Faculty Support for University Distance Education |

The study addresses the controversy among academics in conventional universities regarding the credibility of courses offered via distance education. The intent of this research is to explain why some faculty support distance education whereas others do not.

An interpretive perspective and qualitative methods dominated the two-phase study. A mailed survey (n=487) investigated the extent of faculty familiarity with and support for distance education. On the basis of this information, faculty were divided into three categories of support for distance education: supportive, divided support, and opposed. Representatives from each group were then interviewed (n=50). The interviews explored: the degree of congruence between faculty members' perceptions of distance education and their beliefs and values about the accessibility and quality of university education; and the extent to which faculty members considered it feasible to implement distance education successfully.

In general, faculty were not very familiar with or supportive of distance education, except for undergraduate courses. Faculty supported distance education if they considered it to be congruent with their beliefs and values about university education in general. Implications for the planning and development of distance education are discussed.

Cette recherche se penche sur la crédibilité des cours offerts à distance, qui prête à controverse parmi le corps professoral des universités traditionnelles. L'étude cherche à expliquer pourquoi certains professeurs favorisent l'éducation à distance et d'autres pas.

Cette étude à deux phases a privilégié les méthodes qualitatives et une approche interprétative. Les renseignements obtenus grâce à un sondage postal (n=487) visant à mesurer le degré de familiarité et d'adhésion des professeurs à l'éducation à distance ont permis de distinguer trois degrés d'adhésion : appui, appui mitigé, opposition. Des professeurs de chacune de ces catégories ont ensuite été interviewés (n=50), afin d'identifier d'une part le niveau de cohérence entre les perceptions de l'éducation à distance chez les professeurs et leurs convictions quant à l'accessibilité et la qualité de l'éducation universitaire, et d'autre part à quel point ils croyaient réalisable une mise en application réussie de l'éducation à distance.

Règle générale, les professeurs ne manifestaient ni une large connaissance ni un appui notoire à l'éducation à distance, exception faite des cours de premier cycle. Ils y adhéraient dans la mesure où ils y percevaient un reflet de leurs convictions quant à l'éducation de niveau universitaire en général. Le présent texte explore aussi les leçons à tirer pour la planification et le développement de l'éducation à distance.

One of the major challenges facing the development and expansion of university distance is faculty scepticism about its suitability for university degree credit. Distance education is defined here as an educational method in which the teacher and learners are separated in time and space for the majority, if not all, of the teaching-learning process; two-way communication occurs primarily via print, postal service, and telecommunications (Keegan, 1990).

Distance education may be viewed as a manifestation of the overall expansion, democratization, and diversification of higher education accompanying what Trow (1973, 1987) conceptualized as the transition from an elite to a mass system of higher education. The growth of university distance education world wide has paralleled this change. Societal demands for increased access to higher education continue. The demands are based on utilitarian needs in a rapidly changing society as well as on democratic ideals and on a philosophy of lifelong learning. University distance education is one response to these demands, especially those for more flexible learning opportunities for adults who wish to study part time while fulfilling work and family responsibilities.

The Commission of Inquiry on Canadian University Education concluded that "distance education efforts are excellent and need to be expanded" (Smith, 1991, p. 86). However, the long standing controversy among academics about the credibility of distance education creates implementation problems for planners and difficulties for students in obtaining full recognition for distance courses they have completed. "On one hand the traditionalists often view distance education as the ultimate erosion of academic standards, whereas on the other hand distance education advocates see opposition to their cause as obstructionism and academic protectionism" (Kirby, 1988, p. 115). Students complain "about the problem of credit transfer and about the relative lack of graduate-level courses" in distance education (Smith, 1991, p. 85).

Distance education is often viewed as second-best to classroom, face-to- face instruction (Calvert, 1986; Perry, 1984; Kirby, 1988). This position appears even more prevalent regarding moves to deliver graduate university courses at a distance as "there is a strongly held belief, certainly on the part of some Canadian academics, that there are intrinsic qualities about graduate education that militate against its delivery at a distance" (Kirby, 1988, p. 115). Although distance educators frequently comment on their struggles with the scepticism of university faculty about distance education, there is little systematic exploration of the issue; an issue that is difficult to face constructively but one that will not go away (Kirby, 1988). The purpose of the study reported here was to understand and explain why some faculty support distance education for degree credit while others do not.

The "enigma of academic acceptance" was evident well before the expansion of distance and higher education (MacKenzie & Christenson, 1971). One of the best examples of the controversy was provided by two articles that debated the "stepchild" image of home study, an earlier term for what is now called distance education (Allen, 1960; Stein, 1961). Allen charged that the stepchild treatment of home study was due to ignorance, narrow-mindedness, and snobbery on the part of academics who believed that on-campus study was the only real way to learn. Although Stein (1961) acknowledged "much truth in Allen's excellent analysis," he blamed the faculty involved for part of the difficulty. Stein (1961) claimed that distance educators must be more active professionally, conduct more research, and insist on high standards to overcome prejudice and misinformation.

