Distance Education in Social Work in Canada |

This article reviews the experience of Schools of Social Work in Canada in providing BSW programs through distance education. The experience of the School of Social Work at the University of Victoria is presented in some detail because of its lengthy and successful record in distance education.

In view of the paucity of accepted criteria to evaluate distance education programs, the authors developed a set based on standards used to evaluate social service and income security programs. Applying these criteria to off-campus programs yields the conclusion that distance education programs are effective and should be replicated.

Cet article passe en revue l'expérience des Ecoles de Service Social au Canada qui offrent des programmes menant au Baccalauréat de Service Social par l'éducation à distance. L'expérience de l'Ecole de Service Social de l'Université de Victoria est présentée en détail à cause de l'ancienneté et du succès de son programme d'éducation à distance.

Etant donné le peu de critères courants pour évaluer les programmes de formation à distance, les auteurs en ont developpé une série basée sur les normes employées pour l'évaluation des programmes de service social et de sécurité de revenu. L'application de ces critères aux programmes offerts hors campus mène à conclure que ces programmes de formation à distance sont efficaces et devraient être reproduits.

Twenty years ago it was not possible to obtain a distance education university degree in Canada. In fact, in 1972 the president of the University of Victoria resigned amidst a flurry of concerns about his mail order doctorate from an unknown U.S. institution. Distance education courses were commonly referred to as correspondence courses and available only for school age children in remote areas, or for shut-ins. Distance education was clearly viewed as a less desirable option to attendance at school.

The development of the Open University in Britain (OUUK) in 1979 was a milestone in distance education. The high quality of courses, the direct challenge to educators concerning teaching methods and the outstanding results (OUUK currently enrolls 74,000 students) raised the status of distance education considerably, particularly when the British experience was repeated successfully in other countries. In Canada, distance education opportunities at the university level increased steadily during the 70s and 80s as universities attempted to reach an expanding number of older students, primarily women, and respond to the need for ongoing education caused by rapid technological changes. This strength is illustrated in the development of at least three open universities in Canada (Rothe, 1987), the rapid expansion of dual mode institutions - those that provide both on- and off-campus instruction (Helm, 1987), a professional association of distance educators, and a national journal. Most of these initiatives emanated from the western provinces and Quebec where vast geographical areas and sparse populations have required innovative approaches to higher education.

The term distance education has several key ingredients (Keegan, 1983). Most importantly it refers to situations where teacher and student are separated by distance. Instruction is usually carried out through written course materials, audiovisual means, or more interactive approaches such as teleconferences and computers. It is usually aimed at adult students and encourages them to set their own learning objectives and proceed at their own pace. Distance education is delivered under some formal educational auspices and may or may not lead to credit, certificates, or degrees.

The authors surveyed all schools of social work in Canada by a mail questionnaire, with follow up interviews with those schools most intensively involved in distance education programs.1 This review suggests that there are very few courses and programs that meet the above criteria for distance education. However, several schools offer decentralized programs where degrees are obtained in satellite centres located at a distance from the main campus. Courses are usually taught in a face-to-face format at these centres by resident or travelling faculty. Decentralized satellite programs usually provide some avenues for local input into curriculum development and course delivery and generally encourage community ownership of the program. Some combine distance education and face-to-face methods and are, at least in part, distance education efforts. The term "off-campus" is used in this article as an umbrella term to include both distance and decentralized programs.

The first purpose of this paper is to examine briefly the developments in off-campus programs in social work and compare distance and decentralized approaches to delivery. Although similar efforts in other disciplines have been documented to some extent (Attridge & Gitterman, 1988; Rothe, 1987), this is not the case for social work. The second purpose is to identify strengths and limitations of the experience to date and suggest some possible guidelines for evaluation of distance education programs in social work and other disciplines.

