Impact of Adults' Preferred Learning Styles and Perception of Barriers on Completion of External Baccalaureate Degree Programs |

VOL. 7, No. 1, 39-51

Multivariate analyses identified significant differences in both learning styles and perceived barriers of completers and noncompleters. No relation-ship was determined between students' preferred learning styles and perception of barriers to completion of an external baccalaureate degree. Additional multivariate studies focusing on motivation, expectancy, and locus of control seem indicated.

Des analyses multifactorielles ont discerné des différences significatives entre les étudiants sortants et les démissionnaires quant aux styles d'apprentissage et aux entraves perçues. Aucun lien n'a été établi entre les styles d'apprentissage privilégiés par l'étudiant et sa perception d'entraves à l'achèvement d'un programme externe de baccalauréat. Des études multifactorielles supplémentaires axées sur la motivation, l'expectative et le lieu de contrôle semblent indiquées.

Participation and persistence in education and those factors that contribute to their occurrence continue to interest practitioners and researchers alike. As Powell, Conway, and Ross (1990) so aptly note:

The question of why some students successfully study through distance education and others do not is becoming increasingly important as distance education moves from a marginal to an integral role in the provision of post-secondary education. (p. 5)

A number of theoretical models of attrition have emerged to provide explanation and prediction. The one point of agreement is the multivariate nature of the phenomenon of attrition. Variables posited include those related to the individual student, for example, identified as "background" (Billings, 1988) or "predisposing" (Powell, Conway, & Ross, 1990); the student's individual circumstances, for example, "environmental" (Billings, 1988) or "life changes" (Powell et al. 1990); and organizational or institutional (DiSilvestro & Markowitz, 1982; Sweet, 1986). The prime concern, the criterion variable, is the persistence behaviour of the student learning at a distance defined as course completion (e.g., Billings, 1988; Powell et al., 1990) or degree completion (e.g., Langenbach & Korhonen, 1988; Coggins, 1988).

Toward the end of increasing understanding of those variables associated with persistence and non-persistence, this exploratory study investigated the relationships among adult students' preferred learning styles, perception of barriers to completion, and the successful completion of baccalaureate degrees pursued at a distance.

Kurt Lewin (1936) has suggested that a person's behaviour (B) is a function of that person (P) and his or her psychological environment (E) or B=f(P,E). More specifically, field theory suggests that the effect of simultaneous psychological forces operating in the life space of an individual changes that life space and consequently provides the basis for psychological behaviour. Life space encompasses both the individual and his or her psychological environment - that part of a person's physical and social environment with which the person is mentally engaged at the time. Life space, then, includes the changing interrelationships among the person; his or her environment; and perceived needs, goals, and barriers to these goals.

The concepts of vector and valance are also of critical import in under-standing an individual's behaviour. Vector refers to the strength of a force that influences psychological movement either toward or away from a goal with the valence reflecting the direction of that movement: either attraction or repulsion. For example, if obtaining a baccalaureate degree at a distance is a goal of the learner, the force (vector) has a positive valence. If, however, over time the student finds the isolation of studying at a distance intolerable, motivation dwindling, lack of support at home or at work discouraging, and so forth the valence may become negative.

Several educational researchers have built on the work of Lewin, creating theoretical models of participation and persistence which incorporate many of his key concepts. One such model is the Boshier Congruence Model of Educational Participation and Dropout (Boshier, 1973). Boshier posits that both participation and dropout stem from an interaction of both internal psychological variables (either growth- motivated or deficiencymotivated) and external environmental variables. He suggests that a growth- motivated person is inner directed, autonomous, open to new experiences, can be spontaneous and creative, and is active in creating the future. Deficiency-motivated people are often directed by social and environmental pressures. They are more afraid of the environment and often determine their future by being more reactive to the environment. Boshier believes that enrolling for deficiency reasons is associated with intra-self incongruence, self/other incongruence, and unhappiness with the educational environment. Therefore, participation and dropout can be viewed as a function of the magnitude of the discrepancy among/between the participant's self-concept, a match between student and other students, instructor, educational processes, and the environment, including job responsibilities, home responsibilities, and so forth. Social, psychological, and environmental variables are posited as mediating the participation/dropout behaviour with Boshier's past research suggesting that dropout is associated with a student's feelings of incongruence but that this incongruence is projected onto the educational environment.

Building on Lewin and Boshier, Cross (1981) has developed a Chain of Response model that focuses on barriers to participation. In earlier research focusing on adult students' participation in traditional educational programs, Cross identified three categories of barriers to participation: situational, institutional, and dispositional. Although these barriers are often considered as crucial to the decision to participate or not to participate in educational programs, they continue to loom as important as students reconsider their participation at certain times during their studies.