Wedemeyer (1981) used the notion of "backdoor learning" to depict what he considered the discrimination against independent and other forms of non-traditional university study: "People of quality use the front door; lesser folk carry out their tasks at the back door" (p. xxii). Wedemeyer had been involved in distance education since the 1930s and believed that academic scepticism was due to elitism and unscientific reasoning. Furthermore, he observed that this opposition resulted in restrictive rules and regulations for distance education courses that tended to prohibit credit or other recognition for them. Distance students have complained about problems with transfer credit in Canada (Smith, 1991). In a survey of Canadian universities and colleges, Kirby (1988) found that several universities would not give comparable recognition to a graduate degree completed solely by distance education and would restrict the number of distance courses permitted in a graduate program.

Several studies of faculty attitudes towards university expansion and distance education as well as the literature on universities as organizations and change provided a basis for this study. British studies of faculty attitudes towards university expansion concluded that faculty were concerned about maintaining the elite status of universities and were resistant to change (Ballis Lal, 1972; Halsey & Trow, 1971). Two Australian studies (Adamson, 1976; Anwyl & Bowden, 1986) concluded that attitudes towards distance education reflect basic conceptions about the nature and function of the university.

Studies of faculty involved in distance teaching reported positive faculty attitudes towards distance education despite common concerns about a heavy workload, inadequate rewards, and the major adjustments in teaching required (Burnham, 1988; Clark, Soliman, & Sungalia, 1984; McQuire, 1988; Parer, Croker, & Shaw, 1988; Siaciwena, 1989; Scriven, 1986; Taylor & White, 1991; Willen, 1981). These studies and others (Johnson, 1984; Rishante, 1985; Stinehart, 1987) indicated that faculty familiarity with distance education was consistently associated with more positive views. Few definitive patterns were reported regarding the influence of professional characteristics, although differences by discipline and gender seemed the most important (Johnson, 1978; Schalk, 1984). Research based on the change literature suggested that two categories of the attributes of a change, compatibility and feasibility, had potential for explaining faculty reactions to distance education (Johnson, 1978, 1984).

Little comparative work has been done on differences in the perceptions of faculty who are supportive of, opposed to, or undecided about distance education. The only related Canadian studies on the topic are McQuire's (1985) research on faculty adjustments to working in a distance teaching university, plus Kirby and Garrison's (1990) study of the differences between the perceptions of six graduate deans and six distance education administrators.

The scope of the study was restricted to faculty perceptions of distance education courses for degree credit and to full-time teaching faculty in one conventional Canadian university, The University of British Columbia. How faculty view distance education is important because they make the academic decisions regarding program approval, resource allocation, and regulations governing the recognition of distance education courses for credit towards a degree. One of the distinctive features of universities as organizations is that academic decisions are made by the faculty in committees at the departmental, faculty, and senate levels of university governance (Becher & Kogan, 1980; Clark, 1983; Ross, 1976; Leslie, 1980). The university senate of faculty has ultimate authority over all academic decisions. In senate, faculty from all disciplinary groupings within the university become involved in decisions about any academic program. Hence, faculty who may have little knowledge about a proposal, such as one for distance education, are called upon to make decisions about it (Lindquist, 1974).

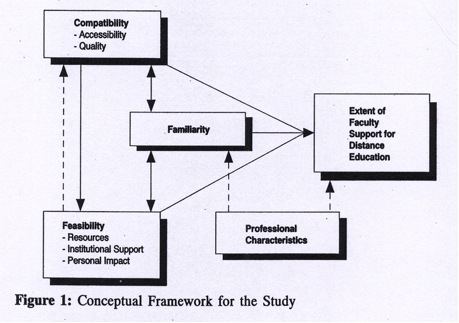

The conceptual framework designed for the study consisted of five concepts (see Figure 1):

As noted earlier, support was defined as how faculty would likely speak about and vote on proposals to offer distance education for degree credit. Familiarity was the extent to which faculty had personal knowledge of distance education from readings, discussions, or involvement in distance education. The professional characteristics investigated were discipline, gender, preference for teaching or research, and research type. Compatibility was defined as the perceived congruence of distance education with the beliefs and values of the individual about the accessibility and quality of university education. Feasibility was the perceived ability to successfully implement distance education in terms of resources, institutional support, and the personal impact of distance teaching on faculty.

The study was conducted in two phases. First, a mailed survey addressed four research questions:

The survey used a Likert-type questionnaire designed and pre-tested for the study. A short explanatory note describing what was meant by distance education was included. The survey sample was selected to allow for subgroup analysis by gender and by four disciplinary groupings used in research on academic culture:

The hard/soft dimension refers to the degree to which a clearly delineated research paradigm exists and the pure/applied dimension refers to the extent of concern with the practical application of subject matter (Becher, 1989; Biglan, 1973).

The second phase of the study used the survey findings to select faculty (n=50) for semi- structured, face-to-face interviews to answer two research questions:

Each one hour interview began with a review of the subjects' responses on the survey questionnaire and proceeded with a set of 18 interview questions about the indicators of compatibility and feasibility identified in the conceptual framework. The interview data were systematically recorded on audiotape for transcription. As the first step in data reduction, a summary of interview data was returned to each subject for verification that the data to be used accurately represented the views expressed. The summary data were then analyzed for major themes and patterns according to the conventions of qualitative research (Guba & Lincoln, 1989; Miles & Huberman, 1984; Strauss, 1987).

