Developing a System for Audio-Teleconferencing Analysis (SATA) |

A model is presented which represents the institutional process as it applies to a multi-site audio-teleconference class remote from a host institution. This model emphasizes antecedents as determinants of the instructional process and outcomes. Although many of the antecedents and outcomes have been investigated, comparatively little attention has been attached to investigating the instructional process. This paper describes the development of a system for audio-teleconferencing analysis (SATA). The system is based on classroom observation research and analyzes the "on air" interactions which occur during an audio- teleconference class. SATA was developed using the audio- teleconferencing tapes from a multi-media Women's Studies course offered by Memorial University of Newfoundland. Although no attempt was made to investigate the antecedents or outcomes of the course, some preliminary analysis is presented as are future plans to investigate the instructional model described in the paper.

On montre un modèle qui représente le processus institutionnel tel qu'il s'applique à une classe donnée par téléconférence simultanément en plusieurs endroits et éloignée de l'institution mère. Ce modèle met en valeur les antécédents qui ont déterminé le processus institutionnel et ses résultats. Bien que nombre des antécédents et des résultats aient été étudiés, en revanche peu d'attention a été accordé à l'étude du processus institutionnel. Cette communication décrit le développement d'un système d'analyse des téléconférences (SATA). Le système se base sur des observations de classe et analyse les actions réciproques qui se passent en direct lors d'une classe donnée par téléconférence. Le SATA a été créé en utilisant les bandes des téléconférences d'un cours se servant de média multiples, offert par le Département des Etudes de la Femme à l'Université Memorial de Terre-Neuve. Bien qu'on n'ait pas essayé d'enquêter sur les antécédents et les résultats du cours, on donne une analyse préliminaire ainsi que des projets de recherche sur le modèle d'enseignement décrit dans cette communication.

Much of the research on audio-teleconferencing has been from the social psychologist's perspective and has been concerned with such topics as the relative efficacy of different media and their potential to substitute for face-to-face meetings. From this work has emerged constructs such as Social Presence (Short, Williams & Christie, 1976) and Technological Immediacy (Heilbronn & Libby, 1973) as well as a general understanding of the role of the medium in communications. For the distance educator, however, an investigation of this powerful tool may be more fruitfully approached from the standpoint of instructional theory.

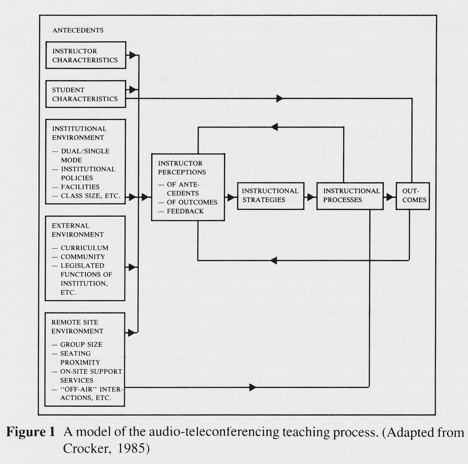

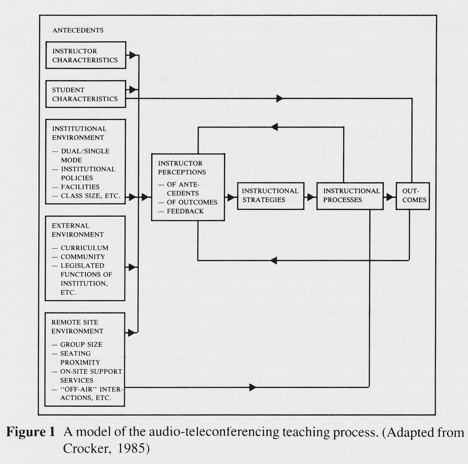

A model developed by Dr. R. Crocker and associates (1985) to depict the basic classroom teaching process can be adapted to the audio- teleconferencing situation (Figure 1). The model emphasizes the antecedents of instruction in an attempt to develop an explanatory as opposed to the usual correlational approach to investigating instruction. For the distance educator instructing from a host institution to a multi-site teleconference class, these antecedents can be more complex and numerous than those usually involved in face-to-face instruction. Thus not only will traditional factors such as instructor and student characteristics influence instructor perceptions, but so will those antecedents associated with the remote site environment, as will instructional factors peculiar to the milieu of distance education. According to the model, the role played by these antecedents will be to shape instructor perceptions which in turn will determine strategies, instructional processes and outcomes.

