Investigating Instructional Approaches in Audio-Teleconferencing Classes |

This paper reports on the use of a system for analyzing audio-teleconferencing instructional sessions. The system (SATA), which analyzes the inter-actions that take place in audio-teleconferencing, was used to examine six university credit courses.

The courses, delivered by the teleconference network of Memorial University of Newfoundland, differed in level, discipline, use of supplementary media, and a number of other variables. The results of the study indicate the potential of SATA for depicting the instructional approach used by the instructor in an audio-teleconferencing class.

Cet article traite de l'usage d'un système pour l'analyse des cours présentés par audio- téléconférence. Le système (SATA) analyse les interactions qui ont lieu au cours des téléconférences et a été utilisé pour examiner six cours universitaires avec crédit.

Les cours, produits par le réseau de téléconférence de Memorial University de Terre-Neuve, différaient aux points de vue des niveaux, des sujets, de l'emploi de media supplémentaires et d'un certain nombre d'autres variables. Les résultats de l'étude démontrent le potentiel du SATA pour décrire l'approche éducative employée par l'enseignant dans une classe donnée au moyen de l'audio- téléconférence.

Distance education is assuming increasing importance in university settings across Canada and, at the same time, audio-teleconferencing is assuming a greater role in university distance teaching. Secondary school systems are also showing an interest in both distance teaching and in teleconferencing. For example, the Department of Education in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador is trying to provide high school students attending small, rural schools with more course options by using distance teaching. It plans to use teleconferencing - a real-time, two-way audio communication system - as a major mode of course delivery. However, to date there has been very little research into teleconferencing as an educational milieu (Kirby & Boak, 1987). Without such research, administrators are left to plan courses on the blind faith that they will work while instructors proceed to teach without the benefit of systematic knowledge of the instructional characteristics, potential, and limitations of the medium.

This study is part of an ongoing research programme to investigate a proposed model of instruction (Crocker, 1985) adapted for a multi-site teleconferencing situation. The research reported in this paper was designed to refine and test SATA (A System for Audio-Teleconferencing Analysis), which analyzes the interactions in teleconference teaching, and to begin a process of delineating the instructional approaches used in audio-teleconferencing classes.

Audio-teleconferencing may be described as two-way voice communication between three or more people in separate locations using standard telephone type technology (Keough, 1987). In university courses taught by distance education, teleconferencing offers a real-time linkage of the professor and students who may be scattered singly or in small groups across a wide geographic area. Teleconferencing has the potential to be a highly interactive educational medium in which it is possible for students to communicate with their peers in other locations as well as with their instructor. In the teleconferencing system utilized in this study, instructors usually transmit from a studio and use open microphones, although it is possible to transmit from any location using a standard telephone. Students go to designated teleconference centres and depress a bar on their microphones to transmit their voices to other sites on the teleconference circuit.

The System for Audio-Teleconferencing Analysis (SATA) was developed and tested initially in a pilot study at Memorial University. The teleconferences themselves were from a multimedia Women's Studies off-campus credit course offered by the School of Continuing Studies and Extension in the Fall semester of 1986. The course also included pre-packaged print, video, and film components. On the basis of the pilot, it was determined that SATA is a workable, comprehensive coding system that yields reliable data after a relatively short training period for coders. Compared to other observation techniques, the procedures are unobtrusive and relatively inexpensive. Because events are recorded, timed, and can be replayed, there are built-in safeguards against observer selectivity and observer omission of fleeting events. The types of data yielded by SATA enable a better understanding of the interactions taking place within courses and allow investigators to determine the direction and types of utterances, the proportion of the class time they occupied within sessions and over the length of the course, and the context in which utterances occurred.

SATA has its roots in the tradition of observational research and grew out of the classroom work of Stallings and Kaskowitz (1974). In particular, SATA classifies verbal interactions and constructs interactional sentences which denote who initiated speech, to whom they spoke, what was the nature of the speech, and the context in which the speech occurred. (For a detailed description of the SATA coding system see Kirby and Boak, 1987.)