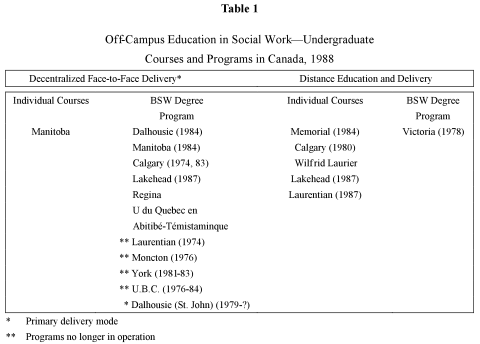

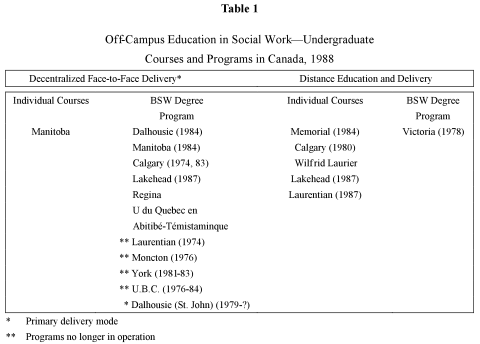

Table 1 summarizes off-campus courses and degree programs in Canadian schools of social work and their date of inception where possible. Given the paucity of off-campus graduate programs, we have included only baccalaureate courses and programs.

As indicates, most schools have invested their energy and resources in degree programs rather than individual courses. Of the six schools engaged in BSW programs, two are not really decentralized programs. The University of Calgary offers a BSW program in Calgary as well as in Edmonton and Lethbridge in cooperation with the University of Alberta and University of Lethbridge. In other provinces, such an arrangement may have resulted in three distinct schools of social work. The Université du Quebec has developed a system similar to U.S. state universities whereby semi-autonomous universities are linked together with an over-arching structure. Thus several schools of social work exist in different locations and one, Abitibé-Témistaminque, located in the northwest area of Quebec, has some out- reach programs.

In the other four schools (Regina, Manitoba, Dalhousie, and Lakehead) programs are offered in centres located apart from the main campus. The Manitoba school has a satellite in Thompson; Regina at Saskatoon and Prince Albert; Dalhousie at Sydney, Church Point, and Charlottetown, P.E.I.; and Lakehead at Kenora and Geraldton. Regina also offers courses in a variety of other locations depending upon student numbers and requests.

Schools report that these decentralized programs are valuable for two main reasons: they permit access for students who could not otherwise attend university and they enable the school to achieve a major goal of preparing social workers for practice in rural communities. Access for native students is particularly highlighted and the advantages of small student groups, close personal contacts, and faculty accessibility are noted as clear advantages of this model for such students. Several drawbacks of decentralized programs were also noted. Resource problems such as recruiting and retaining high quality faculty, library access, and high costs in travel were most frequently mentioned. Given the element of affirmative action in several of these programs, faculty costs may be considerably higher than in campus-based programs. Manitoba estimates at least 25% of faculty time is spent on such activities as counselling, special preparatory tutorials, faculty-led groups, study sessions, and assistance with papers and assignments. Administrative problems such as class scheduling, student advising and applying university regulations, and quality control issues such as monitoring student (and faculty) achievements were also noted as drawbacks. Several schools mentioned that the overall funding arrangements for such programs were particularly unsatisfactory. Most funding emanates from "soft" money sources, leaving programs very vulnerable in times of cutbacks.

Several schools have discontinued decentralized degree programs. Two schools reported that they closed down the program because the needs of a specific group of students had been met. Three indicated that programs were discontinued mainly because of inadequate resources and administrative problems. Clearly, the difficulties of persuading faculty from urban regions to travel regularly to rural areas, the lack of consistent funding for such efforts, and the problems of administering satellites at a distance have taken their toll.

