Approaches to Studying Research and Its Implications for the Quality of Learning From Distance Education |

This paper reviews the literature on the process phase of learning which is concerned with student's approaches to studying. Most of this research has focused on students in full-time, face-to-face study. This paper discusses the appropriateness of the research to distance education.

The relationship between various constructs arising from the approaches to studying research and academic outcomes is then examined. For distance education, surface approach or a propensity towards rote- learning appears strongly related to persistence.

The final part of the paper considers ways in which approaches to studying, and particularly surface approach, can be influenced by input variables. For students who habitually employ a surface approach, study skills initiatives of certain types are needed to teach the students how to employ a deep approach. Other students may normally employ a deep approach but such factors as assessment demands, workload, flexibility of courses and their interest to students can induce a surface approach. The implications for curriculum and instructional design of distance education courses are discussed.

Cette communication revoit ce qui a été écrit sur le processus de'apprentissage concernant la façon dont les étudiants abordent l'étude. Une grande partie de cette recherche se concentre sur les étudiants réguliers, à plein temps. Cette communication discute de l'applicabilité de la recherche à l'enseignement à distance.

On examine ensuite la relation entre les différents éléments qui proviennent des approches sur la recherche et les résultats académiques. Pour l'enseignement à distance, l'approche de surface ou une tendance à la mémorisation apparaît fortement liée à la continuité.

La dernière partie de la communication considère comment l'approche à l'étude, et plus particulièrement l'approche de surface peut être influencée par des variables ajoutées. Pour les étudiants qui ont généralement une approche de surface, certains types de méthodes pour améliorer l'étude seront nécessaires pour montre à l'étudiant comment employer une approche d'étude en profondeur. Il se peut que pour d'autres étudiants, utilisant une approche en profondeur, des facteurs tels que des exigences d'évaluation, des charges, la flexibilité des cours et leur intérêt pour les étudiants amènent à une étude de surface. Les implications pour le programme et le format d'enseignement des cours de l'enseignement à distance sont discutées.

Much research in higher education has used an input/output model. Input variables such as instructional design or teaching method have either been observed or systematically varied and have been linked to output variables such as grades or degree class.

Much less attention has been given to the intermediate step of process. Examination of the process phase considers the question of how students learn. Research on the process phase gathers data on the way in which students approach their study tasks, and also on the learning styles they commonly employ.

Reliance on an input/output model tends to be associated with an overemphasis on the quantitative measures of learning outcomes. Measurements associated with the output phase commonly quantify the number of ideas remembered, facts learnt or objective test questions answered correctly. The research on the process phase, to be reviewed in this paper, has been concerned with more qualitative issues such as whether students aim to understand what they read and whether their intention is to distill essential arguments from an article and relate new ideas to those previously assimilated.

The purpose of the first section of this paper is to review briefly the growing body of literature associated with approaches to studying and student learning styles. The body of knowledge has mainly been developed through studies on students in full-time tertiary study; the results have as yet had little impact on the distance education literature. The results of some research with distance education students are then presented to show that the approaches to studying findings are appropriate to distance education. The paper then goes on to discuss implications for distance education arising out of this novel line of research and the concepts in student learning styles which it has spawned.

The literature review is divided into sections, each section dealing with the research of a nominally independent research group; however it is pointed out that as the research has progressed, this categorization has become increasingly arbitrary because the groups have interacted increasingly and have influenced each other's work.

The first section reports the work of the Gothenburg group which was the first to focus on learning in higher education from the perspective of the student. The following sections consider the works of Pask and Biggs who independently have developed concepts that are similar and also complementary to those of the Gothenburg group. Finally the work of the Lancaster group is considered because it brought together the work on approaches to studying of the Gothenburg group, and the learning styles of Pask, and embodied it in an Approaches to Studying questionnaire.

This literature review is not intended to be a comprehensive review, but rather to introduce the reader to key research in this important new area of knowledge. For a more complete survey the interested reader should consider Marton, Hounsell and Entwistle (1984), and Entwistle and Ramsden (1983).