An interpretive perspective and qualitative methods dominated the study. It assumed that people behave on the basis of how they interpret situations and that individuals are the acting units in society (Blumer, 1969). The research also assumed that considerable faculty autonomy and self-governance are academic norms (Becher & Kogan, 1980; Clark, 1987). Furthermore, it assumed that distance education is a viable educational delivery method and that faculty are aware of and will honestly report their views about distance education.

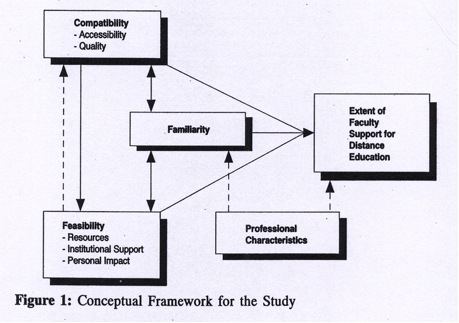

The return rate for the net survey sample of 670 was 73% with responses from 200 women and 287 men as noted in . The survey yielded nominal data that were analysed by descriptive and chi- square statistics with the level of significance set at 0.01.

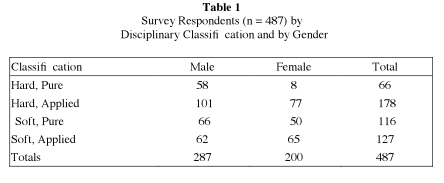

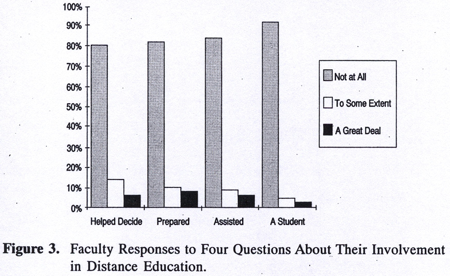

Ten questions on awareness of and involvement with distance education were designed to measure faculty familiarity. Each item had three response categories: 1 = not at all; 2 = to some extent; 3 = a great deal. The majority of respondents were not familiar with distance education beyond hearing and reading about it incidentally, as displayed in . Seventy percent (70%) of subjects had heard about distance education offered by UBC. More respondents (79%) had heard about distance education offered by other universities and colleges. Fifty-five percent (55%) had read about distance education generally in newspapers or magazines. Sixteen percent (16%) of respondents had read about distance education in scholarly journals. One third (33%) had discussed with other faculty UBC's role in providing distance education courses for degree credit and fewer (22%) had debated with other faculty controversial issues regarding distance education.

Few faculty had knowledge of distance education from any type of personal involvement with it, as noted in . Twenty percent (20%) had been personally involved in faculty committee decisions about distance education course offerings. Eighteen percent (18%) had prepared distance teaching materials and 15% had been involved in distance teaching by assisting, advising, or tutoring distance students. Six percent (6%) had been distance students themselves. This overall lack of faculty familiarity with distance education is similar to that reported by other studies (Johnson, 1978; Kirby & Garrison, 1990; Rishante, 1985).

The familiarity scores were grouped into three categories for analysis purposes:

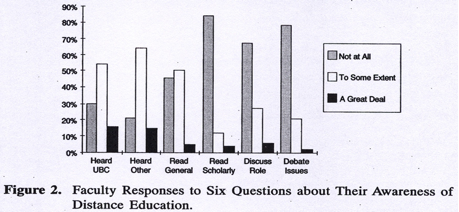

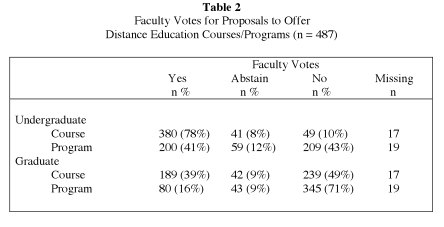

One questionnaire item asked subjects how they would likely speak in faculty meetings about distance education courses for degree credit and the majority (54%) responded positively. Four subsequent questions asked how they would likely vote on distance education proposals in a faculty meeting. Just over three quarters (78%) of the respondents would likely vote in favour of a distance course for undergraduate degree credit, but this was the only proposal that the majority would support (see ). About 40% would likely vote for an undergraduate program or for a graduate course at a distance and very few (16%) would likely vote for graduate programs to be offered this way. This indicated that faculty tended to be reserved and conditional about voting in favour of distance education proposals. The majority would likely speak positively about distance education in principle and vote favourably on a proposal to offer an undergraduate distance education course, but they would not be in favour of more extensive endeavours.

Because faculty were not very familiar with the topic, it is notable that few faculty (8–12%) indicated that they would abstain from voting. This supports the assumption that faculty have definite opinions about distance education even when they do not know much about it and that these opinions will likely be reflected in how they vote in faculty committee meetings for distance education proposals. Faculty with high familiarity with distance education would speak more positively about and vote more favourably on distance education than those with low or some familiarity.

Faculty in the hard and pure disciplines were significantly less supportive of distance education than those in the soft and applied disciplines. The hard, pure natural science grouping was the least supportive overall. This finding concurs with that of Thompson and Brewster (1978) who studied faculty voting patterns in senate. They found that the hard, science disciplines voted more unfavourably than others on curriculum changes that gave students more course choices.

