VOL. 21, No. 3, 59-92

Much has been written about the promise of online environments for higher education, and there is a rapidly growing body of research examining the nature of learning and interaction in such courses. This article presents a discourse analysis of an interactive, text-based, online, graduate education course, designed and taught according to constructivist principles. Qualitative analysis was used to describe the discourse devices and strategies that participants used in order to establish and maintain community, to create coherent academic discussions, and to negotiate agreements and disagreements over the length of the course. The results have implications for our understanding of how topical and social cohesion are established in online discussion, and demonstrate how participants use patterns of agreement and disagreement rhetorically to persuade and learn from others while also protecting the trust and inclusiveness of the online community.

On a beaucoup écrit sur la promesse des environnements d'apprentissage en ligne en enseignement supérieur, et le nombre de travaux de recherche traitant de la nature de l'apprentissage et de l'interaction dans ces cours ne cesse d'augmenter. Cet article présente une analyse du discours dans un cours gradué à base de textes, en ligne, conçu et enseigné selon des principes constructivistes. Une analyse qualitative a été utilisée pour décrire les stratégies de discours utilisées par les participants pour établir et maintenir une communauté, pour créer des discussions académiques cohérentes et pour négocier tout au long du cours. Les résultats ont des implications quant à notre compréhension de la façon dont la cohésion sociale est établie dans une discussion en ligne et démontrent comment les participants utilisent des formes d'accord et de désaccord rhétoriques pour persuader et apprendre des autres tout en préservant la communauté.

In recent years, online learning has become a common form of course delivery in higher education. As university courses go online, faculty have the opportunity to re-design their teaching to reflect the philosophical shift to social and cognitive constructivism that underlies much current thinking about best educational practices. Online course design also can capitalize on the affordances of Internet technology for fostering interactive, discursive, egalitarian, and critically-oriented learning environments. McDonald (2002) describes online distance education as “a force for change in higher education, extending and improving education in general” (p. 12).

Research into the nature and effectiveness of online courses examines the impact of these sweeping changes in distance education and provides guidance for online course designers. The study of discourse patterns in interactive online courses is one source of evidence of use to course designers, instructors, and students engaged in online learning contexts (Kanuka, 2005). The purpose of my research study is to identify and describe the discursive devices and strategies that participants in an asynchronous, interactive, text-based, university course used to establish and maintain community, create coherent academic discussions, and negotiate meaning.

In less than two decades, the availability, ease, and popularity of communication via the Internet has changed the nature of interpersonal communication worldwide. The medium of electronic communication, with its ability to transcend geographic distance, democratize access, and alter the constraints of time and materiality, is becoming a change force in higher education (Frank, 2000, McDonald, 2002), and, in particular, is revolutionizing distance education (Haughey, 2005a).

Many universities provide fully online delivery of specific courses or of entire university programs, and blended (or hybrid) offerings are even more common (Haughey 2005b). Universities utilize online offerings to serve hard-to-reach students in their traditional catchment areas, as well as to compete for new students worldwide. The technological medium offers affordances that provide new possibilities for teaching and learning, capitalizing, for example, on the technologically mediated shift to multimodal literacy (Jewitt & Kress, 2003). A number of researchers have argued that computer-mediated communication (CMC) in online learning can facilitate more egalitarian discussion and enhance critical thinking (Cooper & Selfe, 1990; Davis & Brewer, 1997; Jonassen, Davison, Collins, Campbell & Haag, 1995; Lapadat, 2004; McComb, 1994; Weasenforth, Biesenbach-Lucas & Meloni, 2002; Whittle, Morgan & Maltby, 2000). This has led to a philosophical re-visioning towards a constructivist approach to teaching and learning in online course design, which fits with current views of best practices in education (Doolittle, 1999, 2000; Gabriel, 2004; Gee & Green, 1998; Harasim, 1990; Molinari, 2004; Roschelle & Pea, 1999).

The shift to distance education delivery via the Internet in the context of a new, globally accessible, technologically mediated space for human interaction calls for concerted research examining the nature and effectiveness of online courses. As recently as 1998, Blanton, Moorman, and Trathen described the existing research as “philosophically and theoretically barren” (p. 259) and noted that there had been few studies examining discourse patterns in online communities. In response to this need, there are now many studies and journals focused on online communication. An area of promise is the study of online discourse patterns to provide data-based evidence of the nature of construction of meaning and social relationships within online environments (see work by Schallert and colleagues, 1996, 1999; as well as Colomb & Simutis, 1996; Conrad, 2005; Davis & Brewer, 1997; Enomoto & Tabata, 2000; Rose, 2004; and Stewart & Eckermann, 1999).

Discourse analysis is a qualitative approach drawn from linguistics and the field of communication studies, which involves the explicit analysis of spoken or written interactive language to examine the content, structure, and processes of human communication. Traditionally, this research approach has been used mostly to describe discourse and build theoretical models of discourse. However, as much teaching and learning is accomplished through discursive interaction, whether in face-to-face (F2F) or computer-mediated communication classes, discourse data provide evidence that can be used to trace the learning that occurred, examine the effectiveness of the teaching, or provide insight about the classroom or virtual environment.

In an early paper examining Interactive Written Discourse (IWD) in synchronous online dialogues, Ferrara, Brunner, and Whittemore (1991) define IWD as a newly emerging register with characteristics of both written and spoken language. They argue that online discourse communities are in the process of establishing conventions of use by drawing on their knowledge of existing genres and registers, and by learning from other users within the context of online interaction. Although synchronous and asynchronous online interaction differ in significant ways (Lapadat, 2002), both are newly emerging forms of written discursive interaction, and both offer opportunities to observe how participants implement discursive devices in a new communicative context and go about establishing conventions of use.

In my past research, I have utilized discourse analysis to examine teaching and learning in computer-mediated course delivery. In these studies, I have described the combination of speech-like and written-like elements that give online conversations a unique character (2000a, 2002), discussed how online transcripts provide a unique means of tracing and thus assessing learning (2000b), and argued that appropriately designed CMC environments can facilitate higher level thinking (2000a, 2000b, 2002, 2004). One study, focused on the first four weeks of an interactive online graduate course, looked at discursive content to identify students' initial positions on issues and the joint understandings they began to establish (Lapadat 2000a, 2003). I found that they developed a view of course topics as multidimensional and reflecting multiple perspectives, explored the idea that educational problems are political not just technical, and agreed that teachers have a limited scope of influence. Although the study traced the early emergence of shared perspectives, it did not examine the strategies students used for acknowledging, building on, and negotiating points of view.

Further study is needed to describe the discourse devices used in CMC to establish community (Haythornthwaite, 2005; Preece & Maloney-Krichmar, 2005), to increase coherence in online interaction, and to negotiate agreement. Haythornthwaite et al. (2000) defined the characteristics of community as including “recognition of members and nonmembers, a shared history, a common meeting place, commitment to a common purpose, adoption of normative standards of behavior, and emergence of hierarchy and roles” (p. 2). They showed that participants in online environments behave in ways consistent with this definition of community, and describe a feeling of belonging to the virtual communities in which they participate.

Brown (2001) described the characteristics of online communities similarly, mentioning aspects such as shared purpose, joys, and trials; a sense of belonging and connection with others; a climate of caring; good communication; and continuity (p. 20). From interviews with graduate students taking online courses, she concluded that “commonality [is] the essence of community” (p. 22), and that interaction is central and necessary for the development of community. She described a three-step process through which online community evolves: (a) forming acquaintanceships or friendships online; (b) community conferment or membership, which comes about through engagement in long threaded discussions; and (c) camaraderie, achieved through long-term and intense personal association and communication.