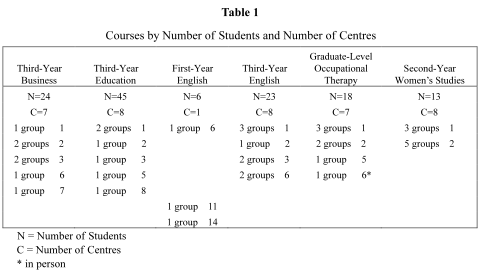

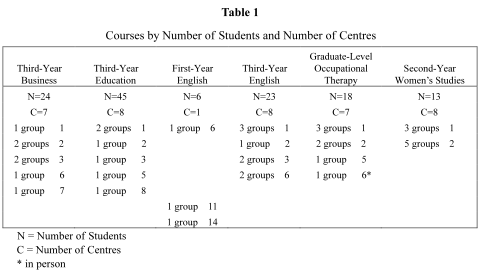

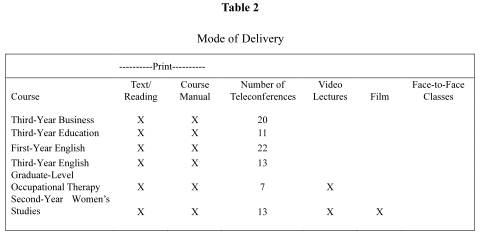

The teleconference tapes from one graduate and five undergraduate courses were coded and analyzed. Information about the courses is summarized in Tables 1 and 2. The courses differed in terms of level, discipline, method of delivery, size of class, number of teleconferences, number of sites, and size of teleconference groups at the sites. No attempt was made in this study to control for any of these variables. It will be apparent that some professors built a greater variety of delivery modes into their courses. Most relied on print, which must be prepared and distributed well before the beginning of the course, and audio- teleconferencing, which is a real-time communications system with the potential for spontaneity and interaction.

During the pilot study the teleconferences were broken arbitrarily into beginning, middle, and end segments for purposes of sampling. This division was undertaken because of indications from the literature that such divisions did in fact exist in terms of the way that teleconferences typically unfold. A sampling technique was adopted whereby five 3-minute segments were chosen from each one-hour tape to represent one sample from the beginning of the teleconference, three from the middle, and one from the end. In each case, these segments were: minutes 1-4, 14-17, 28-31, 42-45, and 55-58. Within each segment, every verbal utterance was coded.

The sampling procedure was changed in this second exploratory study. Since little is known about teleconferencing as a teaching medium, it was felt that a procedure which sampled evenly over entire teleconferences without making a priori assumptions about their nature might reduce the risk of masking elements that had not been anticipated.

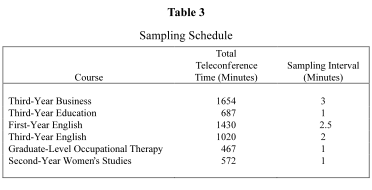

A proportional stratified sampling technique was adopted because the total teleconference time varied across the courses. The population of 5-second excerpts was calculated for the total number of tapes from each course. A sample was drawn so that for each proportion the margin of error at the point of the sample estimate was + or - .04 (p = .05). This margin of error was considered to be acceptable to fulfill the main objective of bringing forward any real differences in teleconferencing interactions that might exist between courses.

In practice, the adopted procedure resulted in sampling one 5-second excerpt from the courses according to the schedule in Table 3.

The class audio-teleconferences were recorded on audio-cassettes. These audio-recordings were subsequently transferred to half-inch video-cassettes along with a time code. Using a videotape playback machine, coders located pre-designated minutes on each tape and observed the start and stop times of utterances displayed on the monitor as they listened to them. The videotape machine allowed easy starting, stopping, reviewing, and fast-forwarding of the tapes with the time code in view, so that the coders could check their coding decisions or proceed to the next segment of the tape scheduled for coding.

Four university students were trained on the coding system for approximately 8 hours over a 2-day period. Practice involved using samples from the teleconference tapes that had not been designated for inclusion in the research. In calculating the reliability of coding, the decisions of all of the coders were compared over more than 300 coding decisions. Agreement was greater than 90%.

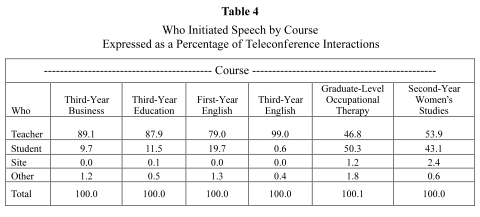

As might be expected, the majority of interactions in each course was initiated by the teacher, not the students (Table 4). There was, however, a considerable variation in the balance between teacher and student interaction amongst the different courses (Table 4). For example, in the Third-Year English course only 0.6% of the interactions were made by the students while in the Occupational Therapy and Women' Studies courses approximately 50% of the interactions were made by students. It would appear, therefore, that there are widely different degrees of interactivity between these courses. The remaining three courses, Business, Education, and First-Year English fell between these two extremes.

