VOL. 26, No. 1

The objective of this study was to describe the extent to which students in a limited-residency doctoral program are immersed in an environment that engenders academic socialization. We surveyed students in a doctoral program offered by a faculty of nursing in which the on-campus residency requirement is limited to four weeks, and collected data with Weidman and Stein's (2003) Doctoral Student Socialization Questionnaire. Of the 54 students enrolled in the program, 37 responded to our survey. Activities associated with four of the six dimensions of academic socialization were prevalent (student-student interaction, scholarly encouragement, department collegiality, and supportive environment); two sets of activities were not prevalent (participation in scholarly activities, and student-faculty interaction). Our results provide an empirical, theory-based exploration of the assumption that the environment of limited-residency doctoral programs are necessarily impoverished. The model and instrument pinpoint specific issues for program administrators to address.

Cette étude visait à décrire dans quelle mesure les étudiants participant à un programme doctoral d’apprentissage combiné sont immergés dans un environnement qui engendre la socialisation scolaire. Nous avons questionné des étudiants participant à un programme du doctorat offert par la faculté des sciences infirmières qui exigeait une présence en classe limitée à quatre semaines et nous avons recueilli les données à l’aide du Questionnaire de socialisation des étudiants aux études de doctorat élaboré par Weidman et Stein (2003). Parmi les 54 étudiants inscrits au programme, 37 ont répondu à notre sondage. Des activités liées à quatre des six dimensions de la socialisation étaient très répandues (l’interaction d’étudiant à étudiant, l’encouragement à l’érudition, la collégialité départementale et un milieu propice à l’apprentissage); alors que deux séries d’activités étaient peu répandues (la participation à des activités savantes et l’interaction étudiant-professeur). Nos résultats fournissent une exploration empirique, fondée sur la théorie, de la supposition voulant que l’environnement d’un programme doctoral d’apprentissage combiné doive nécessairement être plus pauvre. Le modèle et l’instrument utilisés identifient des questions précises que les gestionnaires de programmes peuvent aborder.

Doctoral programs with one- or two-year residency requirements are unwelcoming to those working in the professions, including nurses, many of whom are reluctant to suspend their careers or relocate their families to be on a university campus for an extended period of time. This contributes to the chronic shortage of doctoral-prepared nurses and the cascade of ensuing problems (Canadian Nursing Association, 2008).

Limited-residency doctoral programs; sometimes called online, blended, or distance programs; are a potential solution. Harnessing advances in learning theory and in information and communication technologies, these programs reduce residency requirements substantially and embody the ethos of open learning.

However, as a few institutions begin to offer limited-residency doctoral programs another problem surfaces. Many stakeholders—including senior faculty, potential students, and accreditation agencies—express skepticism about the ability of such programs to achieve the distinct objectives of doctoral education (Adams & DeFleur, 2005; Confessore, 1999; Flowers & Baltzer, 2006; Klinger, 2007; Montell, 2003; Moore, 2005). Because students are not by definition taking up residence in an academic milieu they cannot encounter and thereby appropriate the values, norms, and tacit knowledge required to successfully assume their post-graduation roles of researcher, instructor, student advisor, or administrator.

The purpose of this study is to describe the extent to which students in a limited-residency doctoral program are immersed in an academic milieu.

For half a century, researchers have used the construct socialization to organize studies of learning as it occurs through immersion in distinctive environments. The influential American sociologist Robert Merton and his colleagues conducted a germinal study on this topic with student-physicians, and they defined the object of their investigation as “the process through which people selectively acquire the values and attitudes; the interests, skills, and knowledge—in short, the culture—current in the groups of which they are, or seek to become, a member” (Merton, Reader, & Kendall, 1957, p. 287).

Academic Socialization

The derivative construct academic socialization emerges from the large body of research into the processes through which graduate students acquire the values, skills, and tacit knowledge current in the academic community (Gardner & Mendoza, 2010). Several authors have contributed to the specification of these qualities, (Anderson, Ronning, & DeVries, 2010; Becher & Trowler, 2009; Braxton, 2010; Carter, 2008; Kopelman, Prottas, & Tatum, 2004; Tschannen-Moran & Nestor-Baker, 2004) and several others have provided conceptual and empirical discussions of the process through which they are transmitted to doctoral students (Austin Campa, Pfund, Gillian-Daniel, & Mathieuet al., 2009; Gardner, 2007; 2008; 2010; Golde, 2000; Hadet, Hatem, Fecile, Stein & Haley, 2008; Hakala, 2009; Kirk & Todd-Mancillas, 1991; Jazvak-Martek, 2009; McCarty & Hirata, 2010; Mendoza, 2007; Morita, 2009; Ondrack, 1975; Pavalko & Holley, 1974; Pease, 1967; Rosen & Bates, 1967; Rosser, 2004; Saks, Uggerslev & Fassina, 2007; Schein, 1967; Sweitzer, 2009; Toombs, 1977).