The pioneering work in this area was by researchers from Gothenburg University. The Gothenburg group's research concentrated on the way in which students approached the task of reading substantial academic articles. Students were invited to read the articles at their own pace using their normal approach. After reading the article the students were interviewed to determine what they had learned, how they had approached the task and their normal behaviour when reading academic articles. The interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed. The transcripts were then read through several times, usually by independent judges. The data examined first for internal consistency and then for similarities between interviews. Finally, explanatory constructs of emerging patterns were derived and checked against the transcripts (Svensson, 1976). The style of research has been christened phenomenongraphy (Marton, Hounsell & Entwistle, 1984).

An important dimension in approach to studying and level of understanding which appeared from the study was the distinction between a deep and a surface approach (Marton & Saljo, 1976a and 1976b). Students who employed a deep approach to reading the articles searched for the meaning of the article by examining the author's arguments. They were able to distill out the main point the author was trying to make. They related evidence and arguments to their own knowledge and critically examined the evidence presented for the author's arguments.

By contrast, those employing a surface approach tried to rote-learn information they considered important: rather than seek an understanding of the overall meaning of the article, they attempted to memorize details which they felt might serve to answer later questions.

Svensson (1977) related the propensity to employ a deep or surface approach with examination performance. Those classified as using a deep approach passed a far greater proportion of their examinations than those who normally employed a surface approach. Svensson also found that those employing a deep approach tended to study for longer periods as the search for understanding made the work more interesting. The tedium of rote-learning meant that those employing a surface approach spent less time studying.

The type of questions students were asked was found to affect the approach to studying adopted by students (Marton & Saljo, 1976b). One group of students was asked questions related to the meaning of the article. Another group was asked about points of detail. After facing repeated factual questionning, those students capable of adopting a deep approach eventually used a surface approach in the experiments. However those who habitually employed a surface approach found it difficult to adopt a deep approach when faced with meaning-oriented questions.

Pask observed the approach of students who had been set experimental learning tasks such as the discovery of classification principles (Pask & Scott, 1972). Pask (1976a and b) reported a distinction in the strategies employed by the students in the experiments. One group employed one limited hypothesis at a time. By contrast the holist group adopted a more global approach that tested more complex hypotheses which related several properties simultaneously.

The serialist and holist strategies are appropriate descriptions for the approaches to individual learning tasks or experiments. When students habitually adopt a particular strategy it can then be called a learning style. The learning style associated with the serialist strategy is called operation learning and is concerned with mastering procedural details using a step- by-step approach. Comprehension learning is the learning style of the habitual user of the holist strategy. Comprehension learning has been characterized as building descriptions of the knowledge.

Versatile students are able to adopt their learning strategy to the specified task and so show the signs of both learning styles. Other students consistently display one style rather than the other regardless of the learning task.

Students who display one style to the exclusion of the other may be sufficiently inflexible in their learning style that the style borders on a learning pathology. The learning pathology associated with an excessive use of the serialist strategy has been called improvidence. Improvident students are unable to see the way in which elements of knowledge relate to one another to form an integrated whole. These students do not make any use of analogies. The opposite learning pathology is globetrotting which is an excessive extreme of the holist strategy. Students who globetrot jump to conclusions too hastily, drawing conclusions without proper considerations of the evidence. Often this closure occurs prematurely. They are over-ready to draw analogies, often irrelevant or inappropriate ones.

Biggs (1978) divided the study process complex into three components - values, motives and strategy. Biggs (1979) reports a study process questionnaire which has three dimensions of study process, each with a motivational and a strategy component.

The utilizing factor is related to the surface learning dimension of Marton and Saljo (1976a) in that accurate reproduction and syllabus- boundness feature in study strategies. The students tend to be at university with the aim of obtaining paper qualifications; fear of failure in tests act as a shorter term motivational drive.

The second dimension is related to the deep approach. Students in this group study because of intrinsic motivation or interest in the subject for its own sake. In their reading, therefore, they seek the real meaning of the work. The final achieving dimension describes the approach of students who are motivated by the satisfaction of winning in a competitive context. The strategy component consists of a highly organized, systematic approach to studying.

