VOL. 24, No. 3

The use of WebCT in the Laurentian University Bachelor of Science in Nursing program began in 2001 when faculty were eager to explore different modes of delivery for fourth-year courses. Since then, the use of WebCT within the baccalaureate program has increased substantively. This paper outlines the developmental growth of the use of this Learning Management System in addition to its strengths and challenges as experienced by Laurentian nursing faculty. It furthermore poses questions about the sustained use of existing as well as newer and emerging educational technologies within undergraduate nursing education.

L’utilisation de WebCT dans le programme de premier cycle en sciences infirmières de la Laurentian University a débuté en 2001, alors que les professeurs étaient désireux d’explorer différentes méthodes de diffusion pour les cours de quatrième année. Depuis lors, l’utilisation de WebCT dans le cadre du programme de premier cycle a considérablement augmenté. Cet article dresse un portrait de la croissance développementale de l’utilisation de ce système de gestion de l’apprentissage, de même qu’un portrait de ses points forts et des défis vécus par les professeurs de l’école des sciences infirmières de l’université. On y soulève aussi des questions concernant l’utilisation soutenue de technologies éducatives plus nouvelles et émergentes dans le cadre d’un programme de premier cycle en sciences infirmières.

“Where shall I begin, please your majesty?” (White Rabbit to the King)

In Fall 2001, fourth-year, nursing students at Laurentian University were introduced to their first hybrid course: The course involved three-hour face-to-face classes conducted over the first seven weeks of the semester and web-based communication and learning supported by WebCT tools for the last six weeks. The course also included a face-to-face class during week 13 when students returned to the university to do their final presentations.

As part of the WebCT component of the course, students were required to complete two WebCT bulletin board posting assignments, each worth 20%. These postings laid the foundation for the students’ final presentations. This approach also acted as groundwork for the delivery of a summer externship offered in May 2002, during which time students worked in various clinical locations across Ontario. The fact that they could remain connected to each other and their teacher(s) through WebCT was extremely valuable.

Since 2001, other fourth-year courses have adopted various iterations of this delivery format and, at present, all fourth-year courses are hybrid WebCT courses. Students meet at the beginning of the term and sometimes, depending on the course, at mid-term and end of term. This model supports students’ ability to access out-of-town clinical placements so long as they attend the scheduled in-class sessions. Willett (2002) has found that such hybrid models enable “students and faculty to take advantage of the convenience that distance education offers while still spending some time face-to-face” (p. 414). WebCT is likewise used in other years of the program.

Two experts assisted School of Nursing faculty in incorporating WebCT into the first fourth-year course: An instructional designer and web designer from Laurentian University’s Centre for Continuing Education. At that time, the School of Nursing, through its Director, was working closely with continuing education on a large web-based distance learning initiative called Cardiac Care on the Web. Based on the experience and lessons gained through this project, it became clear to the Director and others that WebCT could be extremely valuable in the undergraduate program. Thus, through a goodwill partnership between the School of Nursing and the Centre for Continuing Education, WebCT found its way into the baccalaureate program.

Instructional design is crucial to the design and delivery of all learning experiences and particularly important to Internet-based and/or technology- enhanced learning environments. Simply described, instructional design is a process used to plan, develop, and evaluate instruction so that it is efficient and effective as well as congruent with the learning theory that acts as scaffolding for the educational exchange. Like the learning it enables, instructional design is not an event but a process which includes “analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation” (Carter, Wiebe, & Boissonneault, 2002).

Brought to undergraduate nursing education, instructional design can facilitate exciting and rewarding pedagogical experiences. For example, nursing education supported by appropriate instructional design decisions can include meaningful interactivity options; students can interact with their content, one another, the instructor, and learning objects. Personal learning activities and opportunities for group sharing can be facilitated through synchronous and asynchronous applications. Online modules including short, self-contained learning exercises can be taken on a mix-and-match basis according to interests, needs, and time constraints. In summary, an online nursing student who is comfortable with an Internet-based learning environment may experience as much interaction as in a face-to-face classroom. He or she will not, however, have to contend with the disadvantages of travelling in inclement weather and studying according to prescriptive schedules. Such interaction—when it occurs in some quantity and is a quality experience—is indicative of constructivist learning (Jonassen, 1999; Moallem, 2001) since the student builds an understanding of content through various avenues and encounters.

Mentoring (Russell, & Perris, 2003) and growth in critical thinking and writing (Carter, & Rukholm, 2008; Carter, Rukholm, Mossey, Viverais-Dresler, Bakker, & Sheehan, 2006) have also been recognized as important outcomes of technology-enhanced learning when there is inclusion of opportunities for personal and group-based communication (Russell, & Perris, 2003). These same benefits have been found to be important for post-certificate nursing students who are typically required to juggle very active personal, professional, and educational lives (Cragg, Andrusyszyn, & Fraser, 2005).

