VOL. 25, No. 1

The community of inquiry framework (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000) has been an important contribution to the online distance education field and has been useful in providing researchers with the construct of "teaching presence". Teaching presence as described by the framework provides insight into the types of interactions instructors make in online teaching, but is less useful in helping to understand the why’s of instructors’ interactive decisions. In this study, activity theory (Engeström, 1999, 2001) was adopted as a theoretical framework to understand the why’s of teaching presence, revealing a complex negotiation between instructors as subjects and the mediating components of the activity system. The article suggests that a shift to understanding teaching presence within a sociocultural perspective has important implications for teaching and design, as well as the methodologies inherent in the community of inquiry framework. A sociocultural definition of teaching presence is provided in attempt to provide a broader understanding of this construct.

TO COME

A particular interest of distance online education researchers has been the community of inquiry (COI) framework, which was developed for the purpose of taking a closer look at computer-mediated communication (CMC) in educational contexts (Garrison, Anderson, Archer, 2000). Three components in this framework that are deemed to be essential to the creation of formal online learning contexts are social presence, cognitive presence, and teaching presence. Although much of current research that adopts the community of inquiry framework has largely focused on the social presence dimension (e.g., Rourke et al., 1999; Richardson and Swan, 2003), the community of inquiry framework has also been useful in providing researchers with the construct of "teaching presence", used to describe "the design, facilitation, and direction of cognitive and social processes for the purpose of realizing personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes" (Anderson, Rourke, Garrison, Archer, 2001, p. 5).

The elaboration of the teaching presence construct was undertaken not only for the development of an analytic tool to assist the research process into online teaching, but to also to provide a means for instructors to assess, reflect, and subsequently make changes to their own postings (p. 2). Anderson et al. (2001) identify three categories to describe instructor roles in online teaching— instructional design and organization, facilitation, and direct instruction—and their respective indicators. These categories and indicators have been developed into an instrument for the content analysis of discussion forum transcripts.

Although the construct of teaching presence is closely related to research that describes the functions and roles of online teaching (e.g., Berge, 1995; Salmon, 2000; Offir et al., 2003), it differs in a key way: it is seen as an essential component of a community of inquiry. In this sense it provides a broader and more contextualized view of online teaching, in which the students, content, and instructors play a central role in creating the community of inquiry, and of which social presence, cognitive presence, and teaching presence are interdependent. Yet, despite the fact that the community of inquiry framework attempts to go beyond simply describing individual interactions, the construct of teaching presence is a cognitive framing of the instructor, focusing largely on describing what kinds of interactions instructors make in online teaching and learning contexts. In my view, the teaching presence construct is useful at identifying what instructors (and students) do in a community of inquiry but is limited in achieving the purpose claimed by Anderson et al. (2001) at diagnosing problems in online teaching since it does not get at the "whys" related to what Tsang (2004) has called instructors' "interactive decisions". In addition, it is somewhat surprising that although the community of inquiry framework has been developed based on distance education contexts, it currently does not consider the complexities of the community’s global and local contexts, the potential multi-linguistic demands of the teaching and learning contexts, and how power, agency, and identities are negotiated in these multicultural contexts.

In 2008 I completed a multi-case study (Morgan, 2008) that examined the “why’s” of teaching presence. Informed by the concept of teaching presence in the COI, I adopted a sociocultural framework –third generation activity theory- to explore online teaching in international contexts. This article discusses one of the findings of my study on the negotiation of teaching presence in international, online distance education (DE) courses: the influence of instructor conceptualizations on their teaching presence. In discussing this finding, I underline the implications of adopting a sociocultural theoretical approach to understanding online course interactions on the COI framework, and suggest that within this perspective, teaching presence needs to be redefined.

Unlike research that focuses on roles of online instructors (Berge,1995; Paulsen,1995; Mason,1991; Easton, 2003; Coppola, Hiltz and Rotter, 2002;) the community of inquiry framework provides a broader and more contextualized view of online teaching, in which the students, content, and instructors play a central role in creating the community of inquiry (COI), and of which social presence, cognitive presence, and teaching presence are interdependent components. However, the predominant use of content analysis methods in COI and teaching presence research (c.f. Shea, Vickers, and Hayes, 2010, p. 130, for a summary of teaching presence research examining online discussions) has, for the most part, limited the focus to cataloguing and quantifying interactions, and has not taken a closer look at the contextual conditions in which presence take place. As a result, teaching recommendations are sometimes made that might not apply to diverse contexts. For example, Garrison, Anderson and Archer (2000) recommend that discussion topics should last a week or two at the most in order to encourage deep reflection, and small groups should be used to provide greater opportunity for dialogue without producing too many message postings (p. 97). While this recommendation is certainly adopted in many online course designs, it is debateable whether or not it suits different kinds of teachers, students, courses, and online teaching and learning contexts.

