Vol. 36, No. 1, 2021

Abstract: Using Giorgi’s descriptive phenomenological psychological method and a social work disciplinary lens, this Canadian study explores how women in online learning contexts experience and recover from depression. The primary research question guiding the study was, “What are the lived experiences of women in online learning who have lived with and recovered from depression?” The goal of the study was to provide a general description of the structure of this lived experience. Ten women who suffered and recovered from an episode of major depressive disorder during their online studies were interviewed. Seven invariable constituents of the experience were identified, including the development of depression, the impact of depression on learning, the treatment of depression, the importance of peers in online learning, the experience of role overload, changes in self-identity, and the application of personal agency. The study provides recommendations for institutions, educators, and course designers to increase peer interaction and provide direct in-course links to student support.

Keywords: online learning, women, depression, post-secondary, phenomenology

Résumé: En utilisant la méthode psychologique phénoménologique descriptive de Giorgi et une optique disciplinaire de travail social, cette étude canadienne explore comment les femmes dans des contextes d'apprentissage en ligne vivent et se remettent de la dépression. La question de recherche principale qui a guidé l'étude était : " Quelles sont les expériences d'apprentissage en ligne vécues par les femmes ayant eu une dépression et s'en étant rétablies ? ". L'objectif de l'étude était de fournir une description générale de la structure de cette expérience vécue. Dix femmes ayant souffert et récupéré d'un épisode de trouble dépressif majeur pendant leurs études en ligne ont été interviewées. Sept composantes invariables de l'expérience ont été identifiées, notamment le développement de la dépression, l'impact de la dépression sur l'apprentissage, le traitement de la dépression, l'importance des pairs dans l'apprentissage en ligne, l'expérience de la surcharge de rôles, les changements dans l'identité de soi et l'application de la responsabilité personnelle. L'étude fournit des recommandations pour les institutions, les éducateurs et les concepteurs de cours afin d'augmenter l'interaction avec les pairs et de fournir des liens directs dans les cours pour soutenir les étudiants.

Mots-clés: apprentissage en ligne, femmes, dépression, post-secondaire, phénoménologie

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Megan’s experience of depression took place in the early days of her graduate program and was triggered by a financial loss after a contractor damaged her home and stole her deposit worth many thousands of dollars. At the time, Meagan was working full time and caring for her young son in addition to her coursework. Megan experienced panic and extreme sadness. She found herself unable to concentrate or think clearly, had difficulty getting out of bed, and eventually started calling in sick for work.

Megan’s story is not unusual. Many students will experience depression and other mental health challenges during their post-secondary education, about twice as many women as men (Pearson et al., 2013). The research literature on post-secondary student mental health, however, including the literature on depression, has focused primarily on face-to-face post-secondary environments. This study shifts that focus and explores how the context of online learning may shape the experience of female learners with depression. The study is grounded in the lived experiences of the research participants and reflects the need to make visible a population of learners whose experiences are relatively scarce in current scholarly literature.

The word “depression” is widely used in a colloquial sense. Meanings can range from having a bad day at work to describing a significant loss of functioning. This study used the definition of major depressive disorder from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), chosen because of its wide use both in the diagnosis of mental disorders and in large population studies. The World Health Organization (2017) estimates that more than 300 million people suffer from depression worldwide, and it refers to depression as the “single largest contributor to global disability” (p. 5). Numerous studies have shown that the experiences of mental health and mental disorder differ according to gender (Afifi, 2007; Angst et al., 2002; Dalgard et al., 2006; Kessler, 2003; Piccinelli & Wilkinson, 2000). Using data from Statistics Canada, Pearson et al. (2013) found that 11.3% of Canadians suffered from major depressive disorder. Their study showed higher rates of depression for women across all age categories under the age of 65 years, with the highest rates occurring in the 15–24 years age group. In this age group, women’s rates of depression were almost double those of men (Pearson et al., 2013, p. 6).

Phenomenological studies of women with depression reviewed are few and do not address post-secondary populations. Four phenomenological studies reviewed employed a range of approaches to explore older women’s experience of depression (Allan & Dixon, 2009), women’s experience of depression at midlife in Taiwan (Li et al., 2017), the experience of depression among low-income South African women (Dukas & Kruger, 2016), and the essential meaning structure of depression in women (Røseth et al., 2013). Røseth et al. (2013) used Giorgi’s (2009) descriptive phenomenological approach to describe the experiences of three women from outpatient psychiatric clinics in Norway. This study is the closest in methodology and aims to the current study.

Many post-secondary institutions across North America take part in the National College Health Assessment (NCHA), a national research survey organized by the American College Health Association (2019) to assist college health service providers, health educators, counsellors, and administrators in collecting data about their students’ habits, behaviours, and perceptions on prevalent health topics. This survey was conducted at the online university where the current study took place. The survey revealed that 32.1% of respondents had been diagnosed with depression at some point, compared with 22.2% of the reference group (Krasowski, 2018). Gender differences in diagnosis of depression were 15% male and 25% female, which was similar to the reference group. Krasowski (2018) recommended caution in interpreting results since the response rate to the survey was 12%, which was slightly lower than the reference group.

Quantitative studies have provided a gendered analysis of students’ frequency of symptoms and diagnoses of mental disorders, including depression, in post-secondary environments and, more recently, online learning environments. Missing from the literature are qualitative studies that attempt a deeper understanding of that experience. The significance of the current study is its attempt to give voice to women’s experience of and recovery from depression during their online studies.