The Lancaster group used both qualitative and quantitative research methods. It developed an inventory (Ramsden, 1983) so that a larger group of students could be examined for evidence of the learning styles and approaches to studying hypothesized by Pask and the Gothenburg school. Concepts developed by these researchers were incorporated into the Lancaster inventory. There was also interaction with the work of Biggs which was taking place simultaneously. The work of the Lancaster group is described by Entwistle and Ramsden (1983).

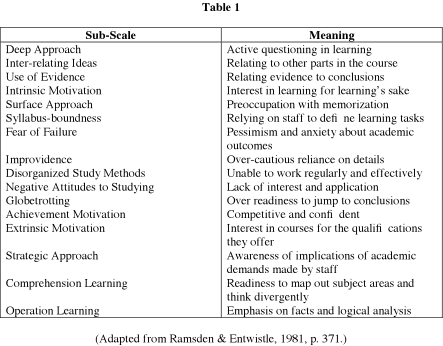

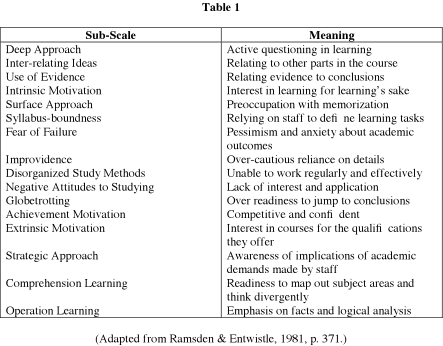

The "Approaches to Studying" inventory was developed through a number of pilot versions with factor analysis at each stage to group together variables which inter-relate and to check the consistency and validity of the inventory (Ramsden & Entwistle, 1981). The final research version of the questionnaire consisted of 64 items which contributed to 16 sub-scales. The sub-scales are listed in Table 1 together with their meaning. The table acts as a useful summary of the concepts and dimensions mooted by this body of research.

Ramsden and Entwistle (1981) used the inventory to search for relationships between students' approaches to studying and the characteristics of the departments in which they were taught. The survey was of 2208 students in 66 departments of British higher education institutions. They concluded that departments which were rated highly for their teaching and offered freedom in learning were the more likely to produce students who employ a deep approach.

The research reviewed in this article has not so far been cited to any great extent in the distance education literature. Before advocating its significance, it is first necessary to demonstrate that the constructs, derived from research on students in full-time study, are still relevant to the part- time distance learner. On face value it would seem that the body of knowledge should be appropriate because the research subjects were usually students reading substantial pieces of work, and reading is the major activity of distance learning.

Harper and Kember (1986) demonstrated that the constructs are applicable in distance education in a comparison of students in mixed mode institutions. The survey was of 1095 students at Capricornia Institute and the Tasmanian State Institute of Technology, two institutions in the advanced education sector in Australia. There were 779 respondents from representative subjects offered in both modes in the two institutions.

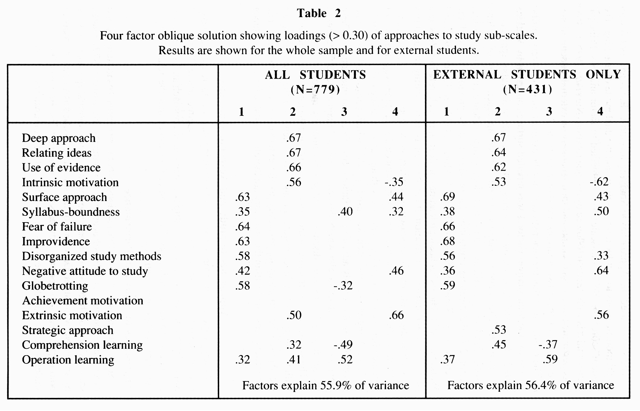

The survey used the Approaches to Studying inventory (Ramsden, 1983) with slight modifications to suit local terminology and the dual mode of teaching. The student scores for the 16 sub-scales were subjected to factor analysis. Principal factor analysis with iteration followed by oblique rotation (Nie et al., 1975, p. 468) was performed on the total sample and then separately on external students alone. The results of these two analyses are shown in Table 2.