Like the theorists mentioned above, Rovai (2001, 2002) has suggested that geographical closeness is not an essential characteristic of communities. He defined community as: “mutual interdependence among members, connectedness, interactivity, overlapping histories among members, spirit, trust, common expectations, and shared values and beliefs” (2002, p. 42). In a study of educators participating in an online post-degree course employing multiple formats and tools, Rovai (2001) found that only 20% of messages showed a connected pattern, and that female participants were more likely to use a connected pattern. In another study comparing F2F and CMC classes across 14 graduate and undergraduate courses at two universities, Rovai (2002) found that students' perceptions of degree of community, as measured by the Sense of Classroom Community Index, were not significantly different in the F2F and CMC contexts. Both studies suggest that the formation of community online may be particularly sensitive to pedagogical approach, and to the type of interactive climate fostered by the instructor.

Conrad (2005) explored the development of community among graduate students enrolled in a multi-year online program. She found that, over time, their definition of community shifted from the external dimensions of time, space and action to a relationship-based construct. Their descriptions emphasized connectedness, and referred to experiences of “comfort, familiarity, dependence, tolerance, and ease” (p. 14), and feelings of “sharing, caring, belonging, and support” (p. 14).

In a commercial rather than higher education context, Boyd (2002) considered the claim that “community is the basis of trust and safety” (p. 8) in the eBay environment. He describes seven elements that enable the eBay community to function as a safety net: individual, traceable identities; the use of a common symbol system or jargon; the opportunity for reciprocal influence; a shared narrative; an emotional connection; antagonism towards those who have violated the community's rules; and the use of status markers (which can be earned). Although eBay is a particular environment that differs from the environment of an online university course, both online contexts function best if there is a sense of shared purpose, trust, and safety (see Gabriel, 2004). Researchers examining CMC courses have observed that an online community does not form unless there is a sufficient number of engaged participants, and that many factors (perceived instructor absence; instructional approach; optional nature of the online forum; unclear expectations about online collegiality; few opportunities for social communication) can obstruct the formation of community (Barab, MaKinnster, Moore, & Cunningham, 2001; Brown, 2001; Kanuka & Anderson, 1998; Lapadat, 2000a; Rovai, 2001).

Researchers have begun to describe specific discursive aspects of online interaction that promote a sense of community (Kanuka & Anderson, 1998; Haythornthwaite et al., 2000; Rose, 2004; Stacey, 1999). For example, Rourke, Anderson, Garrison, & Archer (1999) described three categories of responses in online conferences that contribute to a sense of social presence: (a) affective responses (including expressions of emotion, use of humor, and self-disclosure); (b) interactive responses (including continuing a thread, quoting from others' messages, explicitly referring to content of other participants' messages, asking questions, complimenting or conveying appreciation, and expressing agreement); and (c) cohesive responses (including use of others' names, addressing the group as “we” or “us,” and using language for a social function) (p. 61). By counting and calculating proportion of use of these devices in selected segments of online courses, they postulated a measure of social presence density.

Murphy and Collins (1997) also examined the emergence of communication conventions in a graduate online course, but in a synchronous modality. In ranking the frequency of use, they found that the most used conventions were: “sharing information or techniques for conveying meaning and indicating interest in a topic, using keywords and names of individuals, using shorthand abbreviations, questioning and seeking clarification, and … greeting each other and referring to each other by name” (p. 177).

Coherence of online communication is also an important issue to consider in using CMC in distance education. Discourse coherence refers to the communicative partners' perception that the conversation “holds together,” that subsequent contributions build on earlier ones, and that overall it makes sense. Although there is not any broad framework that has been widely accepted by linguists as an adequate model of discursive coherence, some components of it have been studied extensively in spoken conversation, such as turn-taking patterns, adjacency pairs, intonation markers, backchannel feedback, and semantic cohesion. In electronic communication, Herring (1999) argued that CMC presents an incoherent conversational environment, but said that users are able to adapt in spite of this. Both synchronous and asynchronous CMC lack cross-turn coherence; in contrast to spoken interaction, IWD has a “lack of simultaneous feedback … [and] disrupted turn adjacency” (p. 3) which lead to violations of both turn-taking norms and sequential coherence. Herring described some of the adaptations and devices that users implement to compensate: backchannel remarks, turn-change signals, addressivity (use of names), linking (explicit back-referencing), and quoting. She also noted that appropriate design of the discussion environment (e.g., by assigning topics, or supporting threading), and the existence of a persistent textual record reduce fragmentation as well. She suggested that some participants may use the loosened coherence to advantage to intensify online interactions and promote language play.

Schallert and her colleagues also have examined the nature of coherence in CMC classroom discussions (1996, 1999). They noted that “theorists … have described coherence as a psychological response of individuals as they make sense of discourse, a sense of continuity and of 'right fit' that they can construct from the language they are processing” (1996, p. 473). Schallert et al. (1996), espousing a socioconstructivist perspective, extended this notion to include the ways coherence is constructed within communicative exchanges of a discourse community.

Specifically, they compared coherence in synchronous CMC and oral graduate seminars. Like Herring (1999), Schallert et al. (1996) acknowledged the apparent chaotic structure of CMC transcripts, as contrasted with the orderly progression of topics and the cohesion of adjacency pairs in oral discussion. They used coherence graphs to reconstruct topic development in the written electronic discussions that they studied (1996, 1999), showing that, despite violating the sequential turn-taking of oral conversation and their chaotic surface appearance, synchronous online discussions are coherently structured, and this coherence is perceived by the participants. They noted that this coherence is facilitated by participants' use of explicit reference markers (1996; also see Honeycutt, 2001). Also, they pointed out that “even when surface indicators of cohesion were absent, participants in the written discussions were able to construct a coherent conversation. The high degree of felt coherence reported by participants in the oral discussions was in part due to a willingness to see utterances as connected” (1996, p. 482).

In contrast to the study of community formation and coherence structures in online learning environments, discursive strategies for negotiating agreement and achieving shared understandings have received little explicit attention. Kanuka & Anderson (1998) argued that social discord within online forums may provide an important catalyst for the social construction of knowledge. However, Granville (2003) pointed out that instructional approaches that promote critique can stir up conflict that results in a hostile and nonproductive learning environment. She talked about “the necessity for creating a 'safe space'” (p. 13). Discursive agreement and disagreement patterns, therefore, are an interesting focus for analysis, as they provide an insight into rhetorical strategies and debates about meaning, as well as participants' strategies for negotiating different perspectives without impairing the online community.

This case study of an online graduate course employs discourse analysis to examine the computer-mediated communication within the course conference. Specifically, the analysis identifies discourse devices used by participants to establish community and create coherence, as well as their discursive patterns of negotiating agreements and disagreements.

Participants included six graduate Education students (five women; one man) from four different Canadian communities, and the instructor (the current author and co-designer of the online course). 1 The seminar-style course, which centered on asynchronous threaded discussions, was interactive, text-based, and entirely online, except for the readings, distributed through the university library, and written assignments, which students mailed to the instructor. This required graduate-level course on the topic of “Discourse in Classrooms” also was taught regularly in the F2F modality by the same instructor. Although all these students previously had used computers for word-processing and e-mail, they varied in their comfort level and amount of experience with computers. Most had taken distance courses in the past, but none (other than the instructor) had participated in an online discussion-based course before. Three students knew each other from a F2F course with the same instructor the previous semester, two others knew only the instructor from previous courses, and one was new to the program.

The full transcripts of the forum discussions over the thirteen week course constituted the data. These were saved as a chronological text file, 293 pages in total. Each contribution to the online forum was imported as a separate numbered document into NVivo qualitative analysis software (Fraser, 1999; Richards, 1999), retaining name of the sender, date, time, the subject (the instructor/designer assigned each weekly topic a subject name), and a subtopic (topic header assigned by the writer of the message). There were 357 contributions (documents) in all, ranging from one-line comments to multi-page compositions. The conferencing software2 allowed posts to be read chronologically, grouped according to the weekly subjects, or by following emergent discussion threads. All topics in the forum remained available and active throughout the course.