Definitionally, situational barriers refer to those impediments that arise from the adult's particular circumstances in life at the time, for example, the need to spend time with family members. Difficulties with the scheduling of classes or the registration process represent examples of institutional barriers as defined by Cross (1981). Dispositional barriers refer to the student's concept of self as a learner. Low self- concept is one example of a dispositional barrier that may hamper participation and learning.

In addition to those barriers identified by Cross (1981) in her research, the authors suggest that the independent study method itself presents a barrier to some learners because of its relative isolation and the physical distance between learner and instructor and learner and classmates.

Individuals, of course, do experience and perceive barriers differently. One characteristic that may account for differences in perception is students' learning styles: their unique and consistent approaches to learning. Given that certain learning styles seem more suitable for the particular demands of distance learning, although the research is by no means conclusive, it follows that where students' preferred learning styles are well matched with the demands of independent study, students are likely to view the barriers to completion less intensely. Further, students are more likely to complete an external baccalaureate degree program when compared to students whose learning styles are not well matched to the unique characteristics of independent learning.

Utilizing the Boshier (1973) congruence model of educational participation and dropout as a theoretical framework, this study focused on the self/ student and self/lecturer congruence in terms of learning style preferences, especially conditions and modes of learning. In addition, sub-environmental variables, for example, situational and institutional barriers, and selected mediating psychosocial variables such as expectancy were explored. Specifically, the research addressed the question: Are there particular learning styles, psychosocial, and sub-environmental variables that are predictors of a greater potential to succeed in external baccalaureate degree programs? The hypotheses that directed the analyses stated:

A further research objective was to discover, through discriminant analyses, those variables that appear to provide some degree of predictability relative to the phenomenon of persistence in distance education.

In this post hoc study, data were collected from a stratified random sample of students previously associated with the four University of Wisconsin System Extended Degree programs. The random sample was stratified on the basis of both program (representatives from each of four Extended Degree programs) and completion status (representatives from the categories of completers and non-completers) with an emphasis on equal cells. A total sample of 210 was drawn from lists of program graduates from June 30, 1983 through July 1, 1986 and the enrollees from the period January 1, 1983 through December 30, 1985 who had dropped out prior to completion. Altogether 164 returned the appropriate questionnaires, yielding a response rate of 78.1%. Eleven sets of materials from noncompleters were unusable, yielding an overall response rate of 72.9%. A short survey instrument was used to collect selected demographic data. A "barriers" instrument was developed specifically for this study to provide an assessment of students' perceived barriers to completion of their external degree programs. The instrument was an adaptation of a "barriers instrument" developed by Schmidt (1983) for use with returning adult students in a traditional baccalaureate program. Based on categories suggested by the research of Cross (1981) with the addition of a fourth category of barriers labelled "independent study barriers" designed for the purpose of this study, the instrument consisted of 36 items and one open- ended question requesting information on any other factor(s) that had an impact on their life as an external degree student. The instrument used a Likert scale to indicate the amount of difficulty students experienced in dealing with each of the situational, dispositional, institutional, and independent study barriers. Using Cronbach's alpha, the reliability score for the overall scale was

.89 with subscale reliabilities as follows: situation barriers, .80; independent study barriers, .80; dispositional barriers, .74; and institutional barriers, .55. Learning style was measured by the Canfield Learning Style Inventory (CLSI, 1980). The CLSI is a 30 item assessment using a 4-point rank order procedure for each item. The instrument generates a total of 21 subscale variables grouped into four major areas: preferred conditions, content, modes, and expectancy (performance). Conditions variables include a preference for the following: peer affiliation and instructor affiliation, organization and detailed structure, independence and setting one's own goals, and authority and competition. Content variables include preferences for numerics, language (writing and discussion), objects (working with things versus people), and people (interviewing and counselling). Mode variables are comprised of preferences for listening, reading, iconics (audiovisuals), and direct, hands-on experience. The remaining five variables are additive and generate a single expected performance (class grade) score or can be used singly. Subscale reliabilities range from r=.52–.99 and face validity of the instrument has been determined using over 3,000 adult subjects.

As reported earlier (see Coggins, 1988), approximately 60% of the respondents were female with a majority (80.3%) of individuals between the ages of 25 and 45 at the time of enrolment. Seventy-seven percent lived over 51 miles from campus with the majority (36.0%) living from 101–200 miles away. Ninety-three percent of respondents were employed outside of the home with 75.8% of these individuals employed full time during their studies. Approximately 75% were married, 71.2% with children. Chi square analyses showed no significant differences between completers and noncompleters on these variables. Significant differences were found between completers and noncompleters on several other variables, including: intention to complete a degree, levels of education at the time of enrolment, years of college prior to enrolment, and years since last college credit course. Overall, completers expressed an intention to complete a degree, had 2–3 years of college experience, and had taken a college credit course within the two years prior to enrolment in an external degree program.