There were significant differences in faculty support for distance education by gender with more women than men voting in favour of distance education at the graduate level. However, there were few women (n=8) in the hard, pure disciplinary grouping that gave the least support to distance education. There was no significant difference in faculty support for distance education according to their interests in teaching or research, although those who were more interested in teaching, or in both teaching and research equally rather than research, tended to be both more familiar with and more supportive of distance education.

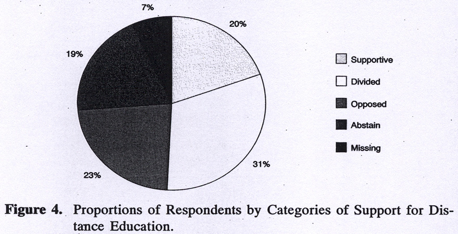

On the basis of response patterns to the four voting questions, seventy-three percent (73%; n=356) of the respondents were grouped into three categories of support for distance education:

A total of 50 faculty were interviewed representing the three categories of support for distance education identified by the survey (supportive=14; divided support=22; opposed=14). The subjects interviewed had about the same variation in familiarity with distance education as the survey respondents. There were about equal numbers (n=11 to 14) interviewed from each of the four disciplinary groupings and there were 21 women and 29 men.

The interviews revealed that faculty support for distance education was largely determined by the perceived compatibility of distance education with their beliefs and values about university education in general. Feasibility was of relatively little concern for any group and most comments about feasibility were related to beliefs about education. For example, one subject remarked:

I think that anything which is right on the basis of an idea, can be worked out in terms of money. If it is a worthwhile idea there is a way of realizing it. So the important thing is to decide whether the idea is worthwhile and then resources can be found.

Lack of familiarity with distance education may account for some of this absence of concern for feasibility, but the subjects who were highly familiar with distance education did not talk as much about feasibility as compatibility issues. Additionally, faculty in the supportive group with low familiarity with distance education supported it because they believed that university education should be more accessible to people.

Data analysis for the three groups of subjects interviewed showed differences in several areas:

the emphasis given to accessibility and quality issues views about instruction and the use of technology for interaction purposes and need for student experience on a university campus.

A comparative analysis of these differences used the notion of elite versus mass higher education to draw conclusions about the reasons why some faculty support distance education while others do not (Trow, 1973; 1987). Elite higher education is marked by high selectivity, a close student-teacher relationship, and intense, structured study of arts and science subjects associated with a liberal education. It is concerned with shaping the mind and character of students in order to prepare them for elite roles in government and the learned professions. In contrast, mass higher education is marked by its more open access to a wider range of students, including older, part-time students (Trow, 1987). It uses a more flexible, modular form of instruction and emphasizes the preparation of the population for employment and for adapting to a rapidly changing and highly technological society.

The analysis of interview data concluded that faculty who were supportive of distance education held the beliefs and values Trow (1973) associated with mass education while those who were opposed tended to believe in an elite approach to university education. There was a substantial divided group who were in a conflict about the priority that should be given to the major values involved, the accessibility and quality of university education.

The relative emphasis faculty in the different groups of support for distance education placed on accessibility and quality issues illustrates the different values, conflicts, and compromises associated with a mass versus an elite conception of university education. A mass system of higher education places value on more open access to larger numbers of the population. It is believed that this conflicts with the values of an elite system that is more selective and focuses on preparing a smaller number of individuals with the highest of academic standards. The central dilemma is that "more means worse" (Trow, 1987, p. 274).

Most faculty who supported distance education emphasized accessibility values, while those who opposed distance education viewed quality as the priority (). For example, a supportive subject stated that

If you said, what is the basis of my whole positive view towards distance education, it is to make it more equitable, so that other people would have access to a university education. We're taking money now in taxes from the working class to educate the middle class and we can't go on that way. . . . I'm all for change. I do think we have to work towards some equitable order where there's fairness and people have a good chance of achieving what they wish.

In contrast, subjects who were opposed to distance education made statements like the following:

I think it's important to get good quality people into the system, then when they go out you really have superior people, to compete as world class scientists, or in whatever profession. . . . I guess maybe I can be faulted in thinking that the university should be an elite place. I think it should be an elite place . . . we put our best people there so that the next generation of people that [sic] come out will even be better.

Faculty who were divided in their support for distance education tried to balance values about both accessibility and quality and many expressed a value conflict that called for a compromise of their ideal notions about quality to avoid denying educational opportunities to people. This conflict was indicated by comments such as the following:

I don't think it's as good an education as you get on campus. On the other hand, you're giving much more accessibility and so you've got this trade off. . . . I think it's a good trade off for at least part of the way . . . and there are things you can do to increase accessibility while giving as good an experience, an educational experience as possible.

