Nurses' Experiences of a Distance Course by Correspondence and Audioteleconference |

VOL. 6, No. 2, 39-57

A qualitative research study was conducted to examine the experience, learning strategies, and reported learning of nurses taking a Nursing Issues course by teleconference or correspondence. Telephone interviews were conducted with 24 female nurses from distance post-RN programs at four Canadian university nursing schools. Two schools used a teleconference, group-oriented approach; another two used a correspondence-based, individually-oriented approach. The respondents were similar in many ways: demographics, motivation for study, learning approaches, and reported learning. Important factors in the students' reactions included: compatibility of learning style with teaching method; supports from family, employer, and peers; resources available in the community; and perceptions of the university attitude to students. Most students studying by each method were group-oriented in their approach to learning. Teleconferences encouraged group learning; although correspondence was more convenient. Most students were very teacher dependent despite the lack of direct contact. Often they were learning in spite of, rather than because of, the teaching method used. Most students in both groups reported changes in attitudes as a result of the course and the program and there is evidence that resocialization to professional attitudes occurred.

Ce projet d'étude qualitative passe en revue l'expérience, les stratégies d'apprentissage, et l'apprentissage reconnu d'infirmières qui ont suivi par téléconférence ou correspondance un cours sur des questions d'intérêt particulier aux sciences infirmières. Nous avons entrevu par téléphone 24 infirmières enrôlées dans des programmes post-certification à distance dans les écoles d'infirmières de quatre universités canadiennes. Deux écoles ont employé une approche de téléconférence par groupe; les deux autres une approche individuelle basée sur la correspondance. Les réponses révèlent de nombreuses ressemblances entre les deux groupes: démographie, motivation à l'étude, techniques d'apprentissage et apprentissage démontré. Les réactions des étudiantes comprenaient des facteurs importants: la compatibilité du style d'apprentissage avec la méthode pédagogique utilisée; le soutien de la famille, de l'employeur, et des collègues; les ressources offertes par la communauté; et les perceptions que ces étudiantes avaient de leur université envers elles. La plupart des étudiantes dans chaque méthode étaient orientées vers le groupe dans leur approche envers leur apprentissage. La téléconférence encourageait l'apprentissage en commun; la correspondance était plus pratique. La plupart des étudiantes s'appuyaient beaucoup sur l'enseignante, malgré le manque de contact direct. Souvent, elles apprenaient en dépit de la méthode pédagogique utilisée, plutôt que grâce à elle. La plupart des étudiantes dans les deux groupes ont rapporté que le cours et le programme ont mené à des changements d'attitude de leur part, et ont conduit à une ressocialisation des attitudes professionnelles.

Distance education and nursing education are joining forces to improve access to both continuing education and university credit courses for working nurses. As more and more nurses become involved in distance learning, it is important that nursing and distance educators assess the impact of these programs. The purpose of the study reported here was to examine the experience of registered nurses taking university credit courses in Nursing Issues by distance education. Some of the nurses attended group-oriented, audioteleconference classes; others took a similar course by individually-oriented, correspondence-based methods. The reports of the students exposed to each approach are examined for similarities and differences.

Canada has been a leader in the development of distance education (Burge, Wilson, & Mehler, 1984; Faith, 1989; Minnis, 1984; Mugridge & Kaufman, 1986). Universities, professional organizations, and other groups have used distance methods to reach learners scattered across the country. Nursing has been one of the professional groups that has used distance education extensively (Bailey, 1987a, 1987b; Cervinskas & Waniewicz, 1984; Charbonneau, 1982).

There is a movement in Canada to increase the number of baccalaureate-prepared nurses. In 1982 the Canadian Nurses Association passed a resolution calling for baccalaureate preparation as the requirement for entry to practice by the year 2000. Employers now are demanding degree preparation for an increasing variety of nursing positions. To accommodate the need for upgrading, post-RN degree programs have been developed for registered nurses who hold diplomas obtained from hospitals or community colleges. Building on a nurse's previous education, these programs include courses on the physical and social sciences and humanities, as well as nursing theory and practice. The goals of personal and career advancement have led many diploma-prepared nurses to seek post-RN degrees. Nurses throughout the country have been applying pressure to make these programs more accessible.

One of the ways universities responded to this pressure was to establish post-RN distance education programs. In doing so, nursing educators adopted methods already available for distance study, including print-based learning packages and teleconferencing (Carver & MacKay, 1986; Collins, 1982; DuGas & Casey, 1987). Different nursing schools, however, adopted different methods and approaches to teach similar material.