The dynamic nature of the proposed model does not confound common sense but does indicate the difficulty for researchers who want to develop an explanatory model of instruction. Many of the elements of this and any other instructional model have been investigated without difficulty in the area of distance education. Thus surveys ad nauseam have been conducted on student backgrounds and characteristics, similarly for instructor preferences and perceptions; and, student outcomes have been correlated with virtually everything except their eye colour. More difficult to investigate is the instructional process, i.e., what goes on in the teleconference session. It is apparent from the instructional model that an understanding of this element is pivotal in developing an insight into why teleconference sessions are the way they are.

The research reported in this paper deals with the development of a system for analysing interactions that take place in a teleconference session. In the context of communications theory, considerable interest has been shown in the study of the interactions that comprise teleconference sessions. While some attempts have been made to study these interactions from the standpoint of instructional theory (Chang Yit cited in Edison- Swift, 1983; Martin, 1980), these studies were not carried out in the context of an instructional model as proposed earlier. Most interaction measures, as reported in the literature, appear to be far removed from the reality facing distance educators; e.g., number of adjectives divided by number of verbs (Williams, 1972), word counting in linguistics classes (Stoll et al., 1976), proportion of floor changes which immediately follow a question (Ruther & Robinson, 1978), gross speaking turns (Carey, 1981). These and other studies appear to have been less concerned with characterizing the instructional climate of teleconference sessions in an attempt to understand the teaching mechanism, but more commonly have been from the standpoint of investigating dyadic communication.

The System for Audio-Teleconferencing Analysis (SATA) was developed utilizing tapes of one-hour teleconferences from a multi-media Women's Studies off-campus credit course offered by the School of Continuing Studies and Extension of Memorial University of Newfoundland in the Fall Semester 1986. These teleconferences afforded a weekly real time link of professor with students spread over eight sites in rural Newfoundland and Labrador. Teleconferencing has the capacity to be the sole or the principal course delivery system. In this case, the course also included pre-packaged print, video and film components.

The SATA follows in the tradition of observational research. Evertson and Green (1986) discussed the "methods and factors involved in the design and implementation" (p. 189) of such research, noting that "observation, as an approach to study educational processes and issues, has a rich and varied history (p. 162). The development of the SATA grew out of the theoretical framework developed by Crocker et al. (1985) and, in particular, the work of Stallings and Kaskowitz (1974). The latter used a classroom observation system (the Follow Through Classroom Observation Instrument) as part of their evaluation of Project Follow Through Classrooms in the United States which were funded to maintain the gains of children in Head Start Programs through the early years of public schooling. Their Five-Minute Observation (FMO) which was utilized "to record interactions among people in the classroom" (p. 25) was of particular interest in this present research.

The FMO observations are "structured as a language, with the codes forming intelligible sentences" (p. 28). Four categories ("carefully defined to include elements of educationally significant events") (p. 28) are incorporated into each coding sequence: "`Who does the action?,' `To Whom is it done?,' `What is done?,' and `How is it done?'" (p. 28). These categories are coded in sequence to form a sentence (subject, verb, object) which represents one interaction. As Stallings and Kaskowitz explained:

The Who and To Whom codes are used to designate the participants in an interaction. These codes make it possible to designate the person or group of persons initiating or receiving an action._The What codes are used to designate the kinds of interaction - such as questions or statements - that have occurred between the participants. The How column codes are modifiers. They supply additional information (p. 28).

The vocabulary of the FMO language (the coding choices within each category) identifies the classroom roles of the persons designated in the Who and To Whom categories and the type of events in the What category. In the How category, the vocabulary describes or modifies the initiator or the event. Thus, it is possible to form strings of code sentences, each one composed of Whom, To Whom, What and optional How codes which together depict the interactions occurring in classrooms.