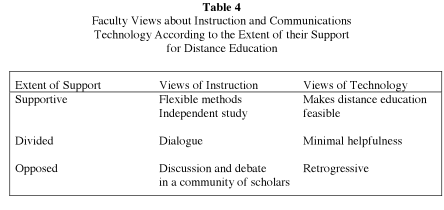

Faculty in the different groups of support for distance education also had different understandings about what constituted acceptable instruction and about the use of communications technology (). Trow (1973) claimed that in an elite system instruction tends to be more structured and marked by seminars with a personal relationship between student and teacher. A mass approach, on the other hand, relies on alternate forms of instruction that are flexible, modular, and include the use of technological aids.

Faculty who supported distance education believed in flexible forms of instruction and independent study because they claimed that "Different teaching methods rarely show significantly different results." Faculty who were divided in their support for distance education preferred to see more structure with more face-to-face contact for dialogue and debate within a learning group. They believed that the learning process in a group was quite different and more effective than isolated, private study. The opposed group held ideals of instruction that dictated face-to-face interaction within a university community of scholars, as indicated by the following comment:

The essence for me of undergraduate education is almost a one on one contact between an intelligent student and a quite intelligent faculty member, and as you deviate from that, I think, the system becomes less and less satisfactory. . . . Education to me is, in this ideal world of one on one, intellectual confrontation, which I don't think you can do or at least get very much of at a distance.

The faculty who supported distance education were very positive about the use of technology and saw it as making the implementation of distance education practical. To them, learning with the use of technology was just another educational method that could be just as effective as regular instruction.

The problem of designing an interactive learning process in distance education is a technical one. Fax machines and computer conferencing could be used for graduate seminars. It would be a different kind of seminar, occurring over a different time period, but it would be suitable. So electronic mail, with fax for hard copies, I think that's probably why I was so positive about it [distance education].

Faculty in the divided support group believed technology could have some minimal utility but that some personal interaction with faculty and with other students on campus was either essential or highly preferable. Those who were opposed to distance education usually discounted the usefulness of technology entirely:

The availability of communications technology does not make me feel distance education is practical. I think of this technology as retrogression rather than progression. . . . There's nothing worse to me than a telephone conference call. I hate the telephone. . . . It's all totally dehumanizing. . . . You use these things only because you're forced to do it. . . . I don't think they help much. I think they are a kind of one per cent improvement over nothing.

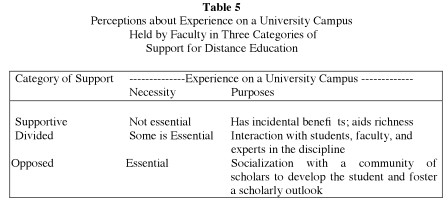

Faculty in the three groups of support for distance education also understood the value and purpose of experience on a university campus differently (see ) and this was consistent with their views about instruction.

Faculty who were supportive of distance education believed experience on a university campus might have some advantages, but that it was not essential. They saw it as a luxury that may have incidental benefits: "The experience of being part of a university, perhaps will round the person out a little bit better. Perhaps. What value that might have I am not sure."

Faculty who were divided in their support for distance education believed that some minimum amount of experience on a university campus was preferred for undergraduates and essential for graduate students. The value of experience on a university campus for most of the divided group was for face-to-face interaction with other students, professors, and visiting scholars within the department and discipline of study. At the graduate level in particular, the purpose of campus experience was for spontaneous, ongoing dialogue within the laboratory and departmental community.

One of the important things as a graduate student is that you get into your department and you talk to the other professors, and . . . other graduate students . . . and its often the peer contact, or the colleagues that you make there, that are just as important a part of the graduate experience as any course you'll ever take or any book you'll ever read. . . . I think you lose that in a distance program.

Faculty who opposed distance education viewed campus experience as essential but for different reasons. They tended to think of university campus experience as the ideal community of scholars where students from a variety of disciplines bumped into each other and debated issues from various points of view. They believed that the university environment at large was important for socialization, the shaping of character, and developing a scholarly outlook:

The university campus experience is one of the most important things students have, just to bump into, to talk, and argue with people from totally different backgrounds. . . . Connections are made between different branches of knowledge and it becomes an opening and broadening experience for students.

Faculty responses to questions about several of the indicators of compatibility and feasibility did not reveal distinct variations according to the extent of their support for distance education. The most notable of these was the university reward system. The majority of the faculty interviewed (43 out of 50) stated that the reward system favoured research over teaching. They believed that faculty would not be recognized for trying different teaching methods of any kind, including distance education. Hence, the reward system was perceived to influence negatively faculty participation in distance education, rather than support it. This finding is a striking example of the often noted conflict between research and teaching for university faculty and of the restraining effect this conflict has on faculty participation in teaching (Becher & Kogan, 1980; Halsey & Trow, 1971; Ross, 1976; Smith, 1991).

The interview data also confirmed the survey findings regarding differences in faculty support for distance education by gender and by disciplinary groupings. In the interviews, women commented more often than men (43% versus 7%) that many women need flexible teaching methods, such as distance education. This suggests that female faculty perceive women as having some special educational needs, consistent with the findings noted in other studies (Anwyl & Bowden, 1986; Schalk, 1984).

The interviews indicated that faculty in the hard, pure (natural sciences) disciplinary grouping may have been significantly less supportive of distance education than the other disciplines because of the emphasis they place on social connectedness. Social connectedness refers to informal relations with colleagues that is characteristic of the natural sciences and appears to be important to their research activities (Becher, 1989; Biglan, 1973).

