VOL. 25, No. 3

As higher education institutions progressively deliver many more courses through online mode, student retention in courses and ensuring participation in tasks and activities are becoming more a concern to teachers and educational institutions. This pilot study - an action learning project - explored the effect of including students’ identified facilitators (processes around learning organisation, tasks demands and concerns) based on the research literature on student participation in online group work and learning engagement. It was based on The Model of Teacher Action and Student Reaction in Teaching & Learning (TA-SR) that springs from The Theory of Planned Behaviour and gives consideration to what students feel and how they react to teacher decisions and actions. The result showed that such an approach to implementing online group activities has the potential to improve some students’ participation and that students may benefit by way of learning.

Alors que les établissements d’enseignement supérieur dispensent progressivement de plus en plus de cours par l’intermédiaire des systèmes en ligne, les professeurs et les établissements d’enseignement se préoccupent davantage de la rétention des étudiants et d’assurer la participation de ceux-ci à certaines tâches et activités. Cette étude pilote – un projet d’apprentissage par l’action – examine les effets découlant de l’inclusion des facilitateurs identifiés par les étudiants (processus liés à l’organisation de l’apprentissage, les exigences et préoccupations liées aux tâches) en se fondant sur la littérature scientifique portant sur la participation des étudiants au travail d’équipe en ligne ainsi que sur l’engagement envers les études. L’étude était fondée sur le modèle de l’action de l’enseignant et réaction de l’apprenant dans l’enseignement et l’apprentissage (Teacher Action and Student Reaction in Teaching & Learning ou TA-SR) qui découle de la théorie du comportement axé sur un objectif (Theory of Planned Behaviour) et prend en considération ce que ressentent les étudiants et comment ils réagissent aux décisions et actions de l’enseignant. Les résultats ont démontré qu’une telle approche à l’élaboration d’activités de groupe en ligne peut potentiellement améliorer la participation de certains étudiants et que les étudiants peuvent en tirer profit en faisant des apprentissages.

One of the principal aims of higher education learning is to ensure that students achieve meaningful learning outcomes that prepare them for the world of work, through fostering deep learning via good curriculum design and delivery. Group learning activities have been used to foster deep learning through sharing of ideas in face-to face settings. And with the explosion of online learning resulting from new technological developments, online groups have also been explored as avenues for engaging in activities that mirror interactions in face-to-face settings.

However, a substantial percentage of students do not often engage in online learning activities for reasons such as lack of time and motivation to engage; lack of skills; perceptions of the quality of the course and dissatisfaction with content; teacher support and issues with task requirements and boredom (Huett, et al., 2010; Jelfs and Richardson 2010; Roberts and McInnerney 2007; Simonson, et al., 2003). This reluctance on the part of students to participate can affect the potency of online learning activities to enhance the chances of deep learning associated with collaborative sharing of ideas, and using fellow students as help-seeking sources (Melrose and Bergeron, 2007). These issues, no doubt, have the potential to impact considerably on the quality of teaching and learning.

Higher education institutions and teachers are striving to address these issues of participation at course design levels in order to optimize student learning (Morgan, 2011).

Hrastinski (2008, p. 1761) proposed the following definition of online learner participation:

Online learner participation is a process of learning by taking part and maintaining relations with others. It is a complex process comprising doing, communicating, thinking, feeling and belonging, which occurs both online and offline. Student participation in online discussions therefore involves students’ actions such as joining and contributing ideas to the group formation process, sharing ideas with colleagues on how to execute group tasks and taking individual responsibility to complete share of group tasks.

The available research has identified the factors affecting student participation. An earlier study by Vrasidas and McIsaac (1999), which examined online interaction as perceived by teacher and students, found that interactions and, for that matter, participation, were influenced by knowledge of computer mediated communication, course structure, class-size and feedback. Vonderwell and Zachariah (2005) also identified technology and interface characteristics, student roles and instructional tasks, and information overload as some of the factors influencing student participation. More recently, researchers such as Huett, et al., (2010), Jelfs and Richardson (2010) and Roberts and McInnerney (2007) reported that participation is affected by lack of time and motivation to engage; lack of skills; perceptions of the quality of the course and dissatisfaction with content; teacher support; issues with task requirements and boredom. Cheung and Hew (2008) also named three broad categories of factors influencing participation. They include the asynchronous online discussion, role of the facilitator and design of discussion activities.

Studies have also made a range of suggestions to reduce the impact of these issues. They include up-skilling students in group processes (Daradoumis and Xhafa 2005); instilling in students the idea that the university regards such skills as important (Roberts and McInnerney 2007); implementing task and activity flexibility to address students’ lack of time (Seaman 2007; Mattes, Nanney and Coussans-Read 2003); allowing for personal choice within the learning environment to help students develop appropriate attitudes to learning and thereby increasing the chance of participation (Wlodkowski 1999); explaining the social, psychological and learning benefits of group learning, as well as the fact that such group work gives students a better chance to succeed in future work environments (since employers will be looking for people with team work skills) (Roberts and McInnerney, 2007) and ensuring instructor immediacy behaviours to minimize student dissatisfaction with content and teacher support ( Melrose and Bergeron 2007; Morgan, 2011).

