VOL. 23, No. 1, 89-106

The implementation of both blended learning and web-based programs is becoming more prevalent within higher education in Canada. Thus, there is increasing reliance upon e-learning tools to support student learning in a variety of teaching environments. Typically, budgetary and programmatic decisions regarding the investment of e-learning resources are made by information technology (IT) administrators and/or professors. However, students are the primary beneficiaries of most IT investments. This study examined Business and IT students' usage patterns and perceptions related to a suite of e-learning tools through open ended and Likert scale survey questions. Findings will assist post-secondary decision-makers in prioritizing IT investments. Further, study results will ensure that the design and implementation of e-learning tools address the needs and usage patterns of the primary client-the student.

L’implantation des programmes d’apprentissage hybride et basés sur le Web devient de plus en plus courante dans les études supérieures au Canada. Donc, il y a une plus grande utilisation des outils eLearning pour soutenir l’apprentissage étudiant dans une variété d’environnements d’enseignement. Typiquement, les décisions touchant les budgets et les programmes concernant l’investissement de ressources en eLearning sont prises par les administrateurs des services de technologie de l’information (IT) et/ou des professeurs. Cependant, les étudiantes et les étudiants sont les premiers bénéficiaires de la plupart des investissements en IT. Cette étude examine les profils d’utilisation d’étudiants en commerce et en technologie de l’information des outils eLearning mis à leur disposition, grâce à des questions ouvertes et à un sondage utilisant une échelle de Likert. De plus, les résultats de l’étude permettront de s’assurer que le design et l’implantation d’outils eLearning répondent aux besoins et au profil d’usager du premier concerné, l’étudiant.

Blended learning has gained increased attention within higher education. Cook, Owston and Garrison (2004) postulated that the growth of blended learning options in Canada was due to a variety of factors: increasing demands from students for instructional flexibility; widespread adoption of learning management systems at the post-secondary level; and the information and communication technologies (ICT) infrastructure currently available on many campuses. Graham (2006) discussed the diversity of blended learning options that combine face-to-face (F2F) instruction with online activities. While agreeing with Cook et al. (2004) that blended learning is a response to students' demands for learning flexibility, and to escalating faculty interest in the instructional use of ICT, Graham (2006) suggested that increased access, improved pedagogy and institutional cost-effectiveness were all significant factors for expanding blended learning opportunities.

A recent study regarding blending F2F and online learning (Vaughn, 2007) described blended learning as the growth of new instructional practices occurring within higher education. However, Vaughn raised important questions about terminology, questioning whether the many variants of new pedagogical practices were indeed "blended." In quoting Williams (2003) who observed that "blended learning has been in existence since humans started thinking about teaching," Vaughn (2007) suggested that the recent introduction of new ICT has changed our understandings of blended learning. The importance of clarifying terminology through research and reflection was emphasized by Osguthorpe and Graham (2003) who observed that the term "blended learning" was widely used in academic journals and conference presentations.

The increase in blended learning options reflects the current "technological landscape" of post-secondary campuses. Milne (2006) observed that "classrooms are not the only form of learning space" and for many students ICT is a natural and expected aspect of their lives. Recently, Garrison and Vaughn (2007) described blended learning not as "an addition that simply builds another expensive educational layer" but rather as "a fundamental redesign that transforms the structure of, and approach to teaching and learning" (p. 5). Further, the authors noted that blended learning raises fundamental issues about how students learn and how they use resources and tools for learning.

Definitions of Blended Learning

Today, the term blended learning is used to define a myriad of teaching and learning practices. Kerres & De Witt (2003) suggested that| "blended learning is simply a "buzz phrase that is so 'open' that everyone can agree on it." The authors observed that at a practical level blended learning has gained much attention. In contrast, the 'buzz" has not received much notice in theoretical discussions to date. (p. 101).

Blended learning has been defined as the combination of two distinct learning practices in a complementary model (Bleed, 2001). Garrison, Kanuka and Hawes (2002) described blended learning as a practice defined by the movement of face-to-face activities to an online interactive environment. Dziuban, Hartman, and Moskal, (2004) suggested that rather than describing blended learning as a web-infused learning environment and/or as a means to bridge geographic distances, it makes more sense to envision blended learning as a strategy to transform educational practices. Wanger (2006), Oliver, Harrington and Reeves (2006), Graham (2006), Mortera-Gutierrez (2006) and Garrison and Anderson (2003) view blended learning through the lens of interaction between students and between students and faculty.