The study confirmed that there is a great deal of scepticism about the credibility of university distance education. This is a deterrent to the development and expansion of distance education, especially at the graduate level. The results are similar to those of other studies of academics' attitudes towards university expansion (Adamson, 1976; Anwyl & Bowden, 1986; Ballis Lal, 1972; Halsey & Trow, 1971) that found faculty do not envision any major change or transformation in the provision of higher education. The findings also correspond with Johnson's (1978) conclusion that faculty perceptions about accessibility to university education and educational quality create a value conflict for many faculty.

Although most faculty were not very familiar with distance education, they had definite opinions about it that they were willing to express. This confirmed the assumption that faculty may influence committee decisions about proposals to offer distance education even though they have little knowledge about or involvement in distance education. This characteristic feature of academic governance makes program approval particularly difficult. Jevons (1990) claims that distance education is often dismissed on the grounds of prejudice. Webster's dictionary defines prejudice as "an opinion or leaning adverse to anything without just grounds or before sufficient knowledge." Based on their overall lack of knowledge about distance education, the results of this study suggest that many faculty have a propensity to act in a prejudiced manner towards distance education proposals.

The faculty interviewed linked their concerns about the quality of distance education to the process of education, specifically to the importance of transactions between students and teacher, and among students on a university campus. The separation of teacher and learner was the biggest issue and they used the norms of conventional educational practices, plus their own experience as university students, as the basis for their opinions about distance education. This finding supports the approach of Garrison & Shale (1990) that distance education must be considered as an educational process with the transaction between teacher and student as its basic feature. Distance education methods emphasize how this transaction can be facilitated when the teaching and learning acts are separated by time and place. The faculty interviewed believed that dialogue and academic dis-course are necessary features of education that must be assured in distance education in order to achieve quality. Many faculty also believe that the social aspects of learning are very important to educational quality.

The different beliefs and values held by academics regarding university education have implications for educational planning in general as well as for distance education specifically. The great diversity of opinions and the many disciplinary subcultures in universities make it difficult to obtain agreement on proposals for strategic plans, mission statements, and educational policy changes of any kind (Becher, 1989; Bryson, 1988; Clark, 1987; Gaff & Wilson, 1971; Sibley, 1986). Faculty in this study thought of university education in relation to the values of elite, mass, and mixed phase education (Trow, 1973). However, faculty may have common values that they choose to realize in different ways (Gaff & Wilson, 1971). The challenge for planners is to find common values within the different views of university education that may be addressed and accommodated in the planning process. More specifically, the tension between egalitarian goals and excellence must be resolved so that they are seen as compatible because real equality is only achieved through excellence (Schaefer, 1990).

Most faculty in this study valued both accessibility and quality. Faculty in the three different categories of support for distance education believed that quality could be achieved in different ways. Faculty believe that face-to-face interaction and experience on a university campus are important aspects of quality. Many expressed concern about the erosion of these aspects of education in general, aside from their reservations about the quality of distance education. Accessibility was also a common concern and faculty, in the divided group especially, experienced a conflict of values because they did not want to trade-off quality for accessibility. Articulation of these common values and how they are addressed in planning proposals may help to allay faculty concerns that these values are overlooked or that one is traded off for the other.

The results indicate that the planning and implementation of distance education may be facilitated by increasing faculty familiarity with distance education. Faculty who are more familiar with distance education are also more supportive of it. More information about distance education may help make it credible in the eyes of academics and decrease their concerns about quality. Verduin and Clark (1991) claim that increasing faculty knowledge about distance education is the key to gaining acceptability. Faculty need information about the emphasis distance education theorists place on dialogue and discourse in distance education (such as that noted by Chance & Bates, 1991; Garrison & Shale, 1990; Holmberg, 1991; Keegan, 1990; and Moore, 1990) in order to believe that there is sufficient concern for the quality of the educational process as opposed to the distribution of information in distance education. There is a large divided group who may support distance education provided they are assured that requirements for face-to-face interaction, laboratory work, and campus experiences are addressed.

Information about and proposals for distance education should address how face-to-face interaction and campus experience requirements are handled because these are the main concerns academics have about quality. Many fear that a lack of immediacy and spontaneity in interaction is a serious limitation of distance education. They also worry that distance students will miss the stimulation and challenge of group discussions with other students. Faculty must be assured that distance education courses cover more than factual material, have a theoretical basis, and lead to a critical understanding and appreciation of the material. The differences between independent study and student isolation need to be clarified. The benefits of and problems with communications technology should be discussed and the "humanizing" techniques developed for distance education highlighted. Information sessions or seminars on distance education should attempt to have the participation of members from each discipline. There was some evidence in the interviews that faculty who are opposed to distance education may listen to the views of respected others in their discipline. This concurs with the change literature that respected people influence others to try new things (Rogers, 1983).

The report of the recent Commission of Inquiry on Canadian University Education (Smith, 1991, p. 31) noted a dangerous trend in Canada towards the quantity of research publications becoming more important to the careers of university professors than the excellence of their teaching. The results of the faculty interviews indicated that faculty perceive this as not just a trend but a reality that they would like to see reversed in favour of more balance in the recognition given for both teaching and research. The implementation of distance education could be facilitated by providing more incentives to faculty for teaching in general.