In this analysis, I examine two categories of devices—those for establishing and maintaining community, and those cohesive ties that participants utilize to create a sense of coherence in the online discussions3. The method of analysis involved the use of inductive coding through iterative rereading and constant comparison. As each particular device came to notice through a process of reading and rereading the chronological transcript, I labeled it. Each device category was further refined through a process of constant comparison, looking back as each new instance was identified. This coding and analysis was facilitated through the use of NVivo qualitative analysis software and its sorting tools. In the final portion of the analysis, I look at broader patterns of meaning negotiation across the length of the course, specifically tracing examples of agreement and disagreements across participants. For topic initiations that elicited statements of agreement or disagreement, this involved then tracing every subsequent contribution to that topic and describing the discourse strategies used.

Devices for Building and Maintaining Community

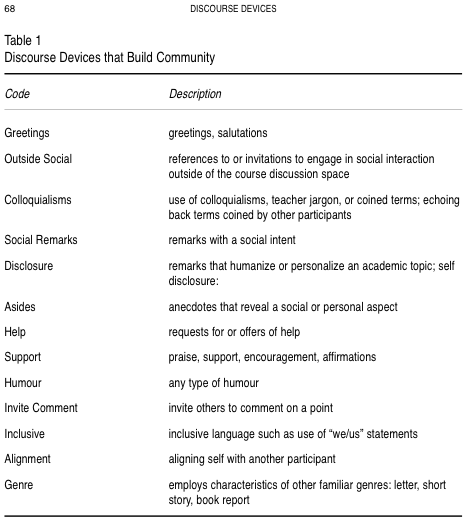

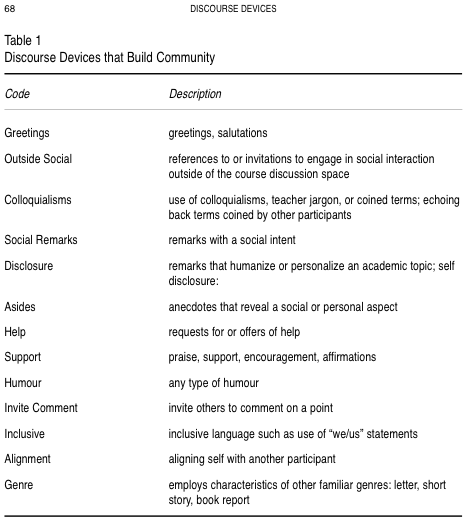

Through the process of inductive coding as described above, thirteen discourse devices that promoted the development of community were identified. These were: the use of greetings, references to social situations outside of the course, the use of colloquialisms and teacher jargon, social comments, self-disclosure, anecdotal asides, requests for or offers of help, supportive remarks, the use of humor, invitation to comment, the use of inclusive language, alignment, and the use of familiar genres (see Table 1). It is clear that community-building discourse devices used by the course participants include many of the strategies mentioned by Rose (2004), Rourke et al. (1999), and Murphy and Collins (1997). These strategies can be seen as community building in that they introduce personal elements into to the discussion, promote inclusion and a feeling of safety, and give participants a sense of ownership of the topics. An important observation is that there were no instances of “flaming” in these data. Participants avoided using derogatory or negative personal remarks. Although they did disagree with each other, they were careful to frame these disagreements in ways that would not impair the sense of online community, as I discuss subsequently.

Greetings. Participants frequently began their message with a greeting. These included greetings to the group at large, such as “Hi everyone,” or “Hello fellow classmates!” as well as greetings directed to a specific member of the class, such as “Hey Rita.” and “Hi Judy.” 4 Greetings often were combined with social remarks or supportive comments, such as “Hi everyone, welcome to the class Patrick. Judy, I enjoyed your comments on the last topic;” “Hi Judy! Hang in there!” and “Hi Rita! I can just picture you standing in front of a bunch and making moo sounds. Anybody walk by?” Altogether, 40% of messages began with an explicit greeting. Rita and Elaine were especially frequent users of greetings, contributing 29% and 26% of the greetings respectively, with the rest of the class members contributing 7-12% of the greetings each, except for Professor, who contributed less than 3% of the greetings. In addition to these initial greetings, participants addressed each other by name within the body of messages.

Social remarks, invitations, and asides. Most remarks used for the purpose of socializing tended to be confined to the introduction or termination of the message, bracketing participants' more academically focused writing and adding a human touch. For example, Elaine ended one of her entries with: “Don't look at the spelling! IT'S 3 IN THE MORNING SO TAKE PITY!” An exception is the use of asides, which were just as likely to appear within the body of the messages. Participants tended to mark these explicitly by putting them in brackets, or by stating that the remark was a digression. As an example, Patrick begins an aside as follows: “[huge digression here….]” marking it both in text and with brackets. Asides were used for adding information, invoking a shared experience, commenting on process, making a social remark, relating a personal anecdote, or making humorous or critical remarks. For example, in describing the challenges of collecting data, Judy references a frustrating research experience that Rita previously had shared, in which Rita had videotaped a family who were seated in front of a bright window. Rita's subjects were conversing about hockey and the Zamboni ice cleaning machine. Judy writes: “In my video recording I shot the back of my subjects' heads so I couldn't see their facial expressions. (Rita knows this problem well from the zambonie tapes!).” Invitations to engage in interactions outside of the group conference, or references to past interactions of this type were rare, and were mostly used by Rita and Elaine, who lived in the same community and met with each other on occasion.

Help, support, humor, and invitations to comment. Requests for help or invitations to comment, although infrequent, almost always were taken up by at least one other participant. Humorous remarks and comments that praised, supported, encouraged, or affirmed others' remarks and experiences were used frequently by all of the participants throughout the course. For example, Colette wrote: “Lisa, I just loved your comments. You made me smile. It sounds like you have a gift for people warming to you and trusting you.” It is likely that such types of comments contributed to the participants' perceptions that the online interaction was enjoyable, and felt safe.5

Genres and colloquialisms. The style of writing that participants used in their messages ranged from a formal academic style of writing to informal chat. Writing was most formal in the students' article presentations. This was an online assignment, in which students reported on a journal article they had chosen and read, and then others in the class responded. These written contributions were quite long, and borrowed characteristics from the book report type of genre. Formal writing also tended to be used for initiating contributions on a new weekly topic, then once others began to respond, the writing became more interactive and informal.

Characteristics from other written genres that sometimes were apparent in the style of writing included the letter genre (e.g., beginning “Dear Rita,” or signing at the end with one's name), and the short story genre (e.g., Judy titled an anecdotal contribution, “A Sad Science Story”). The appearance of elements from different genres is interesting in that it shows shifts in how writers were construing their audience as they composed their messages. The presence of these examples also supports Ferrara et al.'s (1991) idea that IWD is a register under construction.

Aside from the contexts described above in which writing was quite formal, participants tended to use colloquialisms and teacher jargon throughout their messages. Examples are: “cooperative learning junky; lip service; hit the nail on the head; band wagon; soap box; reality check; yikes; how to's; pendulum swing; get a handle on; la la land.” The use of these terms gave the discussion a conversational feel, approximating the type of discourse used in F2F seminar discussions, and contributing to the sense that one was part of the group.

One interesting phenomenon was that, at times, a term that one participant would use or coin would be taken up by others in the course and be used over and over, eventually coming to stand for a key theme or issue of concern to the group. An example is the term right answer, initiated by Rita to refer to teachers' use of test questions (knowledge testing questions for which the teacher already knows the answer, rather than true information seeking questions). As the discussion evolved, it came to stand for the broader idea of resistance to change in education, as represented by transmission-oriented teaching, testing and the accountability movement, administrative rigidity, and teacher powerlessness. This process of echoing back and building on a coined term or “hot button” phrase was a powerful way of acknowledging another participant's views.