Table 1 also identifies schools that provide courses and programs in distance education format. The five universities offering distance education credit courses (Memorial, Calgary, Wilfrid Laurier, Laurentian, and Lakehead) have taken somewhat different delivery approaches but most include some interactive component. Memorial offers two courses combining audiovisual, teleconferencing, and print- based materials; Calgary has pioneered the development of teleconferencing for several of its core courses in the BSW curriculum including one on interpersonal communication; Wilfrid Laurier and Lakehead use television for an introductory course in social welfare; and Laurentian has developed a print-based course.

Schools noted that distance education approaches were particularly useful for introductory courses. Such courses can reach large audiences, whetting academic appetites and attracting suitable students to the campus-based programs. Distance education has also helped some faculty members sharpen their teaching skills, given the public nature of some of their performances. However, there have been difficulties, including attracting faculty members to undertake such demanding and unfamiliar assignments, obtaining adequate resources for course development, and limiting student enrollment.

Since the University of Victoria (UVic) offers the only BSW program in the country that relies mainly upon distance education methods, the next section of the paper provides a more detailed description and assessment of this effort. Both authors were involved in the development and administration of the Victoria program and hence their opinions may be somewhat biased. However, where possible their recollections and views are supported by other reports and data emerging on the program after almost 10 years of operation (Clague, 1982; Canadian Association of Schools of Social Work, 1987).

The distance education degree program was introduced for two reasons: the mandate of the University of Victoria and the School of Social Work to serve rural areas of the Province and the availability of increased government funding for off-campus university programs in 1978. These additional funds resulted from a major inquiry into university education in 1976, the Winegard Commission, which argued the case for increased access to university education for students in non-metropolitan areas of B.C. This report paved the way for the Open Learning Institute (now the Open Learning Agency) as well as the establishment of University extension activities in the interior of the province (Winegard, 1976). The distance education program was introduced almost at the inception of the School of Social Work and was a crucial component of the School's early history (Haughey, 1985).

The majority of core courses are delivered through distance education, primarily print-based courses supplemented with audiovisual materials and telephone consultation with campus-based instructors. Students in remote areas of the province have easy access to these courses. However, two practice courses are offered only on a face-to-face basis and students must travel to a regional location to attend classes. Often these are delivered through weekend workshops taught by locally recruited faculty. An on-campus summer institute is now available for delivery of the face-to-face courses and is particularly useful for students in remote regions who have difficulty attending classes in winter. Students complete two practicum courses in their local communities arranged by a campus-based coordinator. Practicum assignments are set and graded by campus-based faculty who consult mainly by telephone with their students.

Although admission requirements are largely identical for both on- and off-campus students, the latter are expected to have at least two years of paid employment in the social services prior to entry into the program and preference is given to currently employed workers. This work requirement has resulted in a slightly older and more experienced group in the distance program. It was introduced for several reasons. Firstly, the faculty of the School of Social Work assumed that the best way to increase the numbers of trained workers in rural communities was to provide professional training to those already in the field, an upgrading program rather than one for novices or career changers. Secondly, faculty believed that practitioners would be able to relate the material in the distance courses to practice situations and thereby profit more from independent study than inexperienced students. Finally, the faculty hoped that the professional socialization function of the BSW may have been partly accomplished through work experience. These assumptions have proved fairly accurate, although other factors have emerged that have proved important to student achievement. These are discussed in a later section of the paper.

Students usually complete the BSW courses for their degree in 3 1/2 to 4 years on a part-time basis, often while holding down a full-time job. As students can choose the number of courses they take in a year and practica are individually arranged, they have considerable flexibility in planning and pacing their program.

At the inception of the program, the model of management was highly decentralized, partly because there were only two regions in the province involved in the program and partly because it was important to test community relevance and gain professional credibility. Regional coordinators and Community Advisory Councils provided local decision-making structures. Although the regional presence of the program has had clear advantages such as community ownership and credibility, increased professional presence of social work in the community, and support from crucial rural constituents when funding was threatened, there have been some disadvantages as well. These problems were similar to those experienced in other decentralized programs, and involved issues such as administration and quality control. Moreover, given the vast geographical areas and sparse population, it was not feasible to station local staff throughout the province.