The results show that the factor structure for the external students is very similar to that for the total sample. Factor 1 was labelled surface/confusion by Watkins (1982). It has high loadings on sub-scales which indicate undesirable approaches to studying. The highest loadings are on surface approach, fear of failure, disorganized study methods and the pathologies improvidence and globetrotting. Factor 2 is the meaning orientation factor identified by previous users of the inventory (e.g., Ramsden & Entwistle, 1981; Morgan, Gibbs & Taylor, 1980, and Watkins, 1982). The factor has high loadings on deep approach, relating ideas, use of evidence and intrinsic motivation. It can be seen as incorporating the qualities of scholarship traditionally espoused by tertiary education.

Each of the sub-scale scores were also subjected to a three-way analysis of variance between mode, subject and sex with age as a covariate (Nie et al., 1975, p. 398). A regression approach was used (p. 407) which partitioned individual effects by simultaneously adjusting for factors, covariates and interactions. There were a number of sub-scales which showed significant main effect differences at the level p<0.005 by age, discipline and sex but none by mode.

The similar factor structure of the external sample and the total sample, together with the analysis of variance results, are taken as evidence for the applicability of the Approaches to Studying inventory to the external mode of teaching. The constructs subsumed within the inventory are therefore suitable for use in distance education.

Much of the research on approaches to studying has considered at micro level outcomes, such as the depth of understanding of an academic article. Marton and Saljo (1976a) found a clear relationship between a deep approach and a deep level of understanding in such tasks. Svensson (1977) argues that the relationship is inevitable rather than statistical.

Some studies have examined the relationship between approaches to studying and macro level output variables of academic performance. Svensson (1977) related students' approach to learning in an experiment with their normal approach to study by an interview question. Only 23% of the students classified as surface learners in both experiment and normal study passed all examinations. However 90% of the students classed as deep learners in both passed all examinations.

Ramsden and Entwistle (1981) examined the relationship between approaches to studying and self-reported ratings of academic progress. Discriminant function analysis was conducted to discriminate between those who believed they were doing very well and those who believed they were doing badly. Organized study methods, positive attitudes to studying, and a strategic approach were the variables which best defined the function. The authors themselves, Entwistle and Ramsden (1983), have recognized the limitations of this approach in that the analysis of self reported performance against other self assessments of learning, leads to a degree of circularity which may account for the correlations observed.

Watkins (1982) reports a study of the relationship between approaches to studying and academic grades awarded. This study found that disorganized study methods, surface approach and negative attitudes to studying were consistently related to academic performance.

Harper and Kember (1986) drew the distinction between performance, as an academic outcome, and persistence. Arguing that academic grades from fail to high achievement were not a reliable uniform measure of performance, they considered the difference between high achievers and those who barely passed their course. In the case of external students, having positive attitudes to study, organized study methods and a strategic approach are the best predictors of high achievement. For internals however, students who do not globetrot and display high levels of academic motivation are the most likely to succeed.

Distance education has long been concerned with the magnitude of drop-out rates from its courses. It is appropriate then to consider the relationship which might exist between approaches to studying and this all important outcome variable.

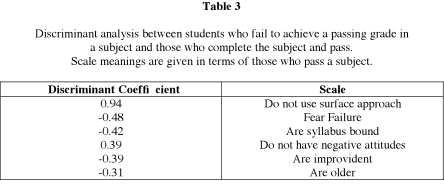

Kember and Harper (1986) used discriminant analysis to distinguish between distance education students who completed the subject they were studying and obtained a passing grade (persisters) and those who did not (non-persisters). The results of the discriminant analysis are shown in Table 3.

The variable which most strongly discriminates between the persisting and non-persisting group was surface approach. The implications of this finding will be discussed in the next section.

The second variable to appear in the stepwise analysis was fear of failure. Presumably students are dissuaded from withdrawing because of their fear of appearing to have failed to obtain the qualification enrolled for.