Nurses enrolled in post-RN programs tend to be highly motivated (Croft, 1987). Carey and Peruniak (1982) report that nurses enrolled in Athabasca University courses do very well. "They are achievement motivated, goal-directed and capable of imposing the self discipline necessary for distance learning. [In Introductory Psychology] they complete the course with the highest marks, in the least time and have the fewest dropouts" (p. 59).

However, things are likely to change. Croft (1987) predicts that

The nursing market is likely to be characterized by three overlapping waves. First, career- minded nurses are looking for opportunities now. Second, as the reality of the B.Sc.N. as the entry to practice approaches, a less committed group will become involved. Finally, if and when the B.Sc.N. is the entry to practice, nurses who do not wish to study but wish to retain career options will come forward. (p. 10)

At present, those studying at a distance are motivated and are willing to endure a certain amount of inconvenience, including learning environments and materials that are less than perfect. However, if Croft's prediction is correct, we may be moving toward a less committed group of learners who may be less able or less willing to benefit from ineffective materials and practices. It is, therefore, worth examining the experience of those presently in these programs to identify factors that increase student engagement and opportunity to learn. The experience of nurses as adult learners and women also may provide direction for distance educators more generally.

Two major approaches to distance learning have been identified (Barker, Frisbie, & Patrick, 1989; Calvert, 1986; Holmberg, 1983). One seeks to simulate the circumstances of the face-to-face classroom as closely as possible. Instruction is aimed at the group. Students interact with the instructor and with other groups of students via electronic links. Discussion, questions, and spontaneous interaction are all possible. Because all participants must be present at the same time, the time is fixed, just as it would be in a face-to-face classroom.

The other approach to distance education is aimed at the individual learner. Although students may choose to meet and study together, the underlying assumption is that the student works alone at a personally convenient time.

It seems reasonable to assume that the learning experience will differ with different approaches. The simulated classroom offered by teleconferencing has the advantages of direct peer contact and regular opportunities for interaction with faculty. Correspondence study, on the other hand, removes the constraints of time and place that nurses working shifts find so difficult. Issues of convenience aside, however, it is important to discover the factors that contribute most to a positive learning experience and whether students in professional courses are becoming professionally resocialized.

Concern has been expressed that distance methods may not be effective in achieving one of the objectives of post-RN education - the professional resocialization of post-RN students (Gray, 1980; Carey & Peruniak, 1982).

The traditionalists argue that only by having students physically together for a period of time, usually several years, can a sense of professional ethics and commitment to a particular philosophy of the profession be developed. On the other hand, there is the argument that such socialization can better occur if students are learning within their community and the organization in which they will be working. (Farrell & Haughey, 1986, p. 34)

Rogers (1986), however, reported changes in attitudes amongst students enrolled in courses in the health and social welfare sector at the Open University in Britain but concluded that these changes were dependent upon face-to-face group discussions included in the courses.

The purpose of this research was to examine the experience of students in post-RN baccalaureate nursing programs who were taking courses in Nursing Issues by distance methods, a course designed to help the student shift from a technical, hospital, and illness orientation to a more broadlybased, health- oriented, professional attitude to nursing.

The questions addressed were:

Qualitative methods were selected because the parameters of the phenomena to be studied were not identified clearly enough for quantitative analysis. Furthermore, the subjective reality of the student is important because it may provide insights into what promotes or inhibits learning.

Six students from each of four universities were interviewed by telephone. Each student had successfully completed a half course in Nursing Issues. Two universities used a group-orientated, classroom approach using audioteleconferencing. Two used an individually-oriented approach by correspondence supplemented with audio and video programs. Content of the courses was comparable across the four institutions. This sample allowed us to determine if group differences were attributable to the institution or the method.

The universities using group-oriented methods, referred to as Universities A and B, are in Eastern Canada. Both used audioteleconferencing techniques. One evening each week a professor met simultaneously with a group of students face-to-face and those in outlying locations. A telephone bridge linked the classrooms. Students had access to microphones that allowed them to be heard through loudspeakers in the other sites. University A had several distance locations, two of them within the same city as the university. University B had only one distance location, in a city some distance from the university.

The universities using correspondence courses are located in Western Canada and will be referred to as Universities C and D. Students were sent course outlines, a book of readings, and audiotapes. Video transmissions were broadcast by satellite and cable. The two universities used the same resources, but the course was used differently in the two curricula.

