Beyond Andragogy: Some Explorations for Distance Learning Design |

Andragogy has gained wide publicity in the past 20 years in North America as a concept and as a set of principles for helping the learning processes of adults. The author argues that a closer examination of the concept should contribute to learning design development and research in distance education and to the convergence of classroom educators and distance educators. The original meanings of the concept are explored and related to the concept of learner-centredness. A model of learner-centredness is explained and a selected set of relevant issues and design/facilitation guidelines presented.

L’andragogie en tant que concept et ensemble de principes favorisant le processus d’apprentissage des adultes recoit l’attention des milieux d’éducation en Amérique du Nord depuis au moins vingt ans. L’auteur de cette étude soutient qu’une analyse approfondie du concept d’andragogie devrait permettre d’améliorer les modèles pedagogiques et la recherche en formation è distance. De plus il croit que cette étude pourrait contribuer au rapprochement entre les praticiens des institutions traditionnelles et les praticiens des institutions de formation à distance. L’auteur examine ensuite les définitions de ce concept d’andragogie et tente d’établir un lien entre ces dernières et le concept de l’apprentissage centré sur l’apprenant. Il décrit un modèle d’apprentissage centre sur l’apprenant, soulève les questions pertinentes è ce concept et propose des consignes pour faciliter la crèation de modèles semblables.

It was 20 years ago this year that the term andragogy began to be used in North America. As Malcolm Knowles tells the story, he was introduced to the term by a Yugoslav adult educator, Dusan Savicevic in the summer of 1967, and began using it consistently in 1968. It was no coincidence about Savicevic’s nationality: Yugoslavia. Poland. FRG. GDR. the Netherlands and Czechoslovakia have been the few European countries to consistently use the term andragogy to refer to both the practical aspects of helping adults to learn and to the academic study of adult education and learning. Knowles formally introduced andragogy to North America in his book The Modern Practice of Adult Education (1970).

Since 1970, the term has gained both approval and approbation. Adult educators have adopted and modified Knowles’s principles and conditions, writers have extended the concept of andragogy into a broader term of learner centredness, and debate has raged over the conceptual and practical usefulness of Knowle’s use of the term andragogy in face-to-face adult education. There are many reasons for examining this controversial concept and its conceptually related term, learner-centredness, from a distance education perspective. This paper outlines those reasons; explains the original concept, discussions of it by colleagues, and its development into learner-centredness; and offers some guidelines for the reader’s assessment.

Andragogy has several uses to distance educators. The general learning processes and life conditions of adult distance learners are similar to those of adult classroom learners. The observations and experiences of such classroom based writers as Malcolm Knowles should not be discounted as irrelevant on the grounds that distance learning contexts create different types of learners or that distance leamers are denied any form of classroom type activity. The widening use of two-way communications technologies is, in fact, helping distance educators develop their own kinds of interactive classrooms: small and large, local and regional group configurations of learners are created via telephone classes, computer conferencing and face-to-face meetings and workshops. Given this trend, we may also be able to develop closer links with classroom educators and break down the professional ‘‘breed apart’‘ connotation of distance educators (Smith and Kelly, 1987).

The second reason for distance educators to look at andragogy is the concept of quality. Five years from now, which criteria will we use to measure improvements in distance learning? Greater learner autonomy and choice? Greater educator control and predictability? Faster interactions? Will the criteria enable integrative, holistic assessments, or narrow views on fragmented aspects of the learning experience? How might we usefully expand existing sets of criteria (Burge, 1984; Kaye and Rumble, 1981; Holmberg, 1986a)? Would an andragogical learner-centred approach contribute to or undermine academic rigour? I believe that a closer examination of the key implications of andragogy and a learner- centred view within the new classrooms of distance education will contribute to academic rigour. It will also expand the definitions of helping adults learn to include more of the subtle qualitative aspects of learning.

The quality of counselling and tutoring, as distinct from quality of course content, is another professional issue that benefits from a closer look at andragogy. Classroom higher educators have written at length about the regrettable but inevitable lack of academic emphasis on the process of teaching, and of helping people to learn (e.g. Ryan, 1987). Distance educators have stressed the design of materials that are learner- sensitive (Jenkins, 1981; Henri and Kaye, 1985; Cranley, 1986), and the use of sensitive and skilled techniques by counsellors and tutors (e.g., Coltman, 1983; Woolfe, Murgatroyd and Rhys, 1987). Would a sharper focus on the adult learner promote further development or be perceived as a threat to the present roles and functions of the course designer, writer, counsellor, and tutor? Would counsellors have different kinds of tasks if tutors and course designers took more notice of andragogical and learner- centred principles? Or, to revise the question: to what extent is the work of counsellors and tutors needed to compensate for some inappropriate course designs?