All of these actions are part of what teachers can do and are known to have positive effects on online learning and learning satisfaction (Hess and Smythe 2001), and to enhance instructional effectiveness (Hutchins 2003; Woods and Baker 2004). They are also in line with Wlodkowski’s (1999) argument that the role of the teacher is to nurture the intrinsic motivation of the learner, and with Ramsden’s (2003) Third Theory of Teaching and Learning, which sees teaching as making learning possible. The ideas from “Teaching as making learning possible” encapsulate – among others – what Biggs and Moore (1993) term the motivational context of learning, including time pressures, assessment tasks, etc. and are very important because student participation is not only about how teachers set up the learning activities but in how they get students to engage in those appropriate learning activities. In short, it is about considering how students perceive learning tasks and whether or not they will engage with the required tasks. Such a consideration relates to the notion of negotiating the curriculum (Cook 1992), which promotes the fundamental idea that learning cannot be forced but is facilitated through motivation. Thus, if students are to engage in learning, then teachers need to consider the intentions and motivations of students and by extension ‘What the student does’ (Biggs 1999).

The Problem

During an offering of a semester-long course of study, the researcher observed that many students were reluctant to participate in online group activities that were part of the course. Through a search of the literature, I realized that I had fallen prey to the observation of Song and Keller (2001) that instructional designers often ignore the motivational design concerns of online learning and hope that the available technology will stimulate learner motivation. With that experience, I agreed with Huett et al. (2010) that the problem of enhancing participation in online activities is still not completely resolved and this prompted a search for ways to increase student participation in the online group learning activities in the next offering of the course.

The literature suggests that a number of issues (already discussed above,) are implicated in students’ limited engagement or non-engagement in online activities. In my opinion, there was an asymmetry in terms of teachers’ actions during course design on what they (teachers) should do and how students should respond. I thought the asymmetry betrayed that fact that, despite broad knowledge about issues affecting student participation, there is more concentration on what teachers should do and little attention paid to the exploration of what students think about learning and what they actually do to enhance their participation and learning in online activities.

Biggs and Moore (1993) highlighted this lack of attention towards what students actually do when they stated that every decision a teacher makes has a functional side (what is obvious to the teacher) and an impact side (what is obvious to the student). This raised the question of whether student participation in online group activities could be influenced in a positive way if teachers paid attention to how students perceived learning content and learning tasks in a multi-dimensional way. It also raised the question of what kind of framework could encapsulate both teacher actions and student feeling and actions (in a general way) in the teaching- learning process. Thus, it is important to focus course design, teaching, and research on what students think, feel and do in online learning environments as a way of fostering more inclination towards participation in learning activities (Kuyini 2009).

In fact, with the growing acceptance of online learning as equal alternative to face-to-face learning, it is crucial that the role of the student’s actions, attitudes and concerns regarding the teaching-learning process in online environments be explored and included in decisions about online task demands and requirements. This is to ensure that students’ participation and learning outcomes are optimized through considering all of the essential variables relating to students (as learners), teachers (as designers and instructors) and learning contexts, which are critical to good course design and to successful teaching and learning.

Aims of the Study

This pilot study–an action research project – aimed to explore an approach to organizing an online course, which included group activities using a framework (The TA-SR Model) (Kuyini, 2009) that considers the actions of teachers and students. Specifically, it aimed to investigate the effect of implementing students’ identified facilitators (processes around learning organisation, tasks demands and concerns) based on the research literature about student participation in online group work and learning engagement. It was intended as a process to improve student participation in online group activities and to foster the potential for learning engagement in the direction of a deep, rather than surface level, approach.

Theoretical Framework

Studies that have explored how to engage students in online learning have used different frameworks. For example Huett et al. (2010) used the ARCS-Based E-Mails to improve student motivation and retention. On the other hand, Duff and Quinn (2006) used Wlodkowski’s (1999) motivational framework, which strives to enhance adult motivation to learn by establishing feelings of inclusion, developing appropriate attitudes, enhancing meaning and engendering feelings of competence.