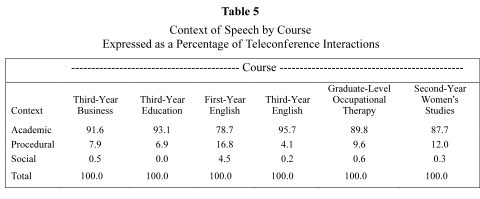

The data contained in Table 5 show the context of the interactions by course. As would be expected, the vast majority of the interactions were academic and considerably fewer concerned procedural and social matters. In the first reported use of SATA to analyze a course (Kirby & Boak, 1987), the proportion of time devoted to procedural matters was approximately one-fifth of the teleconference time. At that time it was recognized that this proportion was probably inflated as a result of the sampling technique used. The results in Table 5 tend to support this assertion since the time dedicated to procedural matters averaged over the six courses was 9.6%, and the Women's Studies course, which was the course used in the initial study, devoted 12% to procedural issues. Differences in the makeup of the courses, as well as differences in the students enrolled, offer possible explanations for some of the variation in the context of teleconference interactions. For example, the degree of course complexity, in terms of the number and different kinds of materials each contained, could influence the proportion of procedural interactions in the course teleconferences. For example, the Third-Year English course was the most unidimensional course studied. It can be argued that this course required few procedural interactions because it was relatively straightforward to run. In addition, this course, along with the Education and Business courses, was a Third-Year course. Thus the students enrolled could be expected to "know the ropes" and to require less direction than might be expected in a First-Year English course or Second-Year Women's Studies course.

Indeed, the greatest proportion of procedural interactions was found in the First-Year English class. This was not at all surprising since none of the students had any previous experience with university courses and lived in a community that was very isolated from the campus. Similarly, the Women's Studies course drew students from a variety of academic backgrounds and levels of experience. It also used more modes of delivery and involved more complex scheduling than other courses. Again, procedural matters might be expected to occupy a relatively large proportion of time.

A final example is Occupational Therapy, which was a fairly complex course, but one in which the need for procedural exchanges over the teleconference network probably was mitigated by the fact that many questions could be handled "off air" during two face-to-face weekend meetings between the distance students and their instructor. Students in this course were all graduates, which would lead us to expect a low need for procedural discussion. However, students varied in the nature of their undergraduate preparation, professional experience, lapse of time since their last formal study experience, and familiarity with distance education, with the effect that some students in the course required more explanations of the ways in which the course would operate than others.

Of the six courses reported in Table 5, only one, theFirst-Year English course, devoted any substantial time - 4.5% - to social interactions. It is interesting that this course was part of a Native and Northern Programme offered by the university to a small group of students located in one centre on the Labrador coast. Whether the nature of the course, the personalities of the participants, and the instructor or other factors were responsible for the degree of social interaction reported is worthy of further investigation. Indeed, the ways in which course, instructor, and student factors related to the context of interaction in general need to be studied in more detail and under more controlled conditions.

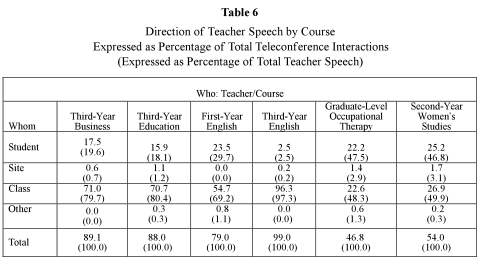

Considerable variety was observed in the patterns of teacher-initiated inter-actions (Table 6). In each case, the majority of the interactions were directed towards individual students and to the class as a whole with minimal amounts being directed to the Site or to Other "Whoms." There were, however, distinct variations among the courses as to how the interactions were apportioned between individual students and the class as a whole. There appeared to be three distinct groupings of courses. In the first group, comprised of Occupational Therapy and Women's Studies, the instructors spent approximately half of their time directing their speech towards individual students and half towards the class as a whole. A second group, in which 70–80% of teacher speech was devoted to the class and 20–30% to the individual students, was comprised of third-year Business, Third-Year Education, and First-Year English. Finally in one course, Third-Year English, virtually all the teacher speech, 97.3%, was devoted to the class as a whole.