The study was limited to one site and no attempts were made to obtain results that would generalize to other universities. Research in other conventional universities with a different history is recommended to determine if there are different factors in other settings that influence faculty support for and participation in distance education. The "newer" universities likely have a different organizational saga or "a unified set of publicly expressed beliefs about the formal group that (a) is rooted in history, (b) claims unique accomplishment, and (c) is held with sentiment by the group" (Clark, 1977, p. 100). A different sense of purpose and commitments may account for the greater involvement of some universities in distance education. This may include more adherence to the notion of mass education both organization-ally and individually within the institution.

Several sources of measurement error are also limitations of the study. Subjects responded to the questionnaire on the basis of hypothetical questions and they might act differently in a real life situation. Faculty who were opposed to distance education, based on the survey, were less likely to agree to be interviewed than supportive faculty. Subjects who expressed elitist views during the interviews tended to apologize for what they felt may be traditional, outdated beliefs. Hence, opposition to distance education may be underestimated by this study because it may be biased towards a more positive group. Researcher bias in the collection and interpretation of data is another possible limitation.

The transition from elite to mass higher education, with its tremendous growth in the numbers of both faculty and students from more diverse backgrounds, results in a greater variety of notions about what university education should be and whom it should serve. Decisions cannot be easily made on the basis of shared views, instead a variety of beliefs and values held by different groups creates continual conflict (Trow, 1973, p. 17). The results of this study suggest that this applies to the controversy about the credibility of distance education for university degree studies. Faculty support for distance education varies according to the views they hold about university education, its functions, and acceptable forms of instruction. Those who support distance education unconditionally subscribe to a mass system of higher education whereas those who are opposed think of university education in elite terms. Those who were divided in their support for distance education fall in between the two.

The results indicate that there is a great deal of scepticism about distance education that must be overcome before it will be viewed as acceptable by the majority of faculty in a conventional university. The study concluded that faculty support for distance education was largely determined by factors related to the compatibility of distance education with faculty beliefs and values about the purposes of higher education and what constitutes a university education in general. Faculty beliefs about how accessible university education should be for people and the importance of face-to-face interaction and university campus experience were the most important factors. Feasibility factors regarding the practicalities of implementation would influence faculty participation in distance education rather than their support for it as defined in this study.

The results have implications for educational planning in general by indicating the importance of addressing the different conceptions of university education held by faculty. The findings indicate that increased faculty support for distance education may be fostered by increasing faculty familiarity with distance education, especially with methods that help achieve personalized, spontaneous interaction. Until faculty know more about distance education and its concern for the interactional processes of education, the acceptance, development, and expansion of distance education, especially at the graduate level, will be slow and fraught with controversy. Faculty incentives in terms of rewards applicable to tenure and promotion would likely be the most important way to encourage faculty participation in distance education or in alternate teaching methods of any kind.

The author gratefully acknowledges the University of British Columbia and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for their financial assistance during this research.

Adamson, H. (1976). Undergraduate education in the biological sciences in Australian Universities. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Macquarie University, Australia.

Allen, R. (1960). Must home study be a stepchild of education? Home Study Review, 1(1), 15.

Anwyl, J., & Bowden, J. (1986). Attitudes of Australian university and college academics to some access and equity issues, including distance education. Distance Education, 7(1), 106–128.

Ballis Lal, B. (1972). University teachers' attitudes towards expansion. Universities Quarterly, 27(1), 46–65.

Becher, T. (1989). Academic tribes and territories: Intellectual inquiry and the cultures of disciplines. Milton Keynes, UK: The Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Becher, T., & Kogan, M. (1980). Process and structure in higher education. London: Heinemann.

Biglan, A. (1973). The characteristics of subject matter in different academic areas. Journal of Applied Psychology, 57(3), 195–203.

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bryson, J. M. (1988). Strategic planning for public and nonprofit organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Burnham, B. R. (1988). Changing roles in education and training. Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Conference on Teaching at a Distance (pp. 67–71). Madison, Wisconsin.

Calvert, J. (1986). Research in Canadian distance education. In I. Mugridge & D. Kaufman (Eds.), Distance education in Canada (pp. 94–109). London: Croom Helm.

Chance, L., & Bates, R. (1991). Academic socialization and the off-campus student. Continuing Higher Education Review, 55(1 & 2), 86–89.

Clark, B. R. (1977). The organizational saga in higher education. In G. L. Riley & J. V. Baldridge (Eds.), Governing academic organizations: New problems, new perspectives. Berkeley, CA: McCutchan.

Clark, B. R. (1983). Values in higher education: Conflict and accommodation. Tuscon, AZ: Center for the Study of Higher Education.

Clark, B. R. (Ed.). (1987). The academic profession: National, disciplinary and institutional settings. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Clark, R. G., Soliman, M. H., & Sungalia, H. M. (1984). Staff perceptions of external versus internal teaching and staff development. Distance Education, 5(1), 84–92.

Gaff, J. G., & Wilson, R. C. (1971). Faculty cultures and interdisciplinary studies. Journal of Higher Education, XLII(3), 186–201.