Inclusive language, alignment, and disclosure. In addition to the use of colloquialisms, three other devices seemed to especially contribute to the feeling that the class was an inclusive community: inclusive language, alignment, and disclosure. Participants used the pronouns we and us both to refer to the online group narrowly, as when Rita said: “We certainly found out that using descriptive tools is a little more difficult than it appears, in our last course,” and more broadly to refer inclusively to the online course members as part of the wider community of educators. An example of this broader sense is seen in Colette's remarks: “I chuckled at your comment vis a vis 'endless studies'. How can we take all social, political and cultural factors into account? … Guess we'll all bbe life-long readers, eh?” Professor used this device to position herself as a class member, to counter her given role as the authority and implicit one as Ivory Tower theoretician. In the following example, Professor uses we and explicitly marks its use: “In adopting the notion of approximations for our students, maybe we (generic “we”) need to be gentler with ourselves too in order to grow as teachers.”

Alignment refers to instances when a participant explicitly aligns with another class member by indicating that he/she shares the same point of view, or has had the same experience. An example is Judy's previous remark about Rita's Zamboni tapes. As another example, Colette said, “Like Rita, I use collaborative learning and discussion in the classroom.” The meaning of this statement can be understood with reference to the preceding discussion, in which class members have criticized traditional transmission-oriented approaches to teaching and proposed discussion-based approaches and cooperative learning as positive alternatives. Thus, by making this statement, Colette affirms Rita's previous contribution, aligns herself with the stance Rita has taken, and supports an emerging group point of view on teaching.

Throughout the course, participants frequently used anecdotes to personalize contributions and to reveal the practical implications of theoretical issues from their readings. Through this means, they made theory-practice connections, drew on their expertise as practitioners, expressed their own opinions, and turned the discussion to topics of immediate applied interest to them. For example, they related anecdotes about students they had taught, teaching approaches they had tried, or experiences their own children had had in school. This process of sharing experiences served to reinforce the sense of being part of a community.

As the course progressed, course members began to share more personal, emotional examples from their own experience. These self disclosures were an indicator that participants felt safe and acknowledged in this communicative environment. Also, by sharing embarrassing, humorous, and upsetting stories about themselves, participants showed a level of trust that deepened the bonds of this small community beyond the basic characteristics of community described by Haythornthwaite et al. (2000).

An example of this is a thread on the topic of math phobia. Rita initiated this thread with an inflammatory statement: “Sometimes I think math teachers (to pick on them) believe that unless you follow the religion of math you really are not a person.” Patrick leapt to the defense of math as an important subject and suggested: “I wonder if math anxiety is transmitted by elementary and secondary instructors who are math phobic?” Beneath the denotative meaning, this could be read as a veiled criticism of Rita, who is a secondary teacher. Lisa then posted a message that agreed with Patrick about the importance of math, and agreed with Rita in criticizing the way math is often taught, and suggested that the problem resides in requiring teachers who have little background in math to teach the subject despite their lack of training. She described herself as having been put in this position. Effectively, she mediated the potential discord in a way that was face-saving for both Patrick and Rita by pointing to systemic causal factors rather than personal ones, and also disclosed her own status as an under-prepared math teacher.

This introductory discussion about math initiated another series of contributions in which participants in the course disclosed that they were math phobic. Rita began: “Hi Patrick, perhaps I am a math phobic - it is certainly an area I struggle with. I'm afraid I don't have that kind of logical depth.” She went on to describe her past difficulties with math. She also apologized for her earlier inflammatory statement and agreed with Patrick that math is important. Then Professor described herself as not liking math during her early years of schooling because it was taught using a “skill & drill” approach. Judy built on this theme by describing herself as “terrified of science” and disclosing pressures in her home situation that exacerbated her self-perceptions. Colette contributed the observation that she always struggled with math, and provided a long anecdote about her experiences with math in school. Elaine jumped in and aligned herself with the math phobics: “I too am one of the ones who has missed the boat on math. For many years I have considered it my weakneess, my inability to see or underatand mathematical relationships or patterns.” Judy then wrote: “I must confess that I hate math. I can't even do a simple caculation without my calculator. I think I have math phobia!” She went on to describe her current difficulties in a statistics course. Elaine responded: “Hi Judy! Hang in there! Like you, my understanding of math leaves much to be desired … Lots of people have trouble with math but Dr. P. M. will get you through stats. … Keep your chin up!! Have you tried forming or joining a study group?”

Summary. The evolution of this discussion on math shows that participants felt comfortable enough in this online community to disclose quite personal details. The disclosures enabled participants to establish common ground and to offer support and understanding to each other. In tracing their discursive moves more broadly, it is evident that the participants worked to soften disagreements, deflect blame from individuals to external systems, align themselves with another member who was being criticized, and keep everyone included. They used many discourse devices to do this, including social greetings, remarks, and references; inclusive language, insider colloquialisms, and familiar genres; personal anecdotes and disclosures; alignment remarks; offers of help or support; invitations to comment; and humor. In summary, these data show evidence in a variety of ways that a community had formed via the online interactions in this course, and that class members valued their participation in this community.

Devices for Achieving Discursive Coherence

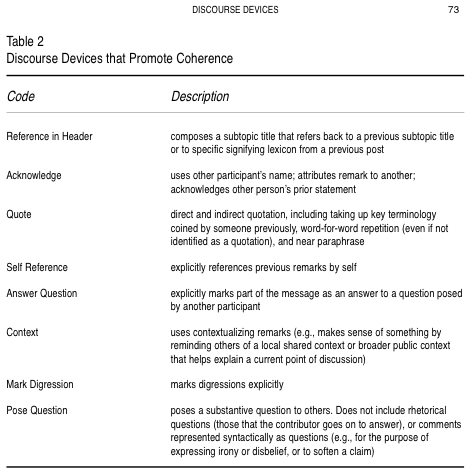

In this section of the article, I discuss the participants' use of devices that promoted coherence in the discourse. Following Schallert et al. (1996, 1999), I was interested in tracing discursive elements that contribute to coherence within online seminar discussions (although asynchronous here, rather than synchronous) because of the insight this provides into the nature of social construction of meaning. Herring (1999) has

documented that CMC participants do employ devices and strategies to enhance conversational coherence. As there are multiple paths through the posted messages, participants cannot assume that others share the same context (i.e., have just read the same remark), so they have to invent ways to mark cohesive ties back to earlier remarks. To understand how meaning is being constructed, these ties warrant detailed description and empirical examination. In the present study, I view discourse coherence as based in the set of discursive devices that course participants used to establish connections between their current message and previous or future online messages (see Rose, 2004). As with the previously described community-building discourse devices, the categories in Table 2 have emerged inductively through coding the online course transcripts, thus are grounded in these data.

I consider three types of devices that promote coherence: (a) backward reference (including use of reference in the subtopic header, acknowledgement of another participant's remark, quotations, self-reference, and answering of questions); (b) endogenous devices (including the use of contextualizing remarks, and marking digressions), and (c) forward structuring (posing questions to others). Backward reference includes explicit references back to others' or one's own previous remarks. Such references are explicit in that they point directly to previous text (e.g., Lisa writes: “In response to Elaine's review of Eder (1982)”), repeat the segment of previous text word for word as a direct or near quote, or use a signifying coined term (e.g., right answer).

The two forms of endogenous devices that I coded (Context, and Mark Digression) both had the effect of structuring the message composition with reference to the wider discussion to enhance coherence. The use of contextualizing remarks, such as providing background information, helped readers make sense of the point under discussion. The practice of marking digressions explicitly, either textually or with punctuation, helped readers to separate supporting anecdotes from main ideas.