Less attention has been paid in the literature to how students in blended learning environments interact with learning materials or use course tools within campus settings (Lim, 2002). Garrison and Anderson (1998) described interaction between student and content, instructor and content, and between student and instructor. Stubbs, Martin and Endlar (2006) called on blended learning course designers to "consider the content of the learning materials" (p. 164) as well as the interaction between students and course tools. Gabe, Christopherson and Douglas (2005) indicated that online notes were critical factors in how students learned in F2F settings as well as for students in blended learning environments. To date, the question of how students interact with and utilize online course tools in blended learning environments has not been well researched.

Student Choice and Independence

One aspect of blended learning which has received little attention is how the development of new instructional practices affects students' learning and their choice of learning resources. Dorn (2007) stated, "a clear goal of education is that learners should become like their teachers and 'learn to learn.'" (p. 43) Dorn suggested that students evaluate learning resources; make choices about learning activities; and choose the medium through which they engage with learning.

The notion of self-directed learning and learner control has received considerable attention in the literature. Knowles (1975) asserted that self-directedness was a fundamental characteristic of adult learning. According to this paradigm, student choice is not an abstract concept but one practiced by all undergraduate students. Barone (2006) speculates that the "net generation" has strong preferences for online learning resources including multimedia resources. Further, Barone noted students' resistance to environments that reduce their learning choices: "The 'Net Gen' will not be intimidated into abandoning their preferences for interactive, easily accessible, Web-based information sources. They will simply work around the attempts to force them to revert to the traditional activities" (p. 14-3).

There are currently a paucity of data regarding students' choices of online resources and/or the manner in which learning environments affect students' choices. To better understand how and what choices students make, it is important to examine student use of online resources in various instructional settings. While the conceptualization of the "net generation" has received more media attention and less attention from educational researchers, Lohnes, Wilber, and Kinzer (2008) suggest that there is a need for "sustained examination of how college-age students use digital technologies across their lives, given students' important roles in shaping how new technologies are taken up, changed, modified, and reworked to suit a range of social and literacy practices" (p. 4). This preliminary study is intended to increase understandings of how students use selected online resources for learning.

Setting

The University of Ontario Institute of Technology (UOIT) is Ontario's first laptop university. Established in May 2002, the university was created to address increasing demands for science, technology and engineering graduates in Ontario. Located on the eastern outskirts of the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), the university has from the outset embraced the use of ICT to enhance learning. Described as a "laptop" university, each student leases a laptop computer that is pre-loaded with course specific software. Further, faculty members are provided with laptop computers and all teaching and learning spaces on campus are equipped to maximize the use of ICT.

The design and implementation of blended courses was a natural response to pervasive construction of the university ICT infrastructure. At UOIT, the term "blended learning" defines a constellation of instructional and learning practices. Blended-learning courses are broadly defined by a substitution of classroom lectures with the addition of online activities using the university learning management system. The addition of online activities encompass a range of practices including increased use of online discussion forums, greater opportunities for student interaction with the course instructors, increased availability and use of online course materials including media-rich materials such as video files, audio files, learning objects and enhanced lecture notes using media embedded PowerPoint presentations. Further, blended courses utilize web-based and online library resources to both inform online discussions as well as providing students with choices about learning resources.

The technological infrastructure at UOIT combined with faculty members' adoption of blended learning strategies has contributed to new learning regarding the design and implementation of blended courses with emphasis on online interaction and the development of a rich suite of online learning resources. Faculty efforts in this regard are time-consuming and entail complex decisions (e.g., how to manage institutional expectations further to teaching and research responsibilities). These challenges are significant at UOIT where "research intensiveness" must be balanced with instructional tasks that require faculty to author engaging online materials for blended learning.

Research Questions

This paper will explore selected research findings from a study of second-year business students in blended and F2F learning environments. Five research questions informed the study:

Rationale

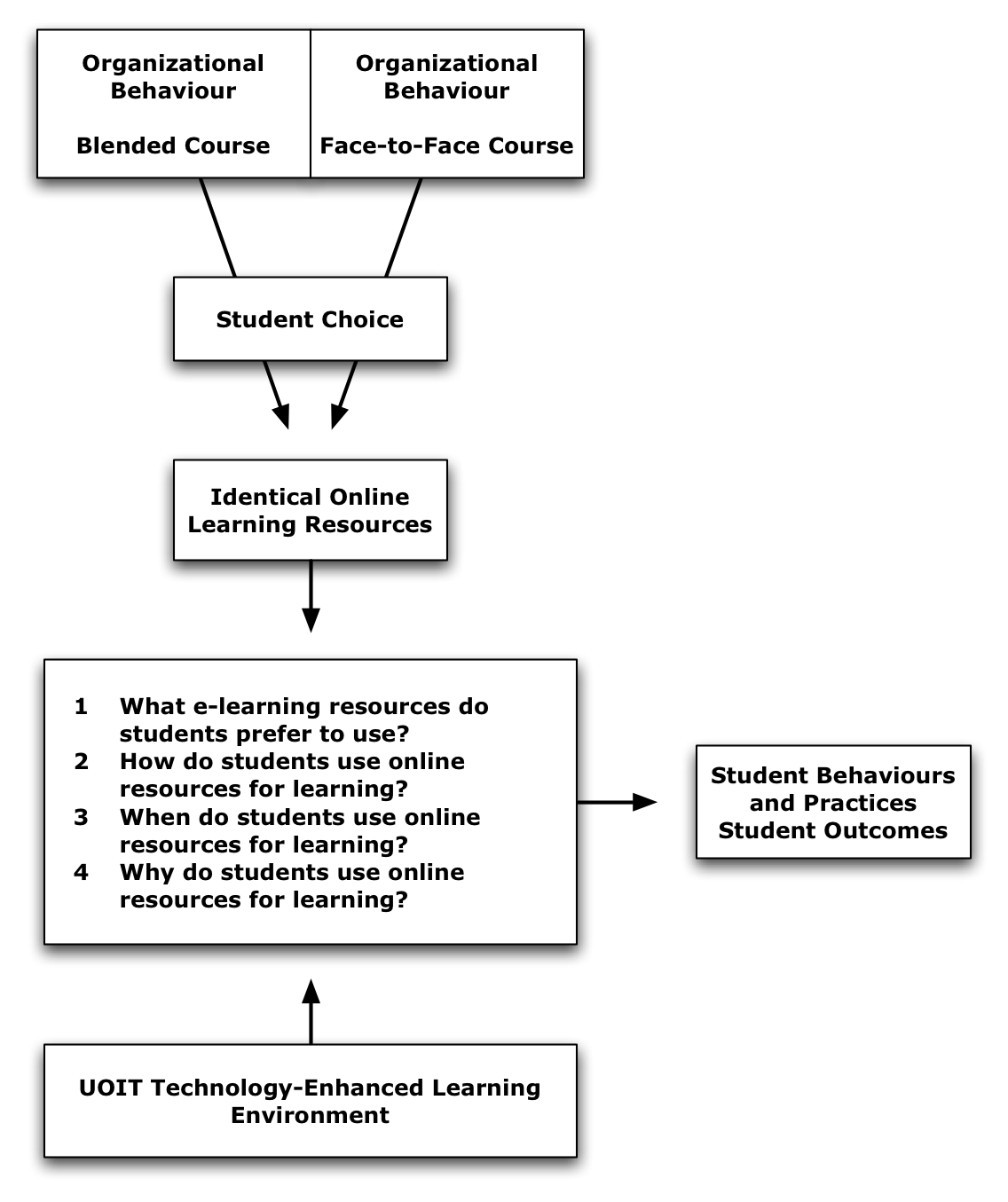

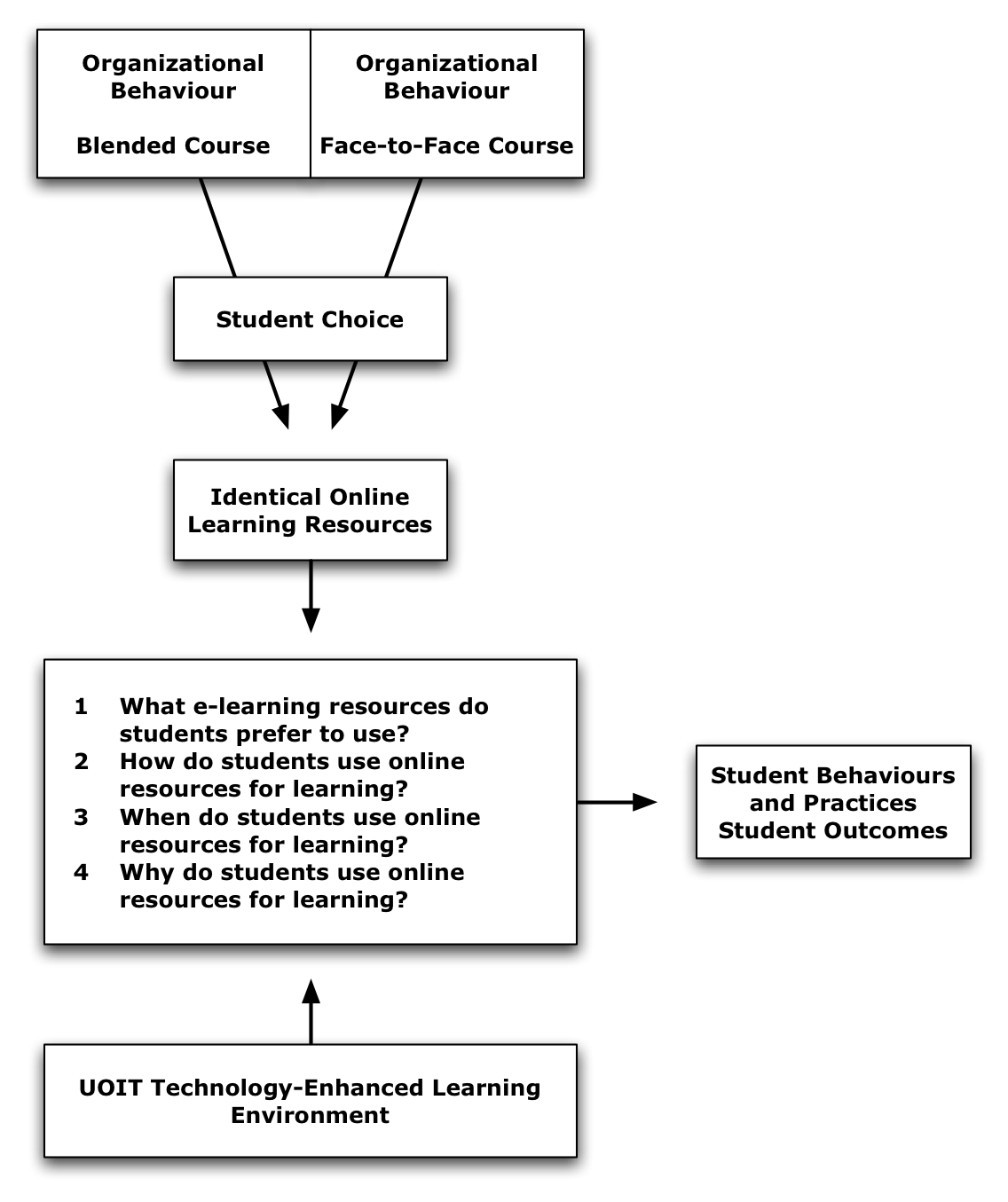

Given the significant institutional and faculty resources dedicated to the use of ICT and e-learning, it is important that academic administrators, and IT professionals better understand which resources aid students in achieving their academic goals. This information will aid in determining where future IT investments should be focused. It is also important to understand when students are using online resources to ensure that they will be available and easily accessible at those times. This data will help determine when online resources should be made available and the potential technical demands on the system. For example, if students use of online learning resources is limited to the completion of assignments, different resources may be required than if students use the resources before lectures to prepare for class. Determining when students access the resources and for what purpose will enable academics to focus their attention on creating effective e-learning tools that are compatible with students' needs. Figure 1 provides an overview of the research study.

Figure 1. Prioritizing the implementation of e-learning tools to enhance the learning environment.

Context

This study uses a convenience sample consisting of all second-year Bachelor of Commerce students taking a core course in organizational behavior. This course is mandatory for second-year business students, and, as well, many students transitioning from 3-year colleges to the UOIT Bachelor of Commerce program are required to take this course. Students were able to self-select whether to enroll in either a blended or an F2F course section. This was the first time that students in the Faculty of Business and Information Technology (FBIT) were introduced to a blended learning environment. Approximately two thirds of the students (136 students) selected the traditional face-to-face section and one third (68 students) selected the blended learning environment. Sixty students in the face-to-face section and 38 in the blended learning section completed the surveys (a response rate of 44% and 56% respectively). Although the response rate was high, we cannot be certain that the survey results represent the entire student population.

The course was designed to make use of the e-learning environment provided by the University by incorporating the use of WebCT, discussion boards, WileyPlus (an online and interactive textbook, self-assessment, and independent student learning system), instructor developed multi-media materials and SecureExam to provide a secure testing environment for online quizzes. Every student was given access to the same set of online resources. All F2F lectures were recorded and made available using Camtasia Studio. This software allows faculty to create “records” of lectures where audio and PowerPoint slides are combined to capture the lecture thus enabling students to review the lecture component of the course on their laptop computers. Instructors “record” the lecture and upload the file to WebCT where students can download the lecture. Each section had its own discussion board for the course, and, as well, as each group had its own private discussion board for collaboration. Students were not forced to use the discussion boards but it was recommended that they be used in order to demonstrate individual work contribution for group assignments. Students were also given the option of purchasing only the electronic version of WileyPlus or purchasing the physical textbook that also included access to WileyPlus (approximately 25% of student selected the online only option). The general course design is described in Table 1.