Weidman and Stein have synthesized much of this work and developed one of the few models of the academic socialization process. This has lead to the development of data collection instruments and empirical studies (Stein & Weidman, 1989; Weidman & Stein, 2003; Weidman, Twale, & Stein, 2001). As operationalized in their questionnaire, academic socialization is comprised of six dimensions, which are listed in Table 1 along with some representative items that elucidate their meaning.

Table 1. Processes of academic socialization as represented in Weidman and Stein’s questionnaire

| Process | Representative Items |

| Participating in scholarly activities | Writing, alone or with others, papers submitted for publication

Contacting scholars at other institutions to exchange views on scholarly work |

| Student-faculty interaction | Engaging in social conversation with faculty members Discussing, with faculty members, topics in their field |

| Student-student interaction | Discussing, with other students, topics of intellectual interest Talking with others students about personal matters |

| Supportive faculty environment | Faculty are accessible for scholarly discussions outside of class Offering enrichment activities (seminars, colloquia, social events) |

| Department collegiality | Faculty treating students as colleagues Faculty regarding students as serious scholars |

| Student scholarly encouragement | Promoting long-lasting friendships and associations among students Providing sufficient opportunities for students to participate in the scholarly activities of faculty |

Limited-residency Doctoral Programs

A vast body of literature informs Weidman and Stein’s model, but it comes entirely from explorations of traditional doctoral programs in which the typical residency requirement is two years. No studies have investigated the socialization process in limited-residency doctoral programs, a term that refers to programs in which students are required to meet on campus for only brief periods of time with the bulk of their education conducted through asynchronous and synchronous web-based tools (Terrell, 2005; 2002). Normatively, the term limited is coming to mean one to two weeks of residency for each year in a doctoral program. Thus, a student completing a doctoral program in four years would spend a total of only four to eight weeks on campus.

The empirical study of limited-residency doctoral programs is sparse, and claims arising from the existing studies prompt questions of trustworthiness or validity. Most studies: i) do not build on each other or on theory ii) most studies present data collected with locally-developed instruments with unknown psychometric properties, iii) use convenience, volunteer sampling strategies, iv) are conducted by program personnel, and v) employ descriptive research designs. With these characteristics, it is difficult to extend the results beyond the settings in which they are conducted. Topics of study include participant satisfaction, student characteristics, attrition, perceived learning, and referencing style in dissertations (Banks, Joyes, & Wellington, 2008; Bettman, Thompson, Padykula & Berzoff, 2009; Brahme & Walters, 2010; Klinger, 2007; Lim, Dannels, & Watkins, 2008; Reynolds, 2010; Schoech, 2000; Terrell, 2005; Terrell, Snyder & Dringus, 2009; Thompson & Allen, 2010; Tunon & Brydges, 2009; Wikeley & Muschamp, 2004).

Two of the issues in these studies of limited-residency doctoral programs are relevant to academic socialization: student-to-faculty and student-to-student interaction (both formal and informal), which are two of the six factors in the Weidman and Stein model. As a measure of this interaction, the Doctoral Student Connectedness Scale is under development and initial administrations find little connectedness between limited-residency doctoral students and their faculty, and even lower levels of connectedness among the students. Reports of isolation, loneliness, and disconnection appear throughout the literature (Banks et al., 2008; Brahme & Walters, 2010; Lim et al., 2008; Thompson & Allen, 2010).

The extent to which students in limited-residency doctoral programs engage in these and the other four processes that Weidman and Stein associate with academic socialization is an open question. The purpose of this study is to describe the extent to which students in a limited-residency doctoral program engage in, and are surrounded by others engaging in, activities associated with academic socialization.

Research Design

To field this question, we employed a descriptive design in which we collected data that would allow us to characterize the extent to which students are immersed in an academic environment. We chose a descriptive design rather than a comparative or quasi-experimental design because it was not possible to locate sets, or even two, doctoral programs that were similar in all parameters except the explanatory variable, i.e., residency requirements (limited-residency versus full-residency). Moreover, our case was selected using a nonprobability sampling strategy. We did so because the population of limited-residency doctoral programs, at this point in time, is small.