Teaching presence research suggests that there are many possible roles and associated behaviours or actions that define online teaching, and these ultimately have an effect on student perceptions and learning. The critical gap in this research is that it doesn't address the decision-making processes that instructors engage in and the reasons for such decisions. In this regard, it is useful to adopt the notion of “interactive decisions”, defined as "decisions made during teaching", and one that has been investigated in f2f contexts by Tsang (2004). In his study, Tsang was interested in the kinds of interactions three ESL teachers made in their teaching of a lesson and the basis for these interactive decisions as it related to their personal practical knowledge (defined as teaching maxims). Although Tsang’s study focused on f2f (and therefore synchronous) classroom teaching, it illustrated how the emergence of various contextual constraints such as lack of time, equipment breakdowns, and miscomprehensions, affected the ability of the instructors to make decisions guided by their personal practical knowledge.

Third Generation Activity Theory

Cultural historical activity theory (AT) (Engeström, 1989, 1999, 2001) provides a way of looking at the complex contexts of online teaching activity and identifying tensions and contradictions that occur between the mediating components of the activity system.

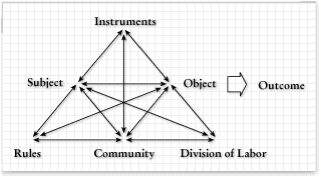

AT is represented visually by a series of embedded triangles representing various mediating components of the activity system. These components include tools or instruments, subject, object, rules, community, and division of labour (roles), as described in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Representation of Third Generation Activity Theory (Engeström, 1987)

AT is distinguished by its focus on a unit of analysis that extends beyond an individual acting in a context. As a unit of analysis, an activity system provides a way to view the practice from a subject’s or multiple subjects’ perspectives (Engeström and Miettinen, 1999, p. 10). AT also provides a way of accounting for and understanding multiple perspectives of the experience and the cultural-historical nature of the practice.

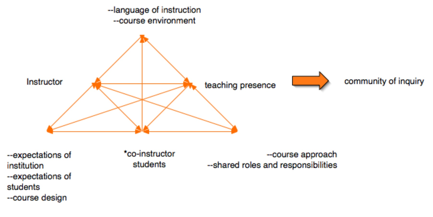

In an AT framework, the community of inquiry can be conceived as the object of an activity system, whose ultimate goal is student learning. Therefore, instructors as subjects and students as subjects are directing their efforts towards student learning in a community of inquiry. COI describes to some extent what this directed effort encompasses—social presence, cognitive presence, and teaching presence—in order for learning to happen. However, as I have argued, it doesn’t adequately describe the negotiation that takes place in achieving this object, which is why AT is particularly useful. When online teaching is viewed from the position of instructors as subjects, the tensions and contradictions that occur in the system can provide a useful description of the negotiation of teaching presence in online courses.

Sociocultural frameworks such as AT and community of practice theory (Lave and Wenger, 1991) fall short of accounting for how individuals or collectives position themselves within these communities and negotiate this positioning. Linehan and McCarthy (2000) shed some light on how the concept of positioning can expand current understandings of sociocultural theories and frameworks. According to Davies and Harre (1990), the concept of positioning attempts to describe how we relate ourselves to our contexts. In Linehan and McCarthy’s (2000) view positioning “is a useful way to characterise the shifting responsibilities and interactive involvements of members in a community” when looking at particular practices (p. 441). This notion seems particularly relevant to online teaching, where instructors arrive in the teaching context with at least some professional identity that has been constructed through experiences in other practices. At the same time, the members of the community (in this case the students) have some notion of the practice of learning and the positioning of themselves in relation to an instructor in that practice. Therefore, dynamics of positioning and identity are already at play at the entry stages of an online teaching context.

Research that employs AT to examine the practice of online teaching have begun to emerge and offer compelling insights into the types of contradictions that can arise (Thorne, 2003; Scanlon and Isroff, 2005; Basharina, Guardado, and Morgan, 2008; Murphy and Rodriguez-Manzanares, 2009), as well as the role of instructor identity in relation to practices (Twiselton, 2004, Sfard and Prusak, 2005; Singh and Richards, 2006). In particular, Fanghanel (2004) used AT as a framework to look at dissonance between teacher education and novice university teachers’ actual practices. She did this by describing the activity system of the novice teacher in training with that of the actual practice setting as interacting activity systems. Her rationale for the use of AT as a framework parallels my own:

By taking account of the interactions between people involved in the activity, structures within which the activity takes place, conventions on which it is based and artefacts used (here, teaching tools and methods), I was able to ground my study in the broad context and capture practice as socially situated, rather than simply evidenced in actions or performance. (p. 579)

Fanghanel’s study underlines the how AT could be used to broaden the analysis of the construct of online teaching beyond a reliance on quantitative content analyses of discussion forum transcripts.

In adopting a sociocultural framework, teaching presenceFN1 is viewed as a negotiation and a practice that occurs within a community of inquiry characterized by constraints and affordances. This study investigated the following research questions:

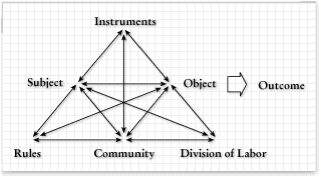

Figure 2 provides a visual description of the activity system of instructors engaged in teaching presence.