Table 1. Course Design

Face to Face |

Blended Learning |

| Traditional Lectures | Online lectures using Camtasia Studio presentation recordings |

| Face-to-face student tutorials (Applied Case Analysis) |

Face to face student tutorials (Applied Case Analysis) |

| In-Class mini case discussions | Online group synchronized chat case discussions |

| In-Class and Online Online Self-evaluations | Online Self-evaluations |

| Online quizzes | Online quizzes |

| Use of WileyPlus for reading assignments and e-book | Use of WileyPlus for reading assignments and e-book |

Data Collection

The results from the study are derived primarily from a student survey completed at the end of the term by the students and the technical information obtained from WebCT files. The online survey consisted of sixty questions grouped into nine themes which asked students open-ended and five point Likert scale questions to provide feedback on their use of e-learning tools, as well as their perceptions on areas for improvement and the most important course components for learning. Additionally, the course instructor kept a journal of general classroom observations from which to better document the classroom cultures of each course section. These observations were anecdotal and thus while systematically gathered were not a primary data source for this study. Survey results were analyzed for both “purpose”—what students reported using specific course resources for and the “reason” they chose to use particular resources over other available resources. By comparing frequencies of student usage, mean usage, and student usage patterns, survey results were examined to better understand when and why students chose to use certain resources at certain times during the course. The choice and frequency of resource use was examined to better understand student perceptions of “value” based upon usage patterns of online course materials. The academic performance of the students was derived from their final grades in the course and was included to better understand the impact that technology had on performance.

Results

The study asked students in both the F2F and blended sections about their preference of e-learning resources and some of their reasoning for using these online course resources. Course resources included:

The results for the five research questions are presented and discussed below.

What e-learning resources do students prefer to use?

All students in both the F2F and blended course sections were provided with identical online resources. Resources were made available in the online course sites on a weekly basis or were preloaded into the course at the beginning of the semester. All students were given similar written and oral instructions about the online materials, their value and purpose in the course.

Students reported using online resources for a variety of purposes. The online survey asked students to identify what online resources they used, how often they utilized these resources and for what purpose. Interestingly, except for students listening to lectures once or less, there was little variation in patterns of use between the blended and traditional F2F students. Blended students (17%) listened to lectures recorded by the professors more than once while 16% F2F students listened to recorded lectures more than once. At first glance this seems low for a “podcast-like” resource, and even more surprisingly, 37% of F2F students and 45 % of blended students reported listening to the recorded lectures only once during the course. However, while the survey instrument did not ask specifically ask about why students used or did not use particular resources, further data analysis demonstrated the overwhelming benefit to those students who did review the recorded lectures. Those students (F2F and blended) who reported listening to lectures more than 2 or 3 times achieved substantially higher grades (81% vs. 51%) than those students who did not listen to or use recorded lectures for study purposes The benefit of listening to lectures is likely contributing to increased success, while the general lack of use by students of recorded lectures is a puzzle. Certainly technological issues were not evident and access was not an issue, since all students had access to the course site, laptop computers, and had previous experience with online resources as well as the university LMS. We can hypothesize that the lack of student use of online lecture recordings was, in part, due to students enrolling in a blended course for the first time and the lack of direct experience in how valuable these recordings might be to their learning. Additionally, the insignificant use of the online lecture component may be in part due to recent introduction of this type of learning resource in courses in the FBIT and UOIT generally.

An unexpected finding of this study was how little students in both course sections used the online self-tests provided by the publisher. It was assumed that students would make greater use of this online resource than students reported. Little over half of all blended students (58%) used the online self-testing tool once while 48% of students in the F2F section accessed the tool a single time. Only 5% of F2F students and 3% of blended students reported using this learning asset 4-5 times during the course. In seeking to understand the low use of this tool, we have postulated two possible reasons for low usage/choice. Students may have expected all resources to be available within the university LMS rather than being re-directed to the publisher's website, with a separate login and authentication process. Anecdotal evidence from students and other UOIT faculty suggest that “millennial” or at least UOIT laptop students expect learning settings to reflect the more one-stop “commercial” sites they visit and use daily. Equally, the availability of these resources was “new” to students and that, unlike some observers of millennial students who suggest students naturally gravitate to online resources, students clearly need to be directed to new online resources, be rewarded for their use, as well as clearly seeing the benefits of new types of online resources.

When do students use online resources for learning?