Participants

The participants in our study were recruited from a limited-residency doctoral program offered by a faculty of nursing. The program has been operating for ten years and offers PhD degrees and Doctorate of Nursing Practice degrees. The residency requirement is one week per year during the two to four years it takes students to complete their coursework. Currently, 57 students are enrolled in the programs and, of these, 37 who were at various stages of their programs, responded to an invitation to participate in our study.

Data Collection and Analysis

To collect data from the participants we used the Doctoral Student Socialization Questionnaire developed by Weidman and Stein (2003), which, as we described, is comprised of 34 Likert-style items organized into 6 subscales. Weidman and Stein report internal reliability coefficients for each of the subscales ranging from a low of .64 for student-faculty interaction to a high of .81 for student-student interaction.

In this exploratory study, our goal was to describe the academic environment in which the students are immersed. We do so by reporting percentages of participants across the response categories for each of the 34 items of the questionnaire.

We conducted internal consistency reliability tests on our data, and produced the following coefficients for each of the six subscales: Participation in scholarly activities (α = .77), student-faculty interaction (α =.64), student-student interaction (α =.81), supportive faculty environment (α =.81), department collegiality (α =.71), student-scholarly encouragement (α =.80).

The results are grouped by the six dimensions of academic socialization, represented in Weidman and Stein’s (2003) questionnaire.

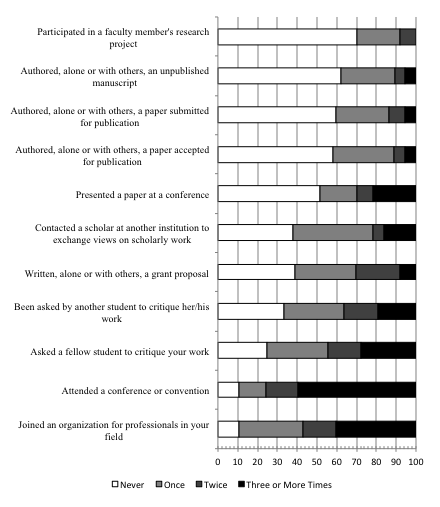

Figures one presents the students’ responses to the 11 items comprising participation in scholarly activities. Less than half of the students have ever participated in a faculty member’s research project, authored a manuscript (published or not), or presented at a conference. Students were more likely to participate often in less demanding scholarly activities, such as attending a conference or joining a professional organization. (See figure 1).

Figure 1: Participation in scholarly activities in a limited-residency doctoral program (n = 37)

During your doctoral degree, how often have you:

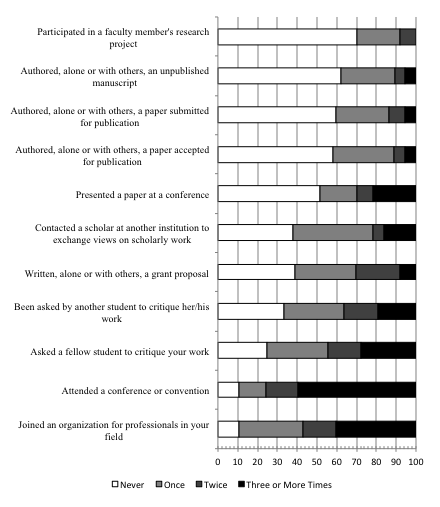

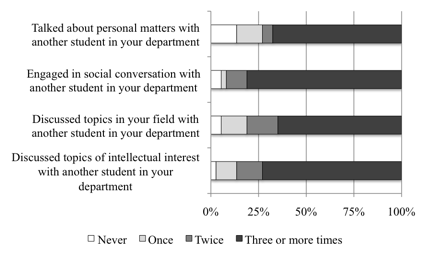

Figure two presents the students’ responses to the four items comprising student-to-faculty interaction. Many of the students engaged in social conversation with faculty members but far fewer went any deeper to discuss topics in their field or talk about personal matters. (See figure two).

Figure 2: Student-to-faculty interaction in a limited-residency doctoral program (n = 37)

As a doctoral student, how often have you:

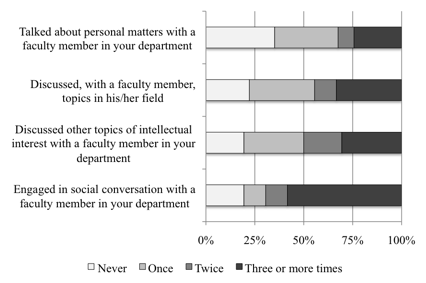

Figure three presents the students’ responses to the four items that comprise student-to-student interaction. The students were much more likely to interact frequently with other students than they were with faculty members. (See figure 3).