All students were interviewed by telephone using a semi-structured interview schedule. The telephone was used because students were scat-tered throughout the country, often hundreds of kilometres from their universities. Interviews lasted from 50 to 90 minutes. The interviews revealed a breadth of experience and sufficient commonalities and differences for major factors within and among the groups to be identified.

The interviews were friendly and relaxed, but it is possible that the informants were not as open as they might have been in a face-to-face discussion, especially about negative reactions to their respective programs. For this reason we suspect the telephone interviews provided data that was less rich than what might have been elicited in a face-to-face setting.

The interviews were taped, with the respondents' permission, and the transcripts were analyzed first to identify common themes. The strategies for coding and memoing of data outlined in Strauss (1987) and Miles and Huberman (1984) were used. The themes which emerged included advantages and disadvantages of distance education, supports and hindrances, learning, teacher perceptions and role, socialization, attitudes, and values. The learning theme file was broken down further into categories of strategies - teacher-directed, group-oriented, and self-directed learning. A set of codes reflecting the concepts discussed by the respondents was developed for each theme. Each theme file was then coded to identify statements referring to the topics, both negatively and positively. The results were then grouped and reported by theme and code. Responses from each university and both methods were compared.

Generally, there were more commonalities than differences amongst the respondents, regardless of institution or methods used. Topics, therefore, will be discussed generally and differences noted as they occurred.

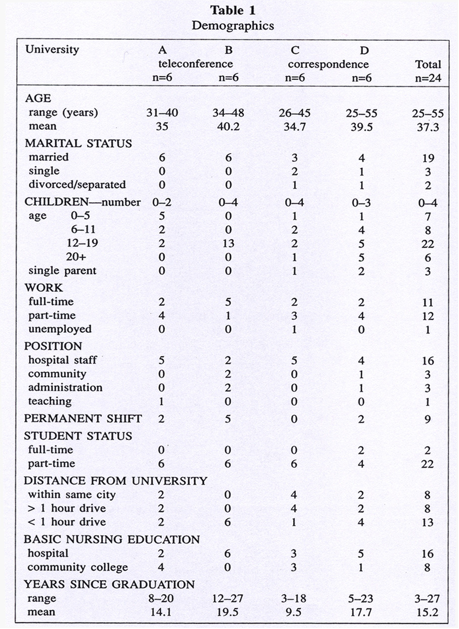

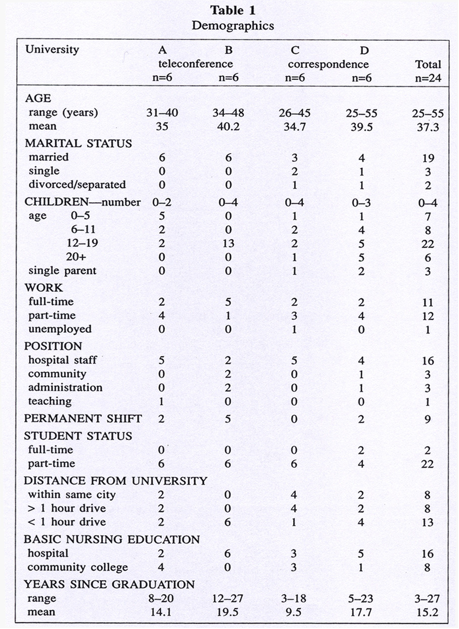

The demographics of the groups are outlined in and . All were women. Most were married and in their thirties. Most were working and most had children. In the teleconference groups there were more part- time and permanent shift workers. This may be because teleconference students were required to travel to the distance site once a week and because it is easier for part-time workers and day or night workers to attend evening classes regularly. The advantage of correspondence courses for nurses working rotating shifts is the ability to time-shift their learning. There were also two full-time students. One was taking a distance education course because it fit her on-campus timetable; the other was taking her whole program at a distance.

Many of the teleconference students were travelling long distances to attend class. Several of them drove for more than an hour each way to reach the regional centre, often encountering dangerous situations. One student reported that whenever a truck cut her off on the expressway she questioned, "Why am I risking my life for this?" Another group had an even more threatening experience when hit by a bus during a snow-storm. The teleconference students who chose not to drive across town to a face-to-face class placed great emphasis on convenience.