The fact that syllabus-boundness discriminates against persistence may indicate that truly independent students find external courses either too prescriptive or lacking in choice. Gibbs (1984) has expressed the view that the typical Open University format may be too ordered and too prescriptive for independent students. Because of the resources needed to develop good quality distance education course materials, the choice of units within courses is often limited. Also it is unusual for students to be offered alternative paths within units. The mature distance education student may desire a program relevant to career needs (Knowles, 1984, p. 31) which implies choice from alternatives unless the student group is completely homogeneous - an unlikely possibility.

The fact that older students are more likely to persist is consistent with the finding that older students are more likely to display a deep approach (Harper & Kember, 1985). They are more likely to be interested in the subject matter for its own sake, to search for the key concepts and to relate them to their own experience. Such a meaning orientation must be more fulfilling than rote learning; so propensity to withdraw is reduced.

The previous section has discussed the relationship between the approaches to studying process variables and output variables. The remainder of this paper looks at the way in which the students' approach to academic tasks can be influenced by a number of input variables such as curriculum design, instructional design and the nature of assessment.

Surface approach has been shown to be the variable which is most strongly linked to output measures, so the discussion centres on the way in which input measures can influence this variable. If the measures can dissuade students from making excessive use of the surface approach then there should be an effect on output variables too. A reduction in the number of students employing a surface approach also has intrinsic merit.

As surface approach was the approach to studying variable which most strongly discriminated between persisters and non-persisters, it is reasonable to suggest that withdrawal rates might be reduced if distance educators were to succeed in orienting their students away from a surface approach. Such an initiative has appeal because it not only offers the prospect of increasing pass rates but is also consistent with the traditional goals of tertiary education. Graduates from tertiary institutions, surely, ought to have abandoned habitual rote learning in favour of more meaning-orientated learning styles.

Programs attempting to orientate students away from a surface approach are therefore doubly attractive. However such initiatives appear to require a comprehensive approach. Two main aspects need to be addressed. Firstly there are students who habitually employ a surface approach to tertiary studies in subjects which require a deep level approach. They need study skills assistance to develop the capability of appropriately utilizing a deep approach. There are also students who would normally make appropriate use of the deep approach but because of factors such as surface assessment demands, high workloads, over prescriptive courses or an inhospitable learning environment, resort to a surface approach. This second problem can only be ameliorated if the factors influencing students towards a surface approach are addressed by curriculum design, instructional design or institutional policy.

If a study skills program is to teach students the skills needed for a deep approach and teach them to employ that approach as appropriate, it must be carefully formulated. Many traditional study skills courses contain sections on enhancing memorisation by techniques like rehearsal or mnemonics. Hypothetical graphs, showing memory decay with time, are used to reinforce the exhortations to constantly revise the material presented. Study skills programs with this type of content surely would tend to reinforce the notion that rote learning is appropriate for tertiary learning. Gibbs (1981, p. 61) has produced a damning critique of such study skills course which not only castigates proponents for these likely negative effects but also exposes the shallow research from which the memorization techniques are derived. While some of these techniques may have their place in the armory of methods available to the versatile student, one must be careful not to overemphasize their importance.

The alternatives to these traditional study skills programs are the metacognitive approaches to assisting students with their learning styles, which have been reviewed by Ford (1981).

Baird and White (1982) assert that learning will be improved if the learners are trained in processes of self-evaluation and decision making so that they can be aware of the process and nature of their learning. Gibbs (1981) maintains that advice on study methods is insufficient as students need to spend a period of time actively examining both the content and processes of their learning.

Students who are able to employ a deep approach will still employ a surface approach if a deep approach does not seem to be demanded, goes unrewarded or is difficult to achieve in a hostile learning environment. Neither approaches to studying nor learning styles are fixed and immutable. Students adapt their approaches according to the content and the context of the learning task (Fransson, 1977). There are a number of results in the literature which show how students can be influenced towards a surface approach. These findings will be presented in turn and the implications for distance education discussed.

Marton and Saljo (1976b) asked two groups of students to read a series of three articles. After each reading one group was asked questions on the underlying meaning of the article, the other group was asked about factual detail. Students in the latter group who habitually employed a deep approach had tended to adopt a surface approach in the face of persistent factual questions. However surface learners who were asked meaning- orientated questions did not adopt a true deep approach but tried to remember summaries of the author's arguments without actively examining them. The conclusion derived from the experiment was that a surface approach was easy to induce with factual questions whereas persuading surface learners to adopt a deep approach was not an easy task.