Figure 2: Instructor activity system

Although both students and instructors can have teaching presence, the focus of this study was on the teaching presence of the instructor, since the position of instructor itself engenders a different set of power relations and cultural historical understandings. In other words, as Linehan and McCarthy (2000) have noted “both students and teachers have a degree of agency in how they position themselves in interactions but this agency is interlaced with the expectations and history of the community” (p. 442).

I adopted a qualitative multiple case study approach (Stake, 2006) of six cases of teaching presence of online instructors teaching in international contexts at the tertiary level. This study was conducted at three virtual sites. The first site was a post-graduate certificate program situated in Eastern Europe. The second site was a masters program in distance education situated in a South American university. The third site was a graduate program in education situated at a Canadian university with a large group of students located in different parts of the world.

Although there were some variations in the data sources, data collected for each case included:

Data Analysis

Consistent with Stake (2005) each caseFN2 was analyzed separately, beginning with the first interview, then the discussion forum transcripts, and finally the remaining sources of data. Activity theory provided the analytical lens that I brought to the data analysis. Interviews were the starting point for my analysis, and from the themes that emerged I was able to connect them to these guiding frameworks. Once the interviews had been organized into themes, I then began to systematically look at the discussion forum transcripts.

Analysis of the discussion forum transcripts involved several steps. First, I read a printout of each transcript twice, and began making notes in the margins that highlighted significant points or provided interesting evidence of something that an instructor had mentioned in their first interview. I then began looking at the transcript for evidence of patterns in instructor postings, as way to begin characterizing their interactions. I then proceeded to adopt codes for these patterns, and some of these codes were loosely based on Berge’s (1995) typology of instructor interactions. For example, I noted when a posting was of a managerial or technical type. I then began developing my own codes for interaction characteristics that I felt might be significant—asking questions, providing examples, integrating one’s own experience and expertise, etc. This proved to be helpful for some of the cases where the instructor didn’t have their own sense of what characterized their interactions. The discussion forum transcripts primarily were used to triangulate instructors’ statements about their experiences. In many cases, their interpretations matched the evidence provided by the discussion forum posts but, occasionally, an instructor’s understanding of his or her interactions did not match the evidence provided by the discussion forum. When this occurred, it was taken up in the second interview for further exploration.

The second interviews were conducted after this initial analysis and gave me the opportunity to ask further questions that I thought were relevant to understanding the case and to seek clarification. These interviews were generally much shorter—approximately thirty minutes.

The next procedure involved looking at the remaining data that had been collected to inform the case, and to provide a method of triangulation. In particular, CMS data was useful in gaining further insight into instructor interaction characteristics, and course documents provided useful contextual information about the constraints that instructors faced in their courses. Where permission was obtained, student interviews provided a way of understanding student perceptions of teaching presence and the events that occurred during the course. Course evaluations (where obtained) also provided this information. Member checking was used to validate the description of each case.

Findings

One of the main findings was that an instructor’s conceptualization of the online course and its interaction spacesFN3 mediated their teaching presence. I looked for multiple sources of evidence as to how their conceptualizations affected their teaching presence, and whether they were able to realize their conceptualizations.

The courses adopted similar instructional designs, built around weekly readings and content, and supported by a weekly requirement to engage in asynchronous online discussions. Despite this, the range of conceptualizations varied considerably across the six cases. The following table describes how each instructor conceptualized the online interaction spaces in the course they were teaching.

Table 1. Instructor Conceptualizations of the Interaction Spaces in their Online Course.

Case |

Instructor Conceptualization |

Tannis |

Community |

Linda |

Activity space |

William |

Online graduate seminar |

Daniel |

Student-centred online classroom |

Joanne |

Community in the making |

John |

Teacher-directed online classroom |

It is interesting to note that Linda and myself (Tannis) were co-teaching and sharing the same interaction spaces (discussion forum) in the same course, yet we conceptualized the forum differently, with Linda placing greater importance on the outcomes of the forum activities and myself placing a greater importance on the development of community in the forum. Across all cases there was evidence that the way instructors conceptualized the online interaction space had a direct influence on how they negotiated their teaching presence. The constraints and tensions that arose in their respective activity systems influenced the degree to which instructors were able to realize their conceptualizations. Due to space limitations, I provide evidence for three of the cases below.

John - Class Director or Cheerleader?

John was co-teaching a post-graduate course on e-learning to a group of students located in eastern Europe. The course was written and designed by John and the co-instructor Phillip, who are both Canadians working at a Canadian post-secondary institutions. Both John and Phillip subsequently taught the 15-week course in English. This was John’s first online teaching experience.

John conceptualized the online interaction space as a teacher-directed virtual classroom. He had extensive experience in classroom teaching and felt it was important to be a class leader and to be directive in helping students through the course requirements and content. Therefore, he transferred his understanding of the role of a face-to-face instructor to the online context.