The present research was able to utilize two of the three basic rules of syntax developed by Stallings and Kaskowitz for the FMO language. These were:

The third rule pertains to vocabulary elements which indicated How an interaction was performed. These vocabulary elements were omitted in this study in favour of a "context" category which will be explained shortly. In addition, a "status" category was utilized and there were several changes in vocabulary elements which identify events and participants. These were made necessary by inherent differences between a live classroom of young children (the environment for which Stallings and Kaskowitz designed their system) and the teleconferencing environment (adult students, spread singly or in small groups over a wide area, working without visual communication between sites) which prompted the present research.

Thirteen audio-teleconferences were recorded on audio-cassette. These audio recordings were subsequently transferred to half-inch video-cassette along with time code. For easy reference, the time code began at zero at the start of the teleconference recording. Using a videotape playback machine, coders located predesignated segments on each tape and observed the start and stop times of utterances as they heard them. The video tape machine allowed easy starting, stopping, reviewing and fast- forwarding of the tapes with the time code in view, so that the coders could calculate the duration of verbal utterances, check their coding decisions or proceed to the next section of the tape scheduled for coding.

A time sampling technique was adopted whereby five three-minute segments were chosen from each one-hour tape. In each case, these segments were: minutes 1–4, 14–17, 28–31, 42–45 and 55–58. This selection provided samples of the beginning and end of the teleconferences as well as three samples from the middle. Within each segment every verbal utterance was coded. Where an utterance occupied more than five seconds, the Duration was noted utilizing the "repeat" code which will be explained below. Utterances were coded according to the following categories and vocabulary elements in each. Where vocabulary elements are not self- explanatory, brief definitions are provided:

Who (initiator of utterance)

Instructor:

Student: An individual at one of the teleconferencing sites

Site: The person(s) at one teleconferencing location

Class: Members of all sites together

Other: Teleconference operator, class member(s) who could not be categorized above

To Whom (person(s) to whom utterance is directed)

Instructor

Student

Site

Class

Other

These elements have identical definitions to those in the Who category.

What (type of utterance)

Cognitive - Memory (M): A narrow question which "calls for answers that are a reproduction of facts, definitions or other remembered information" (Cunningham, 1971, p. 91).

Example: How do you define the word communication? (p. 101).

Convergent (C): A narrow question that requires the person answering "to put facts together and construct an answer." This type of question is narrow "because there is usually one `best' or `right' answer" (p. 93).

Example: What is the difference between language and communication? (p. 101).

Divergent (D): A broad question which permits "more than one acceptable response_.A divergent questions asks the person responding to organize elements into new patterns that were not clearly recognized before" (p. 96).

Example: If you were a sea creature, how would you communicate with other sea creatures? (p. 102).

Evaluative (E): A broad question which requires the person "to judge, value, justify a choice or define a position. It is the highest level of questioning. It involves the use of the cognitive operations from all three of the other levels" (p. 99).

Example: How do you feel about the argument that both uses of the words "language" and "communication" are acceptable as long as they are understood by the group? (p. 102).

Question (Q): A question which cannot be classified into one of the above categories.

Request (R): Asks for a response free of argument or speculation. There is one expected, acceptable response that is to be carried out verbally or nonverbally.

Response (Rs): A verbal response to a request to a question or to feedback.

Instruction or Explanation (Ie): Verbally giving new information to others, reviewing material or explaining, but not when it is in response to a request, question or feedback.

Comments or Remarks (Cm): These are statements that do not fall in the Rs or Ie categories.

Acknowledgement (A): An indication that a response, product or behaviour is recognized or agreed with. Another form of acknowledgement is to repeat someone else's statement immediately.

Feedback (Fp, Fn): An attempt to correct or modify a response, product or behaviour, whereas acknowledgement is simply recognition or agreement. Fp is correction or modification delivered in a positive, supportive way, Fn is given negatively.

No Response (No): A pause of five seconds or longer.

Identification (Id): The speaker gives his/her name or the name of the site at which he/she is located.

Examples: Mary here.

Stephenville here.

Other (O): An utterance which cannot be classified under any of the What vocabulary elements above.

Context (the situation in which the utterance takes place)

Academic (A): The utterance pertains directly to the academic material of the course.