Finally, although many forms of contribution to a discussion (comments, jokes, and so forth) may have the effect of forward structuring, that is, of influencing what others will say next, these relationships typically only become visible in CMC transcripts by examining the explicit backward references, which show which topic initiations were, in fact, taken up. Posed questions are an exception in that they entreat others to address a specific claim or issue that has been framed by the message writer, so elicit cross-message coherence by directing the future direction of the discussion. 6

Examples of coherence devices. In these data, 84% of the messages employed at least one of the coherence devices described in Table 2. Many showed multiple instances and forms of coherence devices within the same message. In 58% of contributions, participants composed a subtopic title that referred back to a previous contribution. An example from Rita is: “Sub Topic: Lisa's comments wk 3.” This figure is quite high, considering that backward referencing would not be appropriate when introducing a new topic, such as when presenting an article to the class or writing the first contribution to a new weekly topic.

Nearly half of the messages employed a coherence device in the opening sentence of the message (48%). Professor was particularly likely to open her message using devices to promote coherence, as 36% of messages that had a coherence device in the initial text were contributed by Professor. For example, Professor begins: “Elaine, in commenting on Rita's presentation of the Wilkinson & Calculator article on effective speakers made the point that language is distributed across the curriculum.” Explicit acknowledgment of this sort, as well as use of direct quotations, had the effects of pointing back to earlier topics and contextualizing the next points in the message.

As mentioned earlier, key terminology coined in some contributions was taken up by class members at large and became persistent theme markers throughout the course. An example of this is the “right answer” thread initiated by Rita (see Appendix A). As can be seen in these selected excerpts of the discussion, the term right answer came to stand for and represent the intersection of several key ideas being discussed in the course. One of the ways that class participants linked ideas to show their relationship was by invoking that specific term. It was also a way of affirming previous contributions by others on that topic, and making explicit how their points built upon the earlier points by others, thus serving both to build community and enhance coherence.

Summary. Participants in this online seminar employed many strategies and devices to enhance the coherence of the discussion. The online discussion felt coherent to participants, and, as I have shown here, the course transcripts reveal highly evolved discussion processes with coherence devices operating at multiple levels. Some processes of structuring that enhance coherence in oral discussion, such as multi-channel information flow and turn sequencing, were not present to the same degree in this online environment. However, it also can be argued that such means of imposing coherence might arise due to the linearity of oral communication; that is, they are adaptations to the oral medium rather than necessary correlates of coherence in argumentation. Although IWD has some speech-like qualities, it is a written medium with different constraints and referencing possibilities. Many coherence devices in these data seem to be drawn from written conventions for argumentation rather than oral ones. For example, the extensive use of quotations to make intertextual references resembles conventions used in academic writing. The technique of bracketing asides is a common practice in personal letter writing, as well as in email messaging. In sum, we need to re-evaluate claims that online written discussion is incoherent simply because it is different than oral discussion.

Negotiating Points of View: Agreements and Disagreements

As described above, participants in this course used discourse devices to support, include, and acknowledge others, thus enhancing community and providing a safe communication environment for the expression of opinions. Participants also employed complex strategies for agreeing and disagreeing over long segments of discourse. In these data, 47% of contributions included explicit statements of agreement with points previously made by others, which contributed both to community building and to the coherence of the online discussion. However, participants also were willing to express disagreement; 19% of contributions explicitly stated disagreement with others' remarks. Neither agreements nor disagreements tended to stand alone. Rather, a statement of either typically elicited a series of contributions from others indicating whether they disagreed or agreed with the original point or with someone's response to that original point.

Furthermore, as was seen in the previous math phobia example, the agreements and disagreements were complex, interwoven, and multi-purposed. For example, earlier agreements and disagreements tended to keep resurfacing throughout the course. In the case of a disagreement, the originator of an argument with which others had disagreed might try to convince others of his/her earlier claim by reintroducing it within the framework of a different, already agreed-upon topic, and arguing that the earlier disputed claim was, in fact, a subset of the agreed-upon issue. Similarly, a participant who disagreed with a stated perspective might keep coming up with new examples in an attempt to re-educate the originator. Also, contributions seldom expressed simple agreement or disagreement. Rather, a participant might agree with part of a previous point, disagree with another part, and add a different slant to the argument as well.

Through their pattern of agreements, participants explicitly established and made visible a body of shared understandings. By contributing examples from their different personal and educational contexts, they extended and deepened these shared understandings and beliefs. Agreements also enhanced the sense of being a cohesive community that shared experiences and values.

Their usage of disagreement seemed to accomplish different ends. For one thing, it established the online forum as a place for critical intellectual discussion, as contrasted with a place for uncritical acceptance of transmitted truths. Because participants were discussing topics that were deeply important to them, they had strongly-held beliefs about some issues. That disagreements were apparent in the transcripts shows that participants felt empowered to express their individual points of view, rather than being silenced or obliged to express consensus. Disagreement patterns in these data are particularly interesting to examine because participants had to negotiate the challenge of acknowledging and responding to perspectives counter to their own, while maintaining the sense of community and support that had emerged among this group.

Interestingly, Patrick, the only male in the course, a college instructor, and a self-described “quantitative guy,” set off the first sequence of strong disagreements with two posts that were among his first substantive contributions to the forum. Appendix B presents a summary of how this disagreement evolved. Patrick made three points that Elaine, a resource teacher with special needs learners in an inner city school, immediately disagreed with: that teachers should not have to tolerate “deviant behavior,” that teachers do not have time to individualize instruction, and that disrespectful interpersonal remarks in his classroom of adult learners were the fault of peer culture.

In disagreeing, Elaine used the following strategies: she acknowledged Patrick's points and expressed understanding of his experience; she presented an opposite view explicitly; she supported her argument with logical arguments and examples; she blamed the situation on the wider issue of lack of resources rather than teachers (allowing Patrick to save face); she invited Patrick to respond; she expressed emotion (shock; dismay); she instructed Patrick on alternative ways to handle the situation using elementary school examples; she positioned herself as “not-knowing” with respect to teaching adults (allowing Patrick to save face); she appealed to Professor (the authority) for support; and she reiterated her key points in a separate post (for emphasis).

Subsequently, Professor contributed a message agreeing with Elaine (thus implicitly disagreeing with Patrick); agreeing with Patrick's smaller point that teachers lack time (thus softening her disagreement with Patrick); and positioning herself as not knowing all the answers (both allowing Patrick to save face and forestalling future appeals to herself as authority). Then Rita indicated agreement with Professor and Elaine (thus implicitly disagreeing with Patrick); and added that this approach to teaching is hard to adopt but worth it (essentially providing a “pep talk” to encourage Patrick to change his ways). Finally, in her next direct remarks to Patrick online, Elaine made a point of agreeing in detail with points Patrick made on a different topic (perhaps to repair any hard feelings that might have arisen due to her earlier strong disagreement).

Participants clearly were attempting to accomplish a number of things through their patterns of agreement and disagreement, and they had a sophisticated set of discursive strategies that they employed to accomplish their ends. It is possible that Patrick relished the role of initiator of arguments, as there are other extended arguments in these data that revolved around Patrick's strong statements. This kind of argumentative stance is typical of some traditional forms of scholarly debate, and may be gender-linked as a discussion approach preferred by males (Cooper & Selfe, 1990; Rovai, 2001; but also see Wolfe, 2000).

Patrick's statements also can be read within in the wider context of what is already known about others' points of view. For example, Professor, who has inordinate power because of being the course instructor, has explicitly represented her viewpoint as critical, constructivist, transformative, and qualitative. Her viewpoint, although in opposition to mainstream views, may be seen as the accepted view in the context of this course. Some participants may be attempting to present their own perspectives as being similar to Professor's, a strategic alignment that positions them as “good” students. This interpretation provides another way to view Patrick's disagreement; he is resisting authority (Professor's views), but also representing the status quo (accepted mainstream views). These strategies might enhance his visibility and power within the class. By arguing against Patrick's status quo and aligning themselves with Professor, some participants might be shifting their viewpoints toward a more change-oriented stance. Overall, through their patterns of agreement and disagreement, participants engaged in a balancing act that involved in establishing individual identity and points of view, while also demonstrating affiliation with the online community and cultivating a sense of inclusion.