When the School expanded the distance degree to include all areas outside the Vancouver-Victoria regions in 1986, it changed to a centralized management system. All administrative tasks are handled from the School, including admissions, practicum coordination, and student advising. A toll free line is available for students. Campus-wide support services such as book purchasing, library loans, admissions, and scholarships and bursaries are also carried out from the main campus.

In summary, the UVic program differs substantially from other off-campus programs in social work in Canada. It is primarily delivered through distance education methods, by a centralized faculty and administrative system to experienced students engaged in practice. It has not attempted to attract affirmative action students or career changers, to involve local instructors or community systems extensively in the delivery, nor does it rely heavily on face-to-face delivery.

There are several indicators that the distance education program has been successful in preparing baccalaureate students for rural practice. Admissions have grown steadily each year, from 35 in 1981 to 115 in 1987, with 63 graduates to date. The dropout rate is low and appears to be no different from most campus-based programs (Callahan & Rachue, 1988). Distance students achieve comparable academic grades and appear to have an equal commitment to the profession and a career in social work as their campus colleagues.

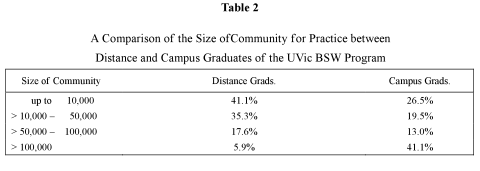

Although few major differences were found between campus and distance students in a recent study (Cossom, 1988), distance students tended to be employed more frequently in social work jobs, in supervisor or director positions, in full-time employment, in government service, and change jobs less frequently than their campus-based counterparts. They also tended to be more involved in broader community and social change efforts. Most importantly for rural social work practice, distance graduates were more likely to practice in small communities than their campus-based counterparts, as shown in Table 2.

Although the UVic program experienced its share of administrative difficulties, particularly in the early stages, it has prospered for several reasons. From the beginning, the Director of Extension assumed a leadership role in distance education in the Province and was a strong advocate for such developments at UVic. A review of the history of distance education at this University underlined the importance of his role and the alliance formed between him and the Director of the School of Social Work (Haughey, 1985). The School was the first on the campus to develop a distance professional degree program and hence enjoyed the benefits of a showcase effort. Further, the School of Social Work is part of a Faculty of Human and Social Development where four of the five schools have also developed distance programs. Over time, the Faculty of Human and Social Development has become a leader in distance education on the campus, a valuable reputation to have in a university dedicated to serving rural students.

Another crucial factor has been increased provincial funding for distance education in the past five years. As a result, the School has received its budget requirement in most years. In fact, the budget for delivery of the distance education BSW has grown from $129,758 in 1981–82 to $256,000 in 87–88, while course redevelopment and maintenance usually requires $50,000– $60,000 per year. (Even at these amounts, it is still less expensive to deliver distance programs than campus-based ones.)

Most importantly, however, the features of the program itself have been responsible for much of its success. One crucial factor has been the response of the other university departments in developing effective systems for distance education students. In particular, the library has developed a telephone service, Infoline, whereby students can call for references and assistance, and materials are sent directly to them (Slade, nd). In addition, the development of a core curriculum taught by the same faculty has resulted in a generally held opinion that the distance program is as rigorous and relevant as the campus-based one. It has also limited the number of courses that have to be developed and revised for distance delivery.

Probably the most significant reason for the success of the program has been the calibre and commitment of the students. All students have at least 30 transfer credits from university accredited courses with at least a B-average (many have a degree) and thus have demonstrated academic competence. Some have also succeeded in other distance courses and have experience with the demands of independent study. The modest research in distance education has indicated that student performance in previous distance courses is one reliable indicator of success in further studies (Coldeway, 1986).