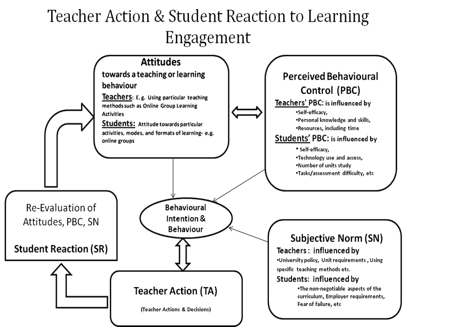

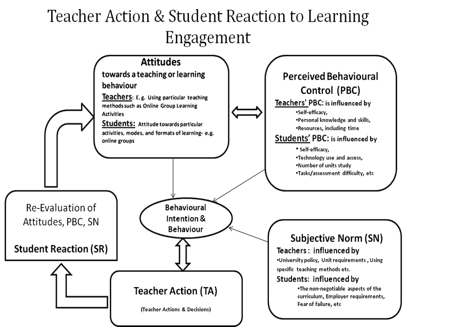

This study used The Model of Teacher Action and Student Reaction in Teaching & Learning (TA-SR) (Kuyini, 2009) as a way of encapsulating the effect of teacher decisions on what students do, including their motivation to participate in learning activities. The TA-SR model suggests that any teacher action (TA) has the effect of evoking in students a reaction (SR), whereby they re-assess their attitudes, perceived behavioural control and subjective norm. Also, subsequent changes to the task demands by the teacher would lead to a re-assessment of these elements (See Figure 2 below). This TA-SR model (Kuyini 2009) can be applied to what teachers and students do in teaching and learning as a guide for facilitating engagement and learning.

The TA-SR Model incorporates ideas from The Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1985) and Biggs and Moore’s (1993) idea about student reaction to teacher action in relation to what they termed the motivational context of learning. The motivational context of learning includes institutional demands on teachers and students, time pressures and assessment tasks.

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen 1985) holds that behavioural intention and – by extension – engaging in actual behaviour is dependent on the attitudes towards the behaviour, perceived behavioural control and subjective norm. The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) applied in the teaching-learning situation, posits that both teachers and students have Attitudes, Perceived Behavioural Control and Subjective Norms about teaching and/or learning imposed by the curriculum and contextual factors. Thus, the relationships between the teacher, student and contextual factors can be viewed within the prism of The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), where both teacher and student beliefs and actions are seen as playing crucial roles in the level of students’ participation in group activities. In other words, teacher behaviours in curriculum design and delivery create conditions for student participation and inclination towards particular learning approaches, and so do students’ own behavioural intentions and behaviour. Such interaction of attitudes and actions lead to a model of teacher action and student reaction (TA-SR) as detailed below.

Figure 1

As a way of understanding the impact of teacher decisions and actions on students, Biggs and Moore’s (1993) idea that every decision a teacher makes has a functional side (what is obvious to the teacher) and an impact side (what is obvious to the student) becomes a paramount consideration. For example, in terms of using particular teaching methods, the teacher’s decision to use online learning group activities in the current study (Teacher Action), had a functional side and an impact side. Such a decision was expected to evoke in students an assessment of their attitudes towards group participation, perceived behavioural control of engaging in such a behaviour and subjective norm in relation to compliance (Student Reaction). Additionally, other teacher actions within the unit were expected to lead to a reassessment of these positions and to influence engagement-participation.

These possible reactions were to be reasonably expected because students’ capacities to engage with online groups emanate from behavioural intention, which is mediated by attitude towards studying the particular discipline, perceived behavioural control and subjective norm. Thus, teacher actions were considered as critically important to elicit the desired reactions from students and it was, therefore, essential for the teacher to be conscious of his decisions and actions that decreased students’ motivation to engage. This is to say that all actions of the teacher needed to be assessed in terms of their capacities to enhance the behavioural intentions of students to participate (Kuyini 2009). Thus, in implementing online group activities, the initial efforts of the teacher was aimed at making activities exciting for students; building connections between what the teacher wanted students to do and their own concerns and expectations (Brookfield 1995, 93), and as a way of establishing positive attitudes towards learning tasks.

Research Questions

The following research questions were answered:

Method

This study used an action research approach. Action research describes a series of methodologies that ‘pursues the dual qualities of action and research’ (Dick, 2002, p. 159). A common element of action research methodologies is the action research spiral, where ‘thought guides action and action in turn guides thought (Dick, Stringer & Huxman, 2009, p. 6). As explained above, the study used The Model of Teacher Action and Student Reaction in Teaching & Learning (TA-SR) (Kuyini, 2009) as a way of encapsulating the effect of teacher decisions on what students do, including their motivation to participate in learning activities. Many of the research-based recommendations about how to motivate students in online activities include a collection of factors (around the learning environment) and discrete teacher actions-strategies. I wanted to use a theoretical framework that would capture the role of attitudes, perceptions of control and other compelling social factors on both the students and the teacher. As teacher-researcher, I found the Teacher Action and Student Reaction in Teaching & Learning (TA-SR) Model by Kuyini (2009) appropriate for such an explorative study. The model’s adoption of Biggs and Moore’s (1993) idea about student reaction to teacher action implied that teachers’ willingness to pay adequate attention to what should be obvious to students is a critical component of the teaching learning process.