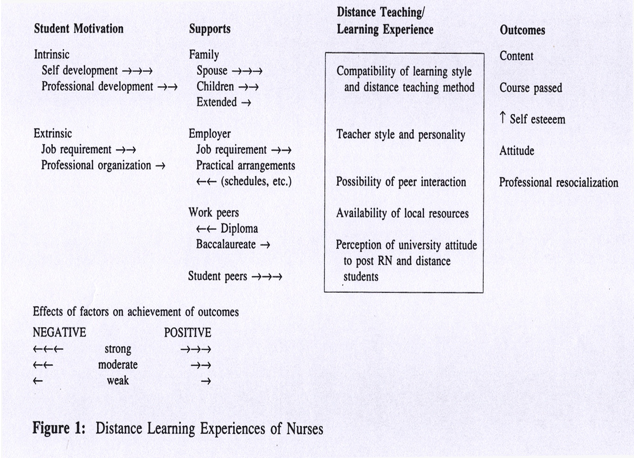

Eight of the 24 students lived within the same city as the university, demonstrating that distance education is not only a matter of geography. Some chose distance study because they did not like attitudes found the classroom. These women saw faculty as condescending and fellow students as having values they did not share. Therefore, they distanced themselves deliberately. The term second class citizen came up a good deal in the interviews, indicating feelings of political distance and lack of control over what happened to them as students. presents the interrelationship of factors identified in the student responses. It will be used to organize the discussion of the highlights of the informants' responses.

One factor that stood out throughout the interviews was how highly motivated these women were. They were making considerable sacrifices of time, effort, emotional strength, money, and family peace to achieve their degrees. None was considering dropping out. All were very proud of what they had accomplished. Intrinsic factors were by far the greatest motivators. Most respondents gave a number of reasons for enrolling in a degree program, but self-development was identified most frequently and usually mentioned first. One nurse who was driving two hours a night to a teleconference class said that she started the program because she needed "intellectual recreation." Another said, "I love to learn and you can only take so many courses in macramé." Respondents also reported wanting to join family members who had degrees, wanting their children to be proud of them, and wanting to set an example of life-long learning. Many were learning for the sake of learning and several talked about going on to Master's programs.

Many students also enrolled to develop professionally, one stating that she wanted to be the best nurse she could be. Because she felt inadequate in some areas of nursing, the degree was the way to acquire the knowledge and skills she needed. Two people in small centres acknowledged that professionally they had already gone about as far as they could in those locations but were continuing because they liked the self-development.

Students also cited extrinsic factors for enrolling in the program. Some had specific ambitions that required degrees. One, for instance, wanted to assume the position of director of nursing in the small hospital where she worked when the incumbent retired. Another wanted to become a head nurse in order to accomplish change in her institution. Three students, one involved in staff development, another who was director of nursing at a nursing home, and yet another who worked in community health, said they were in the program partly to qualify for the jobs they currently held. There was occasional mention of the entry to practice resolution and the realization that the degree was needed to get ahead, but these were seldom named as important motivators.

Though some students had specific intentions, most were vague about their ambitions. They used words like "unsure" and "maybe" when talking about what they would do when their degrees were completed. They mentioned jobs that require degrees, like teaching, administration, and public health, but only as possibilities.

Another factor in the students' experience of distance education was the support they received from various segments of their community. First and most important was the family. Spousal support was very important. Husbands encouraged their wives, typed papers, cared for the children, and provided emotional support. Only one of the respondents reported that her husband had not been supportive. Regardless of the support, however, there was resentment when the wife could not socialize on Saturday night because a paper was due or the laundry was not done. Interestingly, these women, as well as their husbands, expected that they would continue to fulfill traditional female roles in the home while working and studying. Nevertheless, the experiences of the women studied here support Campariello's (1988) finding that less role conflict occurred in returning post-RN students who had strong support at home.

Children's reactions were mixed. Younger ones resented the amount of mother's time that was taken up studying. The two single mothers of preschoolers found it necessary to send their children to daycare while they studied. Some mothers of teenaged children found it necessary to go to a friend's home, the office, or a library to get away from the noise and bustle at home. On the other hand, college-aged offspring were very encouraging, and two students had chosen a particular university because they had children at the same institution. Mothers were also proud to be demonstrating to their children a commitment to life-long learning. Some hung their marks on the refrigerator along with the children's and one family went out to dinner to celebrate whenever Mother got an A.

Extended family members were less influential, although they did help with tasks like child care, and relatives who were also nurses often provided encouragement. Often family members, however, could not understand why a nurse was going back to school to qualify for something she was already doing.