John described his approach to online interaction as the following:

In many ways, John’s discussion postings were a conscious attempt to simulate his face-to-face teaching approach, to translate and transfer that experience to the online environment.

John (interview 1): I am looking at [the online environment] as helping people to understand the basic concepts. In any course no matter how constructivist it is you are trying to get something across as an instructor. I am trying to facilitate the learning process, whether that is being quite direct.

Evidence of this directive approach arose in the discussion forum analysis of his communicative style. Whereas some of the other instructors presented in this study consciously used syntactical structures to present a perspective or opinion (e.g., I think, I would suggest, etc.), John frequently adopted more direct structures, as evidenced in the underlined sections below:

Message no. 48[Branch from no. 47]

Posted by John

Subject: Re: Curriculum, Course and instructional design…It's important to rememberFN4 to judge each course/curriculum in light of particular needs, learners, the learning culture of a given institution, etc. There may be times when a "teacher knows best" approach is necessary, at least for a portion of a lesson or course. But even that has to done with a view to maximizing learning.

John.

John experienced tensions in realizing this conceptualization, since he felt his ability to engage as a knowledgeable instructor was challenged by what he perceived as a positioning of himself as a subordinate to Phillip. As a result, he felt he interacted less than he normally would have, and felt that his role and his interactions took on a support and acknowledgement function. The discussion forum data supports this perception. A comparison of John’s postings to Phillip’s shows that while Phillip posted 18% of all messages, John’s accounted for 8% of the total (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparison of Number of Posts by John and Phillip.

|

John |

Phillip |

No. Replies |

31 |

57 |

No. Initiated |

7 |

31 |

Total messages |

38 |

88 |

John had clear ideas about how to occupy a shared role, having also co-taught in face-to-face teaching contexts. His interactions in the discussion forum make frequent reference to Phillip, in an attempt to present himself to the students as a collaborative teaching partner. He does this by including Phillip’s name and those of the students when initiating his messages, and acknowledging what Phillip had contributed to the discussion thus far. John also introduced discussion activities using the united voice of both instructors, as evidenced by his frequent use of the pronoun “we”. John’s teaching presence also deliberately referenced Phillip as way of showing he had read Phillip’s contributions. In fact, John did this nine times of the thirty-eight messages that he posted. Phillip also engaged in this practice but only half as often (12 times of 88 messages). This was compounded by a technical constraint, where student communication through the CMS email system did not allow for a co-instructor to be cc’d and thus be part of the conversation. As a result, students directed their communication to Phillip, and since John was left out of the conversation it further emphasized his secondary position.

From John’s periphery position, he struggled to have a voice and to be perceived as an instructor of equal importance and value. This influenced his teaching presence considerably, since he was caught in the dilemma of simply posting to make an appearance or actually contributing something of value to the discussion.

John (interview 1): Then you think well there is also this issue if someone gets to it first, I want to avoid going on just for the appearance. Sometimes I honestly did post just to be there even though Phillip had said it well. I thought, well I need to be there, if this is a dual instructor thing—I’d better put in my two cents. Although it often didn’t seem like it mattered.

John resisted his periphery position by engaging in some counter positioning.

“[…] I felt a responsibility and I looked for my [opportunities] and tried to make contributions either big or little just to have a voice because whether they viewed me as secondary or not I thought it was my responsibility to post and make contributions where I could.”

The online context did not provide the space for John to perform or author an identity that was congruent with his well-established identity as a face-to-face instructor, and with his conceptualization of the interaction space as an online classroom. John believed that the technological constraints of the environment, in addition to the discursive practices of the co-instructor, served to position him as a secondary instructor in this teaching experience. From an activity theory perspective, John experienced tensions between the tools, division of labour, and the community components of the activity system, which in turn shaped his teaching presence.

Daniel—Community Peer or Online Classroom Instructor?

Daniel was co-teaching a Masters degree level course within a faculty of education at a Canadian university. This was his second online teaching experience, and the second time teaching the course. Daniel, conceptualized the online course as a student-centred classroom, therefore, he felt it was essential that he avoid being authoritarian, and accordingly tried to participate as a peer.

The CMS data shows that Daniel posted in 10 of the 13 weeks of the course. The majority (54) of his messages were replies to student postings. Content analysis of these postings show that 28 of 63 messages contained statements that acknowledged student contribution, while in 15 messages Daniel provided an element of his own expertise or a statement that pointed the student towards additional resources.

Daniel described the online interaction spaces as feeling like an online classroom, which is surprising since the course itself adopted relatively unconventional spaces for students and instructors to engage with, such as wikis and blogs, in addition to a series of discussion topics in a discussion forum. I had expected Daniel to suggest that this contributed to a more expanded view of an online community. Daniel elaborated on his reasons for this feeling of online classroom, highlighting that he felt pushed to take on a certain type (more traditional?) of teaching presence at the requests of his students.