The TASR Model captures these variables (attitudes, perceptions of control and other compelling social factors). The underlying theories of the model have been used to explore the behaviours of people in a variety of settings, including the implementation of inclusive education (Kalivoda, 1991; Kuyini & Desai, 2007; Stanovich & Jordan, 1998). It was, therefore, considered worthwhile using it to explore student-teacher behaviours in the setting up and running of online groups. The TA-SR model suggests that any teacher action (TA) has the effect of evoking in students a reaction (SR), whereby they re-assess their attitudes, perceived behavioural control and subjective norm. Also subsequent changes to the task demands by the teacher would lead to a re-assessment of these elements (See Figure 2).

Participants in the study were all students enrolled in a special education course offered online. Following the ethical approval, all students enrolled in the course were invited to complete two electronic surveys anonymously. As a participatory action-learning project, the students were told that individual learning groups could decide how to approach and organize their online group activities.

As a way of recognizing the underlying philosophy of experiential learning and in order to explore The TA-SR MODEL (Kuyini 2009) students studying in the online unit were made aware – from the outset – of their prominent role in facilitating the online group discussion activities. This was to give voice to students’ perceptions, experiences and reflections about how online group discussions should be organized, and to their learning from the process. This was done as a way of ensuring that teacher and students could have input into generating more positive attitudes, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms in the online course. In this sense their (students) actions guided my (teacher) action and my action, in turn, guided thought (Dick, Stringer & Huxman, 2009).

Instruments and Data Collection

Two sets of survey questionnaires and one open-ended question were used to collect data. The first was the Perceptions of Online Groups Survey Questionnaire and the second was the Online Groups Evaluation Survey.

The Perceptions of Online Groups Survey Questionnaire was completed by all students enrolled in the semester-long course. This three-part instrument was set in light of the three elements of the Theory of Planned Behaviour framework. The questionnaire, with Likert-type response options, contained 11 items examining students’ attitudes toward online groups (4 items); perceptions of what they felt would make it easy to participate in online groups and /or have control over their learning, representing perceived behavioural control and what factors were more likely to facilitate their compliance with unit/group demands and activities, representing Subjective Norm (7 items). Thus students’ beliefs /attitudes towards online learning and what they perceived as important facilitators of their participation in online groups in terms of three broad areas of Choice, Flexibility and Teacher Motivating Actions were measured. Wlodkowski (1999) has proposed that students need to be able to develop appropriate attitudes that have personal relevance and allow for personal choice within the learning environment (p. 133). The seven items, therefore, reflected choice and flexibility, which are the foundations of perceived behavioural control and subjective norm. The seven items were grouped into three subsets: “Student Making a Choice” (Questions 1 and 2), “Task /Activity Flexibility” (Questions 3 and 4) and “Teacher Motivating Actions/Provisions” (Questions 5, 6 & 7).

The information from these questions was needed to support teacher and student input into generating more positive attitudes, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms in the course and their groups. In line with this, students were asked to use their responses to the questionnaire as a basis for negotiating group rules and to facilitate their group activities. The teacher also used the responses to make changes or adjustments to the format and processes of the online discussion activities. The changes made to the initial discussion process included extending and spreading out submission dates for group responses; allowing each group to work out how group members who had been on practicum and joined later were to contribute to the group activities; and providing opportunity for members to comment on the score each person could earn based on their assessment of contributions to online discussions.

The other important step as part of the implementation was that students were given short information on teamwork- group processes and on the issues that make the work of online discussion groups problematic, including the free-rider problem. The explanation of the term deep learning was also provided. Students in each group were then asked to analyse, discuss and reflect on their survey responses as a basis for making decisions on how to implement their group processes. Each group was required to implement agreed upon ideas in their groups, including the kinds of things they wanted to see in the group formation process. These steps were intended to ameliorate any potential negative effects on their groups.

The general procedure was that students were given four discussion topics and were required to discuss in their groups and submit a group output for each topic. In line with the principle of instructor immediacy, the teacher was online 3 times each day for the first 3 weeks in 2-hour blocks (morning, noon and late afternoon or evening) to ensure that students’ queries were responded to promptly within 24 hours.

The Online Groups Evaluation Survey consisting of six closed questions and one open-ended question was completed at the end of the semester. It required students to reflect on their learning experiences and what they thought they had gained from the unit. The items of this survey were similar to the initial survey about perceptions to online learning; exploring students’ attitudes toward online group activities, sense of perceived behavioural control and factors facilitating their willingness to comply with unit requirements/ online group activities. The questionnaire also asked what students had achieved through studying in the unit. The one open-ended question explored student motivations (apart from wanting a good mark) for participating in the online group activities. This yielded qualitative information.