Online discursive interaction yields a permanent record that enables researchers to trace social negotiation of meaning by examining discursive devices used by participants. This record is not a reconstruction in the way transcripts of taped talk-in-interaction are (Denzin, 1995; Korenman & Wyatt, 1996; Kvale, 1996; Lapadat, 2000c; Lapadat & Lindsay, 1999; Mishler, 1991). In CMC conferences, the interaction is accomplished textually, whereas transcripts are extracts and reconstructions of conversational interactions that omit or selectively summarize contextual and extra-textual information (Korenman & Wyatt, 1996). Text-based conversation online is a new type of discursive interaction that is different from face-to-face classroom discussion, needing examination as interesting in its own right (Lapadat, 2002; McDonald, 2002).

This analysis of the written trace of an online asynchronous graduate seminar showed that participants used a variety of discourse devices to build community, enhance coherence, and manage disagreements. Through the use of these devices and strategies, they were able to share meaning and establish a set of common understandings. These data revealed how participants negotiated divergent points of view while protecting the safety of the discussion space and the sense of community. Via personal disclosures, the stances they took on controversial issues, and their alignments with points of view expressed by others, participants positioned themselves with respect to their philosophical and political orientations toward education.

Over the course, participants changed some viewpoints and consolidated others. Particularly interesting were the participants' changing views on praxis, and on their own potential to influence colleagues and alter practice in their professional settings (Lapadat, 2003). Most participants moved from a predominantly reactive to a more proactive stance. This entailed clarification of their own roles within the educational enterprise, a process which was visible in the online conversations. For example, Elaine began to perceive herself as an advocate for marginalized students in her school and to take actions to promote change. Rita began to see her professional setting as constraining, and started planning a move to an alternative education setting which she perceived as offering more scope for improved pedagogy. Judy articulated her deeply held beliefs about the importance of having respect for students' cultural views and began to plan a career with individuals from diverse languages and cultures. Patrick initiated the development of online course delivery in his college, and began to design his own online course.

The examination of discursive devices in the course transcripts revealed means by which processes of conceptual development and social negotiation occur in online interaction. The results have implications for understanding how topical and social cohesion are established in online discussion, and show how participants use patterns of agreement and disagreement rhetorically to convince others and to learn from others' perspectives, while also protecting the trust and inclusiveness of the online community.

These findings have implications for designers and instructors of online courses. Although not a typical online course by its nature, in that it was at the graduate level, had a small number of participants, had the active involvement of the instructor, and its focus was classroom discourse, it was highly successful. These results favor a constructivist approach of designing online courses around discussion processes rather than the transmission of information. Encouraging participants to bring their practical experiences into theoretical discussions appeared to facilitate deep theory-practice connections, as well as high levels of engagement. It also seems important to design online courses to allow students to pursue their own interests, follow different paths of thinking, and produce different products, rather than insisting on the same from everyone. It is important for the instructor to require respectful interaction and to model it, as well as to model community building devices, coherence strategies, negotiation, and higher level thinking. Finally, participation in discussion must be a course requirement. These findings echo Kanuka's (2005) design principles, which include the provision of opportunities to engage with abstractions, consider multiple perspectives, and challenge one's own world view; implementation of course activities that are relevant to the learners and open to diverse ways of knowing; and the requirement for learners to build meaning and take responsibility for their learning (p. 4).

Future research can assess whether these instructional and design characteristics are as successful in other online contexts. Research is needed to determine whether similar discourse devices are used effectively for community building and discursive coherence in online courses with larger numbers of participants, over longer time frames, or when participants have different or more heterogeneous backgrounds (Colomb & Simutis, 1996; Kim & Bonk, 2002; Wolfe, 2000). Interrelationships between online discourse and aspects such as gender, social climate, instructor presence, and instructional design elements of the learning environment also warrant investigation.

Barab, S. A., MaKinster, J. G., Moore, J. A., & Cunningham, D. J. (2002). Designing and building an on-line community: The struggle to support sociability in the inquiry learning forum [Electronic version]. Educational Technology Research and Development, 49(4), 71-96

Blanton, W. E., Moorman, G., & Trathen, W. (1998). Telecommunications and teacher education: A social constructivist review. Review of Research in Education, 23, 235-275.

Boyd, J. (2002, April). In community we trust: Online security communication at eBay. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 7(3). Retrieved June 2, 2003, from http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol7/issue3/boyd.html#Model

Brown, R. E. (2001, September). The process of community-building in distance learning classes. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 5(2), 18-35. Retrieved June 3, 2003, from http://www.aln.org/publications/jaln/v5n2/pdf/v5n2_brown.pdf

Colomb, G. G., & Simutis, J. A. (1996). Visible conversation and academic inquiry: CMC in a culturally diverse classroom. In S. C. Herring (Ed.), Computer-mediated communication: Linguistic, social and cross-cultural perspectives (pp. 201-222). Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

Conrad, D. (2005). Building and maintaining community in cohort-based online learning [Electronic version]. Journal of Distance Education, 20(1), 1-20.

Cooper, M. M., & Selfe, C. L. (1990). Computer conferences and learning: Authority, resistance, and internally persuasive discourse. College English, 52, 847-869.

Davis, B. H., & Brewer, J. P. (1997). Electronic discourse: Linguistic individuals in virtual space. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Denzin, N. K. (1995). The experiential text and the limits of visual understanding. Educational Theory, 45, 7-18.

Doolittle, P. E. (1999, November). Constructivism and online education. Paper presented at the 1999 Teaching Online in Higher Education virtual conference. Retrieved November 9, 2000, from: http://as1.ipfw.edu/1999tohe

Doolittle, P. E. (2000, November). Online pedagogy: The ill-structured nature of web-based instruction. Paper presented at the 2000 Teaching Online in Higher Education virtual conference. Retrieved November 9, 2000 from: http://as1.ipfw.edu/2000tohe/papers/doolittle.htm

Enomoto, E., & Tabata, L. (2000, November). Creating virtual communities through distance education technologies. Paper presented at the 2000 Teaching Online in Higher Education virtual conference. Retrieved November 9, 2000, from: http://as1.ipfw.edu/2000tohe/master.htm

Ferrara , K., Brunner, H., & Whittemore, G. (1991). Interactive written discourse as an emergent register. Written Communication, 8(1), 8-34.

Frank, T. (2000, October). Universities compete for a presence online. University Affairs (pp. 10-14). Ottawa, ON: Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada.

Fraser, D. (1999, September). QSR NUD*IST VIVO: Reference guide (2nd ed.). Melbourne, Australia: Qualitative Solutions and Research.

Gabriel, M. A. (2004). Learning together: Exploring group interaction online [Electronic version]. Journal of Distance Education, 19(1), 54-72.

Gee, J. P., & Green, J. L. (1998). Discourse analysis, learning, and social practice: A methodological study. Review of Research in Education, 23, 119-169.

Granville, S. (2003). Contests over meaning in a South African classroom: Introducing Critical Language Awareness in a climate of social change and cultural diversity. Language and Education, 17(1), 1-20.

Harasim, L. M. (1990). Online education: An environment for collaboration and intellectual amplification. In L. M. Harasim (Ed.), Online education: Perspectives on a new environment (pp. 39-64). New York: Praeger.

Haughey, M. & Umbriaco, M. (2005). Editorial [Electronic version]. Journal of Distance Education, 20(1), 1-3.

Haughey, M., Umbriaco, M., Lavoie, L., & Pettigrew, F. (2005). Editorial [Electronic version]. Journal of Distance Education, 20(2), 1-3.

Haythornthwaite, C. (2005). Introduction: Computer-mediated collaborative practice. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 10(4). Article 11. Retrieved January 11, 2006 from: http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol10/issue4/haythornthwaite.html.