Employers presented problems, too. Some, especially those who required their nurses to have academic qualifications, were very supportive. However, it was felt that some employers were only paying lip service to the goal of having a degree-prepared staff. When it came to getting time to go to class or to write an exam, there could be problems. The individual attitude of the immediate supervisor was usually most important. If the manager were supportive, the student had few problems rearranging her schedule. If the supervisor was threatened or felt organizational constraints, students found their requests resented and thwarted. On the other hand, some employers were very helpful and provided exam proctors, sent letters of encouragement, organized support groups, and helped with tuition. However, until employers implement policies to help their nurses meet course requirements, employed post-RN students will continue to have difficulty.

Work peers were often discouraging. Many students found it better to downplay their student status and things they had learned in order to maintain good working relationships. They frequently encountered resentment and scepticism, especially from older diploma-prepared nurses. Some students, however, said their peers had been very helpful. They had taken on-call duty in specialty areas so that teleconference students could attend class. One correspondence student reported that when she brought her books to night shift, the nurses she worked with did tasks for her so that she could get more studying done. Other students had persuaded colleagues to enrol. In one small town with 24 nurses, two had degrees, eight were studying, and the rest were justifying their lack of participation. Studying had become the expectation.

Many nurses reported that because they encountered little understanding from those they worked with, they turned for support and stimulation to nurses who already had degrees or who were studying. School peers gave a great deal of encouragement and may have furthered the professional resocialization by providing the new peer group that is one of the factors in the socialization process (Lum, 1978). Fellow students also provided an important support network, especially for the teleconference students who saw people repeatedly in classes and commuted with them when travel was required. Although there was less contact for correspondence students, they sought others to help them with their learning. Correspondence students frequently reported that study groups were important to them, both for support and learning.

The students reported a variety of responses to distance learning. Most were pleased to have distance courses available to them. Had this not been the case, they would not have been able to pursue the degree or would have had to move to do so. Convenience was an over-riding factor for most of these busy women. Teleconference students chose to save half an hour driving time despite preferring face-to-face classes. The correspondence students liked being able to study when they were free, condense their studying time if they had to, and accommodate family crises without losing credit.

Several of the students reported frustrations with distance learning because of difficulties adapting to the constraints of distance education methods. They seldom spoke of learning styles, but it was possible to deduce some characteristics from the descriptions of the various approaches to learning. Several of the teleconference students complained about the lack of visual stimulation. For those who were not auditory learners, having to listen for prolonged periods of time proved difficult and they were easily distracted by other stimuli in the classroom. Some correspondence students reported feeling foolish when they spoke out loud to themselves, but they needed the auditory stimulation. The most frequently reported difference in approach to learning among the students was the need for teacher contact and group stimulation. Some students were happier studying alone and relating to written materials. Others knew they needed interaction with other students to have a meaningful learning experience. Their reactions reflect the learning styles identified by Booth and Brooks (1988). Based on Seagal and Horne's (1985) work, this theory identifies mentally-centred, relationally-centred, and physically-centred learners. The contention is that the majority of women are relational learners and, therefore, need a personal relationship with the teacher and interaction with others to sustain attention and involvement in the learning process. These learners need to relate their learning to their experiences and need opportunities to say aloud what they are learning in order to internalize new material. In teleconferences, some of these factors were available, although the teacher relationship was limited.

The correspondence students who needed group interaction to learn expressed their difficulties with the method most clearly. To compensate for the difference between the individually-oriented course and their group-oriented style, they sought out learning groups or members of the professional community to help them learn. When other students were not readily available, they went to considerable trouble to build other contacts.

Mentally-centred learners use the visual to stimulate learning. They focus more on the idea, theory, or data than on people. There were some teleconference students who felt that they could have done as well and been as happy with an individualized, correspondence course. Several of the correspondence students preferred that method because it did not place interpersonal demands on them and allowed them to interact with only the course materials. One said she liked her own ideas and didn't have the patience to listen to others. While this attitude would make an educator trying to change attitudes cringe, it meant that she and others like her prefer the individualism of correspondence courses. The more the method allowed the student to learn as she liked, the more satisfied she tended to be with distance learning.