There is some debate about whether action research –as a paradigm separate from both positivist and interpretivist research – needs it owns means of establishing rigor and trustworthiness (Kemmis, 2009; Whitehead & McNiff, 2006) or if it should borrow from the social sciences (Kemmis & McTaggart, 1982). I think all research should have a flexible approach to choice of methodology but still adhere to the principle of trustworthiness of data. In order to improve the trustworthiness of the data in this study, I used a rating scale, which yielded responses that were very specific and required no other interpretation. For the one open-ended question, which provided qualitative information, specific to what motivated students to engage in the online activities, the method of establishing validity was in line with the Habermas’s criteria of social validity as put forward by Whitehead and McNiff (2006), which focus on whether or not participant responses are comprehensible, truthful sincere and appropriate. I ensured that the each response made sense (in terms of the comprehensibility criterion above). I believed that the participant responses were truthful and sincere, because respondents could not be identified by the online survey system. The responses were also appropriate because they centred on the demands of the question, which is what motivated the students to continue to engage in the online group activities. The inability to identify students for ethical reasons was a limitation, which will be discussed under limitation of the study.

A total of 150 responded to the Perceptions of Online Groups Survey Questionnaire and only 58 responded to the Online Groups Evaluation Survey. The low response rate for the second survey compared to the first can be attributed to the fact many students had little time to complete a survey at the end of the semester.

Data Analysis

In this pilot and explorative study, the scales were not subjected to reliability analysis. Descriptive statistics, which generated frequency distributions, were used to analyse the data obtained from the closed items of the two sets of questionnaire administered at the beginning and end of the semester. The open-ended question was analysed by generating themes of responses.

Descriptive statistics were used because there was no intention of finding significant differences between the pre and post responses for the following reasons:

Results

The results of this study are presented in line with the three research questions below

1. What attitudes do students hold toward online group learning?

The findings from the items focusing on whether students liked online groups; whether they felt online groups would help learning (in general) and in a deep way and whether they felt online learning gave them a sense of control over their learning showed mixed results (See details in Table 1 below).

Table 1: Student perceptions about online group learning.

Item |

Not at all

(Number & Percentage) |

Little

(Number & Percentage) |

Much

(Number & Percentage) |

Very Much

(Number & Percentage) |

Total |

| I like online groups | 29 (19%) |

64 (43%) |

47 (32%) |

9 (6%) |

149 (100%) |

| Online groups will give me a sense of control over my learning | 27 (18%) |

81 (54%) |

36 (24%) |

5 (3%) |

149 (100%) |

| Online groups will help learning in unit | 4 (3)% |

38 (26%) |

69 (46%) |

38 (26%) |

149 (100%) |

| Online groups will help learning in deep way | 5 (3%) |

52 (35%) |

68 (45%) |

24 (17%) |

149 (100%) |

The majority of the respondents liked online groups. Only 19% (n = 29) of the students said they did not like online groups at all. On whether or not online groups would give them more sense of control over their learning, 82% respondents believed that the online groups would give them some sense of control over their learning in some way. On whether they believed online groups would help their learning in the unit, 97% of students who responded said it would help in some way. Similarly, 97% of students who responded believed that the online groups would help their deep learning in some way. These responses therefore indicated that there was some positive orientation towards participating in online groups.

2. What types of teacher actions and/or arrangements are more likely to facilitate students’ participation in online group activities?

Here facilitation was taken to mean one of the following: a) give a sense of control such as in the element of Perceived Behavioural Control in The Theory of Planned Behaviour, or b) Engender a likelihood of compliance of unit demands as in the Theory of Planned Behaviour element of Subjective Norm. Students responded to questions around making a choice, task flexibility and teacher motivating actions, which includes instructor immediacy and rewards for participation. The results are presented in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Students responses on arrangements that facilitate participation in online groups.

Item Sub-sets |

Item |

Not at all No. ( % ) |

Yes

No. ( % ) |

Doesn’t Matter

No. ( % ) |

“Student Making a Choice”

(PERCEIVED BEHAVIOURAL CONTROL) |

Choosing a group gives me a sense of control over my learning | 8 (5 %) |

33 (22 %) |

108 (72 %) |

| Being placed in a group gives me a sense of control over my learning | 35 (23 %) |

19 (13%) |

95 (64%) |

|

“Task /Activity Flexibility”

(PERCEIVED BEHAVIOURAL CONTROL) |

Making the online activities flexible gives me a sense of control over my learning | 7 (5%) |

114 (76 %) |

28 (19%) |

| Giving more than a week to respond to activity/tasks gives me a sense of control over my learning | 8 (5 %) |

109 (73 %) |

32 (22 %) |

|

“Teacher Motivation Actions/Provisions”

(SUBJECTIVE NORM ) |

Equal participation is important and makes me more likely to meet unit demands | 3 (2%) |

109 (73 %) |

37(25 %) |

| Awarding scores for participation makes me more likely to meet unit demands | 11 (7 %) |

90 (60 %) |

48 (32 %) |

|

| Teacher availability makes me more likely to meet unit demands | 4 (3%) |

123 (82 %) |

22 (15%) |

In terms of the two items about “Student making a Choice”, the majority of the respondents (72%) felt that being able to choose an online group was not important. Correspondingly, 95 respondents (64%) said that it did not matter at all if they were placed in a group and only 19 (12%) preferred to be placed in a group up front. Since the majority of students did not consider choosing a group very important, the teacher did not find it necessary to change the groups.