The descriptive phenomenological psychological method of Giorgi (2009) was used in the study to answer the research question, “What are the lived experiences of women online learners who lived with and recovered from depression?” The study was approved by the research ethics board of the large Canadian online university where the study took place. A purposive sample of 10 women (seven undergraduate students and three graduate students) was obtained. Students in the sample came from a variety of academic programs. Inclusion criteria were that students were enrolled in a degree-granting program at the online university at the time of the study, had completed a minimum of three courses in their program of study, had experienced depression at some point during their online post-secondary studies, had been diagnosed with depression by a health professional, and had recovered from depression prior to being interviewed.

Participants were also asked if their program included a cohort component. Each woman who agreed to take part in the study was interviewed once by phone. The semi-structured interviews were approximately 40 minutes in length and were audio recorded. Audio recordings were transcribed, and any personal identifiers removed. The women were invited to review the transcripts for accuracy and to choose a pseudonym to be used for the analysis and write-up of the study.

Analysis began by the researcher assuming the phenomenological attitude, a disciplinary perspective (in this study, social work), and sensitivity to any implications of the data for the phenomenon being studied (Giorgi, 2009). Finlay (2009) describes the phenomenological attitude as an attempt “to be open and to meet the phenomenon in as fresh a way as possible, bracketing out habitual ways of perceiving the world” (p. 476). In other words, I attempted to be aware of, and manage, my own history and potential biases to be more fully present to the experiences of the women in the study. To assist me in assuming the phenomenological attitude, I practised mindfulness meditation for 10 minutes prior to engaging with the data, using a meditation app on my phone. I also engaged in reflexive journaling after working with each participant’s transcript using the memo function of the qualitative data software. NVivo 12 Plus qualitative data software was the software used in the analysis of the interview data.

Meaning units were identified in the transcripts. In this study, transcripts were reviewed with the phenomenon and discipline of social work in mind and demarcated at each shift in meaning. Although this shift might be detected after a statement or sentence, shifts in meaning could also be several sentences in length. This process resulted in second order descriptions which, in descriptive phenomenology, are considered invariant meanings (Giorgi, 2009). It is within this step of analysis that the phenomenological procedure of free imaginative variation was used to achieve a level of invariant meaning out of possible variations. In free imaginative variation, the researcher changes aspects of the phenomenon while in the phenomenologically disciplinary attitude to distinguish the essential, also known as invariable, features of the phenomenon without which “[the] phenomenon could not present itself as it is” (Finlay, 2008, p.7). Giorgi (2007) defined the meaning of imaginative variation as follows:

[a process in which] one imaginatively varies different aspects of the phenomenon to which one is present in order to determine which aspects are essential to the appearance of the phenomenon and which are contingent. If the imaginative elimination of an aspect causes the phenomenon to collapse, then that aspect is essential. If, on the other hand, the variation of an aspect of the given hardly changes what is presented, then that aspect is not essential (p. 64).

Imaginative variation introduces another level of interrogation to the analysis of the data where only the meanings essential to the experience are kept. Within this process, general structures, comprising invariable constituents, were identified across participant descriptions. Lastly, a final synthesis of the general structure of the experience from the invariable constituents was created, and follows (Broome, 2011; Shakalis, 2014).

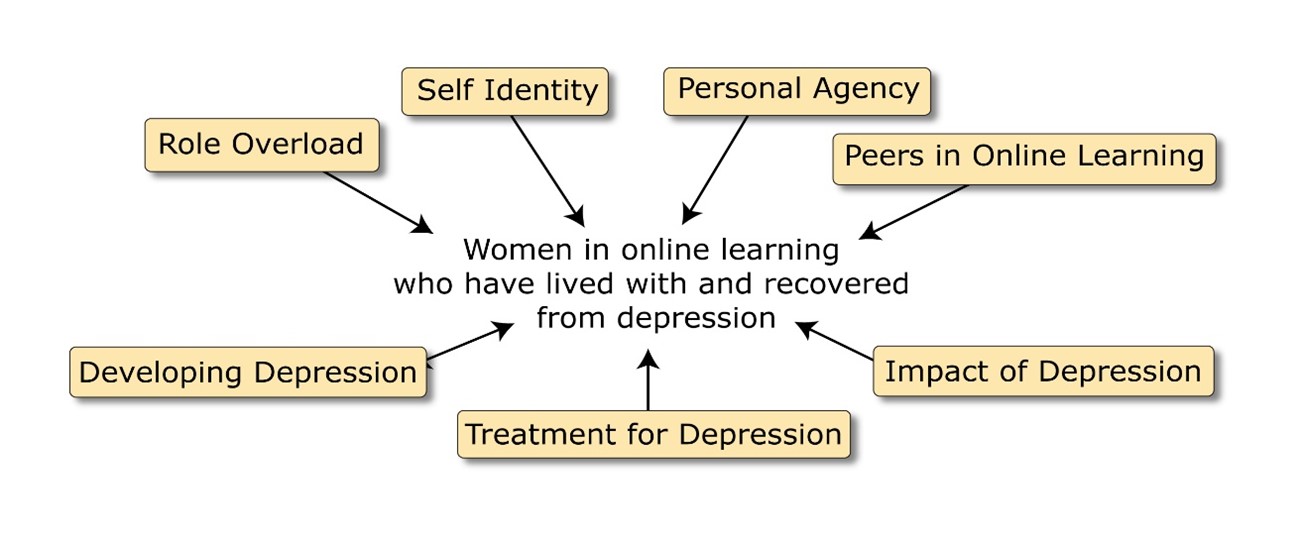

The interview data from the 10 participants yielded seven invariable constituents of women’s experience of depression during online studies. These constituents are: the development of depression while learning online; the impact of depression on learning; treatment for depression; the role of peers in online learning; role overload in women’s lives; changes in self-identity; and the role of personal agency including making use of the affordances of online learning (see Figure 1). What follows is an elaboration of each of the seven invariable constituents of the women’s experience.