In the case of this initiative, the instructional designer worked with faculty from the School of Nursing and the web developer to determine the primary goal of adding web capacity to the fourth-year courses. Although the immediate goal was not to use WebCT as a teaching and learning modality that would require a high level of technical sophistication, decisions and choices were made such that the potential was there when faculty and students were ready. Instead, the purpose of adding WebCT at that time was to provide a user-friendly means of staying connected; a place where materials could be readily accessed and submitted; and a place where students could share writing-oriented assignments. With this information in “virtual hand,” the instructional designer and web designer could then move to the next step: the development of a web interface and resources to assist faculty and students in their learning about WebCT.

The web design was based on the umbrella principle of providing basic e-communication tools via the simplest interface possible, for the benefit of both faculty and students. Once the necessary e-tools were identified (email, bulletin board, and a content area), the homepage was designed to be a straightforward conduit to these tools; the homepage included a short welcoming message identifying the course code, title, and course instructor, along with the three navigation buttons: Email, Bulletins, Content. The buttons are large for easy clicking, and each displays the e-tool name along with an icon for easy visual identification. The homepage is completed by a top banner displaying the course code, and a footer with the Laurentian University and the School of Nursing logos, each linking to the relevant web site. The colour blue was chosen because it is one of the university’s colours; however, for easier reading, high contrast was integrated. The background colour of both the banners/buttons and the web page itself is the lightest shade of blue available in WebCT (light cyan) while navy is used for the large plain font.

The instructional designer and web developer also developed some easy to follow handouts regarding the use of WebCT. While some might argue that an online tutorial site might have been appropriate, the thinking was that most faculty were new to web-based applications and, therefore, a simple tool that the faculty member could always have available was best. Notably, all of this work was being conducted at the beginning of what Bates (2000) calls an important period of technological changes for post-secondary educator.

“Come, we shall have some fun now” (Alice)

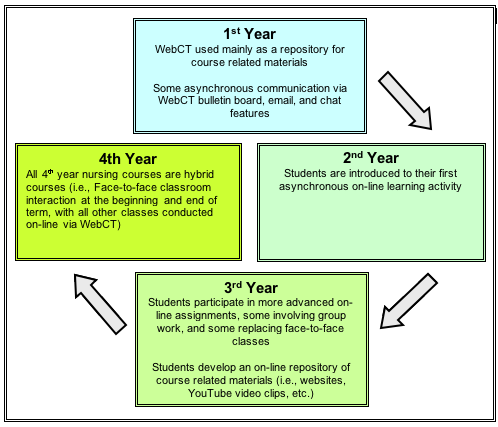

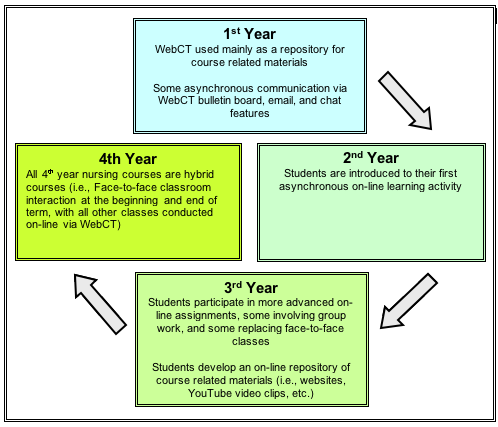

As suggested in Figure 1, WebCT is now being used in a variety of capacities by students and faculty across the BScN program, beginning in first year. Hence, the use of WebCT is now leveled throughout the BScN curriculum with increased utilization as the student progresses through each year.

Figure 1. Leveling of WebCT within the Laurentian University Bachelor of Science in Nursing Program.

As illustrated in Figure 1, first-year nursing is an introductory year in which students receive some instruction on how to use WebCT, and are then expected to use it as a means for accessing various course-related materials such as the course syllabus, outlines for weekly classroom learning activities, a required reading list, and so forth. WebCT also facilitates some communication via bulletin board activity, email, and chat; however at this stage, interactions between the course professor and individual students occur mainly in face-to-face settings.