Distance education study materials often use in-text or adjunct questions as mathemagenic activators (Rothkopf, 1965, p. 198). There are a number of guidelines for their use based on research into the effect of inserted questions on learning from reading tasks (e.g., Kember, 1985). The work of Marton and Saljo (1976b) should also be taken into account when using in-text questions. If the questions consistently ask for nothing more than the recall of factual information presented in the study guide or textbook, then students might reasonably assume that the course demands memorization of details and resort to rote learning. If higher order skills such as application, analysis, synthesis or evaluation are really desired, then at least some of the questions in the study guide should demand responses which require students to use those same skills.

In a study of first-year economics students (Dahlgren, 1978; Dahlgren & Marton, 1978), it was found that few students had truly grasped the technical meaning of basic concepts by the end of the course. Dahlgren (1978) related the lack of understanding to the overwhelming nature of the curriculum. Faced with the large quantity of knowledge students tended to abandon the search for meaning and resorted to memorizing algorithmic procedures for answering problems in order to pass examinations.

Ramsden and Entwistle (1981) related the results from a large survey of students using the Approaches to Studying inventory to the students' perceptions of the teaching in their departments. It was found that departments which scored highly on good teaching allowed freedom in student learning and did not impose excessive workloads had a higher than average proportion of students who displayed a meaning orientation.

Excessive workloads may have a magnified impact on part-time distance education students who are only able to devote a limited proportion of their time to study. Distance educators should therefore be particularly zealous in seeking out units which impose an unreasonable workload. The research evidence suggests that reducing the content of overloaded courses should result in an increase in the quality of learning even if the quantity of factual material covered is reduced.

A decrease in factual content for many courses should be of little concern since information is becoming outdated at an ever increasing pace. Rather than attempting to build a knowledge base, courses might concentrate on teaching students to be independent learners of the subject so that they can keep themselves abreast of subsequent developments.

As reported in the previous section, the Ramsden and Entwistle (1981) study found that a meaning orientation was associated with freedom in student learning as well as reasonable workloads. Fransson (1977) found that students are likely to use a surface approach when they have little interest in the subject matter or do not perceive its relevance to their needs.

The provision of freedom of learning and courses relevant to student needs implies flexibility and a range of options within courses. Distance education courses frequently offer less flexibility and less options than face-to-face teaching. It is easy to negotiate individual study paths with on- campus students as long as there is a reasonable staff/student ratio. However the provision of flexibility within distance education units requires extra investment in producing a package of study materials with optional streams and higher levels of academic support to mark the diverse assignments and tutor the options. Providing a wider range of units within a distance education course also requires considerable investment; the initial expenditure in producing good quality distance education course materials is high.

It seems highly unlikely that funding will be provided for institutions to develop extra units to increase the flexibility of their courses. Reductions in real funding seem more likely. The Open University is currently under pressure to reduce the range of its offerings (Duke, 1986). An increase in the range of units available is therefore only likely to occur if institutions cooperate and accept or offer units developed by other institutions.

This paper has reviewed the emerging and rapidly expanding literature on approaches to studying and student learning styles. The literature has been shown to be relevant to distance education.

Of the constructs derived from this body of research, surface approach appears to be the one most strongly associated with the failure of students to complete their course of study. Students who employ a surface approach fall into two categories. There are those who habitually employ a surface approach and need study skills training to develop learning styles more appropriate to tertiary education, and there is a second category of students who are capable of employing a deep approach but use a surface approach for a variety of institutionally dependent reasons.

The research indicates that the propensity of students to resort to a surface approach can be reduced by ensuring that questions and examinations demand a deep approach, workloads are reasonable and courses have sufficient flexibility to offer relevance and induce intrinsic interest. Any initiatives along these lines would be in keeping with the desire to produce graduates who are true independent learners as well as to reduce the use of a surface approach.

