculiarly oneself, and more unlike other people in one's perceptions, interests, attitudes, ways of thinking, perhaps even one's appearance. Every person is a unique being, growing in his or her own way, in a continuous state of change from the primitive, most global, condition at conception to the most highly differentiated state and the most fully devel- oped self at the time of death. As we all experience birth, adolescence, and death, we also experience other, somewhat less dramatic, transitions through out adulthood. The research evidence in this area is by no means complete, but beginning with Charlotte Buhler's work in Germany in the 1930s there have been a number of important studies. These include the work of Erikson (1959), Havighurst (1948), Kuhlen (1968), and Neugarten (1968), and offer consider able agreement about the general nature of the main stages of adult develop ment. (A good summary will be found in Cross, 1981.)

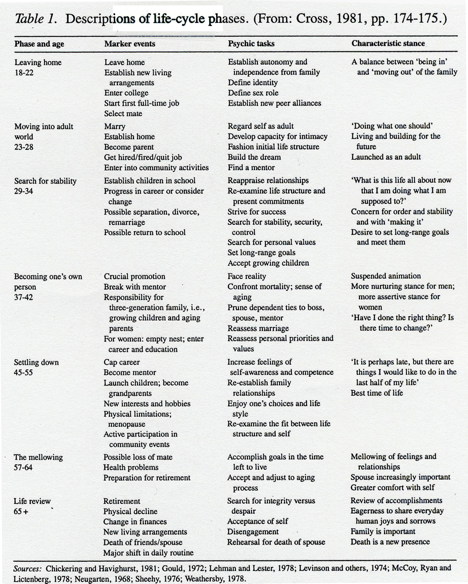

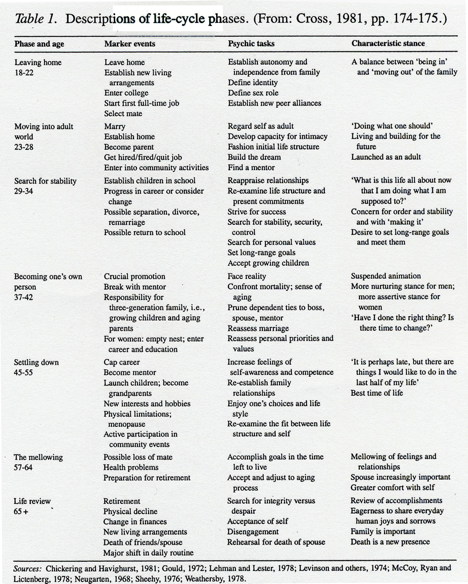

The findings of these researchers have two extremely important implications for distance educators. First, educators are becoming aware of the learning needs which accompany such developmental tasks as becoming a parent, or facing the difficulties and opportunities of mid-life change (Knox, 1979). "Readiness," says Cross, "appears to be largely a function of the socio-cultural continuum of life phases. The implication is that educators should capitalize on the 'teachable moments' presented by the developmental tasks of the life-cycle"(1981,p.238). A summary of such life-cycle phases is shown in Table 1.

The table indicates a vast area of adult learning needs which might form the basis of an extensive range of teaching programs. The second implication of this research is particularly significant for distance educators. It is apparent that the process of individuation of self means that the psychological context in which any person encounters any of these transitions will be different from that of anybody else Paradoxically life 's transihons are common to all, yet experienced differently by each individual, and in turn contribute further to the uniqueness of each individual Learning to cope with and grow through each life stage is different for each individua1, and educational programs to aid such learning must be designed to allaw individuals to meet their particular needs. In practice this might best be done through a combination of self direc~d learning and a wide range of teaching programs. Such a wide range would be accessed most easily through distance teaching.

Preparing programs of this kind is one of the aims of the Open University's Centre for Continuing Education. This part of the University produces courses and packs ofteaching materials designed to be used without tutorial support(i.e., more distant teaching). These teaching programs are intended "...to meet the learning needs of individuals at various stages of their lives in their roles as parents, consumers, employees and citizens, in the context of their family, workplace and community"(J. Calder and N. Farnes, quoted by Lambers& Griffiths,1983). For example, some of the subjects on which these distance teaching materials have been prepared are:

This question can be discussed with regard to both learning in life eyeledevelopment as it has just been introdueed, and with regard to more established and better understood aeademie programs.