In comparing completers and noncompleters on the overall intensity with which they perceive barriers to completion in their program of study, completers were significantly different from noncompleters in their perceptions (t=5.54, df=151, p=.0000). On further analysis it was determined that institutional barriers were perceived with similar intensity by completers and noncompleters (t=-.70, df=151, p=.4828). However, significant differences were found between the perceptions of completers and noncompleters when situation barriers (t=-4.27, df=151, p=.0000), independent study barriers (t=-4.87, df=151, p=.0000), and dispositional barriers (t=-5.89, df=151, p=.0000) were compared.

Looking within each of the barrier categories for further insights, yet recognizing that conducting a large number of t-tests may yield significance where none actually exists, the situational barriers that noncompleters perceived as having caused significantly more problems included: finding enough time to study, balancing home responsibilities with studies, and balancing job responsibilities with studies. Completers and noncompleters differed significantly on their perception of independent study barriers including: having few opportunities to meet face-to-face with instructors, deciding how to study, having few opportunities for discussion, the time required to complete a degree, feeling isolated, receiving sufficient guidance from the instructor, and taking responsibility for their own studies. Motivation, energy, confidence in their ability, increased stress, ability to concentrate, thinking they were too old to be students, not knowing the value of their degree, and setting specific study times were all dispositional barriers that noncompleters felt significantly more intensely than completers. Interestingly enough, both groups perceived test anxiety similarly.

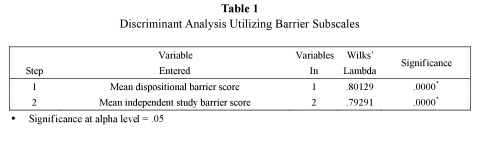

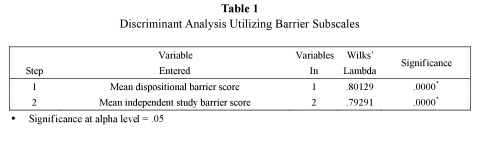

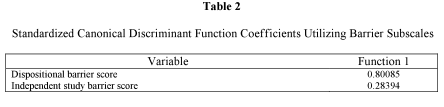

On further analysis, stepwise discriminant analysis revealed that the independent study and dispositional barrier categories were the most relevant to prediction.

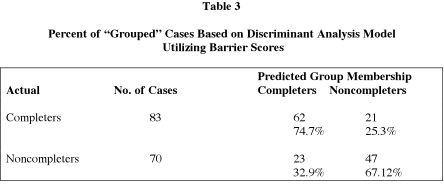

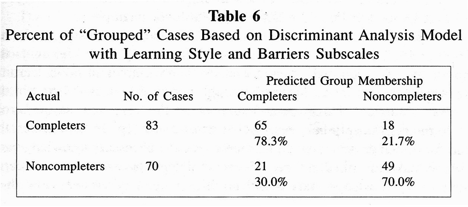

The percent of "grouped" cases correctly classified based on the model generated using only barrier scores was 71.24%. It should be noted, however, that the percentage of grouped cases classified correctly, for example, in and , is well known to be biased upward unless applied to a randomly selected holdout sample. Further, the percentage should also be compared to the chance criterion, which for this study is 50.36%.

Hotelling's T statistic was used to determine if learning style differences existed between completers and noncompleters. Again, as reported earlier, this multivariate test of significance (S=1, m=9 1¦2, N=64 1¦2) was significant with F=.028. Further univariate analyses isolated those learning style subscales that account for the differences between completers and noncompleters - Expectancy of an A (F=.000), Expectancy of a C (F=.000), Overall expectancy (F=.043), Inanimate objects (F=.026), and People (F=.043). On closer examination of the latter two subscales, it was noted that when comparing respondents by program, the Chi square analysis revealed significant differences in cell sizes at .05 level (Chi square=16.74, df=3, p=.0008), with one of the four external degree programs providing a limited number of completers in comparison to the other programs. Post hoc Scheffe's also identified differences among and between programs in terms of learners' content preferences.