Haythornthwaite, C., Kazmer, M., Robins, J., & Shoemaker, S. (2000). Community development among distance learners: Temporal and technological dimensions. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 6(1). Retrieved February 14, 2001, from: http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol6/issue1/haythornthwaite.html.

Herring, S. (1999). Interactional coherence in CMC. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 4(4). Retrieved March 1, 2001, from: http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol4/issue4/herring.html

Honeycutt, L. (2001). Comparing e-mail and synchronous conferencing in online peer response [Electronic version]. Written Communication, 18(1), 26-60.

Jewitt, C., & Kress, G. (Eds.) (2003). Multimodal literacy. New York: Peter Lang.

Jonassen, D., Davidson, M., Collins, M., Campbell, J., & Haag, B. B. (1995). Constructivism and computer-mediated communication in distance education. The American Journal of Distance Education, 9(2), 7-26.

Kanuka, H. (2005). An exploration into facilitating higher levels of learning in a text-based internet learning environment using diverse instructional strategies. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 10(3), article 8. Retrieved January 11, 2006 from: http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol10/issue3/kanuka.html.

Kanuka, H., & Anderson, T. (1998). Online social interaction, discord, and knowledge construction. Journal of Distance Education, 13(1), 57-74.

Kim, K., & Bonk, C. J. (2002). Cross-cultural comparisons of online collaboration. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 8(1). Retrieved June 2, 2003, from: http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol8/issue1/kimandbonk.html

Korenman, J., & Wyatt, N. (1996). Group dynamics in an e-mail forum. In S. C. Herring (Ed.), Computer-mediated communication: Linguistic, social and cross-cultural perspectives (pp. 225-242). Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

Kvale, S. (1996). InterViews: An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lapadat, J. C. (2000a). Teaching online: Breaking new ground in collaborative thinking. Syracuse, NY: ERIC Clearinghouse on Information & Technology. (ERIC Document Reproduction No. ED 443 420).

Lapadat, J. C. (2000b, November). Tracking conceptual change: An indicator of learning online. Paper presented at the 2000 Teaching Online in Higher Education virtual conference. Retrieved November 9, 2000, from: http://as1.ipfw.edu/2000tohe/papers/lapadat.htm

Lapadat, J. C. (2000c). Problematizing transcription: Purpose, paradigm, and quality. International Journal of Social Research and Methodology: Theory & Practice, 3, 203-219.

Lapadat, J. C. (2002). Written interaction: A key component in online learning. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 7(4). Retrieved August 19, 2002, from: http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol7/issue4/lapadat.html

Lapadat, J. C. (2003). Teachers in an online seminar talking about talk: Classroom discourse and school change. Language and Education, 17(1), 21-41.

Lapadat, J. C. (2004). Online teaching: Creating text-based environments for collaborative thinking. The Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 50, 236-251.

Lapadat, J. C., & Lindsay, A. C. (1999). Transcription in research and practice: From standardization of technique to interpretive positionings. Qualitative Inquiry, 5, 64-86.

Li, H. Z. (1999). Grounding and information communication in intercultural and intracultural dyadic discourse. Discourse Processes, 28, 195-215.

McComb. M. (1994). Benefits of computer-mediated communication in college courses. Communication Education, 43, 159-170.

McDonald, J. (2002, August). Is “as good as face-to-face” as good as it gets? Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 6(2), 10-23. Retrieved June 3, 2003, from: http://www.aln.org/publications/jaln/v6n2/pdf/v6n2_macdonald.pdf

Mishler, E. G. (1991). Representing discourse: The rhetoric of transcription. Journal of Narrative and Life History, 1, 255-280.

Molinari, D. L. (2004). The role of social comments in problem-solving groups in an online class [Electronic version]. The American Journal of Distance Education, 18(2), 89-101.

Murphy, K. L., & Collins, M. P. (1997). Development of communication conventions in instructional electronic chats. Journal of Distance Education, XII(1/2), 177-200.

Preece, J., & Maloney-Krichmar, D. (2005). Online communities: Design, theory, and practice. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 10(4), article 1. Retrieved January 11, 2006 from: http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol10/issue4/preece.html.

Richards, L. (1999, September). Using NVivo in qualitative research (2nd ed.). Melbourne, Australia: Qualitative Solutions and Research.

Roschelle, J., & Pea, R. (1999). Trajectories from today's WWW to a powerful educational infrastructure. Educational Researcher, 28(5), 22-25, 43.

Rose, M. A. (2004). Comparing productive online dialogue in two group styles: Cooperative and collaborative [Electronic version]. The American Journal of Distance Education, 18(2), 73-88.

Rourke, L., Anderson, T. Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (1999). Assessing social presence in asynchronous text-based computer conferencing. Journal of Distance Education, 14(2), 50-71.

Rovai, A. P. (2001). Building classroom community at a distance: A case study [Electronic version]. Educational Technology Research and Development, 49(4), 33-48.

Rovai, A. A. P. (2002). A preliminary look at the structural differences of higher education classroom communities in traditional and ALN courses. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 6(1), 41-56. Retrieved June 3, 2003, from: http://www.aln.org/publications/jaln/j6n1/pdf/v6n1_rovai.pdf

Schallert, D. L., Dodson, M. M., Benton, R. E., Reed, J. H., Amador, N. A., Lissi, M. R., Coward, F. L., & Fleeman, B. F. (1999, April). Conversations that lead to learning in a computer age: Tracking how individuals make sense of socially shared classroom conversations. Paper presented at the meeting of American Educational Research Association, Montreal, QC.

Schallert, D. L., Lissi, M. R., Reed, J. H., Dodson, M. M., Benton, R. E., & Hopkins, L. F. (1996). How coherence is socially constructed in oral and written classroom discussions of reading assignments. In D. J. Leu, C. K. Kinzer, & K. A. Hinchman (Eds.), Literacies for the 21st century: Research and practice (pp. 471-483). Chicago, IL: The National Reading Conference.

Stacey, E. (1999). Collaborative learning in an online environment. Journal of Distance Education, 14(2), 14-33.

Stewart, F. & Eckerman, E. (1999, February). Gender and the net: Methodological issues in virtual research practices. Paper presented at the Advances in Qualitative Methods conference, Edmonton, AB.

Weasenforth, D., Biesenbach-Lucas, S., & Meloni, C. (2002, September). Realizing constructivist objectives through collaborative technologies: Threaded discussions. Language Learning & Technology, 6(3), 58-86. Retrieved June 3, 2003, from: http://llt.msu.edu/vol6num3/weasenforth/

Whittle, J., Morgan, M., & Maltby, J. (2000). Higher learning online: Using constructivist principles to design effective asynchronous discussion. Paper presented at the NAWEB 2000 virtual conference. Retrieved April 8, 2002, from: http://naweb.unb.ca/2k/papers/whittle.htm

Wolfe, J. (2000). Gender, ethnicity, and classroom discourse [Electronic version]. Written Communication, 17(4), 491-519

Judith C. Lapadat, Northwest Regional Chair for the University of Northern British Columbia and Professor of Education, publishes in both scholarly and literary realms. Her academic work, focused on language, literacy, technology, distance education, and qualitative research methodologies, has been published internationally. She has recent publications in the Journal of Educational Psychology, Qualitative Inquiry, the International Journal of Social Research Methodology, Language and Education, and the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. Her current research focus on multimodal literacies in electronic environments is funded by a three year grant awarded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Right Answer Thread

010 Rita

[Rita introduces the idea of the “right answer” using other terminology]

The notion of the teacher having the answer in mind (preset) is something I've really been thinking about since the Hicks article. I know it's true, but it's really true. I don't know how many times I've had an answer in mind when I asked a question. I've had a hard time accepting the student's answer because it wasn't what I expected.