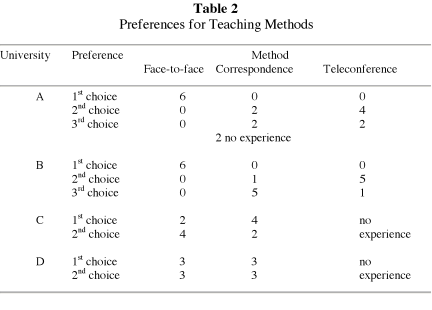

Students were asked which mode they preferred if other factors were equal (). None of the correspondence students had experience with the teleconference mode. All but two teleconference students had experienced correspondence learning and all students had experienced live classes. Despite the unanimous preference for live classes among the teleconference students, four students at University A who lived in the city or within an hour's drive of the university were taking teleconference courses. Distance was second best for them, but convenience was more important. Among correspondence students, there were those who preferred to learn alone or who felt that any advantages of the classroom were overridden by the ability to study to their own schedule.

Because most students had experienced a variety of courses taught by distance, they often referred to that experience in the interviews. Many felt that correspondence was particularly suited to courses requiring a great deal of memorization. However, for courses like Nursing Issues, where there are no right answers and individual opinions are required, the suitability of distance methods, especially correspondence, was questioned by the respondents.

Teachers loomed very large in the students' reports. They were dependent on the teacher for marks and had problems figuring out what was expected because they lacked the student grapevine and direct contact. The teacher's control of the content made her very important to the students. They were learning individually but not independently. It seems reasonable to assume that because the teachers determined whether or not a student passed, their opinions and emphases were eagerly assessed. The students were also very interested in what the professor was like as a person. The teachers, especially at universities A and D, emerged in the interviews as distinct characters. Even without much direct contact, students described them in considerable detail. This finding supports the work of Forsythe (1983) and Iman (1987) who claim that in distance education the human relationship with the students should be emphasized. The respondents very much appreciated professors reaching out by telephoning students or by visiting distance sites.

Other people, particularly classmates, were a very important learning resource. Nursing is a group activity in which practitioners expect to consult with others before implementing new ideas. Finding others to discuss these matters was particularly difficult for the correspondence students who had few fellow students in the same location.

The possibility for and the quality of discussion was a matter of concern in Nursing Issues. Even audioteleconference courses did not allow for the kind of discussion typically found in a face-to-face classroom. Nonetheless, discussion was encouraged and stimulated by the teachers, and several students reported that the teleconferences exposed them to points of view they would not have thought of themselves. However, the limited number of people at the distance sites and the feeling of being isolated from the main group detracted from the discussion quality. In the correspondence courses, discussion generally occurred only if students organized a study group. Some acknowledged that they chose to study with people who shared the same point of view, a decision that inevitably limits the range of discussion. Some who lived in communities where they were the only student deliberately sought out other nurses to discuss issues being raised in the course. Some pursued nurses with degrees or with strong opinions; others deliberately sought out people whose opinions they did not share. Creating such opportunities for discussion, however, was an effort and, because of this, happened only occasionally.

Learning resources were another problem. Although University libraries made arrangements to supply materials, the wait for delivery was a problem in a half course. Students with university library experience said they missed seeing the book next to the one requested or browsing through the catalogues. Many relied on local libraries and resources in their communities. Generally, local experts who were approached for help were generous with time and expertise. The smaller the student's home community and the more separated from the university, the more often lack of access to learning resources was identified as a problem.

Perceptions of the university's attitude to distance students also influenced students' opinions about the distance learning experience. Support staff had an important effect on students' perceptions. As one student said, "If you can't show you care by smiling, having everything run smoothly is the next best thing." Many students reported that they felt like second class citizens, either because they were post-RNs in a school that emphasized generic nursing education or because they were distance students, especially if they were in the same city. Distance students did not get important notices, did not know about special course offerings, and were criticized for missing information on bulletin boards. If materials did not arrive at distance sites in time for class, or if video transmissions were presented too late to be applied to correspondence assignments, students felt discriminated against. However, when messages got through, when questions were answered promptly, and when the secretarial staff treated them with respect, students expressed more positive feelings about the program and the institution.

All students reported that they had learned in the course. A certain degree of content mastery can be assumed by the fact that all passed the course. Continuing interest in nursing issues was reflected by the number of students who wanted to discuss particular issues during the interviews.

There is no doubt that these students experienced increased self-esteem. They were proud of their success in juggling job, family, and school and of learning things they thought important. One person commented that "You get no feedback at work on when you're doing well. You only hear when there are problems, but in courses, marks let you know how you're doing." The very positive feeling conveyed by most of the students was impressive. Even those with many complaints and concerns about the university, the course, and distance education were pleased with themselves.