A discriminant analysis was conducted to determine the best linear combination for distinguishing among completers and noncompleters on the basis of learning style data. Seven variables made up the final model including in order of addition: C–Expectancy, People–Content, Numeric– Content, Peers–Conditions, D–Expectancy, Direct Experience–Mode, and Details–Conditions. Canonical discriminant functions yielded an eigenvalue of 0.21594, a canonical correlation of 0.4214, Wilks' Lambda 0.8224, Chi squared=28.839, df=7, p=.0002. The percent of "grouped" cases correctly classified based on the model generated by the discriminant analysis was

69.93%, with 79.5% of completers and 58.6% noncompleters correctly classified (again recall the concern relative to upward biases). It should be noted that Overall Expectancy of Success alone resulted in correct classification of 68.7% of completers and 60% of noncompleters for an overall rate of 64.71%. (For further discussion see Coggins, 1988.) In further analysis, multiple regression procedures determined that only small amounts of variance in barriers could be explained by the learning style subscales. More specifically, reading accounted for 12% of the variance, expectancy and goal setting explained an additional 6% and 4% respectively.

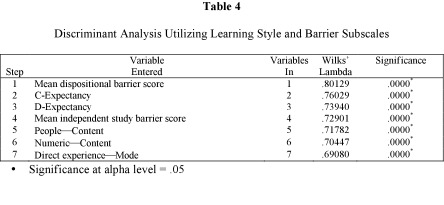

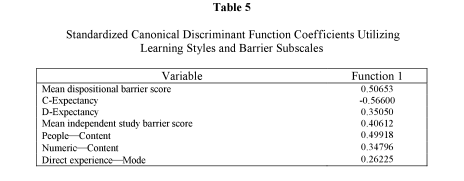

Lastly, a stepwise discriminant analysis incorporating both learning style variables and barrier categories was conducted using Wilks' Lambda as the criterion. The results of these analyses are shown in Table 4.

Canonical discriminant fuctions yielded an eigenvalue of 0.26117, a canonical correlation of 0.45507, Wilks' Lambda 0.79291, Chi squared=34.806, .=.0000.

Overall, both perception of barriers and learning style data differentiated completers from non- completers with only a small amount of the variance in barriers explained by learning styles. On closer examination, however, several psychological variables appeared to account for these differences between completers and non-completers. One key variable appears to be related to the confidence of the student studying at a distance. Expectations of receiving a C or a D suggest a lack of self-confidence, based perhaps on an assessment of personal competence. Further, those subcategories in the category of dispositional barriers that appear to be the best predictors of completion in this study included: confidence in ability, perception of being too old to learn, and ability to concentrate. These findings parallel several of the key variables isolated by Langenbach and Korhonen (1988) and Coldeway, MacRury, and Spencer (1980) in their earlier research.

In addition to confidence and competence, commitment may also play a significant part in noncompletion as the data suggests that motivation, knowing the value of the degree, and time required to complete a degree are barriers that differ significantly between completers and noncompleters.

Also of interest is the difference (in the predicted direction, but not significant) in the need for peer affiliation and detailed structure (conditions of learning) noted in the assessment of learning styles. Similar significant differences between completers and noncompleters are noted in the following subcategories of the independent study barriers category: having few opportunities for discussion; feeling isolated; having few opportunities to meet face-to-face with instructor; deciding how to study; receiving sufficient guidance from the instructor; and taking responsibility for one's own studies, closely paralleling earlier findings of Childs (1971), Billingham and Travaglini (1981), and Coldeway (1986), for example.

Recent writings of Pratt (1988) may provide some insights. In his article entitled "Andragogy as a relational construct," Pratt highlights the importance of situational, learner, and teacher variables in adult learning (traditional face-to-face learning, although not specified, is inferred in the article). He notes, "Direction and support are the keys to a teacher's role and to the relationship between teacher and learner" (p. 165). Further, the need for direction occurs when learners "lack the necessary knowledge and skills to make informed choices." Noncompleters appear to voice concerns about their knowledge, skills, and abilities in general as we view their perceptions of dispositional barriers. In addition, expectancy scores suggest a lack of confidence in their ability to accomplish their degree goal.

Further, many noncompleters also indicated they had no intention of completing a degree. Whether self-deception, rationalization, or fact, this lack of commitment simply enhances the need for direction and support from the teacher. As Billings (1988) notes, "intentions have been demonstrated to be the consistently best predictors of dropout in attrition studies...and in progress toward completion of correspondence courses." (p.30)

Our data would suggest a strong need for direction and support, particularly during the student's early stages of involvement in an external degree program and especially during the initial coursework. More specifically, an opportunity for self-assessment in terms of previously gained competencies should be provided. Past research has shown adults frequently underestimate their abilities in reading, writing, and mathematics, however less so for the latter (Michler, 1982). Additionally, study skills coursework to strengthen both confidence and competence to successfully engage in distance learning seem indicated. Adults need to learn strategies that fit their unique life styles and learning styles and that they can apply to provide structure and direction to their studies.

