VOL. 26, No. 2

This paper discusses students’ experiences with the use of identification codes in a graduate course delivered asynchronously via the Internet. While teaching an introductory masters level graduate course in distance learning, the authors discovered that the learning management system, Moodle, was programmed to display identification codes rather than student names when in the Student View mode. Consequently, when students participated in Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) text discussions, their posts were attributed to their computer-generated IDs. Investigation into the identification protocol revealed that the institution had adopted a policy of using identification codes to comply with Alberta’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy (FOIP) Act. We wondered what it meant to graduate students to be identified by a computer-generated code rather than by name. In the context of an asynchronous CMC discussion forum, we asked how the use of an identification code affected students’ sense of identity within the online learning environment. Analysis of their responses revealed categories relating to personal identity (depersonalization and anonymity), social identity (community, learning, and engagement), and questions concerning suitable names for identification purposes. Most learners felt strongly that they should not be known through a numeric code and that their name was more personable.

Cette étude traite d’expériences vécues par des étudiants qui ont utilisé des codes d’identification dans un cours d’études supérieures donné de façon asynchrone par l’intermédiaire d’Internet. C’est en donnant un cours d’introduction en matière d’éducation à distance au niveau de la maîtrise que les auteurs ont découvert que le système de gestion de l’apprentissage, Moodle, était programmé pour afficher les codes d’identification plutôt que les noms d’étudiants lorsqu’on était en mode "Student View". Par conséquent, lorsque les étudiants participaient à une discussion de texte par voie de communication électronique, leurs postes étaient attribués à leurs identifiants générés par ordinateur. Une enquête sur le protocole d’identification a révélé que l’établissement avait adopté l’utilisation des codes d’identification pour se conformer à la loi sur l’accès à l’information et la protection des renseignements personnels (Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy (FOIP) Act) de l’Alberta. Nous nous sommes demandé ce que cela pouvait représenter pour les étudiants d’études supérieures d’être identifiés par un code généré électroniquement, plutôt que par leur nom. Dans le contexte d’un forum de discussion asynchrone par ordinateur, nous leur avons demandé comment l’utilisation d’un code d’identité les influençait au niveau de leur sentiment d’identité dans le cadre de l’environnement d’apprentissage en ligne. L’analyse de leurs réponses a révélé diverses catégories en lien avec l’identité personnelle (dépersonnalisation et anonymat), l’identité sociale (communauté, apprentissage et implication), ainsi que des questions relatives à quels noms pourraient convenir à des fins d’identification. La plupart des étudiants étaient fortement d’avis qu’ils ne devraient pas être identifiés par un code numérique et que leur nom était un mode d’identification beaucoup plus sympathique.

There are times when my voice as a student feels so small and isolated as I try to make posts and engage with other learners who seem so far away. So if I am Horton listening for all the little voices of my fellow students out there, or if I am a Who trying to have my voice heard, the effort is worth it because I am learning. – LaraCe3

Unprecedented access to information is transforming and defining our society in the 21st century. At stake is our individual privacy. A little sleuthing on the Internet can reveal preposterous amounts of information about individuals. Some of the information is volunteered through social media sites and personal web pages, but other information may be disclosed without the consent of the individual. Electronic databases of personal and private information can be disclosed purposely or accidentally to receptive individuals and organizations. As such, governments have enacted legislation in attempts to protect the individual’s right to privacy.

Interpretations of the right to privacy have filtered through the educational system. While teaching a masters-level graduate course delivered at a distance via the Internet (online), the authors discovered that the learning management system (LMS), Moodle, had been programed to display identification codes rather than students’ names when the course was presented in the Student View. (The authors had not detected this idiosyncrasy previously as the Instructor View contained the first name and surname of each student.) As a result, when students participated in forum discussions, their posts were attributed to their computer-generated identification code. Their peers were also represented by identification codes. Further investigation revealed that the institution had adopted the identification code protocol in order to comply with FOIP legislation. We wondered how the use of identification codes affected our strategies for creating a supportive learning environment and a cohesive online community of learners.

Given that the particular interpretation of FOIP and the institutional decision to assign numeric identifiers to all students using the LMS was likely unique to the institution, the situation provided an opportunity to gain insight into student identity and satisfaction with online social interactions. As such, this preliminary study investigates how graduate students perceived the experience of being represented by an identification code while studying in an online course. Specifically, it addresses the question: How does being represented by an identification code affect a student’s sense of personal identity within the online learning environment?