An important factor in better understanding how to manage the workflow of blended courses is to better comprehend when students use particular online course resources. Instructor's efforts to develop learning materials can be directed, in part, by when students make use of online course components. Students reported (19% in F2F and 35% of blended students) making use of online lectures to help complete course assignments. This suggests that these learning assets should be made available as close to the live lecture as possible. Other students (35% F2F and 41% of blended students) chose to primarily use online lecture recordings and online class notes posted to the LMS to prepare for mid-term or final exams. This usage pattern may allow faculty if necessary (due to post-production workflows) to post these elements at set intervals throughout a course, rather than weekly. To seek answers to these questions of usage throughout the course, the survey asked students when they used online resources. Survey results suggest that students primarily used online materials for study purposes. Students responding to the survey (47% F2F and 32% of blended students) reported using the self-tests for study purposes. Additionally, 41% of F2F and 35% of blended students reported using the discussion forum to review faculty posting and student contributions to prepare for formal assessments. Students also reported using forums to collaborate regarding clarification about and expectations regarding course assignments. Students also reported using the discussion forum to work together on case studies as well as preparing for class (60% of blended and 52% of F2F students). The significant use of the discussion forum can in part be attributed to three factors; a) the student ownership of laptop computers; b) Internet connectivity on campus, allowing students to access online course sites anytime/anyplace and c) the pervasive use of discussion forums in all UOIT courses.

Students made significant use of the online course text. Blended students used the e-book more often and for many more purposes than F2F students. Blended students reported using the e-book to complete case studies (45%), to prepare for each week's F2F lecture (37%) and to generally study for the course (41%). In contrast students in the F2F section made significantly less use of the e-book, with only 22% using the online resource to complete case studies, and 29% to review material before a lecture. One reason for this discrepancy may be the “comfort” that blended students had with studying online, as well as the design of the blended course, where more teaching and learning occurred online than in the classroom setting. The significant use of the discussion forums by students both in F2F and blended sections attests to prior use but we surmise that ubiquitous access to computer hardware (laptops) and Internet accessibility across campus may also have been a factor. Questions about whether students who become more familiar with new resources will make greater use of them are unknown. But the mixed adoption of online learning resources by students certainly challenges more accepted notions of students' preference for using rich online learning resources when available.

How do students use online resources for learning?

Student access to online resources is not a sufficient factor from which to draw conclusions about how students use online learning resources. At UOIT the technological and cultural barriers to accessing online resources has been largely eliminated. As well, the notion of access does not measure student engagement or active use of a specific resource. Consequently it is important to understand how students use online resources to comprehend how students choose particular learning resources. Understanding how students use online resources in both blended and F2F settings and whether usage patterns differ can help guide instructors and course designers to better integrate e-learning resources into their teaching practices, and allow instructors to better design and develop e-learning resources for new learning environments.

The results from this study showed that both blended and F2F business students used the discussion forum primarily to communicate with each other as well as determine course expectations. Both blended and F2F students (41% vs. 39%) indicated that they used the discussion board primarily as a reference tool. However, there was a significant difference with respect to using the discussion board for seeking clarification about course assignments. Surprisingly, the use of the discussion board for reference was significantly higher by students in the F2F course (51.7%) than those in the blended learning environment (36.8%). In trying to understand this finding it was hypothesized that blended students were more self-directed and used the online resources to clarify their learning. Anecdotal classroom observation by one of the authors, as well as a review of the length and depth of online discussions by F2F students, appear to support the notion that students who attended classes more often continued discussions begun in F2F settings in the online environments. While classroom observations were incidental to the study, they appeared at face value to confirm that interaction begun in traditional F2F classroom settings continued online, unlike the blended students who appeared to adopt a more independent learning orientation and did not form closer relationships from the F2F setting (in part due to meeting face-to-face only six times during the semester). This will be a question for future research and will be investigated further in the next stage of this research study. The availability of self-tests, sample online quizzes, and online self-assessment exercises proved to be very popular for students to use, read, and as a reference for course concepts and material. Students in both learning environments similarly engaged in using these e-learning resources for reference, reading, and even taking notes on the self-assessment exercises. These results demonstrate that students in any type of learning environment will use these supplementary resources in comparable ways to enhance their own learning, if the resources are made available to them.

The use of lecture recordings and online reading assignments from the e-book were used by a significant number of students to read, take notes, and for some as a reference. As expected, a much larger number of students in the blended learning environment (53% of blended students vs. 31% of F2F) used the online readings and lecture recordings to take notes than students in the F2F environment who had the opportunity to take notes in the face-to-face lecture. Similarly, a much larger percentage of students in the blended learning environment used the online reading assignments for reference, when working on assignments, cases, and in preparation for exams. The importance of these tools to all students for reading/listening to the course content and for taking notes on the course material is clear.

Why do students use online resources for learning?

This research question is intimately linked to the previous question about how students use the resources. Once we have a clear understanding of what forms of e-learning tools student prefer and how and when they prefer to use them, we then need to understand why they are selecting each online resource to possibly help instructors to better create activities for students. The results of knowing why students use particular learning resources can result in more productive use of faculty time as they prioritize the preparation of the resources that students are most likely to use.