Seven Invariable Constituents of Women’s Experience of Depression During Online Studies

For most of the women, the experience of depression during their online learning was not their first. Indeed, nine of the participants related experiences of depression dating back to adolescence or early adulthood. Co-constituents of developing depression while learning online included trigger events and symptoms. All women in the study traced the beginning of their depressive episodes to a response to one or more trigger events including the loss of a job, injury, financial difficulties, and, for several women, the pressure of academic performance. Katie shared her experience of developing depression:

It slowly crept up on me and I do think a lot of it is the course load and the amount of pressure from the program that I’ve put upon myself in a way because I was, it’s an intense program and I was trying to get through it, I’m trying to get through it as quick as I can. So, I don’t know, it was just, it kind of slowly crept up on me and before I knew it, I was just not coping and I was not able to function.

Another co-constituent of the experience of depression involved the experience of depressive symptoms. Elisabeth described her experience of depression:

I had just slow motor effect where I was just talking slow and I felt like just pushing through slog. Like your whole body is just dragging, your limbs are like, you know, like you just have trouble holding your body up. It was just so, it felt like cement blocks around my feet or something.

All the women described challenges in their ability to think, focus, and retain information from what they were reading. These challenges often resulted in late assignments, late posts to discussion forums, and, at times, an inability to complete assignments or courses. Justine described how depression affected her learning:

So, the depression definitely affects online studies. I was trying to carve out time, but I just wasn’t able to write. I would have things, chunks of material and content written out in paragraphs, but it didn’t make any sense.

Megan described her experience of depression as having a “really thin layer of cotton in the front of [her] brain or eyes” that made it difficult to understand what she was reading. Sometimes, she would stare at her computer for hours.

Treatment for depression was another invariable constituent in the experience of depression while learning online. The most common treatment that participants accessed was a combination of medication and counselling. Eight of the 10 women continued to take medication once their symptoms subsided as a means of maintaining their mental health. Megan’s experience with medication reflected the experience of many women in the study. She noticed that as the medication started to work, her ability to focus increased. She explained that the medication “allowed her to use her brain like a normal person” so that she could accomplish things and do the things that made her happy.

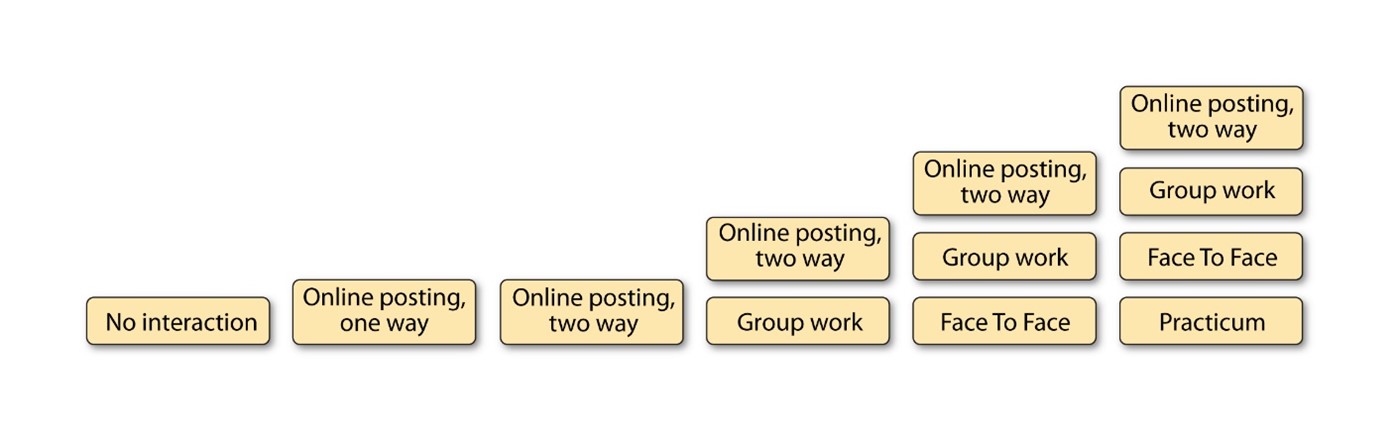

Figure 2

Continuum of Peer Interaction in Online Learning

The presence or absence of peer interaction was an invariable constituent of women’s experience of depression in online learning. Figure 2 illustrates the range of peer interaction experienced by the women in the study. Peer interaction ranged on a continuum from no interaction with peers to a high level of interaction including online discussion forums, group work, face-to-face (FTF) course components, and practicums. Students who were enrolled in bachelor level courses had the least interaction with their peers, and graduate students experienced the most. Students with the least interactions with peers most often described the courses they were taking as self-taught. Several students assumed that the lack of peer contact was just the reality of online learning. Isolation was challenging for students where no peer interaction was available in their courses. Amanda describes the importance of peer interactions in her online undergraduate studies:

I found it hard in general because I didn’t have any social interaction. When I originally started, I was taking one or two classes at a time and working full time. So it wasn’t, it wasn’t as bad because I would go to work and I would have that social interaction with people and even though I’d do school at lunch, I’d talk with co-workers. But it was about a year in that I quit my job to do school full time to get it done. That was the hard part. I think I lost that social interaction… It was horrible. I mean, I sort of lucked out when, because I had a cousin who began attending [FTF university] and when I’d find out she was there studying at the library, OK, I’m coming to join you. I don’t care if you talk to me. I’m just coming because I can’t be on my own, alone. My dogs are great, but I need real people.