Most of the students reported attitude changes. On the whole, these changes reflected the positions desired by professional organizations and educators for baccalaureate nurses. Some reported no change, but their stated opinions about issues like entry to practice, nursing theory, and nursing research reflected those of nursing organizations. Some may have enrolled in the degree program at the outset because they were already socialized to professional attitudes.

As a result of taking the course, several respondents reported that they had become more active in professional organizations, attended more meetings, were involved in things like political action committees, and were paying more attention to the news sections of professional journals. Many also reported feeling more proud of nursing as a profession and their place in it. Some, however, expressed disappointment in nursing and its inability to take its rightful place in the health care system. These comments indicated that the students were thinking a good deal about nursing issues and what the profession meant to them.

As happens in profound change processes, some found the experience of attitude change painful. One student reported that she found herself siding with people she did not want to agree with at work. Another noted that she could sense changes occurring in her, but that they had not yet been realized. A few felt that they had not changed in any significant way. Woolley (1978) points out that students in post-RN programs may choose not to change when faced with new options, but that choice is better than blind acceptance of a set of prescribed behaviours.

The reports provide evidence that the students were becoming resocialized into a new subgroup. It is possible that in the interviews these students provided the answers they thought a member of the nursing education establishment would want to hear. If that were the case, they certainly knew which answers were professionally acceptable. Some of interviewees made jokes about things like nursing theory, which indicated that they were part of an "in group." Some mentioned using a new vocabulary and being accused by other baccalaureate nurses of "talking like our teachers."

One feature of their move to professionalism through distance education was the influence of peers within their communities. In order to share what they were learning, they turned to those who could understand them, who already held degrees, or who were studying. The negative reactions of the old peer group drove them into a new peer group and helped to reinforce new values and attitudes.

The assumption in the literature has been that it is the isolation in the university milieu that promotes the resocialization of post-RN students (Gray, 1980; Lum, 1978). On this basis, it could be predicted that neither group of students would show much attitude change and what change did occur would more likely be evident amongst the teleconference groups. The responses of correspondence students, however, were very similar to those of students enrolled in group-oriented courses. Attitudes, it seems, can be affected by a variety of means, especially when the student is highly motivated.

One negative outcome was the apparent passive acceptance of the program by the students. Despite the stated desire for self-development, students seldom went beyond the required readings and assignments. It appears as if for many of these multiple-role women, the goal was to achieve the degree in the minimum amount of time. Expending energy on self-direction seemingly was not a priority. Some students expressed concern, noted by Rumble (1986), that they were being indoctrinated. Audioteleconferencing, which provides more exposure to a variety of points of view, was preferred by one student for that reason.

This research dealt with only a small sample of Canadian nurses taking courses by distance education. Because of this, the number of commonalities found within and among groups cannot be generalized without caution to other courses or to other universities. It is important to note, too, that only women were interviewed. Although the overwhelming majority of nurses are women, the male perspective must be taken into account at some point. Furthermore, the telephone interview technique can limit the depth of responses received. Without visual cues, it is more difficult to establish trust and for the interviewer to pick up on nuances. Finally, it must be noted that the analysis may reflect researcher biases.

Post-RN nursing students increasingly are learning by distance methods. Teleconferencing has the advantage of allowing group interaction and discussion. It does have limitations, however, including fixed time schedules and, in this instance, the need to travel. Correspondence study allows the student more flexibility in time management and, therefore, is better suited for shift workers and multiple-role women. It is not ideal, however, for group-oriented learners. Regardless of the mode of delivery, the instructor continues to play an important role. Instructors affect in important ways the nature of the experience and what is learned. Interestingly, despite the opportunities teleconferencing provides for students to interact, all respondents reported feelings of isolation and alienation caused by separation from the university and the lack of opportunity for face-to-face classes.

In order to meet the needs of distance nursing students, nursing educators should use a variety of distance teaching methods to allow students the opportunity to choose options that are compatible with their learning styles and their circumstances. Local degree-prepared nurses should be encouraged to foster learning and attitude change among distance students. They can also help to reduce the isolation felt by distance students. Universities must treat their distance students with respect by treating them courteously. We can learn from the experiences of these highly motivated nurses. In so doing, distance educators in nursing will be better able to deal with the less motivated, but still demanding, students we predict will enrol in distance education courses to meet the changing nursing entry to practice requirements.