Procedural (P): The utterance pertains to actions, events or procedures that are necessary to the course but do not involve the study of academic material directly. Examples are setting assignments, locating page numbers or specifying times for meetings.

Social (S): The utterance is social or interpersonal in nature and does not relate directly to the academic material or procedures necessary to the course.

Other (O): The situation cannot be classified according to the vocabulary elements above.

Status

Repeat (R): When the sentence being coded occupies more than a five-second interval, "repeat" is coded every five seconds to indicate the total duration of the utterance.

Simultaneous (S): Coded to indicate that the utterance occurred at the same time as the immediately proceeding sentence code. In our teleconferencing system this could only happen when the instructor, the one person with an open microphone, talked "on top of" a student.

Cancel (C): Means disregard this line. Used when the coding on that line contains errors.

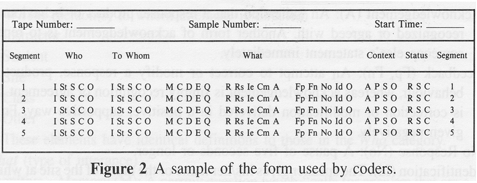

Four university students were trained on the coding system for a period of approximately eight hours spread over two days. Practice utilized samples from the teleconference tapes that had not been designated for inclusion in the research. After the training period, the coders worked in pairs. Each pair worked independently but the members of a pair were expected to discuss each coding decision and arrive at a common decision which each coder entered on a coding form (Figure 2). This was carried out in all instances. The decision to have coders work in pairs was based on the premise that it would result in more thoughtful decisions, reduce the tedium associated with the work and increase efficiency.

In calculating the reliability of coding, the decisions of one member of each of the two pairs were compared. Over more than 500 coding decision, the agreements were greater than 90%.

As indicated earlier, this paper is primarily concerned with the development of a technique for the objective observations of the interactions which comprise an audio-teleconference session. As such, no attempt was made to investigate the antecedents or outcomes of the Women's Studies course or to establish any of the relationships suggested by the model depicted earlier. Despite this, a preliminary analysis of the data reveals some interesting information about the teleconference sessions of the Women's Studies course.

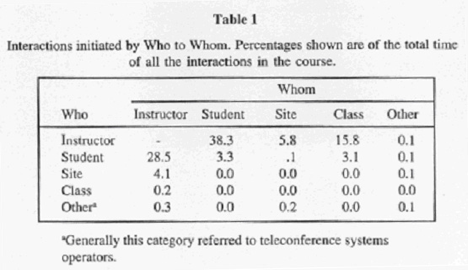

Table 1 shows the total interactions initiated by Who to whom for the whole course. The data are reported as percentages of the total time of all interactions; however, it should be noted that because all interactions were associated with a minimum of one five-second interval, the result might be to overemphasize interactions such as acknowledgements which could have been shorter than five seconds in length. As might be expected, most of the time was spent on interactions initiated by the instructor, 60.0% compared to 39.5% initiated by students either individually or in groups. Only 6.6% of interactions occurred among students.

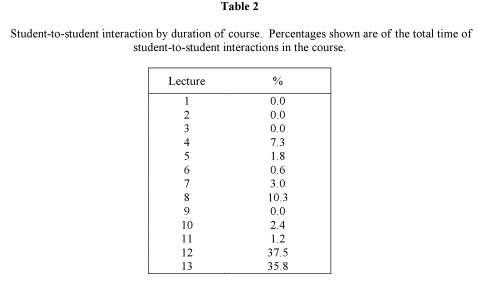

Table 2 shows the student-to-student interactions by duration of the course. Overall, it is apparent from the data that student-to-student interaction increased as the course progressed. As previously mentioned, this study made no attempt to examine instructor strategies or student familiarity with teleconferencing, and thus plausible hypotheses to explain this observation were not tested. It might be speculated, however, that if the course had been taught by face-to-face instruction, the discursive nature of the course material might have been expected to prompt more student-to-student interaction. If indeed this is correct then techniques to develop these kinds of interactions need to be identified and imparted to teleconference instructors.