Jasmine, also an undergraduate student, felt isolated. With no reflection of her experience through peers, she did not have a realistic view of her student self:

Being alone and as much as I try not to compare myself to other people, but I feel like sometimes in [FTF] school that helps. Like in situations where I’m like, “Am I the only person that doesn’t understand this?” But then if other people don’t understand it, you don’t feel like you are, dumb. I kind of feel like online school put me in a situation where I was constantly comparing myself to a student that doesn’t exist, that was perfect and getting a 100 on everything and understanding everything. And I couldn’t live up to that expectation.

Other students found themselves responding to discussion forums that were set up years earlier. With no feedback from these forums, they are described on the continuum of peer interaction in online learning as “Online posting, one way.” Two-way discussion forums did allow some students to develop peer relationships inside and outside of the course. For Justine, posts in course discussion forums helped draw her out of the isolation she was experiencing.

Although course instructors were mentioned a few times in the interview data, the absence or presence of peers was, by far, the most pressing concern for the women in the study. The type of peer interaction desired appeared to be one of commiseration and normalization of the role of student. There was a need to know that other students shared similar concerns and frustrations, including the difficulty of programs, topics, and assignments. It also helped to share worries and laugh with one another. For example, Megan completed both an undergraduate and a graduate program online. Megan, reflecting on a week-long FTF skills portion of her program, stated:

It was so nice because I actually got to meet some of these students that I’ll be graduating with that are sitting there in the same boat going, “What the fuck? This is so hard!” So, we all got to have meltdowns together. It was nice.

Most of the women in this study juggled many different roles in pursuing their education. The women were working full time as well as studying, and several were also parenting children. Role overload was an invariable constituent of women’s experience of, and recovery from, depression while studying online. Duxbury et al. (2018) define role overload as “the perception that the demands imposed by a single or multiple roles are so great that time and energy resources are not sufficient to fulfill the requirements of the roles to the satisfaction of one’s self or others” (p. 250). In some cases, participants responded to role overload by reducing their course loads or hours of work. Emily and Katie both expressed that full-time work and full-time study was an unreasonable expectation, or as Katie put it, “full-time studying and full-time anything.” At the time of Katie’s interview, she was taking four courses to be eligible for student loans as well as parenting a preschooler and newborn. Being depressed meant all her roles suffered. For Justine, getting home to make supper and help her daughter with schoolwork before getting to her own studying was a daily challenge.

Change in self-identity was an invariable constituent of women’s experiences. Most of the women experienced a depressive episode as being “not themselves” and recovery from depression as a “return to themselves.” People close to the participants also used the language of self and not self when referring to their loved one’s experience of depression. As the experience of depression shifted, the women described recovery as regaining their ability to study, complete assignments, and enjoy learning as well as other activities.

The final invariant constituent of women’s experience of, and recovery from, depression as online learners involved the application of personal agency defined as “the ability to initiate and direct actions toward the achievement of defined goals” (Zimmerman & Cleary, 2006, p. 45). The women in this study found many ways to persist with their studies despite their experiences of depression. The following sections elaborate on the women’s five most used affordances of online learning to manage their lives and studies.

Course extensions were used by some women to try and wait out the depressive episode until they felt able to re-engage with their coursework. Juliena paid for an extension knowing that her coursework depended on her time in the evening and weekends when she was most tired. Without extensions, Elisabeth did not believe she would have been successful:

Because of the university’s deadline, I extended [the course]. I knew in my head, I’m not mentally in a place to be able to do this right now. I’m going to push back how long I have to do the course and when I started noticing my symptoms abate… I was like “Oh good, now I can actually,” I’m like, “Today’s a good day.” Like not every day… On the days when you do feel good, “What can I do to feel productive?” you know?

In a more informal way, Justine reached out to her professors during times of the year when she knew she was more vulnerable to depression and let them know that she might require an extension. During these times, Justine paid attention to self-care, including getting adequate sleep, eating healthy meals, and making sure she maintained attachment with others.

It is important to note that not all the women found course extensions helpful. Brooklyn and Emily attempted to use course extensions in their undergraduate courses without success. Depression persisted for both women, and neither were well enough by the end of the extension to be able to complete the courses they were taking. What did work for Emily in her graduate studies was negotiating with her professor to get an extension on a specific assignment and a week off posting to discussion forums.

The flexibility of online learning was used by participants to help manage their experience of depression, especially fatigue. Brooklyn, like most of the women, was able to pursue post-secondary studies while still working. She felt that she would not have attended FTF classes because of the exhaustion associated with her experience of depression. It was easier for Brooklyn, and others, to attend online classes even when not feeling well. A concern Juliena had was that the effort of attending FTF classes when unwell or feeling depleted, rather than getting the rest that she needed, would trigger depression. Virginia found that she was able to catch up more easily in online studies after a difficult day, or days.