Another aspect of quality relates to assumptions and methodologies of research in distance education. If the production of knowledge about distance learners, learning processes and tutoring strategies is to develop beyond experimental methods, it will do so through the greater use of methods that focus on how learners perceive and interpret their realities (Jacobs, 1987; Taylor and Bogdan, 1984), a very different approach from that of the positivist, experimental design. Distance educators have begun to use “whole-learner” approaches (e.g., Kelly and Shapcott, 1987): could closer looks at the assumptions and values of andragogy encourage the use of naturalistic research orientations? And to be even more lateral in thinking, could an andragogical focus help promote non sexist research, that is, would such a focus acknowledge the separate and legitimate constructions of women’s knowledge of the world (Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger and Tarule, 1986) and avoid the sexist problems recently listed by Margrit Eichler (Eichler, 1988)? I believe that the answers to both questions are yes, given andragogy’s basic emphasis on respect for what the learners have done so far in their lives.

Third, there has been little significant discussion over the last ten years about the extent to which learning designs used in distance education are truly adult learner-centred and based in adult learning literature. Neither has there been discussion of the implications of taking such a view in relation either to the needs of the educational “establishment,” or to the use of instructional design/training (Coldeway, 1987) or information processing models of teaching (Ausubel,1968). Farnes has questioned the limits of Open University (UK) designs (Farnes, 1975), and several designers have written about their own use of andragogical principles in distance contexts (Jarvis, 1981; Fales and Burge, 1984; Taylor and Kaye, 1986). Some distance educators have looked at more effective and inter relational aspects of learnin~ desi~ns: HolmberR’s guided didactic conversation’‘ (Holmberg, 1986b); Hough’s ideas on motivation (Hough, 1984), Moore’s and Willen’s concern with self direction and independence (Willen, 1984; Moore, 1986); Inglis’ research on effective development (Inglis, 1987); and Atman’s with conation (Atman, 1987). These and other discussions are not integrated enough within a single perspective to balance the current strength of the instructional technology and systems approaches to course design (e.g., Briggs, 1977; Posner and Rudnitsky, 1986). I believe that distance educators need a sophisticated learner-centred v3ew of learning and teaching that shows a critical integration of knowledge from various disciplines and fields of practice, including adult education. The concept of andragogy, which leads to the broader understanding of an adult learner- centred orientation, needs to be part of that critical process.

Knowles drew on a variety of disciplines to develop his concept of andragogy (Knowles, 1978, 1980, 1985). From early adult learning ideas (Lindeman, 1926) psychotherapy, humanistic psychology (e.g., Maslow, 1968; Rogers, 1969), developmental psychology (Erickson, 1950) and other social science disciplines, he developed the assumptions and techniques which he considered most appropriate for the facilitation of adult learning. He explained the origins of the term: “aner” from the Greek meaning man as distinguished from boy (i.e., in today’s non-sexist terms, an adult) and “agogus” meaning leader of (Knowles, 1978, pp. 53-54). The term was originally intended as a contrast to pedagogy, and to avoid the use of such contradictory phrases as the pedagogy of adult learning. His andragogical model focused on process—”the art and science of helping adults learn”—with conscious recognition of the adulthood of adult learners. Adulthood in Knowles’s terms was characterized by problem centered, immediate application of learning, a readiness to learn based in the developmental tasks of maturation, an expanding repertoire of experience, and a self-concept determined by self direction.