The impetus for the institutional decision to assign identification codes was to protect students’ privacy as legislated by the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act. The stated purpose of the Act is to control the disclosure by public institutions (including universities) of personal information from individuals. Personal information includes any identifying information about an individual. The Act applies to all teaching materials (Government of Alberta, 2008). In efforts to protect the privacy of students, the institution had adopted a policy of using identification codes instead of names in online course interactions.

In the past, when the delivery of distance education was via the postal system, interaction with peers was non-existent. Privacy was easy to maintain with correspondence. Students had no contact with their peers and only limited contact with an instructor or tutor. The advent of the Internet and emergence of Computer-Mediated Communications (CMC) revolutionized the delivery of distance education. The primarily student-content interaction of the correspondence model was transformed to include student-student interaction and greater student-instructor interaction. CMC facilitated the development of personal interactions within online courses, and was associated with numerous positive outcomes including enhanced community cohesion, improved higher-level learning and critical thinking abilities, better academic performance, increased motivation, and greater satisfaction with the course and/or program (Moisey, Neu, & Cleveland-Innes, 2008).

CMC interactions provided opportunities to overcome isolation, to listen, and to be heard. As LaraC3 described in the opening quote, CMC provided students with a voice, with a means of engaging with others in the course, and ultimately, with learning. The increased social presence afforded by the technology also prompted concerns about personal privacy and the potential risks associated with the inappropriate disclosure of information.

However, the issue of personal privacy contrasts with the disclosure of information among learners for the purpose of personal interaction. As such, we contend that maintaining individual privacy by not disclosing personal information within the online learning environment interferes with the conditions for building a supportive learning community. As LaraC3 stated earlier, her learning was tied to being heard by her peers. Peer interactions, meaningful discourse, and mutually beneficial collaboration and communication promote a sense of community among learners and facilitate learning. As such, we question how the non-disclosure of personal identity affects the online learning environment.

The term identity is used frequently and has many meanings. For this reason, a review of the etymological meaning of the following terms can bring clarity to our concerns: identity, identification, name, and code.

Identity – the quality or condition of being the same, in a sense individuality or personality. From the Latin word idem abbreviated as id meaning the same name (Oxford University Press, 2011).

Identification - The determination of identity; the action or process of determining who a person is; recognition (Oxford University Press, 2011).

Name - is a derivative of "know," which means to be assured of, to recognize (Skeat, 1882).

Code - has roots in the Latin word codex, which is a book of laws or collection of statutes (Oxford University Press, 2011); means "cipher" in the sense of a secret code (Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

Etymologically speaking, the terms identification, identity, and name are intertwined. Personality, individuality, and name are considered to be “the same.” A name provides recognition of a person’s unique individuality. Gadamer (1960/2004) states that the Greek expression for word, onoma, also means name, and notes that “A name is what someone is called and what he answers to. It belongs to the bearer.” (p. 405). Conversely, a code for identification creates secrets that must be deciphered by others.

Our personal identity is the condition or fact of being one person through various phases of existence (Oxford University Press, 2011). We contend that our personal identity should carry through into the online environment as another phase of existence. The use of a code for identification purposes in the Moodle LMS creates obstacles and hinders the development of personal identity, i.e., the condition of being the same person in the online environment as in other areas of existence.

Designated and Actual Identities

Sfard (2008) defined identity as a “a set of reifying, significant, endorsed narratives about a person” (p. 298). Identity was operationalized through subjectifying the process of objectifying I, you, and she. Sfard and Prusak (2005) pointed out that identity was linked to the activity of communication, rather than to traditional notions of personality, nature, or character. They further delineated the area, explaining that actual identities consisted of stories about an actual state of affairs; whereas, designated identities were about the potential to become an actual identity. Designated identities were not necessarily desired, but were perceived as binding. Frequently, designated identities were imposed by a different narrator (Sfard & Prusak, 2005). To elaborate upon this distinction, actual identities are usually told in the present tense (e.g., I am a student, I am a mother). Designated identities are stories that have potential to become true and are often told in the future tense (e.g., I want to be more proficient with technology, I should be more assertive). Designated identities shape people’s actions and choices allowing them to be closer to their actual identities, often without realizing there are alternatives. When designated and actual identities are further apart, individuals may experience unhappiness (Sfard & Prusak, 2005). An identification code acts as a designated identity, imposing a numerical designation onto an individual’s actual identity.