The survey also showed that students wanted flexibility. For the majority of the students (n = 114, 77 %) making the online activities flexible was important and gave them a sense of control over their learning. Correspondingly, a total of 109 students (73 %) said that giving more than a week to respond to each group activity was important and more likely to make them comply with the demands. These responses supported the needs for flexibility and the dates for submission of group assignments were therefore adjusted from a fortnight to a month.

In terms of the teacher motivation actions, students felt that equal contributions by all members, and awarding scores for participating in the online activities were important, and, therefore, more likely to enhance their compliance with groups tasks /demands. A total of 109 (73 %) respondents said that equal participation in group work was important. Thirty seven (25%) of respondents said it did not matter, and only 3 (2%) said it was not important. Equal participation concerns are reactions towards the free-rider problem and teachers need to ensure the free-rider problem is resolved in group activities. In this vein the majority of the students (n = 90, 60 %) said that awarding scores for participating in the online activities was important and more likely to enhance their compliance with groups tasks /demands. Only 11(7 %) said that awarding scores for participating in the online activities was not important and less likely to enhance their compliance with groups tasks /demands. This finding was in line with the literature, which supports the award of group and/or individual scores for online activities.

The role of teacher immediacy in motivating participation is recognized as critical and the students’ responses to the item on teacher availability showed that the majority of them (n = 123, 82 %) felt that teacher availability on a regular basis to answer questions and respond to other concerns was important. This finding was also in line with the literature, which supports the idea, that instructor immediacy or teacher availability on a regular basis to address students’ concerns is very important in online group activities. This was an action I had already decided to implement in the unit and was confirmed by the students’ responses. On the basis of this the teacher was online at least twice a day over the first seven weeks of the program and less frequently afterwards.

3. What effect does the implementation of student ideas/views about online groups have on their participation in group activities and learning?

The implementation of the students’ views and research-based recommendations had both positive and negative effects on student participation in online groups and learning.

Firstly, the result of the Online Groups Evaluation Survey showed student attitudes toward online groups had changed in different ways (See Table 3a).

Table 3a: Students responses to the effects of participation in online group activities.

Item |

Remained Negative |

Remained Positive |

Changed to Positive |

Changed to Negative |

| The unit’s activities changed my attitudes towards Online group work | 11 (19 %) |

24 (41%) |

13 (22%) |

10 (17 %) |

Eleven of the 58 respondents (18.9 %) said that their attitude towards online learning remained negative, with 24 (41%) reporting that their attitudes remained positive. At the time 13 students (22%) students reported that their attitudes had changed for the positive after participating in this unit. On the other hand, the attitudes of 10 (17%) students with positive attitudes changed to the negative. Thus, students’ learning experiences in the online groups created changes in their attitudes in different ways. Although the implementation of students’ ideas was in line with Cook’s (1992) notion of negotiating the curriculum and an attempt to minimize the extent to which students’ dislike for particular aspects could influence their reactions and engagements with those aspects of a course, the effect was minimally positive. For those whose attitudes changed for the negative, it might be the result of specific aspects of the organization of the online program that may have been unpleasant, which underscores the role of teacher actions in students’ experiences.

The other items of this survey examined students’ perceptions of the effects of the online groups on their learning and sense of control. Table 3b below contains the findings.

Table 3b: Students responses to the effects of participation in online group activities.

Item |

Not at all Number & Percentage) |

Little Number & Percentage) |

Much Number & Percentage) |

Very Much Number & Percentage) |

| Online group gave me a sense of control over learning | 10 (17 %) |

32 (55%) |

14 (24%) |

2 (3%) |

| Online groups helped my learning in unit | 6 (10%) |

27 (47%) |

15 (26 %) |

10 (17%) |

| Online groups helped my learning in a deep way | 13 (22%) |

22 (38 %) |

16 (28%) |

7 (12%) |

| Teacher availability and support contributed to my participation | 11 (19 %) |

16 (27.5%) |

19 (33%) |

12 (21%) |

| Flexibility of online group activities contributed to my participation | 6 (10 %) |

22 (38%) |

21 (36%) |

9 (16%) |

| The award of scores for participation contributed to my participation |

15 (26 %) |

17 (29%) |

12 (21 %) |

14 (24%) |

*Making a choice of groups was not measured because the initial survey found that is was not important

Table 3b(2)