Tannis (interview 1): Why would you use online classroom as opposed to, for example, a place for activities? Some [of the people I interviewed] called it a community-in-the-making. Why online classroom - is there something sort of didactic about it?

Daniel: Yes, I think because there were roles that were understood and especially early in the year there were expectations. What I found too is that if I didn’t act enough like an [authoritarian] instructor at times there were students who needed me to do that. I would see a discussion going and people would write me off line saying can you get in on this? They wanted someone to come in and lay the groundwork for it, that it was spinning out too much.

In activity theory terms, the negotiation of Daniel’s teaching presence was a result of a tension between the community, rules, and division of labour of the activity system. The expectations of the community influenced Daniel’s teaching presence to some extent, despite a constructivist approach to the design that set a competing expectation of teaching presence.

The position that Daniel preferred to adopt was one as a peer engaging in the class discussions. However, this approach had an unanticipated effect on the students’ interactions.

Daniel (interview 1): […] if the discussion was really flying along I would participate almost as a peer. Just really throwing my two cents. Actually I had to be very careful about this especially early in the classes because I started to feel like a real discussion killer. I would see this rolling, rollicking discussion with arguments and stuff flying back and forth and I would take a position as if I was a member of the student cohort and it would often stop discussion dead in its tracks, especially early on.

Tannis: Why do you think that happened? Why do you think students were thinking?

Daniel: They were perceiving me as an authority who was coming in and to disagree with me would be to risk their grade.

In fact, in one of his discussion forum postings Daniel explicitly provides a rationale for his hands off approach in the discussion.

Message no. 720[Branch from no. 645]

Posted by Daniel

Subject: Re: Ong's correlations

So many great threads -- I'm almost afraid of poking in and disrupting

the great flow you all have going[….]

The concern for creating an authoritative yet non-authoritarian presence was something that Daniel continually struggled with.

Daniel (interview 1): [ … ] especially early on in the course, I think in both instances by the end of the year there had been enough trust built up that I could kind of pitch in my two cents. I tried all sorts of things, I tried to really say that this is just my opinion but you can say those things but it takes a fairly brave student to take their teacher on.

For Daniel there were several tensions that emerged in his ability to realize this conceptualization. First, he felt that had to continually reposition himself to avoid being pulled into teacher-like discourse. Secondly, he found the constraint of the technology led him to transfer his weblog discursive practices.

“[… ] the role that was probably easiest to fill and the one that I had the most fun was not unlike how I work when I use my weblog, just finding interesting, relevant kinds of thing and then throwing them into the pot to get people talking. That was stuff that I do on my weblog all the time and had a lot of fun doing that in the forums and that was the probably the most satisfying good discussions.”

William—Knowledgeable Professor or Sage-on-the-Stage?

William had been a professor for 30 years, and was one of the early adopters of supplementing his classroom teaching with CMS discussion boards. This was his first time teaching a fully online course.

Consistent with his many years teaching as a university professor, William conceptualized his course as an online graduate seminar. Like all of the cases in this study, he subscribed to constructivist views of learning, and believed that student engagement in discussions was an essential component of this. As a distance online graduate seminar, he designed his course around a series of readings contained in a few required texts, and used the CMS uniquely as a place for student discussions. Over the course of his 4-week long intensive course, William posted 23% of all the messages. The 11 students posted a total of 1094 messages, representing 77% of the online activity. When William’s discussion forum activity is compared to that of the students, it is apparent that over the period of four weeks, he often posted a third of all the messages posted for a given day.

Table 3. William’s Discussion Forum Postings.

Total messages |

247 |

No. Initiated |

41 |

Total replies |

206 |

Both the design of the course and William’s interactions constituted a carefully calculated approach based on his own theoretical beliefs about teaching and learning. It is important to observe that William’s course adopted an unconventional design, very unlike the other distance courses in the program and at the Canadian university at which he taught. Apart from a syllabus with a schedule, and a section devoted to resources, there was no actual content created by the instructor, which was unusual for a distance course at this university.

In the interviews conducted with William, he repeatedly talked about his approach to teaching as rooted in social constructivist understandings of student learning. This understanding influenced not only how he structured and designed the online course, but also the approach that he adopted for facilitation.

William (Interview 3): I have always been a student of learning and by definition [I believe in] student-centred instruction. You have to let the students structure it so it fits in with their individual differences and their individual schema. So this pretty much influences the way I approach online instruction[…] I saw this as a potential for allowing for much more deeper reflection on the students’ part and not a simple one-way teacher-centred situation. It seemed to me an ideal technology for promoting learner-centred teaching or learner-centred learning, particularly for critical thinking—approaching material from a more profound or deeper level of processing, where there is more reflection and deeper level of thought. So this influenced my whole approach to teaching and to my online teaching.

As a way of better understanding how to direct his individualized teaching to each unique student, and as a way of developing an online community quickly, William had the students create a learning autobiography, where they reflected on and described their experiences and personal development with the course topic. William felt this was an important tool that allowed the students to position themselves as knowledgeable professionals, despite the linguistic challenges that many of them faced in communicating their expertise in an academic context.