Several women in the study mentioned monitoring their online activity for possible relapse into depression. Noticing a decrease in her postings to discussion forums became a sign to Justine that she might be becoming depressed. Sharing ideas in online discussion helped draw Justine out of depression. She transformed the course requirement to post into a way of monitoring her mental health.

Self-management included a variety of strategies that the women used to continue their online studies while suffering and recovering from depression. These strategies included reducing course and/or work loads, negotiating changes in employment, and increasing self-care. Emily reduced her work hours from working full time at the beginning of her program to working 2 days a week.

Megan and Juliena negotiated with their employers to complete coursework and maintain self-care practices. When Juliena started a new employment position, the change in routine made it difficult to keep running, which was a key activity in maintaining her mental health. Juliena negotiated the maintenance of her running routine with her new employer. She also negotiated study time.Self-care was mentioned repeatedly in participant interviews. Concomitant with the experience of depression and role overload, women’s own personal needs and self-care activities were often the first to go out of a long list of priorities. When Megan talked about self-care, she really meant that she needed her people. Megan developed a support system and learned to recognize when she was becoming depressed, and then sought out someone with whom she could discuss her thoughts and feelings. Juliena learned to manage her life and schedule differently to keep herself well. Knowing that overstimulation drained her, she allowed herself to come home from work or change plans to accommodate her need to rest.

Most of the women mentioned the importance of keeping themselves organized as well as appreciating well-designed and detailed expectations and timelines in undergraduate courses. When Brooklyn was depressed, she had increasing difficulties in keeping herself organized. Organized course design was very helpful for her when she was depressed. The detailed week-by-week expectations helped her plan her studies when she was struggling.

Emily also felt that program design was a factor in managing depression as a student. She was one of the two women who completed an undergraduate degree online and was able to compare experiences of online undergraduate and graduate programs. She felt that program design was a big factor in differentiating her undergraduate and graduate online learning. Emily viewed the graduate course design and delivery as easier and friendlier to people struggling with depression.

The most common way that participants coped with depression and multiple roles was to carefully schedule coursework, family commitments, and work life. When recovering from depression, Elisabeth worked with her counsellor to first schedule self-care activities and then moved on to schedule school activities as a part of her routine. Katie planned out her coursework to meet deadlines, writing out a schedule that included deadlines and weekly activities to keep her on track to complete her course. That way, if she noticed herself falling a bit behind, she could catch up in time. Virginia also planned out her schedule as well as making task lists and using stickers and rewards for adhering to her schedule. Megan and Justine also described their strategies to keep organized, and included their multiple role commitments in implementing their strategies. For example, Megan and her partner kept a large calendar at home where they put their activities and their children’s activities. To complete her class while waiting for the antidepressant she was prescribed to start working, Megan set out a schedule to the end of the semester and scheduled time into every day for her coursework. It was important for Megan to be accountable for what she had to do. Justine also scheduled her coursework around her own work and her daughter’s activities.

The goal of this study was to provide a general description of the structure of the lived experience of women who suffered and recovered from depression during their online studies using the invariant constituents discussed previously. The description is as follows:

The experience of major depressive disorder for women learning online starts with a trigger event that leads to a cascade of depressive symptoms. As online students, depression begins to impact the women’s ability to focus, understand and retain material, and complete assignments. Their academic performance suffers. Women access treatment for depression in the form of medication and/or counselling. The availability of peer contact and interaction in online learning affects the women’s experience of depression and how they view themselves as students. Women with depression as online learners experience role overload which contributes to the experience of depression. Depression also affects self-identity. Women experience depression as not self, and recovery from depression as a return to self. In the context of online learning this not self is reflected in decreased academic performance and failure or reduction in online posting. Recovery from, or management of, depression involves a return to previous levels of academic performance, including ability to focus, understand, and retain material, completion of assignments, and increased participation in online posting. Women demonstrate their personal agency in managing depression, including taking advantage of the affordances of online learning and practising self-management.

This study adds to our knowledge of women who experienced and recovered from depression during their online studies. Some of the most important findings are in their uniqueness to the context of online learning, including the role of peer interaction for students, as well as the role of personal agency in women’s use of the affordances of online learning and self-management.

Peer availability and variety of peer interaction depended largely on whether participants were enrolled in an undergraduate or a graduate program. A continuum of peer interaction was introduced previously. Graduate students had much more opportunity for interaction with peers, including participation in online discussion forums several times a week to 1-week FTF courses offered yearly and, for some, participation in practicum experiences. Undergraduate students had the least interaction with their peers, from no interaction and one-way interaction in a discussion forum to two-way interaction in occasional discussion forums. Virginia referred to this experience as “the double-edged sword” of online education, as if a trade-off were necessary in terms of connection with peers for the flexibility of online learning. Unfortunately, students without access to peers may accept that isolation is a necessary component of online learning rather than an institutional and design decision.

The experience of loneliness and isolation was most often experienced in undergraduate programs where peer interaction was limited or nonexistent. Most important in this study were women’s articulations of the type of peer interaction they desired. Participants in the study talked about the need to commiserate with other students and compare experiences and expectations of being students. They desired to see themselves reflected in the experience of others. Not being able to do so exacerbated the experience of depression. Kirsh et al. (2016) identify the importance of social support, family issues, and stigma to students with mental disorders. Social support was identified as having friends who helped students feel normal and who provided them with a sense of community. Weiner’s (1999) grounded theory research investigating the meaning of education for students with mental disorders posited the importance of normalizing students’ lives as a subtheme of student experience. Normalization of the student role in the form of commiseration and connection with others was desired by most of the women in this study. This may be particularly important in online environments where student interaction is only available by design.