Gadamer (1960/2004) cautions that when a name is given and then altered, it “raises doubt about the truth of the word” (p. 405). From Gadamer’s perspective, the designated identity created by an identification code is an altered name, which raises doubt about the truth of the name. So how does this altered name, i.e., designated identity, affect recognition and trust within an online learning environment?

Identity in Community

Establishing identity is considered crucial to the formation of a learning community and for the construction of knowledge (Wenger, 1999). Wenger defined identity as something lived — a continual and ongoing process of becoming. Our identities transform through time and different contexts. Identity is socially established and negotiated through community. Identity formation is the interplay between identification and negotiation through engagement and alignment with community. Identity is socially constructed and is constantly negotiated and re-created with others (Wenger, 1999).

Mediated Communications

Effective social interaction is challenged when technology mediates interaction. The lack of social cues makes mediated communication more difficult than face-to-face interaction (Agarwal & Ma, 2007; Blanchard, Welbourne, & Boughton, 2011; Walther, 1992). On the other hand, the lack of contextual cues in mediated interactions can mitigate biases such as gender, ethnicity, and social status. Participants can project their desired image. Lack of opportunity for visual value judgments creates a "leveling" effect that enhances the learning of students who might be otherwise disadvantaged (Ross, Crane, & Roberston, 1995).

Despite the lack of social cues, meaningful interpersonal interactions can and do occur in computer-mediated communication (Gunawardena & Zittle, 1997; Walther, 1992). In experimental groups where the participants had no prior history, “CMC users formed increasingly developed impressions over time, presumably from the decoding of text-based cues” (Walther, 1993, p. 393).

Identity is considered important in technologically mediated environments (Turkle, 1995). In this context, our identity is the aspect of ourselves that distinguishes us from the technology, reminding others that we have bodies, emotions, and an intellect. In this way, identity can be considered within the framework of the sameness of two qualities: the person and the persona. The determination of one’s identity online can have both positive and negative effects. Turkle (1995) cautions that perceived breakdowns of identity in online environments can cause anguish for people. Negotiation of identity in online environments contributes to knowledge building (Agarwal & Ma, 2007; Ke, Chávez, Causarano, & Causarano, 2011; Rourke, Anderson, Garrison, & Archer, 1999). Individual control over identity, time, and presence with educational social technologies encourages learning (Anderson, 2008). As a socially negotiated process, identity is strongly connected with social interaction and learning in online environments.

In their model of online trust, Blanchard, Welbourne and Boughton (2011) defined identity processes as establishing one’s one identity and learning the identity of others. They contend that individuals establish their identities through the use of identity technologies by creating their own usernames, avatars, and signature files. (A signature file contains personal and professional biographical information.) To develop their model, Blanchard, Welbourne, and Boughton surveyed 277 members of 11 active virtual communities. They found that identity processes combined with the processes of observing, engaging, and exchanging information and emotional support (i.e., social exchange processes) contributed to online trust in virtual communities. Learning and creating identity lead to the development of and adherence to group norms, and to the growth of online trust in virtual communities.

Agarwal and Ma (2007) argued that perceived identity verification, i.e., “the extent to which individuals believe they are able to successfully communicate their online identity (who the individual is in an online community), relates – both directly and through mediation by satisfaction – to knowledge contribution in the community” (p. 43). In their study, Agarwal and Ma collected 500 completed survey responses from members of two online communities with over 3000 messages: a support site for cessation of smoking and a luxury car information exchange site. In both groups, individuals chose their own usernames, avatars, and/or nicknames. Their analysis revealed that perceived identity verification was a predictor of satisfaction and knowledge contribution.

Agarwal and Ma (2007) also found that three Information Technology (IT) artifacts -- virtual co-presence, self-presentation, and deep profiling — contributed to perceived identity verification by enhanced self-presentation.

Agawal and Ma found that persistent labeling did not contribute to perceived identity verification. Changes in identification did not influence understanding as long as the change was communicated to others in the group.