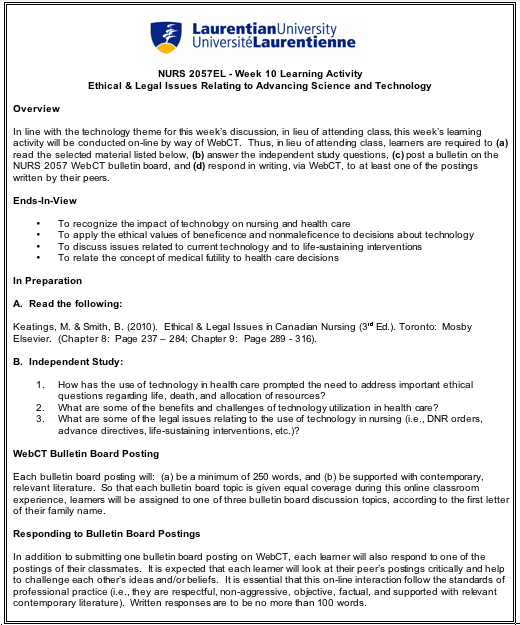

In second year, while the same WebCT applications from first year continue to be used, a few others are also gradually introduced. An example of one such application is an on-line learning activity that has been incorporated into a second-year nursing ethics course. Except for this one particular activity, all other course interactions during second year continue to occur in a traditional face-to-face classroom. An abbreviated version of this particular learning activity is presented in Figure 2.

The decision to modify this previously face-to-face class into an on-line format was not motivated by a conscious desire to level the use of WebCT across the BScN program (although this was recognized as an unplanned secondary benefit later on). Rather, the motivation was to use a variety of teaching methods to appeal to different learning styles, and thereby enhance the overall student learning experience. Implementing an on-line learning activity also seemed reasonable, given the technology theme for this particular class. Turning this class into an on-line event highlights many of the benefits that technology brings to nursing practice, as well as some of the ethical challenges nurses now encounter as a result of technological advances.

Figure 2: NURS 2057EL Ethical and Legal Issues Relating to Advancing Science and Technology

Overall, the students rated this activity as highly satisfactory. When asked the following week to provide written evaluative feedback, they indicated that their on-line classroom experience had been both pleasurable and highly conducive to learning. Students particularly enjoyed the asynchronous nature of the bulletin board, which they believed permitted greater flexibility in terms of being able to decide when (and when not) to participate in class. Staying at home and attending class in pajamas was also cited as a genuine benefit of on-line learning. Many students commented favorably on having time to think before expressing their thoughts on the bulletin board. This, they said, encouraged a much deeper reflection and understanding of the topic than otherwise. It was also suggested by most students that this same level of critical thinking usually did not occur during spontaneous face-to-face classroom discussions.

From a course professor perspective, it was quite surprising to see how quieter students within the class suddenly came to life on the bulletin board. The overall quality of what was written by each student was also very high, possibly at an even higher standard than what might have been verbalized in a face-to-face classroom discussion.

Utilization of WebCT in third year involves the aforementioned tools in addition to more advanced assignments, some of which support group work and, in various cases, replace face-to-face classes. In a third-year professional growth course called Empowerment, students go to their WebCT site to access materials as well as share web sites, YouTube clips, and creative pieces about empowerment. This application has led to the development of a rich repository of teaching and learning objects and resources. Students also use the WebCT site to share plans and materials for group-based workshops.

Finally, as noted earlier in this paper, it is in the fourth year of the program that the majority of face-to-face classes are replaced by WebCT-enabled interactions. This approach was instituted to meet the needs of students who are on placements in various geographical sites across the province. This way, students can remain connected with their teachers and each other despite the barrier of distance. In a study of 328 undergraduate nursing students and 230 graduate nursing students, findings indicated that undergraduate students perceive a need for high levels of student-faculty interaction (Billings, Skiba & Connors, 2005); WebCT is the vehicle for this interaction in the last year of the program.

Venturing into the world of educational technology has been a learning experience in itself for the School of Nursing. The challenges related to including WebCT in the first fourth-year course in 2001 are best expressed as questions: would students be willing to participate in on-line work, post their assignments for all to see, and complete their work to the same standards as they did in face-to-face learning settings? The answers to these questions were surprisingly positive. Students were willing to share information and observations in bulletin board discussions and to respond to postings. Additionally, it is suggested that outcomes included improved interpersonal and communication skills regardless of time and spatial boundaries (Suen, 2005).

Faculty also learned that teacher presence is extremely important in on-line settings. Faculty-student dialogue needs to occur at the beginning of a course and continue throughout the term. Teachers need to encourage students through prompt and positive feedback, thus creating a safe and open learning environment (Zsohar & Smith, 2008; Suen, 2005). The quality of student assignments also improved; the reason suggested for this is that the students had time to prepare and reflect on what they posted for peers and for grading by the teacher.