Research on full-time face-to-face students has revealed a number of variables which influence the way in which students approach their academic tasks. There are many distance education variables which have not been investigated which may have an influence on students' approaches to study. It is possible that research into links between approaches to studying and variables such as instructional message design, provision of tutorials or residential schools, quality of assignment feedback or the instructional design approach might reveal many more ways in which the students' approaches to studying can be modified.

Baird, J.R. & White, R.T. (1982). Promoting self-control of learning. Instructional Science, 11, 227-247.

Biggs, J.B. (1978). Individual and group differences in study processes. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 48, 266- 279.

Biggs, J.B. (1979). Individual differences in study processes and the quality of learning outcomes. Higher Education, 8, 381-394.

Dahlgren, L.O. (1978). Qualitative differences in conceptions of basic principles in economics. Paper read to the 4th International Conference on Higher Education at Lancaster, August/September, 1978.

Dahlgren, L.O. & Marton, F. (1978). Students' conceptions of subject matter: An aspect of learning and teaching in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 3, 25-35.

Duke, C. (1986). The Open Unviersity - The next sixteen years. Open Learning, 1(2), 45-47.

Entwistle, N.J. & Ramsden, P. (1983). Understanding student learning. London: Croom Helm.

Ford, N. (1981). Recent approaches to the study and teaching of effective learning in higher education. Review of Educational Research, 51(3), 345-377.

Fransson, A. (1977). On qualitative differences in learning. IV - Effectives of motivation and test anxiety on process and outcome. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 47, 244- 257.

Gibbs, G. (1981). Teaching students to learn: A student-centred approach. Milton Keynes: The Open University Press.

Gibbs, G. (1984). Better teaching or better learning. HERDSA News, 6, 1.

Harper, G. & Kember, D. (1985). Learning styles of students in two distance learning institutes. Paper presented at the 13th world conference, International Council for Distance Education, Melbourne.

Harper, G. & Kember, D. (1986). Approaches to study of distance education students. British Journal of Educational Technology, in press.

Kember, D. (1985) The use of inserted questions in study material for distance education courses. ASPESA Newsletter, 11(1), 12- 19.

Kember, D. & Harper, G. (1986). Approaches to learning and academic outcomes. Paper presented to the 12th annual HERDSA Conference, Canberra.

Knowles, M. (1984). The adult learner: a neglected species. Houston: Gulf Publishing Company.

Marton, F., Hounsell, D. & Entwistle, N. (1984). The experience of learning. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press.

Marton, F. & Saljo, R. (1967a) On qualitative differences in learning, outcome and process I. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 46, 4-11.

Marton, F. & Saljo, R. (1976b) On qualitative differences in learning, outcome and process II. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 46, 115-127.

Morgan, A., Gibbs, G. & Taylor, E. (1980). The work of the study methods group (Study Methods Group Report No. 1). Milton Keynes: The Open University. Institute of Educational Technology.

Nie, N.H., Hull, C.H., Jenkins, J.G., Steinbrenner, K. & Bent, D.H. (1975). SPSS statistical package for the social sciences. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Pask, G. (1976a). Styles and strategies of learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 46, 128-148.

Pask, G. (1976b). Conversational techniques in the study and practice of education. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 46, 12- 25.

Pask, G. & Scott, B.C.E. (1972). Learning strategies and individual competence. International Journal of Man-Machine Studies, 4, 12-25.

Ramsden, P. (1983). The Lancaster approaches to studying and course perceptions questionnaire: Lecturers' handbook. Mimeograph, Educational Methods Unit, Oxford Polytechnic.

Ramsden, P. & Entwistle, N.J. (1981). Effects of academic departments on students' approaches to studying. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 51, 368-383.

Rothkopf, E.Z. (1965). Some theoretical and experiemental approaches to problems in written instruction. In Krumboltz, J.D. (Ed.). Learning and the educational process. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Svensson, L. (1976). Study skill and learning. Gothenburg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis.

Svensson, L. (1977). On qualitative differences in learning. III - Study skill and learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 47, 233-243.

Watkins, D. (1982). Identifying the study process dimensions of Australian university students. The Australian Journal of Educaltion, 26(1), 76-85.