Programs should also consider the addition of preadmission counselling focusing on a match between interests and intentions of student and the degree program. Data noted briefly above suggests that where content interests, as indicated in learning preferences, do not match those of the educational program, dropout will increase. Finding that match between interests and degree emphasis seems all important. Further commitment to completion of a degree program should be assessed. Where external motivation seems to predominate, the dropout potential seems great without careful and continual support and direction.

Data from previous studies suggest that students who have had a successful experience with other distance education courses (correspondence courses in this case) are most likely to complete a course (Coldeway, 1982). Thus it seems that early intervention is critical. Providing assistance with pacing, timelines, detail, interface with other students taking the same course or with peer tutors, and incorporation of optional face-to-face or mediated distance meetings with the instructor represent just a few ways early direction and support could be provided. One might hypothesize that these types of direction and support could be gradually diminished without a parallel diminishing of student success in later coursework.

Given the increasing emphasis on learning at a distance and the limited knowledge of persistence in credit and non-credit learning, additional re-search seems indicated. The findings of this study suggest motivation, locus of control, self-regulation, and expectancy of success, as well as teacher direction and support would appear to be areas of needed research. Further, interviews with completers and non- completers suggest learning style differences not isolated with the instrumentation employed in this study. Assessment techniques continue to require attention.

As suggested by many in the field, multivariate studies with a sound theoretical framework can add much to our body of understanding.

1. Based on a research project partially funded by the Spencer Foundation.

Billingham, C., & Travaglini, B. (1981). Predicting adult academic success in an undergraduate program. Alternative Higher Education, 5, 169–182

Billings, D. M. (1988). A conceptual model of correspondence course completion. The American Journal of Distance Education, 2(2), 23–35.

Boshier, R. (1973). Educational participation and dropout: A theoretical model. Adult Education, 23, 255–282.

Canfield, A. (1980). Learning styles inventory manual. Ann Arbor, MI: Humanics.

Childs, G. (1971). Recent research developments in correspondence education. In O. MacKenzie & E. Christensen (Eds.), The changing world of correspondence study (pp. 229–249). University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Coggins, C. (1988). Preferred learning styles and their impact on completion of external degree programs. The American Journal of Distance Education, 2(1), 25–32.

Coldeway, D. O. (1982). A review of recent research on distance learning. In J. S. Daniel, M. A. Stroud, and J. R. Thompson (Eds.), Learning at a distance: A world perspective. Athabasca University/International Council for Correspondence Education.

Coldeway, D. O. (1986). Learner characteristics and success. In I. Mugridge & D. Kaufman (Eds.), Distance education in Canada (pp. 81–93). London: Croom Helm.

Coldeway, D. O., MacRury, K., & Spencer, R. E. (1980). Distance education from aearner's perspective: The results of individual tracking at Athabasca University (REDEAL Research Report #10, Project REDEAL). Athabasca, Alta: Athabasca University.

Cross, K. P. (1981). Adults as learners. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. DiSilvestro, F., & Markowitz, H. (1982). Contracts and completion rates in correspondence study. Journal of Educational Research, 75(4), 218– 221.

Langenbach, M., & Korhonen, L. (1988). Persisters and nonpersisters in a graduate level, nontraditional, liberal education program. Adult Education Quarterly, 38(3), 136–148.

Lewin, K. (1936). Principles of topological psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Michler, C. (1982). A follow-up study of adult graduates of the University of Wisconsin system. Green Bay, WI: University of Wisconsin, Wisconsin Assessment Center.

Powell, R., Conway, C., & Ross, L. (1990). Effects of student predisposing characteristics on student success. Journal of Distance Education, V(I), 5–19.

Pratt, D. (1988). Andragogy as a relational construct. Adult Education Quarterly, 38, 149–172.

Schmidt, S. (1983). Understanding the culture of adults returning to higher education: Barriers to learning and preferred learning styles. Washington, D.C.: Department of Agriculture. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 242–248)

Sweet, R. (1986). Student dropout in distance education: An application of Tinto's model. Distance Education, 7(2), 201–213.

Chère Campbell Gibson is a faculty member in the Department of Continuing and Vocational Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and past Director of the University of Wisconsin System Extended Degree Programs. Dr. Gibson teaches undergraduate and graduate courses related to learning at a distance. Her research focuses on the learner at a distance with a specific emphasis on persistence and the learner support that might facilitate learning and successful completion.

Arlys Graff is the Director of Community Education for Le Sueur Public Schools in Le Sueur, Minnesota. She holds a Ph.D. from the Department of Continuing and Vocational Education from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.