Participants who were graduate students found that their interactions with peers resulted in greater opportunities to commiserate about course material and course expectations as well as sharing their experiences of being students. Opportunities for peer interaction led to the use of other modes of communication in the form of texting, chat apps like WhatsApp, phone calls, and FTF meetings. Subsequently, friendships developed. Two graduate students used their peer interactions in online forums as a means of monitoring depressive symptoms, and one participant credited this interaction as helping her recover from a depressive episode.

Participants made use of the unique affordances of online learning such as course extensions and flexibility. Although not successful for everyone, several participants credited course extensions as enabling them to “wait out” a depressive episode until their medication began to work. This observation is consistent with Moisey’s (2004) study finding course extensions the most common support used by students with mental disorders. In the current study, course extensions and, in paced courses, assignment extensions and modifications, supported several participants during episodes of depression. Of importance to participants was the flexibility unique to online learning that allowed women to study when, and where, they chose. This study identifies how flexibility was useful to women experiencing depression. Flexibility meant that, when depressed, women could wait for moments of clarity before engaging in their coursework and they could complete bits and pieces of their studies as they were able. The fatigue that accompanied depression could also be managed by studying from home or after resting rather than making the effort to travel to and from FTF institutions. Without the flexibility inherent in online learning, most of the women would not have been able to continue or complete their studies. As is the case with many online learners, the flexibility of online learning allowed women to continue their education while also fulfilling their roles as employees and parents, although fulfilling these roles often proved problematic.

This study illustrates the sequence of events in women’s development and experience of depression throughout their online studies. A depressive episode began with a trigger event followed by the development of depressive symptoms. In the phenomenological studies of Dukas and Kruger (2016) and Røseth et al. (2013), women also described the bodily symptoms of depression, although these themes and experiences are worded somewhat differently. These studies relied on study participants to self-identify as experiencing depression. Unique to the present study was the women’s diagnosis of major depressive disorder by a health professional. In addition, the present study followed the women past the initial experience of depression and into recovery.

The women expressed that managing their lives and depressive symptoms was essential to remaining well. A common strategy was to organize their time in terms of course expectations and family expectations. In their Canadian study, Kirsh et al. (2016) mention self-management over academic life as important to students with self-identified mental health problems. The students in their study valued having control over course load and scheduling.

Implications of this study include its relevance to post-secondary educational institutions in the design of online learning and approaches to student support. Participants described isolation in terms of lack of access to interaction with peers and identified the type of peer interaction that they most desired. Participants wished for opportunities to see their experiences and identities as students reflected in their peers. Effective peer interaction in online learning was essential to the well-being of women with depression. It was apparent in interviews with women, and the resulting continuum of peer interaction, that the isolation of students from their peers was the result of choices in course design rather than due solely to the experience of depression. Efforts to establish some form of peer interaction, including discussion forums in courses, and encouragement of social spaces both inside and outside of the course site (York & Richardson, 2012), would improve the experience of online learning particularly in undergraduate courses where students currently have the least peer contact. McIsaac (2021) found that using WhatsApp, a form of mobile instant messaging, successfully increased learners’ interaction with one another regarding their coursework, without any allocation of marks or any involvement of the course instructor. A form of peer interaction, this format would also allow for communication about the student role.

None of the women who participated in this study identified themselves to the university as having a disability. In addition, at no time during our interviews had the women referred to themselves as having a disability and, consequently, they might not have considered themselves to have one. This finding differs from McManus et al.’s (2017) study where participants with unspecified mental health disorders were recruited from the university’s disability services unit to confirm the diagnosis of a mental health disorder. Most students in their study had additional health disabilities including sensory and physical disabilities. None of the women in the current study had accessed the university’s disability services.

Without registering with the university’s designated services to support students with disabilities, the students in this study and their experiences were essentially invisible to the institution and to their instructors. Relying on institutional offices for students with disabilities to recruit participants for studies on student experiences regarding mental health disorders may contribute to the invisibility of this population, as well as potentially conflating the experience of these students with others who experience depression in addition to living with multiple disabilities and related challenges.

Although the relationship with university staff was not an invariable constituent of women’s experience of depression, it was reflected in women’s agency to negotiate support. Particularly in graduate studies where students had a relationship with their instructors, accommodations for the experience of depression were negotiated directly according to individual needs and often without having to disclose a diagnosis. Overall, the graduate students with depression found their instructors supportive. Women in undergraduate studies, depending on the program, did not seem to form close enough relationships with course staff to reach out or negotiate course requirements to assist them in managing depression. Depression temporarily disrupted the students’ ability to organize their lives and contributed to the experience of role overload. Well-organized courses that included detailed schedules allowed the women to integrate their academic schedules with the scheduling of work and family responsibilities. Course design needs to be clear, and un-paced courses need to offer detailed examples of scheduling for completion of readings and assignments. Courses that included these design elements were appreciated by both the undergraduate and the graduate students.