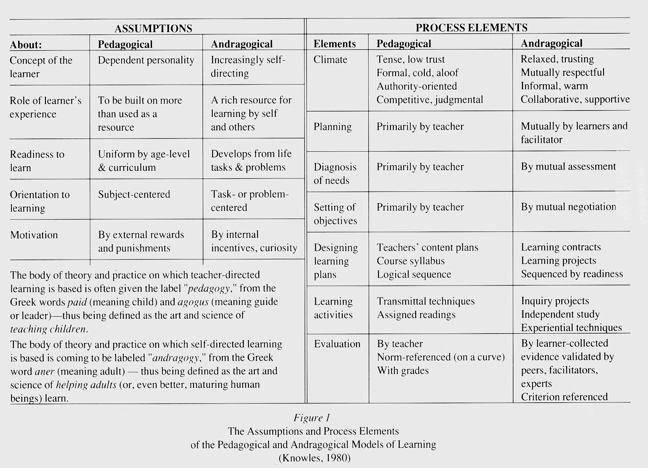

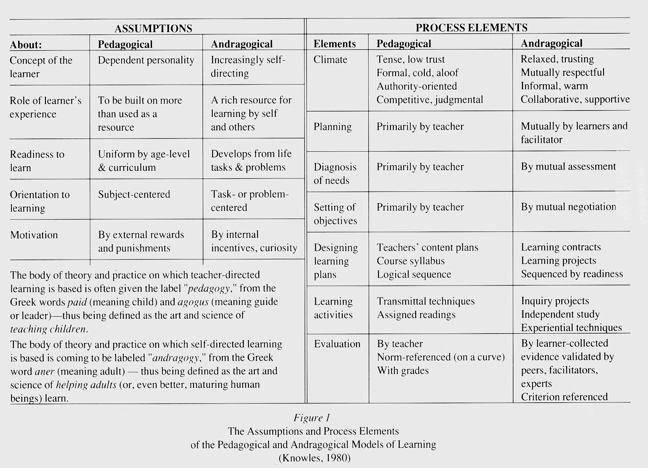

Roger’s concept of “student-centered teaching” (Rogers, 1969) influenced Knowles’s phases for the development of learning activities: the phases dealt first with establishing a conducive climate and structures for participation in planning before needs were diagnosed, objectives set, and activities designed (Knowles, 1980). He contrasted this process to the pedagogical model and its focus on content—what is learned. The best known comparison of the models is shown in Figure 1. But after feeling the heat of continuing controversy and debate (outlined in the following section), he clarified his definition of andragogy to mean “a system of concepts that, in fact, incorporates pedagogy rather than opposing it” (Knowles,1985, p.8).

In Cross’s words, the whole issue of andragogy has

heightened the awareness of the need for answers to three major questions: (I) Is it useful to distinguish the learning needs of adults from those of children?...(2) What are we really seeking: Theories of learning? Theories of teaching? Both? (3) Does andragogy lead to researchable questions that will advance knowledge in adult education (Cross,1981, pp. 227-228)?

Knowles has been most especially criticized for his comparisons between learning processes in children and in adults, for his use of self- directedness as a definition of adulthood, and for the lack of explanatory or predictive power of his ideas. Hartree for example identified three major problems:

a confusion between whether he is presenting a theory of teaching or one of learning; a similar confusion over the relationship which he sees between adult and child learning; and a considerable degree of ambiguity as to whether he is dealing with theory or practice (Hartree, 1984, p.204).

She argued that his development of the term andragogy “lacks coherent discussion of the different dimensions of learning’‘ and “does not incorporate an epistemology” (Hartree, 1984, p. 209). Tennant took Knowles to task for his reliance on the goal of self actualization as a motivator for adult development, on the ethic of individualism, and the presumed effectiveness of learning contracts; and for his support of three “myths” of adult learning—”the myth that our need for self-direction is rooted in our constitutional make-up; the myth that self-development is a process of change towards higher levels of existence; and the myth that adult learning is fundamentally (and necessarily) different from child learning” (Tennant, 1986, p. 121). The Nottingham Andragogy Group (NAG) issued their own definition, assumptions, salient features and stages for establishing an andragogic process that is justified because adults are existentially different from children (N.A.G. 1983). Yonge’s contribution to the andragogy- pedagogy debate focussed on the nature of the relationship between teacher and l learner. He argued that for the teacher

there are important differences in guiding a child and in guiding another adult. If these differences are not respected, this can , undermine the relationships of mutual trust and understanding with the consequence that the relationship of authority will change from an authoritative to an authoritarian one (Yonge, 1985, p. 166).

An andragogic situation involves one adult using authority in particular ways (that are different in a pedagogic situation) to help another adult toward “a more refined, enriched adulthood.”

In addressing the criticisms of his earlier contrasts between pedagogy and andragogy, Knowles argued that educators now have a choice of model, i.e.,pedagogy or andragogy, and that they need to be able to recognize the conditions for which each model may be appropriate. He admitted that the age-related distinction between the models was not useful—”there is growing evidence that the andragogical assumptions are realistic in many more situations than traditional schooling has recognized’ ’ (Knowles,1985,p.13).

Davenport, in trying to clarify a confusing situation, and writing after this statement of Knowles (Davenport, 1987), used the age factor in a different way.

He revised the definition of andragogue to “adult leader,” claiming it to be a more literal one that reduces the “conceptual confusions” because it includes all the generic issues associated with adult learners: developmental stages, self direction in learning, physiological and psychological conditions, emotions, etc. Pedagogy, on the other hand, would refer to all the same generic issues but as they are associated with pre-adult learners. Teaching and learning processes are not then the things that necessarily divide andragogy and pedagogy—what does divide are the contextual, societal and developmental factors relating to the people concerned. Davenport and Davenport summarized the andragogy debate to 1984 in a useful analysis to which readers are referred (Davenport and Davenport,1985).