Social Identity

Similar to the opening quote in which LaraC3 expressed the desire to have her voice heard by her peers, Cohen and Metzger (1998) argue,

[u]nderlying the motivations for both mediated and face-to-face communication is a basic need for social affiliation. The need for social affiliation is so central for communication because it stems from, and is necessary for, understanding of who we are in relation to the world around us. (p. 41)

Addressing students by name contributes to the cohesion of the group (Rourke et al., 1999). Crabhill (2010) claims that our social identities are formed in memberships with other groups. We strive to remain part of the group if it has a positive impact on our social identity. In CMC communications, learners interpret text-based cues to evaluate others within an interpersonal framework. Screen names or constructed pseudonyms can serve as a means of identifying with the group. The ability to choose a screen name rather than to be assigned a username provides opportunities for participants to reveal information about themselves (Crabhill, 2010; Heisler & Crabhill, 2006).

Heisler and Crabhill (2006) found that individuals used email usernames as a basis for constructing perceptions about other individuals. They analyzed 300 survey responses from undergraduates and found the following:

Usernames provided opportunities to display information such as gender, age, race, and ethnic background, as well as interpersonal characteristics. Plain (i.e., assigned) usernames were associated with high uncertainty and were viewed negatively. Assigned usernames offered no insight into the group member’s persona. Chosen usernames were recognized as an opportunity to reveal information about oneself to others (Heisler & Crabhill, 2006).

However, some argue that disclosing too much salient personal identity is counter to community formation and undermines the shared group identity (Blanchard et al., 2011; Rogers & Lea, 2005; Walther, 1992). Too much personal information can take the group off task. Rogers and Lea (2005) suggest that all personal information about the group members should be concealed, arguing that the removal of these details from the initial group communications can serve to focus attention towards the goals and norms of the collaborating group.

To summarize, a person’s name belongs to the bearer and is how he or she is known within a community. Our identity is socially established within community. The lack of non-verbal cues in the online environment makes it challenging to learn about others within the community. Being called by name in CMC helps to develop trust and group cohesion. A chosen name provides cues about gender, race, age, and interpersonal characteristics. Conversely, assigned names or identification codes are less interesting and offer fewer insights about the person; moreover, they create a designated identity that may interfere with the development of trust and connectedness within the learning community. A sense of belonging contributes to group cohesion as individuals strive to remain part of a group when it has a positive impact on their identity.

Gadamer (1960/2004) reminds us that “understanding begins … when something addresses us” (p. 298). From Gadamer’s perspective, conversation is the point of inquiry. A conversation is not a predetermined explanation, but a negotiation of understandings. Conversation requires a commitment to consider the other’s opinion, rather than to “argue the other person down” (p. 367). A conversation begins with a question where the answer is unknown.

We have experiences when we are shocked by things that do not accord with our expectations. The questioning is more of a passion than an action. A question presses itself on us; we can no longer avoid it (Gadamer, 1960/2004, p. 366).

As described earlier, this study began with the recognition of the differing use of student names and identification codes between the Instructor and Student views in the Moodle LMS. We were shocked to discover that students were not identified by their given names but were represented by an alphanumeric code. When we learned about the protocol for using identification codes, we were pressed to know more. In order to understand what identification by a code meant to our students, we engaged them in a conversation (Gadamer, 2004), albeit an asynchronous conversation. We began this inquiry simply by posing the following question to students: “How is your identity affected by being represented as an ID instead of a name in Moodle?” We gained insight by considering their opinions.

The course. The course used for this study was an introductory course in an online Master’s of Education program. For most of the learners, this was their first course in the program. For many, this was their first graduate and/or online course. The 13-week course was delivered via the Moodle Learning Management System.

There were 34 students enrolled in the course. The students came from diverse undergraduate backgrounds and professions including nursing, dental hygiene, business, and education. Within the course, students participated in asynchronous online discussion forums (CMC) as part of the course requirements and grades were assigned for participation.

At the outset of the course, each learner was assigned an automated identification code containing characters from the student’s first and last name and a series of numbers. Within the Moodle LMS, learners can voluntarily add personal information and upload a picture to their profile page. This profile page is available to other learners in the class. The profile picture appeared beside each learner’s identification code with each posting in the asynchronous discussion forum. If there was no profile picture, a generic image appeared.