The dedication of these adult learners has been apparent from the outset of the program. The basic reason is, of course, that most distance students have no other option to obtain a social work degree except through distance learning. The vast majority are women, 80% compared to 73% on-campus graduates, and many are employed with family responsibilities. However, one might expect that the formidable task of tackling largely print-based courses on their own would discourage the most committed students. Instead, it appears that the distance courses offer an opportunity for some adult students to feel in charge of their own learning and to proceed at their own pace within specific deadlines. Further many comment that the course content and assignments have greatly enriched their understanding of their community and day-to-day work. Many students, as mothers and active community members, have never taken time to do something for themselves and view their studies as a valued opportunity for personal and professional growth.

From the University of Victoria experience, the formula for a successful distance education program is similar to any other educational innovation: a program that meets the objectives of the school and larger institution, allows access to sufficient and reliable resources, and earns plaudits from all constituencies: students, professionals, other academics, and funders.

Most off-campus programs in social work, decentralized and distance, have grown haphazardly in response to student need, school goals of rural practice, and the commitment of a few faculty members. Very little has occurred in the way of collaboration between schools or evaluation of the efforts to date. However, given the extent of the experience in off-campus courses and programs in social work it is timely to begin some assessment. Such assessment should also help resolve the uncertainty in the minds of many academics, administrators, and students about the value of these programs and their future. On the one hand, they represent the best of social work values: providing access to disadvantaged consumers. On the other, there is some concern, often implied rather than stated directly, that they may diminish the quality of a discipline struggling to find acceptance in the mainstream of academic life.

To the authors' knowledge no criteria have been established to evaluate off-campus, particularly distance education programs. In view of this gap the authors turned to the literature on the evaluation of programs in social welfare. The standards listed below rely heavily on the work of Winnifred Bell (1969), while also responding to questions raised most frequently about off-campus education in social work.

The final section of this paper applies these criteria to off-campus, social work degree programs and raises questions for further inquiry.

Off-campus social work programs appear to be successful in reaching specific target groups: practitioners, rural residents, women, parents, and natives. Not surprisingly, distance programs are preferred to decentralized ones for remote students and those with home and work responsibilities. All off- campus programs face tension between attracting the best students from an academic and practice point of view and serving disadvantaged groups. Decentralized programs may have more difficulty in this regard. As they become more embedded in the community over time, the numbers of appropriate students may actually decline, particularly in the small communities of rural and northern Canada. In turn the desire to preserve the satellite may become an objective in and for itself and students with less than satisfactory records encouraged to attend.

From the responses to the questionnaire it appears that schools have not kept track of completion rates. Some indicated that it was their impression that there is a high drop-out rate amongst first time students in decentralized programs. This may be more related to the student population than to the decentralized nature of the program itself. The study on drop-outs in the UVic program indicates that few students left the program once admitted and that motivation was the key ingredient influencing completion (Callahan & Rachue, 1988). Such factors as gender (women were more likely to graduate than men), unemployment and underemployment were more important to degree completion than previous degrees, experience with distance education, or sponsorship by employers.

A major objective of most off-campus programs is to enable students to remain in rural communities and the study referred to earlier suggests that this objective is achieved with the UVic program (Cossom, 1988). Another UVic study is now underway to determine which distance students are most likely to remain in the community and find employment as social workers. Although most UVic students have present or past social work experience some of those who have excelled in the program have been admitted as exceptions. Some are mid years community leaders and volunteers. Others have worked in the past in teaching and related professions and have taken time out to raise their children. Their attachment to their local community seems to be the most accurate predictor of future rural practice.2 Further study is required to identify those students likely to complete decentralized and distance programs and the reasons why others drop out.

Fears that off-campus programs may be second class are frequently expressed. The reasons include the all too frequent use of sessional lecturers, the weaker academic background of some off-campus students, the restricted access to library, and the difficulty of maintaining the long academic tradition, particularly in social work, which emphasizes personal contact and modelling to develop communication skills and a sense of professional self. The marginal reputation of so-called mail order degree programs has not helped build the reputation of off-campus programs.