The latest published critique of Knowles’s assumptions has come from Dan Pratt. Pratt used a relational perspective in his critique of Knowles’s assumptions about the self directed nature of adulthood and its direct association with learner control (Pratt, 1988). He argues that not all adults show “desire capability and readiness to exert control over [instructional] functions” and that no assumptions should be made that collaborative learning methods are either automatically linked into self direction or are always appropriate. He integrates common sense, and practical knowledge to argue that the presence of situational, learner and teacher variables will determine how much self direction and collaboration is possible or appropriate. He deals with the andragogy- pedagogy distinction by arguing that it is best based on variations in learner dependency in specific situations, and in the consequent differences in the relationship between learner and teacher.

Dorothy MacKeracher has summed up her opinion of the andragogy discussions as three points. First, the term produced an interesting academic debate. Second, adults will learn in spite of what educators do to them, but children may be affected more strongly by the negative experiences imposed by educators. Third, the educator must always attend to adult learner’s concerns and ways of understanding her/his world -- all must be accepted because each has helped the adult get through life. the real challenge for the educator then is to find out how she/he may expand the world of the learner (MacKeracher, 1988).

Research projects concerning andragogy, as Knowles defined it, have included testing the andragogical-pedagogical orientations of educators (e.g., Holmes, 1980) and of learners (e.g., Davenport, 1984), analyzing from andragogical perspectives the experiences of Canadian university and college students (Lam, 1985), and graduate students (Briggs, 1982; Roy-Poirier, 1986); and developing an instrument to measure the social environment of adult learning classrooms (Darkenwald and Valentine,1986). Lam’s results, for example, indicated that his research subjects wanted to see andragogical principles applied:

The majority of adult learners express a desire for more but not complete partnership in the planning, organizing, delivering and evaluating of courses. The basic premise of the learner- centred approach proposed by the principles of andragogy rests a great deal on the cognitive maturity of adult learners. Adult learners who lack formal education, and are operating in what Perry termed ‘‘dualistic mode” (Perry, 1970), prefer a more structured learning environment than do more sophisticated learners who operate in a “relativistic position” (Lam,1985, p.51).

Roy-Poirier’s and Brigg’s research also indicated adult learner preferences for andragogical approaches to learning and its facilitation (Briggs, 1982; Roy Poirier, 1986).

Where is an adult educator left at the end of all these discussions in terms of dealing with Knowles’s assumptions? In my view, the key points may bell’ grouped under two headings: the effects of individual differences, and the context of learning. Adult students in a course will show subtle and not so subtle differences in learning and cognitive styles and variations in psychosocial, intellectual, moral and other development continua. Some individuals will be very dependent, some independent and others interdependent in terms of how they relate to a teacher or tutor in specific situations. No assumption therefore should be made that self-direction is an evident need or style of adulthood. Life experiences may be a resource for learning, but they may also act as hindrances, especially where adults are not confident about themselves as learners. Some will be looking for expedient short cuts because of time pressures and will n want to invest time in the collaborative planning and climate setting processes that Knowles values. Others will be learning not in order to solve an immediate problem but for the joy they experience in new discoveries. In short, differences in maturational stages, and in life roles will create more differences in learning needs and styles than Knowles accounted for in his original assumptions.

Teachers and tutors of those adults also will show wide variations in maturational stages and needs for power and control. Many educators for example are conditioned to work in transmittal authoritative modes; others know no other styles for working with learners, or are psychologically unprepared to give up leadership and control.

Two points may be made concerning contexts of learning and the activity of the teacher or tutor. First, what is important, in this writer’s opinion, is not slavishly to follow Knowles’s prescriptions and assumptions, but to find an accommodation between the laid-on demands of a course - the content/discipline requirements, the professional judgements of the responsible teacher/s, and the institutional regulations - and the more subtle conditions and demands of the students, based on their teacher relationship needs and what they currently understand about the world. The educator has to make deliberate choices about which model/s of teaching may be appropriate for given situations within a course (Joyce and Weil, 1986), but this should be done within an overriding concern to show openly respect, sensitivity and warmth for the learner as an adult person. There is another aspect to showing a keen regard for individuality: the educator has to decide whether she/he wants to encourage student growth beyond the course by the acquisition and use of learning-how-to-learn skills to get ‘‘the fishing rods” as well as the “fish.” Dealing with individuality, showing respect and openness, and helping the learner acquire some skills for personal change and growth beyond the immediate bounds of the course are not easy when added to the content demands of a course.