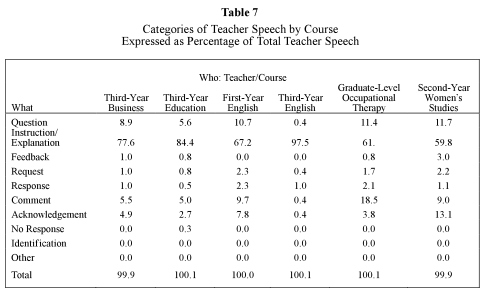

Teacher speech was classified using SATA into the categories shown in Table 7. The largest percentage of teacher initiated speech was Instruction and Explanation. Once again, the Occupational Therapy course and the Women's Studies course had very similar proportions and the Third-Year English course stood out as having virtually all of its interactions, 97.5%, falling in this category.

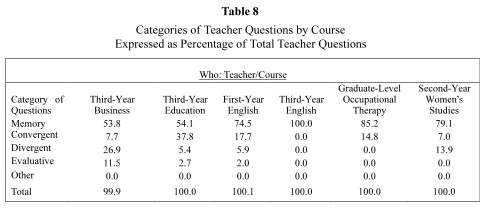

Three other categories of interactions accounted for nearly all the remaining teacher speech: questions, comments, and acknowledgement. Of these, probably the most significant from an instructional standpoint is the category of questions. SATA uses a scheme proposed by Cunningham (1971) to classify the questions into four groups: memory, convergent, divergent, and evaluative. The data in Table 8 show the percentages of teacher questions in each of these four categories. In each course the majority of questions involved direct recall and two of the courses included no "broad" divergent or evaluative questions at all (Cunningham, 1971). The Business course, and to a lesser extent the Women's Studies course, made use of a larger percentage of questions demanding answers at a higher level than simple recall. Also worthy of note was the substantially higher use by the instructor of the Women's Studies course of the interaction classified as acknowledgement, in which a response is recognized or agreed with. The teacher interactions in the Occupational Therapy course contained a noticeably higher percentage of comments than for the other courses. These were statements that were not classed as instruction or explanation and were not responses to a request, to a question, or to feedback.

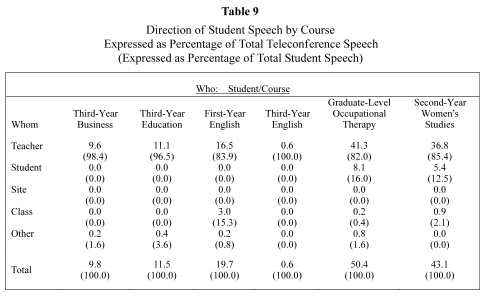

The most obvious feature of student initiated interactions is the lack of student talk in the Third-Year English course. Over 13 teleconference sessions, student speech in each accounted for less than 1% of the time (Table 9). Another prominent feature is the relatively small proportion of talk that students directed to other students. Despite the fact that student-student interaction is generally conceived of as a desirable feature of university classes, four of the six courses - Business, Education, and First-and Third-Year English - are alike in that there was no student-to-student talk over the teleconference system during class time.

Business and Education had corresponding proportions of student-toteacher speech, which accounted for a high percentage (98.4% and 96.5%, respectively) of total student speech. Teleconferences in First-Year English, as well as in Business and Education, contained a low percentage of student talk overall (19.7%, 11.5%, and 9.8%, respectively) so one must be wary of over-generalizing about apparent differences in the composition of their speech. With this caution in mind, one can speculate that the major difference in First-Year English is in the presence of some student-to-class speech, which has the effect of removing some of the predominance of the teacher that is found to such a great degree in the interactions in Business, Education, and Third-Year English.

As noted earlier, Occupational Therapy and Women's Studies were almost evenly balanced in the proportion of class time taken up by students and by teachers. In Occupational Therapy, student speech accounted for 50.4% of the teleconference time and in Women's Studies it occupied 43.1%. While more than 80% of the student talk was directed back to the teacher in Occupational Therapy and Women's Studies (82% and 85.4% respectively), 16% of student utterance time in Occupational Therapy and 12.5% in Women's Studies was directed over the teleconference system to individual students.

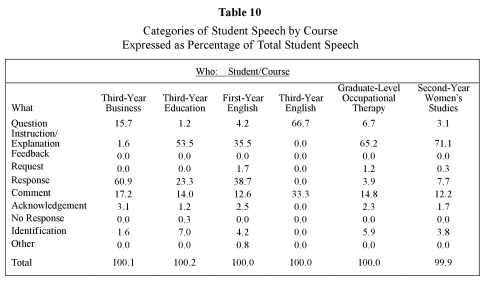

Bearing in mind that student speech accounted for less than 20% of the total in all courses except Occupational Therapy and Women's Studies, there are still differences that can be noted about the categories of student speech (Table 10). The exception is the Third-Year English course, in which little can be noted about categories of interactions because student speech was negligible. There was, however, a similar pattern for the Women's Studies and the Occupational Therapy courses and also for student interaction in the Education and First-Year English courses. The Business course appeared to engender a substantially higher percentage of student questions than the other courses and also contained a larger percentage of interactions classified as response than the other courses.