Data collection. We examined the text conversations of 24 learners enrolled in an online graduate course. In the first CMC forum, we posted a thread that asked the following question: “How is your identity affected by being represented as an ID instead of your name in Moodle?” The participants willingly shared their reflections in an asynchronous forum discussion. Within a day, 24 of the 34 students enrolled in the course (70.6%) responded to the question. The forum discussion yielded a total of 33 postings. A redacted transcript based on these postings formed the data for this preliminary investigation. The redacted transcript was constructed by compiling the postings in a MS Word file and removing any potentially identifying information. The code names of the students were changed; however, the same configuration of alphanumeric characters was maintained of six alphabetic characters and one or two numeric characters (e.g. DrakCo4).

Data Analysis. Qualitative research methods can provide generous insights into the phenomena of identity in online learning (Conrad, 2002, 2005). For the purpose of this investigation, a qualitative thematic analysis of the redacted transcripts was conducted. The posting was identified as the unit of analysis. Most postings contained a single message or meaning (thematic category) and were given a single code; however, a few postings contained two messages or meanings and were coded in two categories.

In an iterative and inductive process of comparative analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1998), we revisited the transcripts to draw interrelationships, categories, and themes associated with the learners’ experiences of being represented by an identification code in the online environment. We began by reading and rereading the postings, developing a categorization for each message, rereading the messages, and finally developing themes. We noted differences in what graduate students thought identity and identification meant to them. This process of qualitative analysis is found frequently in academic literature (Barbour & Hill, 2011; Owens, Hardcastle, & Richardson, 2009; Surry, Grubb, Ensminger, & Ouimette, 2009).

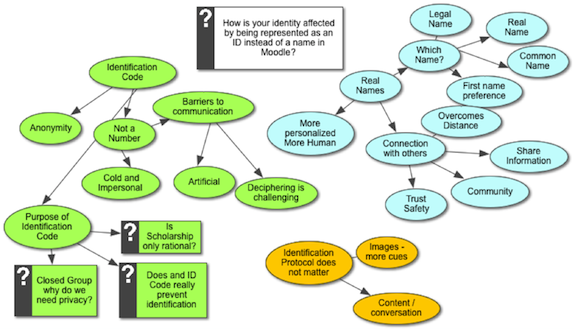

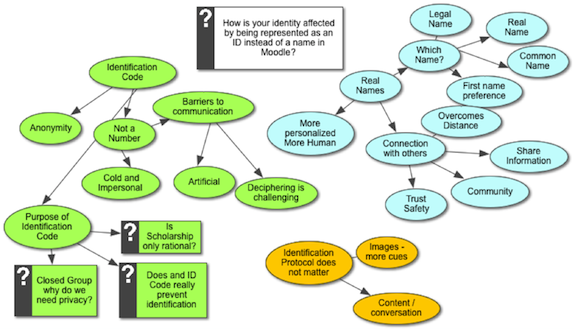

We coded the transcripts collaboratively. When there were differences in coding categories or themes, we discussed the discrepancy until we achieved consensus. The concept-mapping software package, Inspiration™, was used to provide a visual representation of the analysis. The non-linear nature of Inspiration TM facilitated the emergent categorization and themes.

The participants in the study were asked how being represented by an alphanumeric identification code rather than by name affected their identity in the online learning environment. Analysis of the 33 messages is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Inspiration™ visual representation of thematic analysis.

Analysis of the 33 forum postings revealed that the major themes of the conversations were about the use of real (i.e., given) names and identification codes. Conversations about real names questioned which real name was the most suitable, and discussed how names were more humanizing and helped to make connections with others. Conversations about identification codes asserted participants’ viewpoints about not being a number, discussed how anonymity may facilitate easier communication for introverted students, and questioned the purpose and effectiveness of using identification codes.

The thematic categories are discussed in more detail in the sections below.

Real Names

Which name? There was considerable debate about which real name to use. The university requires that students provide their legal name. A few students explained that they commonly use a different name than their legal first name. Some used their middle name, a shortened version of their first name, or a nickname. One participant recalled that the use of his first name invoked memories of being yelled at by his mother. A few participants concurred that an individual’s preferred choice of name would be the most suitable, as evidenced by the posting below.