The second point to make as part of the context of learning is to acknowledge the impact of Knowles’s ideas on practitioners and writers in adult education. It is fair to say that the discussions of andragogy as he outlined it have been referenced in many articles, and have helped to develop what I believe is a more useful term - the “learner-centred view.”

Several writers have discussed what it means for an adult educator to take a learner-centred view and recognize the adulthood of adult learners (e.g., Knox, 1986; Cross, 1981; Mezirow, 1981; Brookfield, 1986; Boud and Griffin, 1987; Brundage and MacKeracher, 1980; Brandes and Ginnis, 1986). Guidelines for what is now termed the facilitation of adult learning are widely used to show a learner-centred focus in operation. They include many of Knowles’s original techniques, especially those demanding open and collaborative work with learners (as far as possible) and activity that recognizes the life experiences of the learner.

All these guidelines are both challenging and rewarding - especially challenging for teachers who have operated within highly directive, transmitter of-knowledge modes. How does this affect a distance adult educator caught between a personal philosophic acceptance of a learner- centred view and the prevalence of highly directive, transmittal models of distance education b teaching?

Having argued earlier that it is appropriate for distance educators to examine andragogy and the wider term of a centered view, it is time to outline some guidelines under which such a view could be implemented.

Those guidelines have emerged from a personal model of a learner- centred view and from a number of substantive questions that refuse to fade away. No apologies are made for the apparent simplistic nature of the following points.

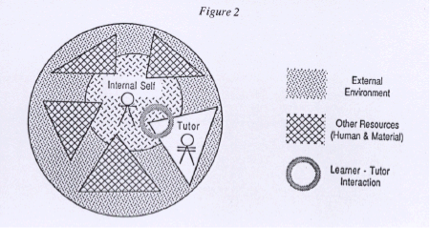

The model has the learner as central focus. In my practice this means considering issues for the learner before issues for the instructor or issues related to course content. Over the length of a course, the internal self of the learner is always interacting with an external environment. Some of the elements in that external environment are resources and interventions planned by educators. Other elements still impact on the learner, but are not under the control of the educators (See figure 2).

The learner interacts with resources in real and delayed time. An audio class is an example of real time (synchronous), a computer- conferenced class an example of delayed time (asychronous). Human resources include teacher, tutor, counselor, peers, family, expert, colleagues, and self, for many of our personal experiences are resources for learning. Some human resources are educators per se, others (librarians, colleagues) are educators by function. Material resources - conventional information packages, structured experiences, experiential learning episodes - are designed for different learning tasks under varying conditions. There will be times when the learner will want or need some pre-digested information in expository forms; at other times experiential and other inductive modes will be needed so that the learner can reflect upon events or analyze her/his own experience to generate personal implicit knowledge (Kolb,1984).

The learning tasks would be guided by a variety of teacher interventions, including behaviorist, cognitive psychology and humanist approaches, but used with a style that always respect the learner as an inherently proactive and responsible person. The teacher/tutor behaves as a genuine, respecting open person first and a content expert second. There is no denial of significance for her/him but there is a change in the rationale for that significance: the teacher becomes a facilitator as far as possible and uses transmittal, or highly controlling roles only as necessary. Authority and decision making are shared processes as far as possible. The course developers and tutors as facilitators recognize how the task and social aspects of learning interact, and have the skills to break down psychological distances between learner and facilitator. The facilitators have to decide the extent to which the learner may be helped to acquire “fishing rods’‘ and not just ‘‘fish” - the skills for critical and independent acquisition and use of knowledge. All things considered, the art and skills of facilitation call for a wide repertoire of high level skills. So much easier to “didact” !

This model is based on a holistic conception of the learner. Strang’s definition of a person-centred model is an appropriate one for this present model: “A person-centred model of learning focuses attention on the students as human beings. Rather than considering them solely as learning machines the model encourages recognition of qualities such as the propensity to adopt attitudes, to have intentions, and to make decisions’‘ (Strang, 1987, p. 27). The learner is assumed to enter a new learning situation with emotional baggage and earlier learning experience - some of which will be constructive for the new situation, some not. In many, if not all cases, the processes of learning may cause disequilibrium and some anxiety - sometimes hidden, sometimes not, sometimes projected or deflected into inappropriate behavior. Gender socializations, age, race, job, interpersonal relationships, education level, cognitive and affective styles, personal maturation levels, home life, etc. will also influence the learning processes. Given these conditions, the facilitator (course writer and tutor) has a tough task: she/he must somehow find an access point to ‘‘reach” the learner and establish a substantive rapport in order to help the learner expand her/his understanding. The usual process factors such as instructional interventions (Briggs, 1977) and provision of resources and conditions for dialogue, feedback and assessment of intended outcomes (Howard,1987) should be then matched, as far as possible, to the learner’s styles and needs.