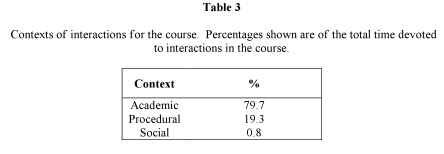

Table 3 shows that most of the interactions were Academic, although Procedural interactions occupied nearly 20% of the total time. As anticipated, these Procedural interactions occurred mainly at the beginning and end of each session and the proportion of the total interactions, as a consequence, is distorted because of the times of the samples taken.

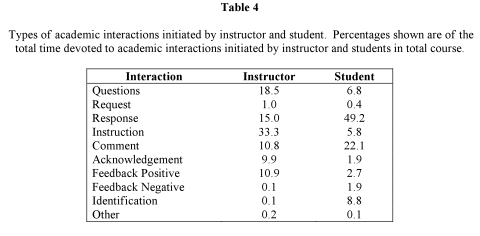

The types of Academic interactions are reported in Table 4. The reported percentages reflect the traditional roles of instructor and student. The largest percentages of the instructor-initiated interactions are instructions and questions, while nearly half of the student-initiated interactions are responses. Also of note were the low percentages of negative feedback reported for either the instructor or students.

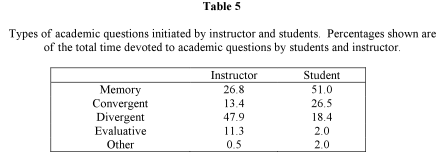

The types of questions asked are of particular significance from the standpoint of instructional technique. The data in Table 5 show that the majority of instructor-posed questions were divergent, presumably reflective of the course content and emphasis. The most common category of student-posed questions asked was memory, to solicit factual information.

It is the intent of the authors to use SATA to explore aspects of the audio-teleconferencing instructional process. By using SATA, it is hoped to identify subjects and patterns of interaction and to investigate whether these are characteristic of specific instructors or content areas. In light of the instructional model presented earlier, other areas of investigation will include the effects of various antecedents such as "off-air" behaviours, group size, student and instructor characteristics, etc. on interaction patterns and in turn the relationship of these interaction patterns to cognitive and attitudinal outcomes.

Carey, J. (1981, December). Interaction patterns in audio- teleconferencing. Telecommunications Policy, 304–314.

Crocker, R.K. (1985). The use of classroom time: A descriptive analysis. St. John's: Institute for Educational Research and Development, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Crocker, R.K., Brokenshire, G. and Boak, T. (1978). Teaching strategies project: Manual for classroom observers. St. John's: Institute for Educational Research and Development, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Cunningham, R.T. (1971). Developing question-asking skills. In J.E. Weigand (Ed.), Developing teacher competencies (pp. 81–130). Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Edison-Swift, P.D. (1983). A study in teleconference interaction analysis. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin.

Evertson, C.M., & Green, J.L. (1986). Observations as inquiry and method. In M.C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching, 3rd edition (pp. 162-213). New York: MacMillan.

Heilbronn, M., & Libby, W.L. (1973). Comparative effects of technological and social immediacy upon performance and perceptions during a two-person game. Paper presented at the annual convention of the American Psychological Association, Montreal.

Martin, Y.M. (1980). An analysis of an experimental university course via satellite: Implications for interactive teaching-learning systems. In L.A. Parker & C. Olgren (Eds.), Teleconferencing and interactive media. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin - Extension Press.

Rutter, D.R., & Robinson, B. (1979). An experimental analysis of teaching by telephone: Theoretical and practical implications for social psychology. In G.M. Stevenson & J.H. Davis (Eds.), Progress in applied social psychology, Vol. 1. London: John Wiley.

Short, J., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The social psychology of telecommunication. London: John Wiley and Sons.

Stallings, J.A., & Kaskowitz, D.H. (1974). Follow through classroom observation evaluation 1972-3. (SRI Project 7370). Stanford, California: Stanford Research Institute.

Stoll, F.C., Hoecker, D.G., Kreuger, G.P., & Chapanis, A. (1976). The effects of four communication modes on the structure of language used during cooperative problem solving. The Journal of Psychology, 94, 13-26.

Williams, E. (1972). The results of analyses of transcripts from the pilot experiment on communication medium and interpersonal attraction. London: Communications Studies Group, Long Range Research Paper, No. 30.