There were no utterances in any course initiated on behalf of the class, and Table 4 illustrates that utterances by "site" and "other" were negligible.

In summary, it appears that the six courses sampled in this study covered a spectrum of interactivity. The directionality of utterances in these six courses may be expressed as follows: Third-Year English was almost totally teacherdominated with virtually no interactions other than teacher-to-class. Business and Education were approximately 90% teacher-dominated, with 10% of speech from individual students, directed back to the teacher. There was some variation in the direction of teacher speech in these courses in that more class time and a greater proportion of the teacher's attention went to the individual students. This trend was more pronounced in First-Year English in which the proportion of teacher talk was less dominant, and within the teacher's speech there was again greater emphasis on individual students. Occupational Therapy and Women's Studies represented an even greater shift in the direction of sharing of time between instructor and students. This is reflected not only in the more equal split of total teleconferenced time between them but also in the way that teachers in those classes directed almost half of their speech to individual students, with the other half going to the class as a group. For the first time, one also finds students speaking to each other in these courses.

In all the courses discussed here, the most predominant category of inter-action was instruction or explanation, although in some of the courses student speech contained a substantial amount in the response category. In the Third-Year English course the very large percentage of time devoted to explanation or instruction, combined with the pronounced dominance of teacher interaction, depicts the instructional approach as being largely didactic. The Women's Studies and Occupational Therapy courses exhibited a lesser emphasis on explanation or instruction and a balance between teacher and student interaction and would appear to be more interactive in nature.

Since the inclusion of audio-teleconferencing in the various technologies available to distance educators is often supported on the basis of its interactive nature, the authors of this study were particularly interested in the use of questions in the teleconference sessions. The use of questions appeared to be somewhat limited in the observed sessions, occupying less than 10% of the total interaction in all courses. With the exception of the Business course, most of the teacher-directed questions were often of the "narrow" type (Cunningham, 1971), that is convergent or memory. It would be interesting to compare these observations with an analysis of live face-to-face instruction in the same courses. It would also be interesting to study the ways in which instructors achieved interactivity without employing direct questions, and whether indeed interactivity could be discerned as a goal of instructors during the teleconferences.

This paper is primarily concerned with testing a technique for observing the interactions that comprise the audio-teleconferencing classes and determining whether patterns of interaction that can be classified as instructional approaches exist within classes.

An analysis of the six courses sampled in this study indicates the potential of SATA for depicting the style of instructional approach used by the instructor. In one course the approach was clearly didactic and in two others the audio-teleconferencing medium appears to have been used closer to its full interactive potential. The remaining three courses fell between those two extremes.

As indicated earlier, this study was part of a larger study to investigate a model of instruction applied to a multi-side audio-teleconferencing system. Further work is concentrating on identifying and describing the antecedents of instruction and relating these to the instructional approaches of the teachers and in turn to relate these approaches to cognitive and attitudinal outcomes.

Crocker, R. K. (1985). The use of classroom time: A descriptive analysis. St. John's: Institute for Education Research and Development, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Cunningham, R. T. (1971). Developing question-asking skills. In J. E. Weigand (Ed.), Developing teacher competencies (pp. 81-130). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Keough, E. (1987). Course manual on the development of distance education. Unpublished manuscript, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Division of Educational Technology.

Kirby, D. M., & Boak, C. (1987). Developing a system for audio-teleconferencing analysis (SATA). The Journal of Distance Education, II(2), pp. 31-42.

Stallings, J. A., & Kaskowitz, D. H. (1974). Follow through classroom observation evaluation 1972-3 (SRI Project 7370). Stanford, CA: Stanford Re-search Institute.

David Kirby is a Professor and Dean of the Faculty of Continuing Education at The University of Calgary, Canada. His research interests include distance education and demographic and institutional research relevant to part-time university students.

Cathryn Boak is Manager of Telemedicine and Educational Technology Resources Agency at Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada and a producer with the Division of Educational Technology of the School of General and Continuing Studies and Extension. Her research interests embrace the areas of writing, distance education, and Women's Studies