Finding that access point may be done by looking at the learner through various screens. Each screen represents a developmental stage and/or a preferred style of “being in the world.” For distance education contexts, this process of getting to know the learner should become easier as interactive technologies are used more widely, and as our qualitative/phenomenological knowledge increases. But the substantive questions about learners are still as tough as they are for classroom contexts if we are serious about taking a learnercentred view of learning-teaching interactions.

How is the learner orienting to the learning experience? Is she/he trying to look for deeper meanings and interaction of concepts, or interested only

in recalling a mass of detail to get through an examination (Marton, 1984)? Where is the learner in terms of Perry’s scheme of cognitive and ethical development (Perry, 1981)? Many students in a course are likely to be at Position 1: “Gooo Authorities give us problems so we can learn to find the Right Answers by our own independent thought.” How do the course writers and tutors encourage development toward Position 5: “Everything is relative but not equally valid... Theories are not truth but metaphors to interpret data with. You have to think about your thinking.” The goal here is to help them move beyond dualistic thinking to relativistic thinking: how may this be done in the virtual classrooms (Hiltz,1986) of future distance education?

In terms of Schaie and Parr’s scheme of adult intellectual development (Schaie & Parr, 1981), how does a young tutor best help middle-aged learners at the Responsible or Executive stages use their learning to solve other people’s real life problems? How can older aged learners, in the same course, who may be at Reintegrative stage, be helped to refine and further construct their select meanings? And how does that same young tutor best interact with her/his sim aged young Achieving stage learners who have clear but often ego-centric life goals to accomplish? Does the reduced visual contact between students actual nelp tnis learner-specific work for the course tutor, or does it deny students the opportunity to see or feel how other people operate in the world? .

In terms of Loevinger’s stages of ego development (Loevinger, 1976), a course writer or tutor may want to nurture further movement through the stages, she/he has to provide a range of learning experiences and new responses, reduce the inevitable stresses and blocks to learning and facilitate the learner’s sense ol real achievement: how is this best done in the reduced cue environment of many distance education contexts?

Great differences exist in how people perceive, organize, and use information (Keefe, 1987; Huff, Snider & Stephenson, 1986; Even, 1987): how may a cours team ensure that at any given time in the course, learning tasks are matched to the cognitive and learning styles of at least one third of the learners, and that the other two thirds will use the preferred styles at other times? What criteria are most appropriate for assessing the quality of integration of learning methods?

Clearly the above questions will be tackled by course teams, tutors counsellors, librarians and others in different ways, depending on the nature of the course and on the styles, skills, and philosophical positions of those educators. Some educators may argue that it is not their job to be sensitive to ongoing adult development: ‘‘just tell ’em what they need to know.” Others will argue that the whole person is always involved in any process of significant learning: “knowing... as a process of engaging with and attributing meaning to the world, including self in it,” and the development of the “whole person, especially the continuing capacity to make sense of oneself and of the world in which one lives” (Boot & Hodgson,1987 p.6).

I lean toward the second orientation and therefore have had to develop my own facilitator’s “guide to the galaxy”; a way of putting my model into effect and giving me some criteria for assessing the quality of course designs. The following guidelines are, arguably, relevant to any context regardless of learner configurations, the type of interactive communications technologies used, and the learning goals. The facilitator’s guidelines are grouped into four R’s Responsibility, Relevance, Relatedness and Rewards: a set of concepts for a recast set of assumptions and key generic principles for learner-centred practice.

The learner and the facilitator have responsibilities - to themselves and to each other. The learner should be encouraged to feel and act responsibility - in planning, doing and assessing the results of their learning activity, and in their relationships with associates, e.g., peers and tutor. The facilitator’s responsibilities may be designated as:

This applies to content, process, past experience and learning outcomes. The facilitator needs to:

These operate in three dimensions. Interpersonal ones are the most obvious. Second is the integration of cognition and affect. Third is the relativistic and contextual nature of higher order thinking (Perry, 1981), and the learner’s personal relationship to knowledge. To foster these, the facilitator must:

Facilitators need to discuss with learners these potential rewards:

Much of this is radical stuff if you consider some of the alleged and actual constraints in distance education. But times past are not necessarily consistent useful guides for the future.

What do we need if we are at all serious about learner-centredness?