William (Interview 2): […] I didn’t see myself as the only authority here, in fact in many of the areas they were more authoritative on aspects of Asian culture than I was and I told them so. I presented them as the authorities and each of us was an authority in certain domains.

William also believed it was essential to develop a sense of community quickly, especially in the context of a four-week intensive course. William frequently used the term “online community” in his postings, as a way of reminding students what the objective was, and what he was trying to do. He mentions the word “community” 38 times in his interactions, and often rewarded students when they demonstrated collaboration and support. The following message provides evidence of the level of transparency of his expectations.

Message no. 5636[Branch from no. 5633]

Posted by William

Subject: Re: Language and culture autobiography

[ME Student E]

Thanks for these collaborative and supportive remarks to [ME student B]. We are already on our way to developing a cooperative and understanding online community. I hope others will respond soon and this social constructivity will permeate our community. In this course we are not competing we are collaborating […]

The discussion forum transcripts show that William constantly encouraged student-student communication and avoided posting long messages. One of the strategies he used was to direct students’ attention towards the contributions of their peers.

Message no. 5779

Posted by William

Subject: Imagined communities and imaginary classes.As you can see I am very interested in this topic and I hope you will all

reply to my questions on this. Please read [ME Student C’s] response- it is

very interesting and I believe of great significance for online learning.

While students viewed William as an effective instructor, he hardly took the back seat in the discussions, and was a very active contributor. In fact, William did not view himself as a “guide on the side” nor a “sage on the stage”. Instead, the interviews revealed that a constructivist approach for William meant adopting a structure that would allow him to provide a high level of student-centred, individualized teaching. What is surprising about the frequency and amount of William’s discussion forum interactions is that students did not feel that William dominated the discussion or posted too frequently. Questionnaire data showed that students rated William highly in effectiveness of facilitation, and value of instructor contributions to the discussion. Student interviews are also enthusiastic about William’s presence.

ME Student A (interview)

Main difference of this course experience was teaching presence, when compared to other courses in the program. Structure not the defining element, but instructor presence highlights the paradox of “constructivist” courses where responsibility is on the students to learn, but doesn’t feel presence unless the instructor posts.

The significance of this case is in demonstrating that any debate about how much or little instructor interaction, or how authoritative of a position an instructor should adopt, has less to do with adhering to guidelines of ‘guide on the side’ in preference to a ‘sage on the stage’ approaches to teaching presence and more to do with the course design and structure, as determined by an instructor’s own theoretical beliefs of teaching and learning. The constraint with William’s approach was that it took a great deal of instructor time to provide individualized, intensive instruction to eleven students, yet he felt that it was worth the effort.

In an activity theory perspective, the conceptualization of the interaction space is directly related to how the instructor views the object and outcomes of the activity, or the purpose and goals of the interaction spaces (discussion forums). One of the more important findings of the study is that online discussion forums are not homogenous interaction spaces. This study demonstrated that there is considerable variation in how an instructor perceives the interaction spaces within a course and even when two interaction spaces (such as a discussion forum topic) share the same functions and objectives, there can be variation between the two instructors. For example, a discussion space for class discussion of a content-related question, a typical online course activity, engendered a very different instructor presence depending on how the instructor conceptualized this space. This is evident in the case of William who conceptualized his entire course as an online graduate seminar, and therefore attempted to simulate the type of dialogue that he would have had if it were a f2f context. As a result, William was a prolific contributor to the discussions. Daniel, on the other hand, shared William’s belief that it was important to not be perceived as an authority and attempted to reduce the instructor-student hierarchy, so as not to kill student discussion.

Both Daniel and William adopted an instructor presence that was congruent with the course design and both courses were driven by a constructivist approach to learning. But while the graduate seminar design required considerable facilitation to make it meaningful to each individual student, the design approach to the course Daniel was teaching relied on strong student-student interaction, and less on instructor-student interaction. In both cases, students had the highest average posts per week, suggesting that both instructors were successful in creating an environment that was conducive to student participation.

Implications for Teaching

This study demonstrates the need to be cautious in relying on quantifying types of interactions as a means of describing teaching presence. In some cases (demonstrated by John and Daniel) there was a disconnect between what the instructors did and what they intended to do. In the case of William, there was clear alignment with the instructor’s intentions and practices, but this only became evident in the interviews with the instructor. Having insight and understanding that there is a strong relationship between your own conceptualization of a course and how to direct your teaching is useful for instructors when tensions arise. Twiselton (2004) goes further in noting that:

The identity of student teachers, and the way this impacts on their reading of the teaching situation, structures their capacity to identify and use the opportunities for action that are available within the activity system and their identities are, in turn, shaped by these opportunities. (p. 159)

Since all teaching involves operating in systems where constraints and tensions are at play, it is important to identify resources that can assist in addressing these tensions.