Bailey, C. (1987a). Nursing distance education in Alberta: A preliminary history, Part 1. AARN Newsletter, 43(1), 13–15.

Bailey, C. (1987b). Nursing distance education in Alberta: A preliminary history, Part 2. AARN Newsletter, 43(2), 15–17.

Barker, B. O., Frisbie, A. G., & Patrick, K. R. (1989). Broadening the definition of distance education in light of the new telecommunications technologies. The American Journal of Distance Education, 3(1), 20–29.

Booth, S., & Brooks, C. (1988). Adult learning strategies: An instructor's toolkit by Ontario adult educators. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Skills Development.

Burge, E., Wilson, J., & Mehler, A. (1984). Communications and information technologies and distance education in Canada. New technologies in Canadian education: Paper 5. Toronto: Ontario Educational Communications Authority.

Calvert, J. (1986). Research in Canadian distance education. In I. Mugridge & D. Kaufman (Eds.), Distance education in Canada (pp. 94–110). London: Croom Helm.

Campariello, J. A. (1988). When professional nurses return to school: A study of role conflict and well- being in multiple role women. Journal of Professional Nursing, 4(2), 136–140.

Carey, R., & Peruniak, G. (1982). Institutional collaboration in extending professional educational opportunities for nurses. Nursing Papers, 14(3), 57–61.

Carver, J., & MacKay, R. C. (1986). Interactive television brings university classes to the home and workplace. Canadian Journal of Educational Communications, 15(1), 19–28.

Cervinskas, J., & Waniewicz, I. (1984). Telehealth: Telecommunications technology in health care and health education in Canada. New technologies in Canadian education: Paper 15. Toronto: TV Ontario, Office of Development Research.

Charbonneau, L. (1982). Telehealth: Making health care truly accessible in the north. Canadian Nurse, 78(9), 18–23.

Collins, F. B. (1982). Televised nursing education in British Columbia. Canadian Nurse, 78(9), 16.

Croft, M. (1987). The post R.N. degree: A proposal for collaborative programme development by Laurentian University of Sudbury and Lakehead University, Thunder Bay. Unpublished proposal, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario.

DuGas, B. W., & Casey, A. M. (1987). Teleconferencing. Canadian Nurse, 83(5), 22–25.

Faith, K. (Ed.). (1989). Toward new horizons for women in distance education: International perspectives. London: Routledge.

Farrell, G. M., & Haughey, M. (1986). The future of open learning. In I. Mugridge & D. Kaufman (Eds.), Distance education in Canada (pp. 30–35). London: Croom Helm.

Forsythe, K. (1983). The human interface: Teachers in the new age. PLET, 20(3), 161–166.

Gray, F. I. (1980). Socialization of the RN in baccalaureate nursing education. In National League for Nursing, Baccalaureate nursing education for registered nurses: Issues and approaches (pp. 11–19) (NLN publication #15–1812). New York: Author.

Holmberg, B. (1983). Section 1: The concept of distance education. In D. Sewart, D. Keegan, & B. Holmberg (Eds.), Distance education: International perspectives (pp. 1–5). London: Croom Helm.

Iman, H. (1987). Review: The invisible tutor: A survey of student views of the tutor in distance education, by Sam M. Rouse. ICDE Bulletin, 14, 67–69.

Lum, J. L. J. (1978). Reference groups and professional socialization. In M. E. Hardy & M. E. Conway, Role theory: Perspectives for health professionals (pp. 137–156). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1984). Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Minnis, J. R. (1984). Supporting paper III: Distance education in Canada: Toward a typology of learning activities for adults. In Ramkhamhaeng University, Proceedings: International conference on open higher education (pp. 178–190). Bangkok, Thailand: Author.

Mugridge, I., & Kaufman, D. (Eds.). (1986). Distance education in Canada. London: Croom Helm.

Rogers, N. S. (1986). Changing attitudes through distance learning. Open Learning, 1(3), 12–17.

Rumble, G. (1986). The planning and management of distance education. London: Croom Helm.

Seagal, S., & Horne, D. (1985). The technology of humanity. Topanga Canyon, CA: Human Dynamics.

Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Woolley, A. S. (1978). From RN to BSN: Faculty perceptions. Nursing Outlook, 26(2), 103–108.

Betty Cragg is an Assistant Professor and Head of the Post-RN Program, School of Nursing, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario. She recently completed her Ed.D. in Adult Education at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, Toronto. Her dissertation was on distance education.