Using a 'preferred' name would be ideal. It would be better to just get students to use their preferred name ------- SandAw5

More human. Being known by a real name was considered to be more humanizing and personal.

I'll just say that having a name instead of the ID number is more personal and I like that aspect. --- PameHa4

It (first names) definitely makes it more 'human.' --- MandTu1

I also prefer being looked at as a person not just a number. So just having my name posted is a good start --- DrakCo4

Connections with others. The use of an actual name was considered to facilitate trust, foster relationships, and create a sense of warmth and safety, which all contributed to a sense of community. Sharing information was perceived as part of developing community. The social connection helped facilitate learning. Postings, such as those below, were included in this theme.

I feel the use of names helps to develop a therapeutic relationship. It enables to build trust when someone takes the time to identify with us by name, it shows that they see us as individual unique people. ----- LiamJo30

I agree with everyone using your name helps to empower ones self in a learning community like this one. It helps to foster relationships and build a sense of a warmth and safety. ----- LeanCh1

As humans, I feel that when we engage in any form of communication we want to identify with someone especially if we have common goals. For me personally, I want to be able to identify with that person in name and picture to give the best response. If anything we need to foster a sense of connectedness in this technical world even if it is only in a name. -------- JoanFr12

Identification Codes

Not a number. Several participants stated strongly that they were not numbers and that being identified by an ID depersonalized them. They found identification codes cold and impersonal, and wanted to be known as more than a number. Representation by an identification code was likened to being known as a patient by the diagnosis or the room number in a hospital, e.g., “the appendectomy in 204.” The following posting exemplifies the “not a number” type of message:

ID's are impersonal and only speak to the relationship which generates that ID e.g. an employee number. Each of us is much more than that. ------ MichMc10

One posting noted how the use of identification codes seemed anonymous, shady, and secretive in nature.

Usernames seem so -- I don't know -- anonymous -- like we are trolling for unsuspecting underage sexual victims or sleazy one night stands. We are not. (Well, I am not, anyway). ------ NichVo1

Barriers to communication. The artificiality of identification codes made communcation more difficult as noted in the following posting:.

Being addressed by an ID number is not real. Therefore ID numbers are a barrier to communication. -- ElisCh1

Another identified barrier was the cognitive challenge of deciphering identification codes into names.

When I see the ID, and knowing there are many individuals with a variety of spellings of names from different countries, visually I have to take a second look as I do not want to address the person with an incorrect name and offend that person. For example - - the other day I addressed – a gentleman as “Carmen” when his name is actually “Cameron” ---- ShelTe1

Purpose of identification code. A couple of participants questioned the issue of privacy. They felt the issue was moot for a couple of reasons. First, the ID was generated from the student’s first name and first two letters of the last name, so it was easy to guess the name of the person. With a little deciphering, the generated ID revealed the student’s identity. Similarly, if a profile image was posted, privacy was reduced or eliminated. They felt that identification codes did not really provide privacy. Second, the class was a closed group. A student pointed out that participants wanted to make both personal and professional contacts in the course, and asked, “Was it not one of the purposes of taking a course to get to know peers? Why was privacy needed in a closed group?” Another participant questioned whether scholarship was entirely rational or was there room for affective emotions?

A couple of students were not as concerned with the use of identification codes; both had taken previous courses in the Masters program. One student noted that it was the content that made the discussions worthwhile.

However I must also say that in my last course ID s were kept (although we often signed our names) and the discussions were wonderful! I believe that whether ID s or names, it is the content of the conversation that is the most pertinent -------- AnglV35

A couple of students thought that the anonymity of an ID might help more introverted individuals overcome their shyness.

I feel like an online ID can almost mask our identity by giving an element of anonymity. I think that element of anonymity could be positive though if it encourages students to participate in online discussion who otherwise wouldn’t have the confidence to participate in face-to-face classroom discussions. I’ve worked with [members of a profession] in the past who really struggled to participate in classroom discussions and I think they would be much more comfortable communicating in an online forum. I also think it can be a confidence booster and that may come from the responses of others as well ---- DianFo8

Sometimes having the ID instead gives people, who otherwise would avoid contributing, the chance to communicate with the group without completely exposing who they are. ----------- PameHa4

In summary, most participants wanted to be known by their own names, i.e., by their legal first name or by the name they were known. The use of identification codes was considered offensive and dehumanizing, and was seen to create barriers for establishing connections with others. Two students with prior experience in the online program were less offended as they knew that obstacles could be overcome and quality communication was possible.