Role overload has a stronger relationship to women’s mental health than any other sociodemographic variable (Glynn et al., 2009). Research by Glynn et al. (2009) demonstrated that poorer mental health was significantly associated with perception of role overload and supported the importance of “measuring women’s experience of their multiple roles rather than focusing on single roles” (p. 217). Women in the current study clearly experienced role overload during their online studies, which contributed to their experience of depression and, sometimes, triggered a depressive episode. Most of the women expected to work and study full time, and many were also parenting. They discovered that these were unrealistic expectations and, eventually, many reduced their course load or work hours to cope with the overload. Kramarae’s (2001) seminal study of women and distance learning found that role overload impacted women’s experience of post-secondary online learning as well as their mental health. Their experiences suggest that it is important for institutions to offer, advertise, and normalize multiple paths to academic success in addition to full-time studies. Institutions may also need to consider the gendered nature of role overload in their provision and promotion of mental health education and supports.

Most of the women were not aware of the supports for students with disabilities and of the mental health supports offered by their university. Although they all accessed mental health and medical supports in their own communities, accommodations and free course extensions would have been available to the women through the institution. Online institutions need to consider the visibility of messages regarding mental health and mental health supports on their course websites as well as ensuring that instructors can appropriately communicate the importance and normalcy of accessing supports.

Finding ways of tracking students who live with mental disorders, and who may not register with services for students with disabilities, is encouraged. As Canadian post-secondary institutions increase their participation in large North American survey studies investigating post-secondary populations, including the National Collegiate Health Assessment (American College Health Association, 2019), resulting data could be of use in improving program supports for students living with mental disorders. Exit information on why students leave their programs, including mental health concerns, would provide needed information for educational institutions that desire to improve their programs. Institutions might also consider the potential consequences of advertising that students can “do it all” by choosing distance education.

This study highlighted the experience of women who persevered in their online studies while living with depression. Unknown is what happens to students who are unable to navigate this experience. How many students leave their studies because of depression or other mental health disorders? What pedagogical, program, and course design decisions might best support students including those living with mental health disorders? For example, the cognitive impact of depression might be somewhat mitigated by paying attention to evidence-based approaches, including multimedia learning principles regarding the reduction of extraneous processing and reducing complexity (Abrami et al., 2011). Future research might also look at how and why students view their experience of having a mental health disorder as having a disability or not. The importance of studying student experience in a wider societal context, beyond the online experience, may assist in the development of online experiences that encourage greater student support and, as a result, retention. Expanding on this study’s recommendations, future studies might focus on the experience of depression of men and women while learning online, as well as students’ experience of other mental disorders including anxiety. These would add to our knowledge and development of supportive environments for students.

Limitations are related to the use of specific methodologies (Simon & Goes, 2013). Phenomenological studies include the possibility of researcher bias. To address this limitation, a descriptive phenomenology method was chosen, which included the assumption of the signalling phenomenological attitude for data analysis and reflexive journaling throughout the research process. The study’s focus on in-depth analysis of individual accounts of experience, along with the small sample size, while congruent with phenomenological methodology and the aims of this study, makes generalizability to larger populations impossible. The inclusion of participants from a single university further limits comparison to the experience of students in other post-secondary settings. Also, as volunteers, participants were self-selected, which excludes the experience of women who did not volunteer for the study. Lastly, ethical research avoids harm to research participants including harm to members of vulnerable populations, which include participants who suffer from mental disorders. Therefore, the study included only women who had recovered from depression during their online studies. As a result, participants relied on the recollection of their past experiences of depression rather than current experience.

This descriptive phenomenological study of women as online learners who have experienced and recovered from depression while learning online was designed to provide a rich and in-depth view of the experience. The experiences of the women in this study may be used to improve the experience of online learning for other students who experience depression, including, but not limited to, program and course design, academic paths to success, and supports for students. Researchers are encouraged to compare this study with previous studies on post-secondary students with depression and other mental disorders. This study may help to make members of this mostly invisible population visible and their stories heard. In the spirit of visibility, the concluding comments are drawn from Justine’s story of recovery from depression during her online studies.

Justine credited her online program as having played a significant role in her recovery from depression and the monitoring of depressive symptoms. Although much of the coursework in her graduate program could be considered self-taught, there were ongoing expectations of frequent postings to online discussion forums (a minimum of three per week) and, often, additional smaller postings. These online discussions with peers drew Justine out. As she posted more, and was drawn into discussion forums, her posts went from being very formal, with references, to sharing ideas with her peers. Eventually, Justine also had phone conversations with peers. In the last semester of her program, between work, parenting, and school, she felt herself slipping back into depression. Justine recognized a familiar pattern of getting behind in her postings, an increase in fatigue, reduced functioning at work, and less socializing. She took a week and a half off for self-care and to organize herself. This was enough to get her back on track and to avoid another depressive episode. Justine described her performance and participation in her online studies as her “canary in the coal mine” for monitoring depression and online interaction with peers as “the first little hand that pulled [her] out of it.”