We need not so much an andragogical system as Coldeway defined it, one “which encourages and reinforces self directed learning” (Coldeway, 1985), but a neo andragogical approach - one that recognizes the realities of adulthood, not the myths. We need not so much self-directed learning as much as self responsibility for learning. We need not so much to admire the independence of learners as we need to facilitate the interdependence of learners and the collaboration of educators. We need not so much to protect traditional roles and skills of educators as to develop more facilitative ones and expand our notions of professional responsibility.

Atman, K.S. (1987). The role of conation (striving) in the distance learningenterprise. TheAmerican Journal of DistanceEducation, I,1, 14-24.

Ausubel, D.P. (1968). Educational psychology: A cognitive view. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Belensky, M.F. Clinchy, B.McV., Goldberger, N.R., and Tarule, J.M. (1986). Women’s ways of knowing: The development of self, voice and mind. New York: BasicBooks.

Boot, R.L., and Hodgson, V.E. (1987). Open learning: Meaning and experience.Chapter 1, In Hodgson, Mann and Snell, op cit.

Boud, D., & Griffin, V. (1987). Appreciating adults learning: From the learner’s perspective London: Kogan Page.

Brandes, D., & Ginnes, P. (1986). A guide to student- centered learning. Oxford: Blackwell.

Briggs, D.K. (1982). Adults’ recommendations for teaching/learning strategies and “andragogy’‘. Australian Journal of AdultEducation. 22,2,12-20.

Briggs, L.J. (Ed.) (1977). Instructional design: Principles and applications. Englewood Cliffs: Educational Technology Publications.

Brookfield, S. (1986). Understanding and facilitating adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Brundage, D., and MacKeracher, D. (1980). Adult learning principles and their application to program planning. Toronto: Ministry of Education.

Burge, E.J. (Ed.) (1984). Distance learning: Process and materials design. Proceedings of the First National Workshop of the Canadian Association for Distance Education (CADE). Toronto: C.A.D.E.

Coldeway, D.O. (1987). Behavior analysis in distance education: A systems perspective. The American Journal oJ Distance Education, 1,2,17-20.

Coltman, B. (1983). Environment and systems in distance counselling. Conference papers. International workshop on counselling in Distance Education. Cambridge: The Open University, pp.57-69.

Cranley, C.K. (1986). Guidelines for creating and supervising distance education courses. Sudbury: Centre for Continuing Education and Part- ime Studies, Laurentian University.

Cross, K.P. (1981). Adults as learners. San Francisco: Jossey- Bass.

Darkenwald, G.G. & Valentine, T. (1986). Measuring the Social Environment of Adult Education Classrooms. Paper presented at the Adult Education. Davenport, J. (1987). Is there any way out of the andragogy morass? Lifelong learning, I I ,3,17-20.

Davenport, J. (1984). Adult educators and andragogical-pedagogical orientations: A review of the literature. Journal of Adull Educalion, 12,2,9-17.

Davenport, J., & Davenport, J.A. (1985). A chronology and analysis of the andragogy debate. Adull Educalion Quarlerly, 35,2,152- 159.

Eichler, M. (1988). Non sexist research methods: A pnactical guide. Boston: Allen & Unwin.

Erikson, E.H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

Even, M.J. (1987). Why adults learn in different ways. Lifelong Learning. 10,8,23-25,27.

Fales, A.W. & Burge, E.J. (1984). Self-direction by design: Self- directed learning in distance course design. Canadian Journal of University Continuing Education, 10,1,68,78.

Farnes, N. (1975). Student-centred learning. Teaching at a distance, 3,2-6. Hartree, A. (1984). Malcolm Knowles’ theory of andragogy: A critique. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 3,3,203-210.

Henry, F., et Kaye, T. (1985). Le Savoir a domicile. Pedagogie et prolematique de la formation a distance. Quebec: L’Universite du Quebec/Tele- Universite.

Hiltz, S.R. (1986). The ‘‘virtual classroom’‘: Using computer-mediated communication for university teaching. Journal of Communication, 36,2,95-104.

Holmberg, B. (1986a). Growth and structure of distance education. London: Croom Helm.

Holmberg, B. (1986b). A discipline of distance education. Journal of Distance Education, 1,1,25-90.

Holmes, M.R. (1980). Interpersonal behaviors and their relationship to the andragogical and pedagogical orientations of adult educators. Adul Education, 3,10,18-29.

Howard, D.C. (1987). Designing learner feedback in distance education. The American Journal of Distance Education 1,3,24-40.

Hough, M. (1984). Motivation of adults: Implications of adult learning theoriesfor distance education. Distance Education, 5,1,7-23.

Huff, P., Snider., & Stephenson, S. (1986). Teaching and learning styles: Celebrating differences. Toronto: Ontario Secondary School Teacher’s Federation.