Qualitative research is not intended to be objective. As instruments in the research, researchers’ biases are unavoidable. Bias occurs in the questions asked and in the analysis. However, the collaborative coding of the transcripts helped to ameliorate bias and increase the rigour of the study. The detailed description of the study’s method allows readers to formulate their own understandings of the biases of the researchers in this study.

Generalizations to a broader population are not possible with qualitative research although the findings may be transferable to other settings or provide insights into similar situations.

Technological advances in online communications have created tension between the student’s right to privacy and the need for effective communication in an online learning environment. In efforts to comply with FOIP legislation and to protect students’ privacy, the institution adopted a policy to assign computer-generated identification codes to represent students in the Moodle learning management system. All student contributions, including postings in asynchronous online text-based forum discussions, chat messages, email messages, and student profiles were attributed to their assigned identification code.

In the course, participating in the discussion forums was mandatory and grades were assigned for participation. In these discussions, participants were represented by a computer-generated identification code. When asked about this practice, most of the participants spoke against it and some strongly resented the protocol. Only two students were not uncomfortable with the practice, placing greater value on the content of the conversation than on the identity of the other participants. These students had experienced similar online courses and, as such, likely had a stronger identity as an online graduate student and more confidence in their ability to project their identity beyond their name.

For many students, this was their first online course and their first experience communicating with peers in an online environment. Being identified by a code rather than by name came was unexpected, and caused them to feel depersonalized, dehumanized, and objectified. These students clearly stated that they were not a number and desired their personal identity to be consistent in the online environment. Students wanted to network with their peers for professional and personal reasons but identification codes made it more difficult for them to get to know each other. Consistent with the etymological definition, the use of a code created “secrets,” which the participants had to decipher in order to identify each other. Similarly, paralleling Gadamer’s (1960/2004) notion that altered names raised doubt, participants mentioned that the assigned alphanumeric code name (which created designated identities) caused them to feel that something was hidden and created barriers to communication and the development of relationships. Similar to Turkle’s (1995) observations that the breakdown of identity may cause anguish, the realization that they were being identified by a code name affected the students’ sense of identity and resulted in feelings of discomfort, disappointment, and even dismay.

As Sfard and Prusak (2005) note, over time designated identities can become actual identities. Because their designated identities were consistent, the participants in this study did get to know each other. Agarwal and Ma (2007) refer to this process as perceived identity verification. In some postings, participants addressed each other by their designated code name. The use of personalizing tools, such as profile pictures and bio pages, helped students establish how they were known online, and some participants noted that the profile images were useful for identifying peers in the discussion forums.

Although students register at the university by their legal first and last names, using (or publishing) these names in the LMS system may violate FOIP. So how can a university, a public institution, protect the privacy of its students? The answer to this question comes from the participants themselves: as FOIP permits the publishing of voluntary information, we should allow students to volunteer the name they wish to be known by in a course.

The participants in this study, including LaraCE3 in the opening quote, described their need to be heard and to listen to others, as well as to connect and feel they belong. Creating an online learning environment in which these needs can be met is a challenge. Building a cohesive scholarly community requires that we support and contribute to, not interfere with, students’ identity. Identifying students by their preferred name alleviates the discomfort and disorder caused by the use of identification codes.

While this paper reports on a small preliminary study in a context that is likely unique to one institution, our findings underscore the importance of identity for online learners. Student identity is an important consideration for online instructors, as well as for those involved in related areas such as instructional design, learner support, and policy making. Further research is needed to learn more about how identity is established and maintained in online learning environments, how complex systems of identity form and function in online learning communities, and how institutional issues with FOIP and other privacy-related policies should be addressed.

Krista Francis is IOSTEM Interim Coordinator, Faculty of Education, University of Calgary. E-mail: kfrancis@ucalgary.ca

Susan Moisey is an Associate Professor, Center for Distance Education, Athabasca University. E-mail: susanh@athabascau.ca