Faculty who decide to use WebCT need time and support to become accustomed to this type of delivery. For instance, there was an initial misperception by administration and faculty that on-line learning should not take up as much time as face-to-face learning. However, anyone who has taught web-supported courses knows otherwise; such courses often require as much and often more time and attention than face-to-face learning. Some of the reasons are the time spent on preparation of appropriate course materials, student feedback and dialogue, and evaluation of student learning, all of which involve new ways of thinking and working (Willett, 2002; Zsohar & Smith, 2008). In order that WebCT not become all consuming of faculty and student time (the student may have several WebCT courses), boundaries and time-frames must be clearly communicated and maintained. For example, the teacher might advise his or her students that “I will check email and bulletin board postings and respond to students three times per week on Monday, Wednesdays and Fridays between 9:00 am and 5:00 pm.”

Based on the enthusiastic uptake of WebCT by faculty and students, the program now faces an Alice in Wonderland dilemma:

“Which road do I take?" (Alice)"

Where do you want to go?"

"I don't know," Alice answered.

"Then, said the cat, it doesn't matter.”

As one of the most famous exchanges between Alice and the Cheshire cat, this exchange works as a metaphor for the forthcoming decisions that the School of Nursing needs to make about teaching and learning through technology. Some of the particular questions facing the School are as follows: Have we gone as far as we can with WebCT? (In fact, in a certain way we have since WebCT has been assumed by Blackboard and hence, does not exist as WebCT any more.) Where might we go next? What other technologies might complement our present use of a learning management system based on the complexities of undergraduate nursing education?

The appropriate place to start in order to answer these questions is an undergraduate program review and consideration of strategic directions. What the School determines as its curricular future and its key undertakings for the next five years are vital to the decisions it will make about technology, communication, and learning. Certainly, there is little question that technology-enabled education is here to stay and that nursing practice is becoming increasingly more sophisticated in its use of technology. However, based on the plethora of options now available, their costs, strengths and limitations; and the arrival of Web 2.0, it is important to make carefully considered decisions. Whatever the “ed tech” future holds, the School of Nursing at Laurentian University is confident that it has only just begun.

Bates, A.W. (2000). Managing technological change: Strategies for college and university leaders. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Billings, D.M., Skiba, D.J., & Connors, H.R. (2005). Best practices in Web-based courses: Generational differences across undergraduate and graduate nursing students. Journal of Professional Nursing, 21, 126-133.

Carter, L., & Rukholm, E. (2008). The potential of internet-based educational settings in facilitating university-level discipline-specific writing. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 39(3), 133-138.

Carter, L., Rukholm, E., Mossey, S., Viverais-Dresler, G., Bakker, D., & Sheehan, C. (2006). Critical thinking in the online nursing education setting: Raising the bar. Canadian Journal of University Continuing Education, 32(1), 27-46.

Carter, L., Wiebe, N., & Boissonneault, J. (2002, May). Wizards of things teaching and learning, or why your institution needs instructional designers. Paper presented at the Canadian Association for University Continuing Educators (CAUCE) Annual Conference.

Cragg, C.E., Andrusyszyn, M., & Fraser, J. (2005). Support for women taking professional programs by distance education. Journal of Distance Education, 14(1), 1-13.

Carroll, L. (1982). Alice’s adventures in wonderland. In E. Guiliano (Ed.), Lewis Carroll: The complete illustrated works (pp. 1-74). New York: Gramercy Books .

Jonassen, D.H. (1999). Designing constructivist learning environments. In C. M.Reigeluth (Ed.). Instructional design theories and models: A new paradigm of instructional theory (Vol. 2, pp. 215-239). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Moallem, M. (2001). Applying constructivist and objectivist learning theories in the design of a web-based course: Implications for practice. Educational Technology and Society, 4(3), 1436-4522.

Russell, A., & Perris, K. (2003). Telementoring in community nursing: A shift from dyadic to communal models of learning and professional development. Mentoring and Tutoring, 11(2), 227-238.

Suen, L. (2005). Teaching epidemiology using WebCT: Application of the seven principles of good practice. Journal of Nursing Education, 44(3), 143-146.

Willett, H.G. (2002). Not one or the other but both: Hybrid course delivery using WebCT. The Electronic Library, 20(5), 413-419.

Zsohar, H., & Smith, J. A. (2008). Transition from the classroom to the web: Successful strategies for teaching online. Nursing Education Perspectives, 29(1), 23-28.

Emily Donato is an Assistant Professor, Laurentian University School of Nursing. E-mail: edonato@laurentian.ca

Shirlene Hudyma is a Lecturer, Laurentian University School of Nursing. E-mail: shudyma@laurentian.ca

Lorraine Carter is an Assistant Professor, Laurentian University School of Nursing. E-mail: lcarter@laurentian.ca

Catherine Schroeder is an Educational Technology Coordinator, Laurentian University. E-mail: cschroeder@laurentian.ca