With regard to life cycle learning, it was just suggested that what any particular individual needs to learn at any stage of the life cycle is speeifie to thatperson, so each person must choose what to learn, and also choose from the irnmense range of teaching programs. A distance education system that too~ such learning very seriously would give adequate human and financial re-' sources to establishing a sub-system between the course production centre purpose of this sub-system would be to give assistance to each individual in planning an educational program. In particular, it should help people to analyze their own immediate personal and social situations to decide if the need is for learning, and if so in what area, and using what teaching programs. Such a I system people to whom one has access on those occasions when one needs advice o maintaining health, in the other of learning. An advisor is needed who is part of no course structure, and preferably part of no institution. The advice should not be merely to take this course or that, but together with the learner - to choose this book, thattutor, this broadcast, that visit and project, so each learner builds a personal program aimed at his/her particular personal learning goal. Articles in the literature which have at least started the debate on this subject include those by Farnes and McCormick (1976), Watkins (1976), Moore (1980) and Williams, Calder and Moore (1981). A major report on the subject in Britain, "Links to Learning" (ACACE, 1979) advocated the use in such a system of both full time professional counsellors and part time volunteers, and suggested that such counselling could be offered through the public libraries.

Neither in Britain, nor any other country, have funds been found to set up a proper nation-wide comprehensive adult learning advisory service. There have been several small scale experiments, however, such as those reported by Butler (1981), Eagleson (1977), Murgatroyd and Redmond (1978), and Vickers an~ Springall (1979). Local library services in Britain often prepare directories a~ institutions in their area which offer teaching programs, and a national com puter based data bank of such programs is soon to be established. The services only give the enquirer information about courses though. They nothing to help individuals in goal determination, or in finding resources othel, than courses. Setting up a more comprehensive network will, I suspect, have to wait for a major political decision and that is unlikely until there is a more widespread understanding of the implications of a workless society.

The many other implications of self-directed learning for distance education systems cannot be explored fully here, but I would like to mention at least the following:

If adult learners are willing and able to be self-directing in-study, how might the educational institution, especially the institution of distance education, modify its teaching in order to give each learner the chance to exercise autonomy?

Malcolm Knowles (1970) in writing about "andragogy," the art and science of helping adults learn has made the following suggestions:

a. Provide a physical climate (if meeting face-to-face) and more important, a psychological climate that shows the learner is accepted, respected and supported, and in which there exists a spirit of mutuality between teachers and students as joint enquirers.

b. Put emphasis on self-diagnosis of needs for learning. This means giving the learner a way of constructing a model of the competences or characteristics aspired to - whether it be, for example, a good parent, good teacher, good mathematician; a way of diagnosing the present level of competence and of minimizing the gap between the desired level of competence and the present level.

c. Involve the learner in planning a personal program based on this self diagnosis, turning the needs into specific learning objectives, changing and conducting learning experiences to achieve these objectives, and evaluating the extent to which they have been achieved.

d. The tutor acts as a resource person, a procedural specialist, and a co- inquirer, and not try to make the other person learn.

e. The tutor helps the learner in a process of self-evaluation. This means that learners gather their own evidence about progress toward the educationalgoals they have set.

f. Place great emphasis on techniques that tap the experience of adult learners. There must be a distinct shift of emphasis away from transmittal techniques such as the lecture and assigned readings, toward discovery learning, especially in field projects and other techniques which give the learner a chance to be actively involved.

Several attempts have been made to apply ideas like these in higher education programs where there is both face-to-face and distance learning. The Empire State College (U.S.A.), St. Francis Xavier's adult education program (Can- ada), and the School for Independent Study at the North East London Polytech nic (U .K.), are some examples. In all these institutions, individual students can earn degrees by designing their own learning program, implementing and evaluating it. The North East London Polytechnic states:

We have dispensed with pre-arranged syllabuses and externally imposed assessments and have made exclusive use of students' own statements. These statements cover students' own self assessment of interests, abilities and achievements at the outset; their long term aspirations and more immediate educational goals; their detailed plans for learning and the details of their terminal assessment. (Stephenson, 1983)

Similarly in the St. Francis Xavier program, students must identify their own learning needs on the basis of an examination of previous performance and competence and present aspiration. They then describe their learning needs and a set of behavioural objectives, and devise a plan for achieving those objectives

A student may choose to work on his study program independently or as a member of a group. His learning objectives, his plan for achieving them and for evaluating his success are to be specified in writing. Faculty members will discuss the terms of the learning plan with the student. The final agreement between student and faculty will contain a systematic description of the student's learning objectives, the action research activity which he will follow to achieve these objectives, the type of help the requires from the university and a set of deadlines for achieving the various tasks. (St. Francis Xavier University Calendar, 1972)

In practice, the program planning process at both of the institutions just referred to is conducted face-to-face. Among St. Francis Xavier students implementation is very often in the student's own milieu, away from the teachers, and help is given at a distance by correspondence and telephone (Moore, 1976).