022 Professor

[affirms Rita's remark and contrasts teachers who pose test questions with those who promote discussion]

teachers (at all levels: k-12 through to university) have a long history of being the holders of the knowledge, and drilling students with test questions (ones to which the teacher already knows the answer). This results in a different kind of discourse than in classrooms organized around discussion and shared experience

031 Rita

[affirms Professor's remarks, coins the term “right answer,” and adds that a focus on rights answers leads to a fear of errors and risk-taking in transmission-oriented classrooms that is counter-productive]

So often, as has been discussed before, we (teachers) have the "right" answer. Doesn't really allow for any construction of meaning or expansion does it? I read through all the prototypes, but carefully read #7, Fifth Grade, Exploring Our Roots. The notion of teachers enriching, creating more interest and more exploration is overwhelming. Error has a totally different meaning in this situation. Students are encouraged to take risks and hypothesize and therefore expand their knowledge. In the transmissional classroom, facts are learned but I don't believe there is risk taking to this extent. We talk about trying to create critical thinkers, problem solvers, innovative citizens ... need I say more?

047 Lisa

[Says her task as an adult educator is to foster problem solving and risk taking, rather than emphasizing the right answer]

As an adult educator, I have found that a majority of my students feel that their thoughts and opinions have no value. My major job with a new group of students is to create a 'safe' atmosphere where prior knowledge, life experience, values and opinions are seen as valuable

054 Rita

[Comments that despite what individual teachers do, exams and standardized tests emphasize the right answer]

Hi Lisa, I can't agree with you more. This right answer business is really concerning me. Even though we say we're after critical thinkers and problem solvers and trying to make our students (no matter the age) lovers of learning, the "right answer" still sits out there. Even if not in our class at a particular moment, but out there on government or standardized exams.

164 Lisa

[Says that teachers do not have to present themselves as knowing all the answers]

As for the view that students often have that teachers know all the answers, or at least the one 'right' answer, I tell my students that being a teacher doesn't mean that you have to know all the answers, but you do have to know where to look for them!

167 Rita

[Disagrees, saying that students do expect teachers to know the answers]

Hi Lisa, students sure don't like to hear that you as teacher don't know everything. After all they think we have all the knowledge at our finger tips. I think once they can accept that we are humans, too, there is a difference in their approach to us.

168 Lisa

[Proposes the idea of multiple truths]

We are still looking for the 'right' answer for all of our questions, when in actual fact, as we have learned there can be many, many answers depending on how you approach the question.

181 Rita

[Remarks that curiosity is killed off in science by the quest for the right answer, thus negating learning]

I think that the process of learning science shouldn't kill off the curiousity and I believe that is what happens. Children come with great curiousity, but when you have to come up with the "right" answer (back to that), why take a risk? … I guess what really comes across to me is this whole notion of school being a place for exploration rather than looking for the right answer. We give lip service to allowing children to make guesses, but it is towards the right answer not to further exploration. There are valid reasons why we need to move on, be efficient, get good marks, prepare for exams, but is that learning?

183 Lisa

[Reintroduces the issue of accountability, discussed earlier in the course, but not previously linked to the term “right answer”]

Hi Rita, I should be on my way out the door, but I just read your response to the readings this week and I had to comment! I'm so glad that right answers in math will solve all the problems! It gets so frustrating! There is all this talk about accountability, but who is accountable for passing on the 'joy' of learning and the 'hunger' to keep learning for the rest of your life? How do you measure that?

197 Professor

[Challenges the class to address the argument that focusing on right answers is a more efficient way to teach, and to consider the political implications of pedagogical approach]

So, Rita, are you suggesting that school has become this place where students memorize and replicate/demonstrate others' "right answers" for rewards? Why, as a society would we want school to be that way? Why as teachers do we let it be that way? Haven't people argued that students need to know so much that its more efficient to have them cram it all in by memorizing it (covering the curriculum)—discovering and exploring just takes too long?

202 Judy

[Links the focus on right answers to an emphasis on marks, as contrasted with learning]

“… There are valid reasons why we need to move on, be efficient, get good marks, prepare for exams, but is that learning?" No, it is not learning! I think that the first time that I really learned anything was in this program. Like I said before, students learn that when they are in high school they need top marks to get into university, once in university students learn that you need top marks t o get into graduate school …. the list goes on!

207 Rita

[Responds to Professor's challenge by pointing out that control of knowledge is political and in the hands of those who hold power]

Professor I don't have a clue why we would want an education system where 'right answers'(prespecified goals) are the goal instead of education system based on intellectual inquiry or creative activity. There are many different views on what is valuable, what knowledge should be embodied in the curriculum, and how is success is measured. Academic boundaries are culturally produced and result in the adoption of an ideology of thoes who have the power to enforce it (thanks Dr. A.L.). I believe teachers are in danger of become 'workers' instead of educators.

208 Elaine

[Links the focus on right answers to political and administrative expediency — under-funding of education leaves teachers few choices in how to teach]

Classroom teachers are not miracle workers. We need resourses, more importantly the kids do. Teachers did try to prevent this from happening. We presented our objections and concerns, backed up by reasearch, to the board, and faxed members of parliament both federally and provincially. We were told there was no money. The effort to save the Almighty dollar should not be placed on the backs of our most needy children. Educational opportunities of children should not be limited in order to subsidize the governments insufficient funding to education. It may seem that I have wandered off the topic but I believe the present emphasis on 'right answers' which can be measured? is part of a much bigger picture.

219 Elaine

[Argues for dialogue, compromise and diverse perspectives]

Dialogue is essential to learning — the capacity to communicate, share decisions and arrive at comprimises. The IRA pattern of classrooms is alive and well in schools. We tend to put a lot of emphasis on mathmatical reasoning but very little on interpersonal reasoning. It is through dialogue that other points of view are presented. Part of what we need to learn is that we do not need to reject ideas 'wholly'- not all right or all wrong. Definition of polysemy: diversity of meaning

244 Professor

[Agrees with Elaine's point about allocation of resources]

332 Rita

[Summarizes the right answer thread]

Parts of the article we have discussed before, the emphasis on the right answer and knowledge in the full control of the teacher. I guess a question that came to me is, how do you measure a classroom of thinkers? It's so much easier to measure facts on an exam - in fact, why do we have exams? What exactly is the purpose? It kind of goes against everything we've been looking at in a way. Cook's little list of how people learn best (engaged, explore, reflect, and assess what and how they have learned) doesn't really match up with multiple choice answers - does it? I find that I often - to save time - give out what I feel the students need to know. That doesn't allow for prior knowledge or any ownership, but I honestly don't know how else to get through the curriculum that they and I need to. When the students do their "own thing" the results are rewarding for all of us. Not only that, what they do on their own, stays with them so much longer. Unfortunately, once again, that may not be the focus of the exam. With years of exams in my files, I can sort of predict what will be asked on the government exam - the students may not necessarily be interested in that same focus (although they want to do well on the exams because of scholarships). So, how do I work that together so we're all happy? Further, I believe there has to be some transmission of knowledge so that the students will have the background to ask the questions to take them on a journey. Otherwise they stay with what they know. We are after all interested in expanding their minds aren't we? … Dewey's comment on page 136 "school knowledge built through presentational function, then, will tend to oversimplify issues, smooth over potential controversy, avoid obstacles and exclude anything novel from being explored or discovered." Yikes, that is scary - that was in 1933, and it's still true in 1998. A funny line was the "spoonies" - is that what we're raising here? As always, a final quote from the end of the article, that kind of sums up what is important here, "when learners are given a voice in their own learning and opportunities to build knowledge collaboratively, their already present potential for engagement in learning will be tapped. This is the real purpose for encouraging classroom talk."

350 Rita

[Rita describes the focus of her classroom research project]

I'm looking at how I (as teacher) use oral language in my classroom and the extent to which I give my students ownership and an opportunity to move beyond factual information and going for the "right answer".

Appendix B

First Series of Disagreements with Patrick (Summarized)

067 Judy