Implications for Design

In distance education contexts, course design is often not carried out by the instructor who teaches the course. One of the major findings from this study was that instructors conceptualize interaction spaces differently, and this shapes their own teaching presence. Course designers should not overlook this aspect—a course designer might conceive of a discussion forum as a place for developing community through interaction, while an instructor might see it as place for focused efforts towards completing activities. Interaction spaces can take many forms, and as this study showed, the fact that two instructors can be sharing the same interaction space in the same course and conceptualize it very differently has important implications, since they might actually be engaging in different, and potentially competing practices.

The prevalence of constructivism as an underlying approach to online course design has lead to generalized views as to what a constructivist course should not only look like, but how it should be taught. The cases of William and Daniel demonstrate the considerable variance in how instructors perceive the latter. While William’s course adopted what Moore (1979, 1989) would call a “low structure” and Daniel’s course adopted a “high structure”, the design of these two courses was clearly guided by constructivist principles. Yet, despite two very different instructor approaches to facilitation and opposing degrees of structure, the students in these two courses participated (on average) the most frequently of all. This finding suggests that it is perhaps timely for both designers and instructors to begin exploring more unconventional approaches to online courses, and perhaps re-examine their views of best practices for online learning.

Implications for the COI FrameworkThere has been good effort by researchers to continue to refine and develop the COI framework, and in particular the construct of teaching presence (Shea et al, 2010; Shea, Vickers, and Hayes, 2010). In particular, teaching presence indicators, definitions, and examples such as those provided by Shea et al (2010, p. 18) provide concrete ideas for how online instructors might direct their facilitation. However, as currently conceived, the COI framework can only tell part of the story of online teaching—it provides a way of describing instructor (and student) interactions in discussion forums but is less useful in enhancing our understanding of the considerable negotiation that instructors engage in while facilitating a course. If we truly want to understand effective teaching presence, it is perhaps timely to focus on conditions and affordances that the context provides, and pay greater attention to the role of positioning, “a dynamic alternative to the more static concept of role” (van Langenhove and Harre, 1999 p. 14) and instructor identity (Twiselton, 2004) in this negotiation. This necessitates adopting a different ontological position and different theoretical and methodological approaches to investigate what remains an important construct.

The semantic value of a term such as “teaching presence” is that it provides the opportunity to go beyond notions of online teaching as facilitation: “guide on the side” or “sage on the stage”. However, the COI framework, as currently defined, limits the potential for understanding teaching presence as a much broader construct than descriptions of roles or teaching behaviours within an online context. When a sociocultural position is adopted, teaching presence could be defined as “the negotiation of instructor interactions within a mediated context with the object of attending to student learning”. Describing teaching presence as a negotiation within a mediated context requires a broader view of what instructors bring to the online context, how they position themselves and are positioned by others within it, and the components of the activity system that shape this negotiation. While COI research has been challenged to go in new directions (Garrison and Arbaugh, 2007) and a healthy debate has begun about its strengths and weaknesses (Rourke and Kanuka, 2009; Akyol et al, 2009; Jézégou, 2010), we are perhaps at a point where looking beyond the field of distance education will offer new approaches to understanding online teaching, and through the tensions of our own disciplinary activity systems, lead to transformations in our understanding.

Akyol, Z., Arbaugh, J. B., Cleveland-Innes, M., Garrison, D. R., Ice, P., Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. (January 01, 2009). A Response to the Review of the Community of Inquiry Framework. Journal of Distance Education, 23, 2, 123-135.

Anderson, T., Rourke. L., Garrison, R., Archer,W. (2001). Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 5(2), 1-17.

Basharina, O., Guardado, M., Morgan, T. (2008). Negotiating differences: Instructors’ reflections on challenges in international telecollaboration. Canadian Modern Language Review 65, (2).

Berge, Z. L. (1995). Facilitating computer conferencing: Recommendations from the field. [Electronic version]. Educational Technology, 15(1), 22-30.

Coppola, N., Hiltz, S.R. & Rotter, N. (2002). Becoming a virtual professor: Pedagogical roles and asynchronous learning networks [Electronic version]. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(4), 169-189.

Davies, B., & Harre, R. (1990). Positioning: The discursive production of selves. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 20, 43-63.

Easton, S. (2003). Clarifying the instructor’s role in online distance learning Communication Education, 52(2).

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit.

177.

Engeström, Y. (1999). Activity theory and individual and social transformation. In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen & L. Punamaaki (Eds.), Perspectives on Activity Theory (pp. 19-38). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualisation. Journal of Education and Work, 14(1).

Engeström, Y. & Miettinen, R. (1999). Introduction. In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen & R. Punamaki (Eds.), Perspectives on activity theory (pp.1-16). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y., Miettinen, R., & Punamaki, R. (Eds.). (1999). Perspectives on Activity Theory. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

Fanghanel, J. (2004). Capturing dissonance in university teacher education environments. Studies in Higher Education, 29(5), 575-590.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105.