When asked about why students selected to use the textbook, the results are almost identical for the F2F and blended learning environments. This is a resource that students are comfortable with from past experience and they know that it will help them achieve the academic success they are looking for. Blended students (60.5%) and F2F students (65.5%) reported the convenience of using a textbook as the primary reason for the e-text. Many cited their previous experience with using textbooks (50 and 51% respectfully).

However, the results for why students who used lecture recordings were different. More students in the blended learning (21%) section had previous experience with lecture recordings than in the F2F class (6%). Familiarity with a larger variety of online resources may be one factor in the choice by some students to selected the blended learning environment as they were already more comfortable with practices and online resources normally found in distance and/or online learning environments. However, much literature suggests that factors such as flexibility, family commitments and personal factors are important factors in choosing less structured learning environments.

The reasons students reported for completing practice quizzes and self-tests were overwhelmingly the convenience of using the resources and the similarity that the questions had to those on their weekly quizzes (34% and 36%). This is an important finding, since it encourages instructors to create self-tests and practice quizzes as enhancements and study aids for students. Students' responses indicate that as long as accessing the practice quizzes is easy, they will spend time to practice on their own. The instant feedback provided by the practice quizzes and self-tests allowed students to test their knowledge and focus their studying on the areas where they have identified themselves as being weak.

As students gain more experience with the various forms of e-learning tools more selective usage patterns may emerge. For many students in this study, this blended course was the first time they had been exposed to a large number of e-learning resources. Future research will need to look at the longitudinal impact of using e-learning resources in the classroom in order to identify which tools are used regularly by students, which types of new resources they request to be made available, and which types of resources are used only for certain types of applications and/or courses.

The implications of student use and choice of online learning resources in both blended and traditional settings are important to institutional allocations of resources and to better understanding what students believe are helpful and choose to use and inform their learning outcomes. The results of this study raise important questions about student choice and use of online resources. The surprisingly small use of course casts (podcasts of F2F lectures) was surprising. It was expected that given the widespread interest in podcasting and considerable discussion among both students and faculty regarding capturing and distributing F2F lectures that greater use by students would have been observed. While few students listened to all the online lectures/podcasts, those that did achieved significantly higher grades than those who either did not listen or only listened to the lectures once. While it is theorized that students may need greater familiarity with podcasts and their benefits to make greater use, the results also speak to the need to both recommend students use new online resources but to also offer some incentives for doing so. It is apparent that while "millennial" students maybe early adopters of some types of new technologies, it cannot be generalized that students automatically adopt or are predisposed to using new resources simply because they are made available.

A second finding from this study was the observed and anecdotal evidence that students expect online course sites to mimic the "commercial" sites they most frequently visit. This was true for both students from F2F and blended course settings. One student wrote "it would be really helpful if teachers and TAs post more often and keep everything we need to know in WebCT and not on their own websites, etc." Students remarked that they expected a complete seamless online course site in the university LMS rather than being either re-directed to another site or to the requirement to re-authenticate to access additional learning resources. Where this was required students reported choosing less often to use those resources.

In reviewing patterns of usage between students in F2F and blended settings, it was interesting to note the similarity of student use. Except for blended students who made a) greater use of the e-book for making study notes or to use course podcasts to assist in studying for quizzes, b) reported listening to lectures more often and c) used the discussion forum less to continue discussions begun in the lecture, students made similar choices about how to use online resources. The findings suggest that faculty who make efforts to adopt and develop new online learning resources within their teaching practices will find that students will make the transition from traditional classroom settings to blended settings once they become more familiar with the resources and their benefits.

This study has demonstrated that students are demanding a greater degree of flexibility for learning in both blended learning and traditional F2F environments through their diverse use and high demand for self-tests, discussion boards, and lecture recordings. When asked what they would like to see available in the future students responded they were not content with the status quo. A student from the blended course section wrote "I would recommend adding teacher conferencing over the online chat so people who cannot make it into the office hours can get help from home." This demonstrates the willingness students have to use e-learning tools as well as online resources if they will allow students increased flexibility and access to support when they need it.

Changing the pedagogy of teaching traditional courses will require additional resources to create, improve, and support both the technical and human resources infrastructure. Increasing the diversity of the student populations and diversity of pedagogical approaches will create new complexities for the academic enterprise. Academic leaders and faculty members must work together to create a learning environment that is not defined entirely by the physical campus of the institution but is a blend of both the physical campus and the online neighborhood, created by the e-learning resources and online tools available on many campuses. Both faculty and institutional leaders will need to monitor student use of online resources to better understand how best to advise students about their availability in a variety of learning environments, and how to use these new materials in a meaningful way.