Garrison, D. R., & Shale, D. (1990). A new framework and perspective. In D. R. Garrison & D. Shale (Eds.), Education at a distance: From issues to practice (pp. 123–134). Malabar, FL: Krieger.

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. Newbury Park: Sage.

Halsey, A. H., & Trow, M. (1971). The British academics. London: Faber. Holmberg, B. (1991). Testable theory based on discourse and empathy. Open Learning, 6(2), 44–46.

Jevons, F. (1990). Blurring the boundaries: Parity and convergence. In D. R. Garrison & D. Shale (Eds.), Education at a distance: From issues to practice (pp. 135–144). Malabar, FL: Krieger.

Johnson, L. G. (1978). Receptivity and resistance: Faculty response to the external degree program at the University of Michigan (Doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan, 1978). Dissertation Abstracts International, 39, 702A.

Johnson, L. G. (1984). Faculty receptivity to an innovation. Journal of Higher Education, 55(4), 481–499.

Keegan, D. (1990). The foundations of distance education (2nd Ed.). London: Routledge.

Kirby, D. M. (1988). The next frontier: Graduate education at a distance. Journal of Distance Education, 3(2), 115–121.

Kirby, D., & Garrison, D. R. (1990). Graduate distance education: A question of communication? Canadian Journal of University Continuing Education, 16(1), 25–36.

Leslie, P. M. (1980). Canadian universities 1980 and beyond: Enrolment, structural change and finance. Ottawa: Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada.

Lindquist, J. (1974). Political linkage: The academic-innovation process. Journal of Higher Education, XLV(5), 323–343.

MacKenzie, O., & Christensen, E. L. (1971). (Eds.), The changing world of correspondence study: International readings. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

McQuire, S. M. (1988). Learning the ropes: Academics in a distance education university. Journal of Distance Education, 3(1), 57–72.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1984). Qualitative data analysis. Beverley Hills, CA: Sage.

Moore, M. (1990). Recent contributions to the theory of distance education. Open Learning, 5(3), 10–15.

Parer, M. S., Croker, S., & Shaw, B. (1988). Institutional support and rewards for academic staff involved in distance education. Victoria, Australia: Centre for Distance Learning, Gippsland Institute.

Perry, W. (1984). Distance education: Trends worldwide. In G. van Enekevort, K. Harry, P. Morin, & H. G. Schutze (Eds.), Distance higher education and the adult learner (pp. 15–21). Heerlen: Dutch Open University.

Rishante, J. S. (1985). An investigation into the attitudes of Nigerian academics toward a distance education innovation (Doctoral dissertation, Syracuse University, 1985). Dissertation Abstracts International, 47, 438A.

Rogers, E. M. (1983). Diffusion of innovations (3rd ed.). New York: The Free Press.

Ross, M. G. (1976). The university: The anatomy of academe. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Schaefer, T. E. (1990). One more time: How do you get both equality and excellence in education? The Journal of Educational Thought, 24(1), 39–51.

Schalk, N. A. (1984). Faculty attitudes toward continuing education in four selected Texas higher education institutions (Doctoral dissertation, Texas Tech. University, 1984). Dissertation Abstracts International, 45, 3079A.

Scriven, B. (1986). Staff attitudes to external studies. Media in Education and Development, 19(4), 178–182.

Siaciwena, R. M. C. (1989). Staff attitudes towards distance education at the University of Zambia. Journal of Distance Education, IV(2), 47–62.

Sibley, W. M. (1986). Strategic planning and management for change. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 16(2), 81–101.

Smith, S. L. (1991). Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Canadian University Education. Ottawa: Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada.

Stein, L. S. (1961). Is home study a stepchild? Home Study Review, 2, 29–40.

Stinehart, K. A. (1987). Factors affecting faculty attitudes towards distance teaching (Doctoral dissertation, Iowa State University, 1987). Dissertations Abstracts International, 47(7), 1746A.

Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, J. C., & White, V. J. (1991). Faculty attitudes towards teaching in the distance education mode: An exploratory investigation. Research in Distance Education, 3(3), 7–11.

Thompson, M. E., & Brewster, D. A. (1978). Faculty behaviour in low-paradigm versus high- paradigm disciplines: A case study. Research in Higher Education, 8, 169–175.

Trow, M. (1973). Problems in the transition from elite to mass higher education. Carnegie Commission on Higher Education, Novota, CA: McGraw-Hill.

Trow, M. (1987). Academic standards and mass higher education. Higher Education Quarterly, 41(3), 268–292.

Verduin, J. R., & Clark, T. A. (1991). Distance education: The foundations of effective practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Wedemeyer, C. A. (1981). Learning at the back door: Reflections on nontraditional learning in the lifespan. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin.

Willen, B. (1981). Distance education at Swedish universities: An evaluation of the experimental programme and a follow-up study (Uppsala Studies in Education 16). Uppsala: Almquist & Wiksell International.

E. Joyce Black is an Assistant Professor at Dalhousie University School of Nursing in Halifax, Nova Scotia. She recently completed her Ed.D. in Educational Administration/Higher Education at the University of British Columbia. This article is based on her dissertation research. Copies of the questionnaire are available from the author.