Garrison, D. R., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2007). Researching the Community of Inquiry Framework: Review, Issues, and Future Directions. Internet and Higher Education, 10, 3, 157-172.

Harré, R., & van Langenhove, L. (1999a). The dynamics of social episodes. In R. Harré & L. van Langenhove (Eds.), Positioning theory: Moral contexts of intentional action (pp. 1-13). Oxford: Blackwell.

Harré, R., & van Langenhove, L. (Eds.). (1999b). Positioning theory: Moral contexts of intentional action. Oxford: Blackwell.

Jézégou, A. (2010). Community of Inquiry in E-learning: A Critical Analysis of the Garrison and Anderson Model. The Journal Of Distance Education / Revue De L'ÉDucation à Distance, 24(3). Retrieved November 18, 2010, from http://www.jofde.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/707 .

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, Mass: Cambridge University Press.

Linehan, C., & McCarthy, J. (2000). Positioning in practice: Understanding participation in the social world. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 30(4), 435-453.

Mason, R. (1991). Moderating educational computer conferencing. [Online]. DEOSNEWS, 1(19). (Archived as DEOSNEWS 91-00011 on LISTSERV@PSUVM.PSU.EDU).

Moore, M. G. (1973). Towards a theory of independent learning and teaching. Journal of Higher Education, 44(12), 661-679.

Moore, M. G. (1989). Three types of interaction. The American Journal of Distance Education, 3 (2), 1-6.

Morgan, T. (2008). The Negotiation of Teaching Presence in International Online Contexts. Unpublished dissertation, University of British Columbia. https://circle.ubc.ca/bitstream/handle/2429/1416/ubc_2008_fall_morgan_tannis.pdf?sequence=1

Murphy, E., & Rodriguez-Manzanares, M. A. (2009). Sage without a stage: Expanding the object of teaching in a web-based, high-school classroom. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 10, 3, 1-19.

Offir, B., Barth, I, Lev, J. & Shteinbok, A. (2003). Teacher-student interactions and learning outcomes in a distance learning environment. Internet and Higher Education, 6, 65-75.

Paulsen, M. F. (1995). Moderating Educational Computer Conferences. In Z. L. Berge and M. P. Collins (Eds.) Computer-Mediated Communication and the Online Classroom. Volume 3: Distance Learning. (pp: 81-90). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Rourke, L., Anderson, T., Garrison, D. R. & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing social presence in asynchronous text-based computer conferencing. Journal of Distance Education, 14(2).

Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. (2003). Examining social presence in online courses in relation to students' perceived learning and satisfaction. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 7(1), 68-88.

Rourke, L., Anderson, T., Garrison, D. R. & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing social presence in asynchronous text-based computer conferencing. Journal of Distance Education, 14(2).

Rourke, L., & Kanuka, H. (2009). Learning in communities of inquiry: A review of the literature. Journal of Distance Education, 23(1), 19−48.

Salmon, G. (2000). E-moderating: The key to teaching and learning online. London: Kogan Page.

Scanlon, E., & Issroff, K. (2005). Activity theory and higher education: Evaluating learning technologies. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 21(6), 430-439.

Sfard, A., & Prusak, A. (2005). Telling identities: In search of an analytic tool for investigating learning as a culturally shaped activity. Educational Researcher, 34(4), 14-22.

Shea, P., Hayes, S., Vickers, J., Gozza-Cohen, M., Uzuner, S., Mehta, R., Valchova, A., Rangan, P. (2010). A Re-Examination of the Community of Inquiry Framework: Social Network and Content Analysis. Internet and Higher Education, 13, 10-21.

Shea, P., Vickers, J., & Hayes, S. (2010). Online instructional effort measured through the lens of teaching presence in the community of inquiry framework: A re-examination of measures and approach. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 11, 3, 127-154.

Singh , G., & Richards, J.C. (2006). Teaching and Learning in the Language Teacher Education Course Room: A Critical Sociocultural Perspective. RELC Journal, 37( 2), 149-175.

Stake, R. E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 443-466). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Stake, R. E. (2006). Multiple case study analysis. New York, NY: Guilford.

Thorne, S. (2003). Artifacts and cultures-of-use in intercultural communication. Language Learning and Technology, 7(2), 38-67.

Tsang, W. K. (2004). Teacher’s personal practical knowledge and interactive decisions. Language Teaching Research, 8(2), 163-198.

Twiselton, S. (2004). The role of teacher identities in learning to teach primary literacy. Educational Review, 56(2), 157-164.

van Langenhove, L., & Harré, R. (1999). Introducing positioning theory. In R. Harré & L. van Langenhove (Eds.), Positioning theory: Moral contexts of intentional action (pp. 14-31). Oxford: Blackwell.Tannis Morgan is an Educational Technology Specialist at the JIBC where she is responsible for assisting the development and implementation of an e-learning strategy. She has a PhD in Language and Literacy Education from UBC. E-mail: tmorgan@jibc.ca