Abrami, P., Bernard, R., Bures, E., Borokhovski, E., & Tamim, R. (2011). Interaction in distance education and online learning: Using evidence and theory to improve practice. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 23, 82–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-011-9043-x

Afifi, M. (2007). Gender differences in mental health. Singapore Medical Journal, 48(5), 385–391. http://smj.sma.org.sg/4805/4805ra1.pdf

Allan, J., & Dixon, A. (2009). Older women’s experiences of depression: A hermeneutic phenomenological study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16(10), 865–873. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01465.x

American College Health Association. (2019). ACHA-NCHAII: Reference group executive summary. https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-II_SPRING_2019_US_REFERENCE_GROUP_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Angst, J., Gamma, A., Gastpar, M., Lépine, J.-P., Mendlewicz, J., & Tylee, A. (2002). Gender differences in depression: Epidemiological findings from the European DEPRES I and II studies. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 252, 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-002-0381-6

Broome, R. (2011). Descriptive phenomenological psychological method: An example of a methodology section from doctoral dissertation. Utah Valley University. https://works.bepress.com/rodger_broome/9/"

Dalgard, O., Dowrick, C., Lehtinen, V., Vasquez-Barquero, J., Casey, P., Wilkinson, G., Ayuso-Mateos, J., Page., H., Dunn, G., & The ODIN Group. (2006). Negative life events, social support and gender difference in depression: A multinational community survey with data from the ODIN study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41, 444–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-006-0051-5

Dukas, C., & Kruger, L. (201). A feminist phenomenological description of depression in low-income South African women. International Journal of Women’s Health and Wellness, 2(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.23937/2474-1353/1510014

Duxbury, L., Stevenson, M., & Higgins, C. (2018). Too much to do, too little time: Role overload and stress in a multi-role environment. International Journal of Stress Management, 25(3), 250–266. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000062

Finlay, L. (2008). A dance between the reduction and reflexivity: Explicating the “phenomenological psychological attitude.” Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 39(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1163/156916208X311601

Finlay, L. (2009). Exploring lived experience: Principles and practice of phenomenological research. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 16(9), 474–481. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2009.16.9.43765

Giorgi, A. (2007). Concerning the phenomenological methods of Husserl and Heidegger and their application in psychology. Collection du Cirp, 1, 63–78. https://www.cirp.uqam.ca/documents%20pdf/Collection%20vol.%201/5.Giorgi.pdf

Giorgi, A. (2009). The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology: A modified Husserlian approach. Duquesne University Press.

Glynn K., Maclean, H., Forte, T., & Cohen, M. (2009). The association between role overload and women’s mental health. Journal of Women’s Health, 18(2), 217–223.

Kessler, R. (2003). Epidemiology of women and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 74(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00426-3

Kirsh, B., Friedland, J., Cho, S., Gopalasuntharanathan, N., Orfus, S., Salkovitch, M., Snider, K., & Webber, C. (2016). Experiences of university students living with mental health problems: Interrelations between the self, the social, and the school. Work, 53(2), 325–335. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-152153

Kramarae, C. (2001). The third shift: Women learning online. American Association of University Women Educational Foundation.

Krasowski, S. (2018). Canadian National College Health Assessment survey: Report on responses from AU students. Athabasca University.

Li, C.-C., Shu, B.-C., Wang, Y.-M., & Li, S.-M. (2017). The lived experience of midlife women with major depression. Journal of Nursing Research, 25(4), 262–267. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnr.0000000000000159

McIsaac, P. L. (2021). Chiming in: Social presence in an international multi-site blended learning course [Doctoral dissertation, Athabasca University]. DTheses. http://hdl.handle.net/10791/348

McManus, D., Dryer, R., & Henning, M. (2017). Barriers to learning online experienced by students with a mental health disability. Distance Education, 38(3), 336–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2017.1369348

Moisey, S. (2004). Students with disabilities in distance education: Characteristics, course enrollment and completion, and support services. Journal of Distance Education, 19(1), 73–91. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/102754/"

Pearson, C., Janz, T., & Ali, J. (2013). Mental and substance use disorders in Canada. Statistics Canada, Minister of Industry. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/82-624-x/2013001/article/11855-eng.pdf?st=DfOkhJG8

Piccinelli, M., & Wilkinson, G. (2000). Gender differences in depression: Critical review. British Journal of Psychiatry, 177(6), 486–492. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.177.6.486

Røseth, I, Binder, P.-E., & Malt, U. (2013). Engulfed by an alienated and threatening emotional body: The essential meaning structure of depression in women. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 44(2), 153–178. https://doi.org/10.1163/15691624-12341254

Shakalis, W. (2014). A comparative analysis of the transcendental phenomenological reduction as explicated in Husserl’s Ideas Book One, with Amedeo Giorgi’s ‘scientific phenomenology.’ School of Library and Information Science, Simmons College. https://www.academia.edu/7947737/A_comparative_analysis_of_the_transcendental_phenomenological_reduction_as_explicated_in_Husserl_s_Ideas_Book_One_with_Amedeo_Giorgi_s_scientific_phenomenology_

Simon, M., & Goes, J. (2013). Dissertation and scholarly research: Recipes for success. Dissertation Success, LLC. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.5089.0960

Weiner, E. (1999). The meaning of education for university students with a psychiatric disability: A grounded theory analysis. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 22(4), 403–409. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095209

World Health Organization. (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/depression-global-health-estimates

York, C., & Richardson, J. (2012). Interpersonal interaction in online learning: Experienced online instructors’ perceptions of influencing factors. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 16(4), 83–98. https://10.24059/olj.v16i4.229

Zimmerman, B., & Cleary, T. (2006). Adolescents’ development of personal agency. In F. Pajres & T. Urdan (Eds.), Adolescence and education (Vol. 5): Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 45–69). Information Age Publishing.

Tracy Orr is a social work instructor at Portage College in Lac La Biche, Alberta, Canada. She received a Master of Social Work degree from Wilfrid Laurier University and Doctorate in Distance Education from Athabasca University. Dr. Orr teaches in a variety of blended learning environments. She is interested in the intersection of online learning and student mental health, rural and northern student experience, and blended learning solutions for social work continuing education and degree completion.