Lastly, while this study identified how students used and reported choosing online resources in an F2F and a blended learning environment, it is unclear how growing familiarity with new learning resources, increased experience with new learning typologies and new technologies may affect what kinds of resources most positively affect learning outcomes. Further research is needed into how students make learning resource choices in the kinds of learning environments where ubiquitous Internet access, ICT infrastructure and rich learning media are being developed.

Barone, C. (2006). The New Academy. In Oblinger D. G. & Oblinger, J. L. (Eds), Educating the net generation. Educause. Retrieved February 4, 2008 from: http://www.educause.edu/educatingthenetgen

Bleed, R. (2001). A hybrid campus for a new millennium. Educause Review, 36(1), 16-24.

Cook, K., Owston, R., & Garrison, D.R. (2004). Blended learning practices at COHERE universities. York Institute for Research on Learning Technologies, Technical Report 2004-5.

Dron, J. (2007). Control and constraint in e-learning: Choosing when to choose. Idea Group, Hershey, PA.

Dziuban, H., & Moskal, P. (2004, March). Blended learning. E-Center for Applied Research Bulletin, (7), 1-12.

Gabe M., Christopherson, K., & Douglas, J. (2005). Providing introductory psychology students access to online lecture notes: the relationship of notes use to performance and class attendance. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 33(3), 295-308.

Graham, C. R. (2006). Blended learning systems: Definition, current trends, and future direction. In C. J. Bonk & C. R. Graham (Eds.), The handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs (pp. 3-21). San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

Garrison, D. R., Kanuka, H., & Hawes, D. (2003). Blended learning: Archetypes for more effective undergraduate learning experiences. Presentation at the Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. June 2003, Vancouver, Canada.

Garrison, D. R., & Anderson, T. (2003). E-learning in the 21st century: A framework for research and practice. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Garrison, D.R., & Vaughan, N. D. (2008). Blended learning in higher education: Frameworks, principles, and guidelines. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kerres, M., & De Witt, D. (2003). A didactical framework for design of blended learning arrangements. Journal of Educational Media, 28(2-3), 101-113.

Knowles, M, S., (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. New York: Association Press.

Lim, D. H. (2002). Perceived differences between classroom and distance education: Seeking instructional strategies for learning applications. International Journal of Educational Technology, 3(1). Retrieved March 10, 2007 from: http://www.ed.uiuc.edu/ijet/v3n1/d-lim/index.html

Lohnes, S., Wilber, D., & Kinzer, C. (2008, January 01). A Brave New World: Understanding the Net Generation through their eyes. Educational Technology Magazine: The Magazine for Managers of Change in Education [serial online], 48(1), 21. Retrieved June 15, 2008 from ERIC.

Milne, A. J. (2006). Designing student learning space to the student experience. In D.J. Oblinger (Ed.), Learning spaces. Educause. Retrieved February 4, 2008 from: http://www.educause.edu/LearningSpaces/10569

Mortera-Gutierrez, F. (2006). Faculty best practices using blended learning in e-learning and face-to-face instruction. International Journal on E-Learning, 5(3), 313-337.

Oliver, R., Harrington, J., & Reeves, T.C. (2006). Creating authentic learning environments through blended learning approaches. In C. J. Bonk & C. R. Graham (Eds.), The handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs (pp. 502-516). San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

Osguthorpe, R. T., & Graham, C.R. (2003). Blended learning environments: Definitions and directions. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 4(3), 227-233.

Stubbs M., Martin, I., & Endlar. L. (2006). The structuration of blended learning: Putting design principles into practice. British Journal of Educational Technology, 37(2), 163-175.

Vaughn, N. (2007). Perspectives on blended learning in higher education. International Journal on E-Learning, 6(1), 81-95.

Wanger, E. D. (2006). On designing interactive experiences for the next generation of blended learning. In C. J. Bonk & C. R. Graham (Eds.), The handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs (pp. 41-56). San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

Williams, J. (2003). Blending into the background. E-Learning Age Magazine, (1).

Dr. Jennifer Percival is currently an assistant professor in the Faculty of Business and Information Technology at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology. Jennifer teaches courses in organizational behaviour, information systems, and the external environment of business. Her research is focused on the complementarities between e-learning resources in blended learning environments. E-mail: jennifer.percival@uoit.ca

Dr. Bill Muirhead is currently the Associate Provost, Teaching and Learning at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology. Bill has extensive experience in teacher training, online education and course development. His current research is focused on online education, distance education and the design of blended teaching-learning environments. E-mail: bill.muirhead@uoit.ca