Inglis, P. (1987). Distance teaching is dead! Long live distance learning. ICDE Bulletin, 15,47-52.

Jacobs, E. (1987). Qualitative research traditions: A review. Review of Educational Research, 57,1,1-50.

Jarvis, P. (1981). The Open University unit: Andragogy or pedagogy? Teaching at a Distance. 20,20-21.

Jenkins, J. (1981). Materialsfor learning: How to teach adults at a distance. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Joyce, B. & Weil, M. (1986). Models of teaching (3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Kaye, A., & Rumble, G. (Eds.) (1981). Distance teachingfor higher and adult education. London: CroomHelm.

Keefe, J.W. (1987). Learning style theory and practice. Reston, VA: National Association of Secondary School Principals.

Kelly, M. & Shapcott, M. (1987). Towards understanding adult learners. Open Learning, 2,2,3-10.

Knowles, M.S. (1985). Andragogy in action. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Knowles, M.S. (1980). Modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy. (2nd ed.) (lst ed. 1970) New York: Cambridge Books.

Knowles, M.S. (1978). The adult learner: A neglected species. 2nd ed. Houston: Gulf.

Knox, A.B. (1986). Helping adults learn. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kolb, D.A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Lam, J.Y.L. (1985). Exploring the principles of andragogy: Some comparison of university and community college learning experiences. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 15,1,39-52.

Lindeman, E.C. (1926). The meaning of adull educaIion. New York: New. Republic.

Loevinger, J. (1977). Ego delveloprmenl: Conceptions and theories. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

MacKeracher, D. (1988). Personal conversation with author.

Maslow, A. (1968). Toward a psychology of being. New York: Van Nostrand. Marton, F. et al. (1984). The experience of learning. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press.

Melamed, L. (1982). Toward a conceptual understanding of the experience of play and playfulness in adult learning and development. Unpublished Ph.D.thesis, University of Toronto.

Mezirow, J. (1981). A critical theory of adult learning and education. Adul EducaIion (U.S.A.), 32,3-27.

Moore, M. (1986). Self-directed learning and distance education. Journal of DislanceEducaIion 1,1,7-24.

Nottingham Andragogy Group (1983). TowaIds a developmental theory of andragqgy. Adults: Psychological and Educational Perspective Series, No. 9. University of Nottingham, Dept. of Adult Education, Nottingham. Perry, W.G. (1981). Cognitive and ethical growth: The making of meaning. Chapt. 3 in Chickering, A.W. & Associates. The Moder n American College. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass,76-116.

Posner, G.J. & Rudnitsky, A.N. (1986). Course design: A guide to curriculum development for teachers,3rd ed. New York: Longman.

Pratt, D.D. (1988). Andragogy as a relational construct. Adult Education Quarterly, 38,3,160-172.

Rogers,Carl R.(1969). Freedom to lean. Columbus: Ohio: Merrill.

Roy-Poirier, J. (1986). The andragogical approach in graduate studies: Success or failure. Unpublished manuscript.

Ryan, D. (1987). The impermeable membrane. Chapter 17 in Student learning: Research in education and cognilive psychology. Ed. by J.T.E. Richardson, M.W. Eysenck, & D.W. Piper. Milton Keynes: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Schaie, K.W. & Parr, J. (1981). Intelligence. In Chickering, A.W. & Associates. TheModernAmerican College, (p.I 17-138). San Francisco: Jossey Bass. Smith, P. & Kelly, M. (Eds.) (1987). Dislance education and the mainstream: convergence in education. London: Croom Helm.

Strang, A. (1987). The hidden barriers. In V.E. Hodgson, S.J. Mann & R. Snell (Eds.). Beyond Distance Teaching - Towards Open Learning (pp.26-39). Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Taylor, E. & Kaye, T. (1986). Andragogy by design? Control and self-direction in the design of an open university course. Programmed Learning and Educational Technology, 23,1,62-69.

Taylor, S.J. & Bogdan, R. (1984). Introduction to qualitative research methods: The searchfor meanings, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley.

Tennant, M. (1986). An evaluation of Knowles’ theory of adult education. International Journal of Lifelong Education. 5,2,113- 122.

Willen, B. (1984). Self directed learning and distance education. Uppsala: Dept. of Education, University of Uppsala.

Woolfe, R., Mugatroyd, S., & Rhys, S. (1987). Guidance and counselling in adult and continuing education: A developmental perspective. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Yonge, George D. (1985). Andragogy and Pedagogy: Two ways of accompaniment. AdultEducation Quarterly, 35,2,160-167.