Figure 3: Student-to-student interaction in a limited-residency doctoral program (n = 37)

As a doctoral student, how often have you:

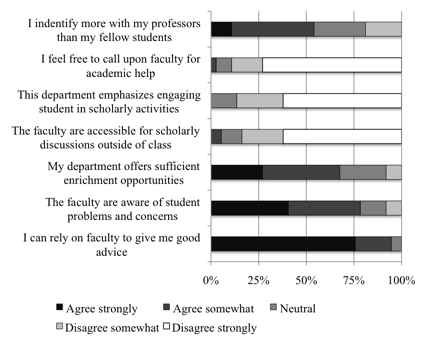

Figure four presents the students’ responses to the seven items comprising supportive faculty environment. Consistent with the finding that few students went beyond social conversations with their instructors, most did not agree that faculty members were available for help, engaged them in scholarly activities, or were accessible outside of class. (See figure four).

Figure 4: Supportive faculty environment in a limited-residency doctoral program (n = 37)

For each of the following, indicate the response that best reflects your level of agreement:

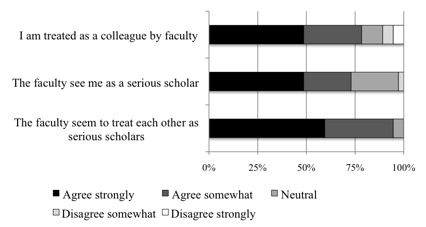

Figure five presents the students responses to the three items comprising department collegiality. Students were split on their sense of whether they were treated as colleagues, whether they were regarded as serious scholars, and whether the faculty treated each other as scholars. (See figure five).

Figure 5: Department collegiality in a limited-residency doctoral program (n = 37)

For each of the following items, indicate the response that best reflects your level of agreement:

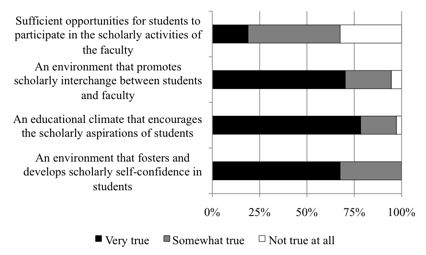

Figure six presents the students’ responses to the four items representing scholarly encouragement. A majority of students had a favorable impression of their program’s ability to nurture their self-confidence and aspirations, and, as they reported elsewhere, student-to-student interaction. (See figure 6).

Figure 6: Student scholarly encouragement in a limited-residency doctoral program (n = 37)

The following is a list of various advantages and disadvantages of academic departments. Please indicate how true each one is in your department:

The purpose of this study was to describe the extent to which students in a limited-residency doctoral program are immersed in an environment that will support academic socialization. The students described an environment rich in some, but not all, of the attributes featured in Weidman and Stein’s model. Student-to-student interaction, scholarly encouragement, department collegiality, and support were prominent features of their environment; participation in scholarly activities and student-to-faculty interaction were not.

The first four aspects are linked with socialization in numerous studies of full-residency doctoral programs (Hakala, 2009; Gopaul, 2011). In limited-residency programs, data has been collected primarily on student-to-student interaction, and using this metric our respondents appear advantaged. Existing reports of limited-residency programs find interaction to be so infrequent that it is implicated in a) abnormally high rates of attrition (Terrell et al., 2009), b) persistent feelings of loneliness, isolation, and levels of estrangement that render students unlikely to turn to other students for support of any type (Brahme & Walters, 2010); and c) unsuccessful attempts to address these problems with information and communication technologies (Banks et al., 2008; Lim et al., 2008). Overall, our participants’ characterization of their environment concerning these dimensions is encouraging.