Even if we wanted to, is such an approach possible when distance is greater, as in for example the FernUniversitat and the Open University? In what consider to be the most exciting chapter in Distance Education, Liosa and Sandvold (1983) have made the best attempt so far to analyze the various ways in which students might be enabled to exercise freedom of choice within the didactical structure of a correspondence course. The authors tell us that in Norway a recent Adult Education Act insists that for an educational institution to receive public support it is,

Required to have an educational practice which secures the influence of the course participants, both as regards the form and the contents of the course. (1983, p. 293)

Ljosà and Sandvold comment:

In a traditional correspondence course the course material itself is supposed to be studied by all the students. The courses are rarely organized in such a way that the students are encouraged and practised in making personal choices based on e.g., their own qualification, interests or their own local milieu. Very few students are able, themselves, to emphasise certain parts and work less seriously withor completely skip - other parts of the study material. In practice this means that few students make personal choices within the course material. Most of them accept what the course developer has chosen for them, and go through the material without letting their own background consciously influence their work. (1983, p. 299)

Then they describe some of the choices which it is possible for students to make in a correspondence course. These include the freedom to choose materials on different levels, to choose material in accordance with personal interests, to select material from supplementary reading, and to find material and working projects in the local milieu. The student, they say can be placed in the centre of the learning process.

Instead of letting the course material choose for him/her the student himself/herself will be the active part, taking the initiative in the choices that have to be made . Through a long series of personal conscious choices the student will make his/her own course from the basic material that the correspondence course offers. (Ljosa and Sandvold, 1983, p. 299; my emphasis)

This is exactly what we expect self-directing learners to do. It is what the inventor described by James and Wedemeyer (1959, cited by Holmberg, 1983) did. It also is to encourage this that the Open University has tried to promote "informal use" of continuing education materials by producing a series of "packs" rather than highly structured courses.

I would like to end by asking you to turn away from questions about program design, program content, the structure of systems, and all the other rather technical matters discussed so far, and consider the purpose of all this activity. Education is concerned with issues more fundamental than how people learn, how they are taught or even what they are taught - for what and how they are taught are derived from the values and aspirations of society itself. Those who seek to influence and change society, or indeed to keep it as it is, call upon education to serve the ends of one or another particular set of values. They, and like it or not, we who practice in education are guided by value judgements about human nature, and in particular about the nature of people's freedom of thought and action. To what extent, if at all, are our futures controlled by supernatural force? To what extent, if at all, are we subject to immutable forces in history and in society? To what extent, if at all, is each of us free to direct the present and to shape the future? Our every action in education is guided by our personal responses to these questions of freedom and authority, and our every action in turn contributes to establishing and maintaining within our own circles of influence, the values which those responses reflect.

Distance teaching, having the power associated with industrialization in education can be a more efficient and effective force for achieving either enhanced learner autonomy or greater control by teachers and educational institutions. In distance education we are faced by the same value judgements about freedom and control as were our predecessors in more simple forms of education, but because of the impact of modern communications media and large scale delivery systems, the consequences of our choice or indeed our failure to choose, are more wide reaching.

It is important that those of us who believe in the importance of individual freedom be on our guard. It is important that we not only design and teach good programs, but that we think, write, and argue for learner autonomy. It also is imp rather than teachers or institutions, and is not used as a means of state control and social direction. Perhaps most important, we must play a part in adminis- tration and management, which is not always very attractive to persons whose first wish is to be helpers of other people. It is very important at this particular time, as one generation of administrators and managers gives way to another. The previous generation worked in distance education when it was regarded by the world outside with suspicion and hostility, or at best was ignored. The leaders in our field were men and women with a vision that modern technology could be used to free people from constraints on their learning - the constraints of geographic isolation, being housebound, being disab~ed, or having to hold down a job and therefore not able to study. Their ends were human, though the y means they employed were technological.

Distance teaching has become successful. It is important that its management remains in the hands of people who are motivated to sene others, not to sene the machine . In other words, we must be alert to defend those human values that have been the traditional concern of distance educators, especially the values of learner freedom, individualism and self-direction.