Schools of Social Work have undertaken various measures to ensure quality. Distance education courses are usually printed, televised, or taped and are thus even more open to scrutiny than campus-based courses. Campus-based faculty can also develop and deliver such courses. Decentralized programs may offer more personal contact and modelling opportunities than on-campus programs. The use of itinerant campus faculty can also ensure equity. Several decentralized programs where academic admission standards are lower than on-campus have hired tutors and offer accompanying study skill programs. The UVic program has established admission standards that exceed those of the campus-based program.

However, in reality most distance education students will not have much contact with face-to-face instruction or many full-time campus teachers. Are they adequately socialized to the profession by distance? Can critical thinking skills, often thought to be best developed through discussion and supportive challenge, be developed through distance learning approaches? Although UVic has attempted to meet these challenges by admitting practitioner students with a substantial academic background, it appears that others can similarly succeed in distance programs. What are the crucial variables? In decentralized programs, is it realistic to rely on itinerant faculty? Many cannot maintain the pace nor develop important relationships with the community. If not, how can quality be maintained with isolated, often inexperienced instructors?

One of the interesting aspects of the above questions is that very little has been done to define and test for professional socialization in campus-based social work education. Much of what happens operates mostly on faith. The one study the authors were able to uncover comparing the levels of professional socialization between on- and off-campus students in a social work program indicated no differences between the two groups (Patchner, Gullerud, Downing, Donaldson, & Leuenberger, 1986).

Another equity issue that requires exploration is the impact of off-campus programs on their campus-based counterparts. All the schools of social work that offer off-campus programs are dual mode institutions, that is, they have on-campus programs as well. To what extent do off-campus programs benefit or detract from campus-based ones? At UVic the growth of the distance programs has led to a well-defined curriculum but also to an increase in sessional faculty in both on- and off-campus programs. There are also questions about the use of distance education materials in the classroom. How are they best used, if at all? If not, can equity be assured?

It seems axiomatic that the more diverse the target group, the more adaptable the program must be to meet the needs of this group. As noted earlier, most off-campus programs attempt to reach a wide variety of students in populated as well as remote areas, with much or little academic and practice experience and frequently from native cultures.

Experience to date suggests that decentralized and distance programs may be applicable for certain groups of students and not others. Face-to-face decentralized programs may be most appropriate for students such as natives and those without a history of attendance in university programs. They provide small intimate learning experiences with potentially fewer pressures of university life. In addition, the curriculum can be modified on the spot to reflect the cultural and social values of the learners (Hudson, 1987). These programs are less suitable for really remote students who may find the frequent travel to the rural learning centre more onerous than one time travel to a university.

Distance education appears most suitable for experienced adult students with related work experience, a sound record of academic achievement at a university level, and high motivation. Nevertheless UVic students report that they are most satisfied if they can combine distance learning with some contact with other students and faculty. Some students develop learning networks and support groups in the face-to-face course, which sustain them through the distance courses. Others make repeated use of telephone conferences with faculty tutors or attend summer institutes on-campus. Only a few go it alone.

The central problem in adaptability in distance programs is the cost and time of course development and, consequently, the difficulty with tinkering with packaged course materials. On the other hand, decentralized programs may be so adaptable that they soon lose connection with their parent program. To deal with these realities, the ideal off-campus program may contain a mix of delivery modes including face- to-face instruction in regional centres for skills-oriented courses and inexperienced students, self-study packages in both print and video for remote and/or experienced students, and campus-based instruction for those wishing to speed up their degree and/or experience campus life for some portion of their program. However, ideal programs are, by definition, expensive. Faced with constant or declining resources, schools may have to decide whether to serve disadvantaged students via decentralized programs or more experienced students by distance education.