Paired Samples Statistics |

|||||

Mean |

N |

Std. Deviation |

Std. Error Mean |

||

| Pair 1 | Pre Course Attitude Towards Online groups | 1.60 |

58 |

.493 |

.065 |

| Post Course Attitude Towards Online Groups | 1.64 |

58 |

.485 |

.064 |

|

Paired Samples Test

|

|||||||||

Paired Differences |

|||||||||

95% Confidence Interval of the Difference |

|||||||||

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Std. Error Mean |

Lower |

Upper |

t |

df |

Sig. (2 tailed) |

||

Pair 1 |

Pre Course Attitude Towards Online groups | -.034 |

.620 |

.081 |

-.198 |

.129 |

-.423 | 57 | .674 |

| Post Course Attitude Towards Online Groups | |||||||||

Although only 27% of respondents said that the way the online groups were organized gave some sense of control over their learning, 10 students (17%) reported that the online groups did not give them a sense of control over their learning. And 55% (n = 32) said that it gave them little control over their learning. The results above indicate that participation in the online groups was satisfying for a quarter of the students and that the arrangements, processes and adjustments implemented had some positive effect on participation. The finding that majority of respondents (72%) felt that the online groups did not give them a sense of control over their learning, indicates that perhaps the group activities constituted an unwelcome distraction to the way many students wanted to engage with the unit. The group activities were compulsory and, therefore, part of those non-negotiable aspects of the course. Students therefore participated because it was a requirement; otherwise it was something they would rather do without. The challenge for the teacher is find ways to ensure that students see the online group activity as something that enhances their learning.

With respect to online group activities helping student learning, 43% (n = 25) reported that the online groups helped their learning in the unit. Another 47% said that it helped them only in a minimal way and 10% reported that it did not help them at all. Similarly only 40% reported that online groups helped their learning in a deep way. The rest (60%) believed that the online groups did not help their learning in a deep way.

However, in terms of teacher influence on student participation, 53% of the respondents said that teacher availability to answer questions contributed to their participation and this is indicative of the importance of teacher availability to the students’ continued participation. More than 50% of the respondents said that the flexible nature of the online group activities contributed to their continued participation in the unit.

The responses about the role of rewards or scores in participation were mixed, however. Although the majority reported that it helped their participation, a substantial percentage (26%) said it did not help at all. Also, 29% reported that its role was “little” or minimal. These two responses collectively indicate that the role of rewards was not that big. This is surprising but can be attributed to weight of the reward. The online group activities accounted for only 10% of the total score and two students who decided to withdraw from the unit said that the work was too much for 10%.

Further, the responses to the open-ended question were examined to explore the main student motivations (apart from wanting a good mark) for participating in the online group activities. The findings showed that the main reasons students want to participate in the online discussion groups were:

a) Knowledge/skills/ competencies /other information

b) Communication/interaction/ collaboration

c) Flexibility

d) Reduction in isolation,

e) Support from the teacher,

f) Interesting learning tasks

In terms of knowledge/skills/competencies and other information, the students’ responses revealed that students believed that the group discussions would help them gain knowledge of the theories and different approaches to behaviour management as well as skills in group-work. For some students, the group discussions helped them understand the potential challenges of teams of teachers working together to deal with problematic student behaviour in school settings. In relation to this, one respondent said:

“(To have) An understanding of the different approaches to behaviour management, and a firm conviction of the kind of approach I wish to adopt. Working with groups to get an outcome when none looked unlikely ….and also I learnt from this group that I will encounter many teachers with different opinions as I did students within this unit”.

In terms of communication/interaction/ collaboration, the student responses showed that students believed that the discussions would afford them the opportunity to improve their skills in online communication, in dealing with other people, and in making connections with others/ minimiszing the isolation of distance and collaboratively sharing of ideas. One of the students said it made it easy to have “Connection with other students”. She also noted “The fact that others have strengths in areas you do not and often you have strengths in areas they do not and many external students are often older students and they bring a wealth of experience to the table. I was able to discuss questions within a group regardless if my answer was right or wrong”. Another student said it provided opportunity for interaction, so that one does “not feeling like you are alone”.

In terms of flexibility, the students’ comments below mirror the quantitative responses in Table 3b and buttress relevance of flexibility to student participation. In fact, extending the timelines for group responses and allowing for groups to decide how to approach activities support student continued participation. Some student comments follow:

“It was very flexible regarding when we could post our messages and generally another group member would comment or answer back giving a good sense of communication”

“Everybody is really supportive and there are no dramas if group members don't have the right answer. They are flexible and everyone is willing to help. We didn't have to answer questions immediately; from the time the question went up we had about 2 weeks to answer. Some groups I have been in at uni have been grouped according to specialist subject (i.e. all history teachers grouped together) and I don't think this enabled a really varied range of opinions and ideas to be expressed”

“The flexibility to provide input at the most available time for yourself and not rely on having everyone "in the same room" at the same time”.