This paper is derived from Ziff-Papiere # 48, which was a transcript from a presentation given by the author at FernUniversitat, Hagen, West Ger- many, 1983.

Advisory Council on Adult and Continuing Education (ACACE). (1982). Adults: Their educational experience and needs. Leicester, A.C.A.C.E.

ACACE. (1979). Links to Learning: A report on educational inforrnation advisory and counselling services for adults. Leicester, A.C.A.C.E. Boyd, R. (1966) . A psychological definition of adult education. Adult Leadeship, 13, 160-162/180-181.

Butler, L. (1981). The Educational Advisory Senices Project. Teaching at a Distance, 19, 85-86.

Coolican, P.M. (1974). Self-planned learning: Implications for the future of adult education. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press.

Cross, P. (1981). Adults as learners. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Eagleson, D. (1977). The Educational guidance senice in Northern Irel: Teaching at a Distance, 9, 13-17.

Erikson, E. (1959). Identity and the Life Cycle. Psychological Issues, monograph 1.

Farnes, N., & McCormick, R. (1976). The education well being of the community generally. Teaching at a Distance, 6, 5-15.

Havighurst, R. (1948). Developmental tasks and education. New York: McKay Co.

Hiemstra, R., & Penland, P. (1981). Self-directed learning. Presentation at Commission of Professors of Adult Educahon. Anaheim, California.

Holmberg, B. (1983). Counselling - for whom andfor what purpose ? Unpublished contribution to conference on counselling in distance education. Cambridge, England.

James, B., & Wedemeyer, C. (1959). Completion of university correspondence courses by adults. Journal of Higher Education, 30(2), p. 93.

Jeffcoate, R. (1981). Why can't a unit be more like a book? Teaching at a Distance, 20, 75-76.

Johnstone, J. W., & Rivera, R. J. (1965). Volunteers for learning. Chicago: Aldine.

Knowles, M (1970). The modern practice of adult education. New York: Association Press

Knox, A. (1979). Programming for adults facing midlife change. New Directions for Continuing Education, 2.

Kuhlen, R. (1968). Developmental changes in mohvation during the adult years. In B.L. Neugarten (Ed.), Middle age and aging. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lawson, K. (1974). Learning sih~ations or educational sih~ations. Adult Education. Leicester: National Instihute of Adult Education.

Lambers, K, & Griffiths, M (1983). Adapting materials for informal learning groups. Teaching at a Distance, 23, 30-39.

Ljosa, E., & Sandvold, K. (1983). The student's freedom of choice within the didactical structure of a correspondence course. In D. Sewart, D. Keegan, & B. Holmberg (Eds.), Distance Education: International perspectives. London: Croom Helm.

Moore, M. (1976). Specifications of two independent study programs. Independent Study among adult learners, chapter III. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Wisconsin, Madison. University microfilms 7620127.

Moore, M. (1977). On a theory of independentsh~dy. ZIFF Papiere 16. Hagen, FernUniversitat, Zentrales Institut fur Fernstudienforschung.

Moore, M. (1980). Continuing education and the assessment of learner needs. Teaching ataDistance, 17, 26-29.

Murgatroyd, S., and Redmond, M. (1978). Collaborative adult education counselling. Teaching at a Distance, 13, 18-26.

Neugarten, B.L. (Ed.) (1968). Middle age and aging. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

St. FrancisXavierUniversity (1972). Calendar. Antigonish, Nova Scotia.

Stephenson, J. (1983) . Higher education: School for Independent Study. In M. Tight (Ed.), Adult learning and education. London: Croom Helm/The Open University.

Tough, A. (1971). The adult's leaming projects. Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Tough, A. (1976). Self planned learning and major personal change. In R.M.

Smith (Ed.), Adult learning: Issues and innovations. DeKalb, Illinois: Eric Clearinghouse in Career Education.

Watkins, R. (1976). Counselling in continuing education. Teaching at a Distance, 6, 35-39.

Wedemeyer, C.A. (1981). Learning at the back door: Reflections on non traditional learning in the life span. Madison, Wisc.: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Williams, W., Calder, J., & Moore, M. (1981). Local support services in continuing education. Teaching at a Distance, 19, 40- 58.

Vickers, A., & Springall, J. (1979). Educational guidance for adults. Teaching at aDistance, 16, 62-64.