The smooth operation of off-campus programs appears to relate to several factors: the importance of the program to the school (a mainline or marginal effort) and the degree to which the larger university is committed to modify its administrative systems and policies to meet the needs of off-campus programs. Further, it appears that decentralized programs present more administrative challenges than centralized, distance programs, particularly in terms of staffing, student tracking, policy development and implementation, and evaluation.

This variable is the easiest to evaluate from the present survey. Almost all schools reported insufficient, unpredictable funding. Decentralized programs have been more vulnerable to funding cutbacks than the one distance program. It may be that satellites are highly visible, seemingly independent operations and their constituency has less access to campus-based decisionmakers. Distance degree programs with students in different stages of completion are popular politically and more likely to be viewed as integral parts of a total school program. The UVic program has also been protected by university and government policies that support distance education.

There may also be a perception that substantial and continuing funding is not required for off- campus programs because they are regarded as temporary and because funds for buildings and full-time faculty are not immediately required. Moreover, many schools began such programs as trial ventures and had no idea of longer term costs. For instance, UVic School of Social Work did not make the initial case for additional full-time tenure track faculty on the assumption that once developed, distance education courses could be handled on an overload or sessional basis. This has meant that while the program has been adequately funded in many ways it has relied increasingly on the use of sessionals and part-timers in both the campus-based and distance program.

Applying the above criteria to off-campus programs suggests some directions for future developments in social work and perhaps other professional programs. Decentralized programs have been more popular than distance education, probably because they fit squarely with the social work values of student participation, community control, and the academic traditions of face-to-face teaching. Further, they have the flexibility that is required for affirmative action programs. Yet they also have been short- lived. Some have been discontinued because they have fulfilled their mandate. Others have experienced administrative difficulties, funding shortages, and equity or target efficiency problems. Although the UVic distance education program meets many of the criteria and has successfully survived a decade of delivery, it has not been repeated in other provinces. There may be several reasons for this including its incompatibility with social work traditions and the requirement for innovative teaching approaches. The somewhat ironic conclusion is that programs that are compatible with academic and social work traditions have been less than satisfactory, but programs that violate these traditions and are successful have not been replicated.

Nevertheless, there is a clear need for distance education programs. In spite of the University of Victoria's efforts, there are a large number of rural workers in rural communities in B.C. without baccalaureate education. Recent figures published by the government ministry employing the most social workers indicates that 39% of front line social workers in the Greater Vancouver and Victoria areas have a MSW or BSW degree, while only 25% are similarly qualified in the rest of the province. In the north, only 18% of social workers have professional degrees (Carter, 1987). In Manitoba, when the School of Social Work opened its Thompson Program, 170 students applied for 15 positions. Presumably similar shortages exist in remote areas of other provinces. However, provincial jurisdiction of university education makes the task of replicating successful ventures very problematic. In addition, few articles and reports on off-campus education in social work have been published. Perhaps this article will begin to establish the case for distance education in social work on the grounds that it has potential for meeting one of the most serious and longstanding needs in the social services - the need for professionally prepared personnel in rural and remote communities.

1. The authors sent a questionnaire to 22 schools of social work in Canada with BSW degree programs in June, 1987. Seventeen responded. Of the remaining five schools, four did not appear to have any off-campus programs from a review of the CASSW directory of schools of social work and the fifth school was in Victoria, where both authors are employed. The questionnaire asked basic descriptive data about the off-campus programs and a brief assessment of strengths and difficulties. The authors also held follow-up interviews with faculty members from several schools most involved in off-campus education and sent a copy of the draft text to those schools.