Discussions and Reflections

The findings of this study have been interpreted with caution because it is an explorative study and limited to online group activities only. Therefore, the findings cannot be generalized beyond aspects of online course design that relate to online group activities. However, the model and the findings may be useful for designing online group activities where teachers are looking to increase students’ motivation to participate in group tasks.

The results showed that implementing online group activities with the framework of the Theory of Planned Behaviour and the TA-SR MODEL (Kuyini 2009) in mind could be useful in maintaining students’ motivation to participate. The survey data showed that there were some positives and students reported that the online groups helped their learning in the unit. Nonetheless, some five students still withdrew from the unit, for reasons related to the online group activity. However, three of the five students changed their minds and decided to continue after the adjustment in timeframe for submission of group outputs, which reflected the responses from the initial student survey.

This outcome, along with the results of the survey in which student expressed desire for flexibility, indicate that flexible demands (also recommended by Wlodkowski (1999) are important in enhancing participation in online group activities. It also supports the ideas embedded in the theoretical framework of the study, which holds that teacher actions can lead students to re-evaluate behavioural intentions - through reassessing their attitudes, perceived behavioural control and subjective norms. Secondly, embracing the principle of instructor immediacy (Melrose and Bergeron 2007) and being available online - as a way of creating positive attitudes towards participation and enhancing the creation of a subjective norm for student engagement- proved useful, with students reporting that such actions facilitated their learning and contributed to their continued participation.

The evaluation responses tied in well with the initial survey, where students appreciated instructor immediacy. This kind of support is especially noteworthy because it allowed the online groups to navigate the different stages of learning groups and to get through the critical stage of ‘Norming’ which Tuckman, (1965, 1977) says is characterized by attempts to resolve earlier conflicts, and set clear expectations of behaviours and roles. Indeed, getting the groups through the stage of ‘Norming’ actually created a fertile condition for each individual student to develop a good subjective norm (the third variable in the Theory of Planned Behaviour), for participation in the online groups. Reaching this stage was important because it is a stage beyond which Tuckman (1965, 1977) suggests that groups concentrate on performing. Many students expressed satisfaction with this teacher presence. One student wrote: “… I consider the unit itself well run and clear in its intentions and requirements…..the assignments (including the group work) were well designed to achieve a deep knowledge of the subject matter….. The lecturer was very helpful”.

The introduction of a reward system improved students’ participation, but only minimally. This was due to the disproportionate nature of the work required to the score (10% of total mark) to be earned. This indicates that serious consideration should be given to providing adequate reward for the group tasks. This is because it is a way of creating a kind of successive approximation to the ultimate consequence, and fits in with Maag’s (2004) argument that student behaviour is motivated more by immediate rather than long-term consequences and unless we find ways of meeting these needs, not all students will be motivated to participate in these online groups. On the other hand, teachers need to be aware of the danger or possibility that some students may approach group learning at a surface level because their participation is anchored to the scores or the fear of failure, which is known to be associated with surface learning (Ramsden 1992). Nonetheless, some reported that online activities helped their learning, as they gained some competencies, and provides grounds for teachers to continue to use such activities.

Limitations of Using the Approach

The main methodological limitation was around student identification. The researcher had asked students to put a unique code on top of their responses. Since there was a superordinate-subordinate relationship between the research and the students, the use of unique codes was to avoid contravening ethical principles around the researcher’s power over respondents. It is common knowledge that such a relationship can influence student’s responses, whereby they simply give “grateful testimonials” in order to please the teacher. Some students did not add a unique code to their sheets and this created a problem with comparing results of the pre and post course survey data.

The other limitations were the timing of the surveys, student participation in the surveys, workload for the teacher and the students and systemic issues around technology.

The timing of the survey and the group preparations were hindrances to positive experiences. Many groups were under pressure to complete their group processes in time to start online tasks, and this dampened spirits in some students. This outcome suggests that in order to be successful with the approach used in this investigation, the group processes need to be given more time and perhaps start at least a week before the actual semester work begins.

The number of students responding to the final survey was rather small (58 compared to 149 for the initial survey). This was not ideal and undoubtedly affected the conclusions that could be reached overall.

This action-learning project has sought to explore the facilitators and barriers to student participation in online group learning and to examine the effects of implementing student views, ideas and concerns on student participation and learning.

The findings showed that using the Theory of Planned Behaviour Framework and the TA-SR Model, which adhere to the notion that teacher and students actions are all critical to learning, might be useful. It allows a consideration of what students feel and how they react to teacher decisions and actions and to adjust task demands to facilitate participation. The study found that students’ participation in online group activities has a chance to improve by this method and that some students do benefit by way of learning, including a deep approach through the use of online groups. The study unearths and supports the idea that systemic issues, such as timing of activities should always be considered when using online groups.

Ahmed Bawa Kuyini is a lecturer in Education and Social Work at the University of New England, Australia. E-mail: kuyinia@une.edu.au