Their characterizations of the remaining two dimensions—student-to-faculty interaction and participation in scholarly activities—is less encouraging. Empirical studies support the intuitive assertion that interaction between doctoral students and faculty members is an irreplaceable aspect of academic socialization. In part, this is deductive. Early theories of socialization reserved a prominent place for socialization agents—the entities who carry out socialization. In the germinal study on the socialization of student-physicians, the authors found that “socialization takes place primarily through interaction with people who are significant for the individual—in the medical school, probably with faculty members above most others” (Merton et al., p.41, 1957). This finding continued to receive support over the ensuing five decades. Focusing exclusively on its impact on academic socialization, research has linked interaction between doctoral students and faculty with i) the internalization of the norms, values, and/or attitudes of faculty members (Braxton, Lambert & Clark, 1995; Schein, 1967); scientists (Anderson & Louis, 1994; Braxton, 1991; Mendoza, 2007); and productive researchers (Corcoran & Clark, 1984), ii) the development of a scholarly self-image (Kirk & Todd- Todd-Mancillas, 1991) , iii) the acquisition of accurate images of the faculty life (Gardner, 2007), iv) an increase in commitment to the academic profession (Gottlieb, 1961), vii) socialization to the scholar’s role (Weidman & Stein, 2003), viii) and frequency of participation in professional activities (Pease, 1967; Weiss, 1977).

Perhaps even more impactful than student-to-faculty interaction, however, or the four dimensions discussed previously, is participation in scholarly activities. Weidman, Twale and Stein (2001) argue that “involvement is the activity by which novices acquire and internalize an occupational identity, develop an interest in a profession’s problems, and take pride in perfecting technical skills.” Involvement with faculty members and senior doctoral students gives students insights into professional ideology, motives, and attitudes. Much of the data collected in full-residency doctoral programs is supportive of this argument. Results indicate that student-physicians who have multiple dealings with patients, student-musicians who join the musicians’ union and get gigs, and doctoral students who work as teaching or research assistants are more likely to regard themselves, respectively, as doctors, musicians, and scholars than their counterparts (Austin, 2002; Becker & Carper, 1956; Helland, 2010; Huang, 2009; Kadushin, 1969; Merton et al., 1957; Parry, 2006; Pitkayla & Mantyranta, 2003).

Infrequent participation in scholarly activities or student-to-faculty interaction is not necessarily an artifact of the limited-residency in the doctoral program we studied. The prevalence of these processes in two traditional, full-residency doctoral programs (one in Sociology and one in Education) has been assessed using the same data collection instrument we used. For all but two items students in the full-residency programs were engaged less frequently than those we studied in each of the activities that contribute to academic socialization. This comparison provides some evidence that contradicts the categorical assumption that the environment of limited-residency doctoral programs is necessarily impoverished.

There are limitations to our conclusions. Our design is a description of one case, and we selected a case that was convenient. Our data do not support general conclusions about limited-residency programs or about their efficacy in comparison to full-residency programs. The number of limited-residency doctoral programs (i.e., the population) is small and heterogeneous, making it difficult to conduct control trials in which participants are sampled randomly and all program variables are constant except the residency requirement. Because limited-residency doctoral programs are a new phenomenon in the health sciences, many of the elements of conclusive research are not yet in place (e.g., large populations, psychometrically-sound instrumentation, an existing literature). Nevertheless, it is necessary to take the first steps in a research program on this important issue.

The study provides some direction for subsequent practice and research. The model of academic socialization that framed our study and its operationalization in the survey instrument can help program developers move beyond ideological arguments for or against limited-residency programs to address specific educational issues. For instance, students in the program we examined need more opportunities and encouragement to engage in the real work of professional scholars if they are to acquire the tacit knowledge, values, and norms possessed by successful academics. This includes work such as writing grant proposals, conducting research, authoring reports, and submitting manuscripts to journals. Subsequent investigations could advance this research program with examinations of the psychometric properties of the Doctoral Student Socialization questionnaire. Weidman and Stein (2003) present some data concerning its reliability, but much work remains. Further, case studies that offer in-depth, holistic pictures of academic socialization in limited-residency programs will be more valuable that one-dimensional survey studies; and comparative case studies that juxtapose limited- with full-residency doctoral programs will offer much insight.

In this study we did not argue that there is something pedagogically magical about propinquity that cannot be recreated with information and communication technologies. Nor did we argue that limited-residency programs are an inevitable evolution from traditional doctoral programs. We have instead identified a coherent and established set of educational constructs with which to consider, empirically and theoretically, the gains and losses associated with limited-residency doctoral programs.

Liam Rourke is the Director, Educational Scholarship and Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry, University of Alberta. E-mail: liam.rourke@gmail.com

Heather Kanuka is a Professor and Academic Director, Centre for Teaching and Learning in the Faculty of Education at the University of Alberta. E-mail: heather.kanuka@ualberta.ca