2. The differences between these two groups may bear some similarity to Merton's classic comparison (1960) of "Local and Cosmopolitan Influentials." In Merton's study of Rovere, locals were those who have lived in the community for a long time and were committed to remaining there, who had a wide network of friends and contacts, and emphasized quantity before quality of relationships, who joined service clubs firstly for their social function and aspired to positions of local, political influence. Cosmopolitans, on the other hand, were more transient and viewed a move from Rovere as a distinct possibility, had fewer but more intimate friends, and joined organizations primarily to achieve goals. Although this study was carried out forty years ago, primarily with rural male influentials, it would be interesting to explore the extent to which students who remain in the community after they graduate are locals desiring a more cosmopolitan perspective but essentially committed to local endeavours.

Attridge, C., & Gitterman, G. (1988). Continuing education in nursing practice. In A. Baumgart & J. Larsen (Eds.), Canadian nursing faces the future (pp. 363–379). Toronto: C. V. Mosby.

Bell, W. (1969). Obstacles to shifting from the descriptive to the analytical approach in teaching social services. Journal of Education for Social Work, 5, 5–13. Council on Social Work Education.

Callahan, M., & Rachue, A. (1988). A comparison of drop outs and graduates from a BSW distance education program. Paper presented at the Canadian Association of Schools of Social Work, Learned Societies Conference, University of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario.

Callahan, M., & Whitaker, W. (1988). Off-campus practicum in social work education in Canada. Paper presented at the Canadian Association of Schools of Social Work, Learned Societies Conference, University of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario.

Canadian Association of Schools of Social Work. (1987). Report. Accreditation Team, Board of Accreditation, Ottawa.

Carter, R. J. (1987). Figures provided by the Ministry, letter to the authors.

Ministry of Social Services & Housing, Victoria, B.C. Clague, M. (1982). An examination of decentralized social work education in British Columbia. Final report sponsored by the Schools of Social Work at the Universities of British Columbia and Victoria.

Coldeway, D. O. (1986). Learner characteristics and success. In I. Mugridge & D. Kaufman (Eds.), Distance education in Canada (pp. 81–93). London: Croom Helm.

Cossom, J. (1988). Generalist social work practice: Views from BSW graduates. Canadian Social Work Review, 5, 297–315.

Daniel, J. S., & Stroud, M. A. (1979). Distance education: An overview. In F. W. Clark, A. Farquharson, & H. K. Baskett (Eds.), Developing outreach and competency based methods in social work education (pp. 12–19). Calgary, Alta.: Faculty of Continuing Education.

Haughey, D. (1985). Organizational adaptation in a university extension division. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Victoria, Victoria, B.C.

Helm, B. (1987). Distance learning via satellite in Canada. Paper presented to the Canadian Satellite User Conference, Ottawa.

Hudson, P. (1987). Correspondence. Director of the School of Social Work, University of Manitoba to the authors.

Keegan, D. J. (1983). On defining distance education. In D. Stewart, D. Keegan, & B. Holmberg, Distance education: International perspectives (pp. 6–33). London: Croom Helm.

Merton, R. K. (1960). Local and cosmopolitan influentials. In R. L. Warren (Ed.), Perspectives on the American community (pp. 251–256). Chicago: Rand McNally.

Patchner, M. A., Gullerud, E. N., Downing, R., Donaldson, J., & Leuenberger, P. (1986). Socialization to the profession of social work: A comparison of off-campus and on-campus M.S.W. students. Paper presented to the Symposium on Part-time Social Work Education, pp. 1–22. Miama.

Rothe, J. P. (1987). An historical perspective. In I. Mugridge & D. Kaufman (Eds.), Distance education in Canada (pp. 4–22). London: Croom Helm. Slade, A. (nd). Thirteen key ingredients in off-campus library services: A Canadian perspective (pp. 1–20). Unpublished paper, University of Victoria, Victoria, B.C.

Slade, A., Whitehead, M., Piovesan, W., & Webb, B. (nd). The evolution of library services for off-campus and distance education students in British Columbia (pp. 1–19). Unpublished paper, University of Victoria, Victoria, B.C.

Winegard, W. D. (1986). Report of the commission on university programs in non- metropolitan areas. Vancouver, B.C.